Most honest postmortems of Trump’s election are by Democrats focusing on what they missed. Usually, they are either narrow exercises in vote counting or more holistic attempts to understand Trump voters. In the latter group are Joan Williams’s White Working Class and Ken Stern’s Republican Like Me.

The common thread in these is discovery, a dawning realization that there are people out there with legitimate, even compelling, reasons to vote for Trump.  Republicans, on the other hand, haven’t engaged much in postmortems. They have engaged in recriminations, or a facile triumphalism, but few seem to have analyzed Trump’s election in a focused, professional, way. The Great Revolt fills that gap.

Republicans, on the other hand, haven’t engaged much in postmortems. They have engaged in recriminations, or a facile triumphalism, but few seem to have analyzed Trump’s election in a focused, professional, way. The Great Revolt fills that gap.

There’s nothing truly startling in this book, but it’s still interesting. The authors’ core point is that Trump’s election is not a fluke; whatever his faults may be, they do not outweigh his good points in the view of a wide variety of voters, including groups of people who, on the surface, have little in common with each other and seem like they shouldn’t like Trump.

Moreover, most of these people were previously reliably Democratic voters. To analyze this and to demonstrate their thesis, Salena Zito (a journalist) and Brad Todd (a Republican pollster and consultant) conducted detailed opinion surveys, and then let people talk for themselves to supplement and exemplify the aggregate results, using individuals, meant as archetypes, from ten very different counties in five different swing states (Pennsylvania, Ohio, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Michigan).

Zito and Todd break the Trump voters they examine into seven groups, each with specific demographic characteristics. “Red-Blooded and Blue-Collared” are those who “had worked a blue-collar, hourly wage, or physical labor job after the age of twenty-one, and had experienced a job loss in the last seven years either personally or in their immediate families.” “Girl Gun Power” are women under forty-five who owns guns for self-defense. “Rough Rebounders” are those who have overcome significant obstacles (and thus resonate with Trump’s story). “Rotary Reliables” are Chamber of Commerce Republicans—but with a twist, that they are from smaller towns, and therefore are surrounded by, and socialize with, conservatives and the working class, thus appreciating their concerns, similar to the way that such Republicans in bigger towns and cities are surrounded by liberals and therefore function as liberals.

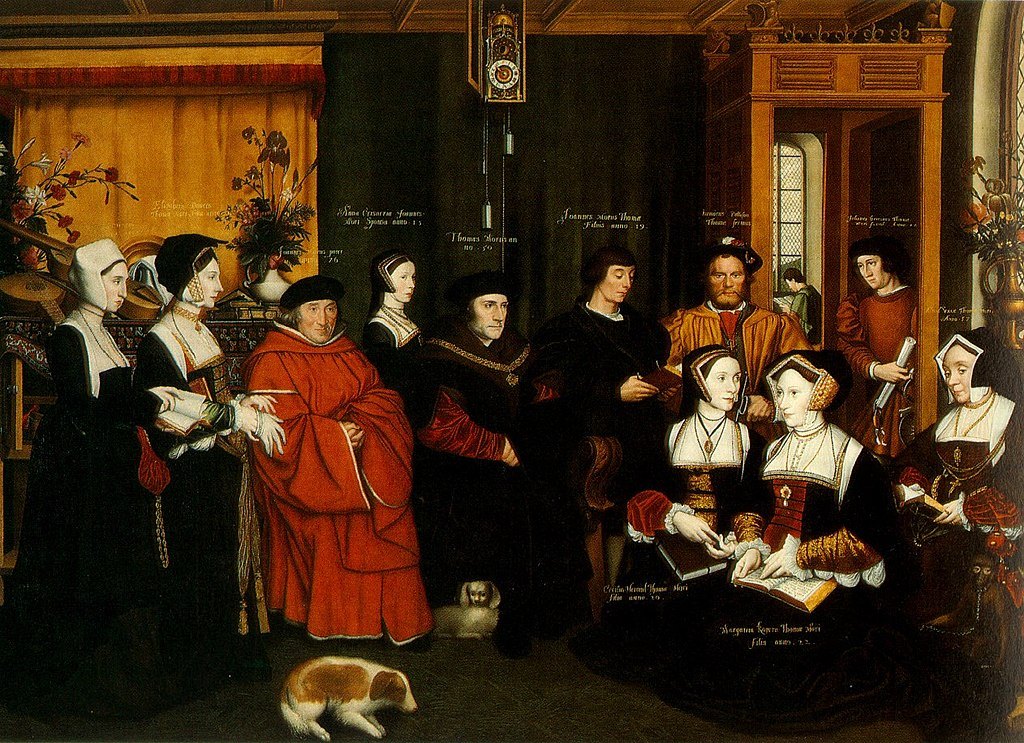

That is to say, these Rotary Reliables are diverse and inclusive, more so than their Republican counterparts in the cities. “King Cyrus Christians” are religious believers who are willing to overlook Trump’s dissolute personal life, as the Jews took advantage of the heathen Cyrus the Great’s release of the Jews from Babylonian captivity.

(While I don’t understand why some evangelicals, like Franklin Graham, fawn over Trump, other than to be close to power, it is perfectly understandable, given that Hillary was the Right Hand of Satan, that devout Christians would vote for Trump, since, to coin a phrase, “If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice”).

“Silent Suburban Moms” are upper-middle class women somewhat turned off by Trump’s boorishness, and fearful of the hatred directed at them if they openly support Trump, but who support Trump nonetheless. Collectively, I am not sure that these really constitute the “populist coalition” of the subtitle, but they have more in common than just supporting Trump, and more in common than a casual observer might think.

In particular, in all these groups the same three specific issues keep cropping up (along with some other issues that are more or less important to specific groups). Given the significant differences across these sets of people, this consistency is surprising.

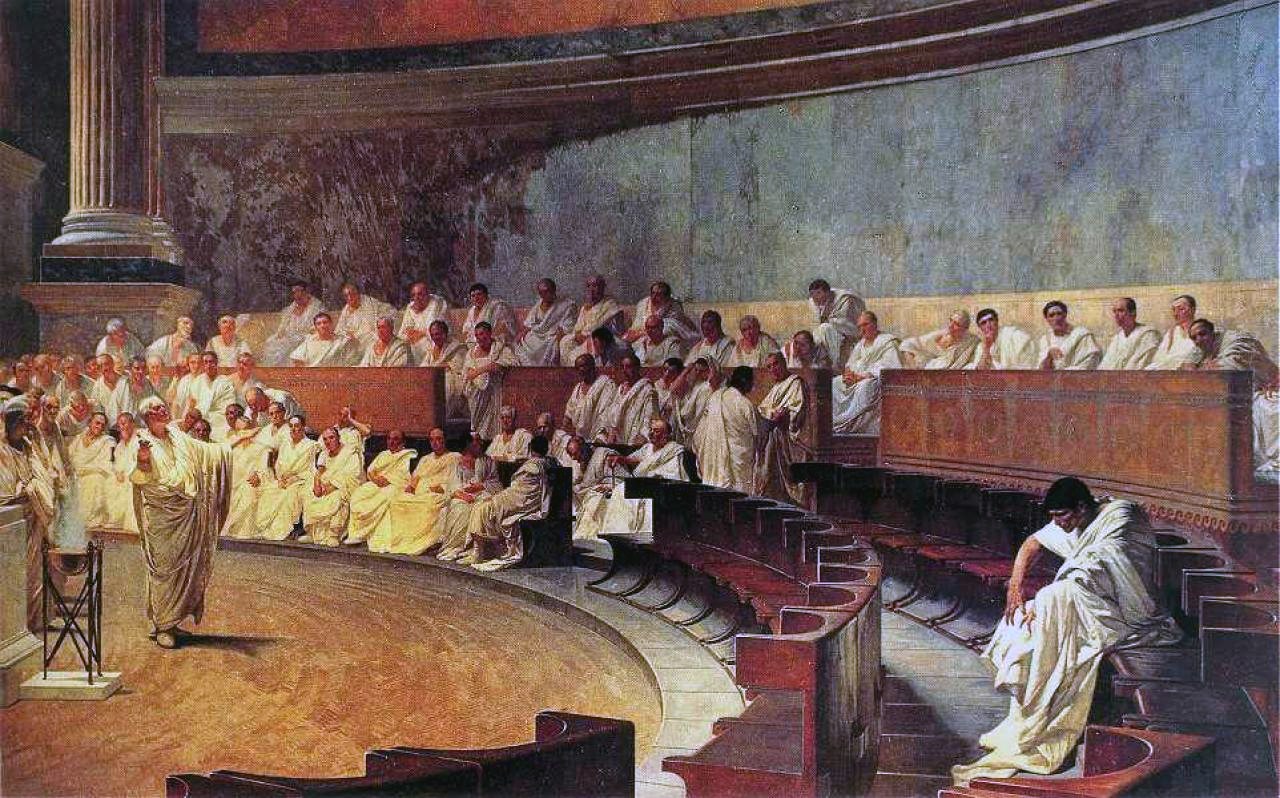

These three issues are who controls the Supreme Court, gun rights, and, most interestingly, the habit Obama had of apologizing, purportedly on behalf of the United States. (As all such studies find, and utterly contrary to the view of progressives, racial issues almost never crop up, and illegal immigrants less than you would expect.) The first two have a straightforward analysis—Democrats have for decades tried to evade democratic rule by using the Supreme Court as a leftist super-legislature, and Republican voters are well aware of that.

Gun rights require even less discussion—in fact, in the past few months, driven mad by anti-Trump frenzy, prominent Democrats have begun openly declaring what they always lied about in the past, but which has always been true—that yes, they want to take away every single gun normal Americans own.

But I would not have thought the constant apologizing was so important, and so disturbing, to voters. These people are not wrong about Obama’s habit of apologizing.

He began his term by apologizing to the entire Muslim world and then in nearly every (or perhaps every) foreign speech he made ensured that his speechwriters worked in some form of abasement for supposed past misdeeds of the United States. Usually those misdeeds were left a little vague, such that the listeners were expected to fill in the specifics of their own particular grievance, so as to maximize the breadth and perceived impact of the apology. The substance or rationale of these apologies, though, doesn’t really interest me. Rather, I am curious why the voters were so upset.

It seems to me that apologies can vary on two basic axes—by whom, and to whom. On the former axis, they can be made by the wrongdoer (Class A), or on his behalf by a legitimate representative (Class A’). Or they can be made by a successor in interest, who did not participate in the original wrong but has a material link to that person (Class B).

On the latter axis, apologies can be made to people who are wronged (Class 1), or to their successors in interest (Class 2). (I put into Class 2 also those who have only suffered a lesser, derivative wrong, but those could be a third class, if you wanted to complicate the analysis.)

Most people across the political spectrum would agree, I think, that apologies by Class A or Class A’ to Class 1 are unexceptional and some combination of desirable and necessary (or rather, they are unexceptional in the West, infused with Christian values—in a place like China, very different rules apply, which we will ignore here). Apologies by Class A to Class 2 seem less required and desirable.

This is because the person wronged is the person who is “owed” the apology and is able to forgive—someone who has not suffered a wrong has neither the same right nor ability to forgive, and by the same token, is less deserving of an apology.

Even less required or desirable is an apology from Class B to Class 1, since personal responsibility only attaches to a wrongdoer. Least appropriate of all is an apology from Class B to Class 2, where all parties involved have no actual connection to the wrong at issue.

I think what rubbed the people in this book the wrong way is that all of Obama’s apologies were in that last and least deserving category (or, arguably, were in a fifth category, of a supposed Class B person apologizing for something done earlier that was not a wrong at all).

Obama was not a Class A’ representative, although he may have viewed himself that way, because he was not representing any actual wrongdoers, either because the actual wrongdoers are dead, or because no wrong was committed at all. And naturally, Obama never apologized for something he did—only for wrongs done by elements of the United States government, or elements of our ruling class (and sometimes even for elements of other governments and ruling classes).

Even if we assume that these wrongs were actual wrongs, and were as bad as Obama said, it is evident from what they say that the voters profiled in this book were viscerally outraged both by the stupidity of any “Class B to Class 2” apology, which necessarily humiliates the United States for no good reason.

They also were angered by the knowledge that Obama in no way blamed the recipients of the apologies, much less himself, or his cronies, or progressives, or any of their predecessors in interest, for anything. Instead, all blame was to attach to a subset of current day Americans, who had done nothing at all to anybody—namely, the voters profiled in this book.

Hillary Clinton was more explicit on this point, but nobody was fooled that Obama didn’t think the same way—he was just smoother. So maybe that this theme keeps cropping up as an element of Trump’s support isn’t all that surprising after all.

One claim by the authors rings false, though. They say that Facebook, not the New York Times, “now drives the national conversation with the horsepower of its search traffic and algorithms.”

But it is the NYT, with a junior role played by a handful of media outlets equally totally under the control of leftists, that sets both what is considered to be news and what the agenda behind that selection is. Anything not fitting the agenda is not considered to be news among the ruling classes and therefore is ignored and functionally suppressed; “it’s just Fox News.”

This indirect censorship is extremely powerful, and Facebook does not overcome it, even if it used to allow alternative new sources to rise to the top of its news feed. And, since the election, Facebook has gotten in line, changing its news feed from showing what people are actually choosing to view, to forcing down on people only approved outlets (that is, the NYT and its cronies), along with using leftist “fact checkers” such as Snopes and Politifact as cover for direct censorship.

Moreover, they (and Twitter, etc.) are moving, just in time for the 2018 election, to further censor “hate speech,” defined as conservative speech. So, between a combination of Facebook not setting the agenda itself, but rather taking direction from the Left, and actively cooperating in driving the news coverage to favor the Left, nothing has changed at all.

In fact, contrary to conservatives’ hopes of the early 2000s, the NYT has much more power to set what is news and what is the agenda, since almost all alternative media enterprises of any public standing and reputation, that did not feel obliged to always toe the line, are out of business or a shadow of their former selves.

That said, again and again the people in this book say that they have completely tuned out of the news, because it is so obviously unhinged leftist propaganda. This suggests that the impact of the NYT’s death grip on curating the news may be less than the Left hopes, or the Right fears.

Tied to this is another fact that comes up time and again—many of the interviewees self-censor on social media, afraid of the hatred directed at them by their “friends” for the political views, a problem never faced by their political opposites, who preen themselves on their alignment with the selected news they are shown and regard pouring malice on those who disagree with leftist views as a holy cause.

But when one group grows silent, they do not thereby agree more, and they are more likely just becoming submarine voters, which is the authors’ point. True, some voters may still be soaking in the propaganda, unwilling or unable to cut the cancer out of their lives, but my guess is that nearly all have tuned out the vast majority of it.

I certainly have, even though I subscribe to the NYT—for years, now decades, I used to just ignore the editorial pages, but now I ignore all articles that are not completely unrelated to politics (an ever-shrinking group), since any article even tangentially involving politics is indistinguishable from the op-ed page.

So what does this mean for the immediate future? Nearly all of the counties profiled voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012, and then swung hard to Trump in 2016. The authors note that this is an unstable situation—the voters could easily swing back.

In many instances, their voting for Trump was a combination of Trump’s stands and an explicit feeling that the Democrats left them, not the reverse. (We are constantly showered with claims by supposed former Republicans that their party left them, but the media never suggests the same process is equally possible for Democrats.)

If the Republicans nominated some Chamber of Commerce blob like Jeb Bush, or even a zombie Reaganite like Ted Cruz, and the Democrats nominated someone not a shrill, hateful, decaying crone or an elderly Communist, or dialed back their obsessive focus on the politics of identity and grievance in favor of acknowledging the concerns of the people interviewed in this book, I bet that’s exactly what would happen.

Still, Zito and Todd believe that the more likely outcome is that the Trump coalition holds together, and that neither party has fully grasped this likelihood. (On a related note, the reason that progressives want to get rid of the electoral college is precisely to avoid this outcome, by making it unnecessary for national politicians to capture any votes outside urban areas).

Naturally, this book has been ignored by the liberal media, which suggests a continuing failure to grasp this obstacle to leftist dominance.

But the core social problems that make these counties suffer are not going away anytime soon. Unemployment might be addressed by a different economic policy, but that is unlikely to happen with the levers of economic power being held by globalists, and even if we changed our policies, it is not likely that the 1950s will come again.

And this is true not just because it’s impossible to go back—in addition, the social fabric of these counties is utterly destroyed, although the voters don’t seem to want to realize that. The biggest single problem is opiates, followed by a breakdown in families and the same atomization of society found everywhere.

Even if $30/hour jobs returned, these problems would persist. This suggests that to the extent voters hope Trump will make a dent in their social problems, they are likely to be disappointed. Yes, he will protect their guns and their religious liberty; he will issue no apologies; and he will stick his finger in the eye of the liberal media.

But is that enough? Probably to keep their votes for a while. In the end, the question is whether substantive change is required for these voters to be happy, or merely fighting on their behalf. We’ll find out soon enough.

Charles is a business owner and operator, in manufacturing, and a recovering big firm M&A lawyer. He runs the blog, The Worthy House.

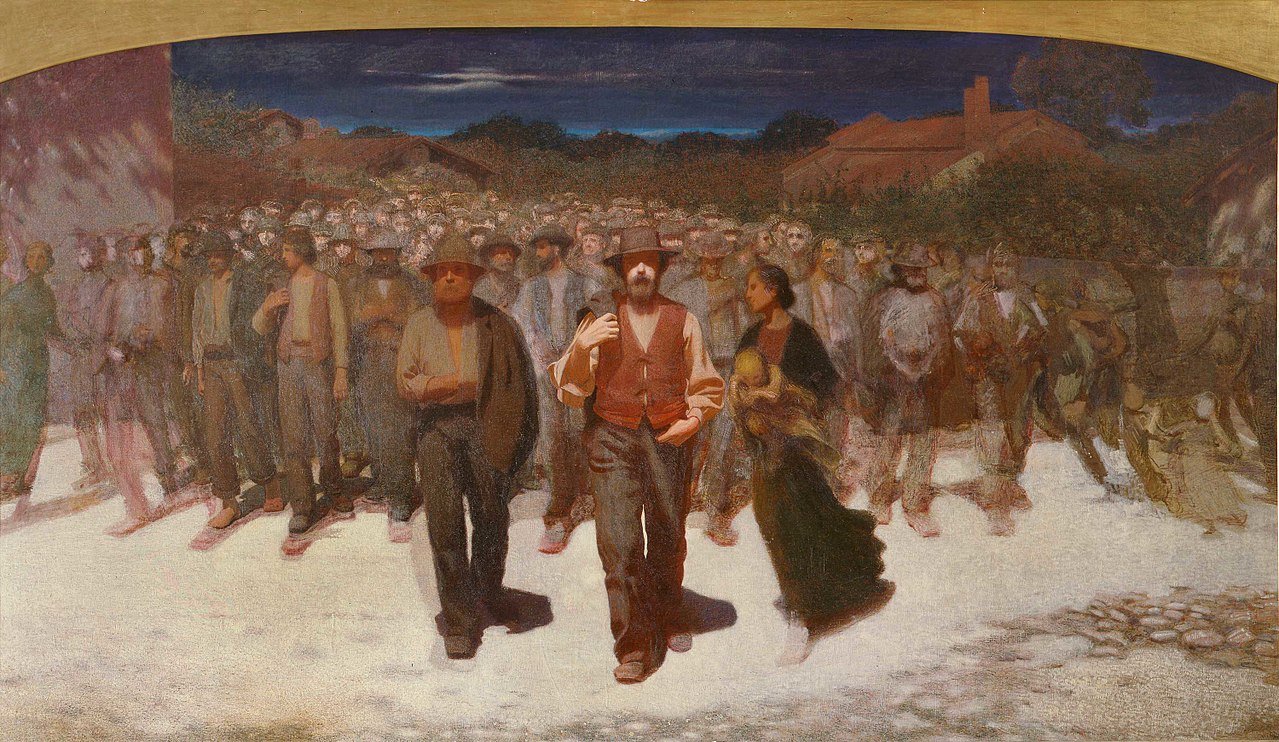

The photo shows, “La fiumana [Stream of People]” by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, painted ca. 1895-1896.