Exhaustively documented, and in some ways just exhausting, though at the same time exhilarating, Brad Gregory’s The Unintended Reformation is a towering achievement. It synthesizes centuries of history and multiple avenues of thought to analyze how we arrived at certain negative aspects of modernity.

thought to analyze how we arrived at certain negative aspects of modernity.

Gregory’s claim is that we got here as the result of the unintended consequences of choices made in response to “major, perceived human problems.” Those choices were, initially, the Reformation’s religious choices, which ran counter to the entire worldview of medieval Christianity.

But the Reformation did not solve the problems—it made them worse, in a declining spiral, accelerated and exacerbated by subsequent secularization, itself partially the result of the Reformation. The result is a world in which the ability of humans to find meaning in their lives has been crippled, rather than enhanced. We would, implicitly, be better off with something more like the High Medieval synthesis destroyed by Martin Luther.

This is a reactionary book, of course, even if that is not the author’s intent. Any book that, in effect, revolves around the idea that the medieval European tag team of church and state, each in its own sphere, together produced a better society than the one we have today, a superior “institutionalized worldview,” is necessarily reactionary.

Étienne Gilson sighs contentedly in his grave; Jacques Maritain smiles; Carl Schmitt chuckles grimly. Of course, reaction as a political program, as I have said before, is not a return to some past Golden Age, or, more drily phrased, to the status quo ante. Such a definition is meant to be both pejorative and to absolve progressives of any need to respond to reactionary thought. Rather, reactionary political thought is any thought directed at what should be done now, if and to the extent such thought relies or is based on reference to the past as a positive guide.

The most critical element of reactionary thought is, therefore, that it does not regard the past as superseded. All supersessionist narratives are automatically rejected as incoherent. There is no arc of history; it has no right side.

History embodies good and evil, justice and injustice, truth and falsehood, and the task of the political thinker of the Now is to take these strands and make of them a world in which fallen human beings can flourish. Much of this book is an explicit rejection of “supersessionist history,” the Whig or progressive idea that the world today is the way it is because that is the way it was destined to be.

The past is not even past, and human life is, contra writers like Steven Pinker and Jonah Goldberg, not explained and justified by the Enlightenment. It is explained by the choices we have made; some of those choices were bad, and they should be unspooled, if possible, and new, better choices made.

In fact, I hold that a necessary element of a reactionary political program is viewing the world with, if not new eyes, from fresh perspectives, those lacking today as the sun sets on the Enlightenment experiment. More and more, I think of Enlightenment thought as the picture of Dorian Gray, whose flaws were concealed until they weren’t. Or, perhaps, the Enlightenment is one of those rockets under which the fire flares, and it majestically rises from its launchpad, a study in power and might—but something is wrong; it hesitates; it halts; it falls backward, downward to destruction.

Reaction by definition finds the present wanting, and the present projected forward even more wanting, which is a view that necessarily conflicts with the unexamined common assumptions of our time. Thus, Gregory’s book is, if Reaction is radical, a very radical work, though it doesn’t feel like it while you’re reading it, and Gregory might disagree.

That’s a lot of talk about myself in a review of someone else’s book. I offer those initial thoughts because I am now formally turning to my study of Reaction, in preparation for completing and offering my own book-length thoughts on Reaction as a viable political program. I have already begun this project, in a stop-start manner, with analysis of Mark Lilla’s book on reactionary thought, The Shipwrecked Mind, as well as in some other reviews, in particular of Adrian Goldsworthy’s Augustus and Victor Sebestyen’s Lenin.

In my turn to reading on Reaction, I intend to focus not on formally reactionary pamphlets or roadmaps (although those, and much else, will appear), but on a wide variety of books that shed light at an angle, as it were, on political philosophy as it exists in the early twenty-first-century West. We will spend much time traveling back in time, and maybe a little traveling forward in time (I do like science fiction, after all).

As with all my reviews, though, I’m doing this for me, not for you. I intend this to be the homework for, and assist me in writing, my very own work of political thought, which I plan to be an actual roadmap for political Reaction—for, after all, it is easy to analyze, and easier to criticize, but hard to create a positive and coherent program.

So, to Brad Gregory’s book. This book took me forever to read. It is only four hundred pages, but it has two hundred more pages of footnotes, most of which I studied and pondered, and for a non-trivial amount of which I examined the works to which Gregory refers, something Amazon and an unlimited budget for buying books permits.

But such depth does not mean the book is bad; it is quite good, and it has gotten a lot of attention, though probably more attention than actual readers, I suspect. It is now five hundred years since the Reformation, and Gregory does not think it was a good five hundred years. The Reformation ruined the medieval institutional synthesis, which, while far from perfect, had many virtues missing today.

And the Reformation necessarily and directly led to the worst aspects of modernity, mediated by the aggressive secularism of the Enlightenment. First, to atomization and polarization. Second, to unbridled consumerism, to the “goods culture” (as opposed to the “culture of the good”), with no “acquisitive ceiling” and with the loss of the concept of excess, which leads to spiritual anomie and other harms such as environmental catastrophe (including climate change). Third, and perhaps most importantly, if most abstractly, to an inability to reconcile competing “truth claims,” and in fact the rejection of the entire category of truth, leading to “hyperpluralism,” excessive emancipation and, implicitly, to the near destruction of the entire Christian project, although Gregory does not directly predict that outcome. Explaining an entire culture and its changes over five hundred years is no small task.

Gregory therefore breaks his analysis into six separate narratives, while cautioning that they are not, and cannot be, separate in real life, and are to act in conjunction in his book. “As a whole the book thus constitutes an explanation about the makings of modernity as both a multifaceted rejection and a variegated appropriation of different elements of medieval Christianity. . . .The six strands in the analysis focus respectively on the relationship among religion, science, and metaphysics; the basis for truth claims related to human values and meaning; the institutional locus of the public exercise of power; moral discourse and moral behavior; human desires and capitalism; and the relationship between higher education and assumptions about knowledge.”

You begin to see what I mean by saying this book is exhausting.

Gregory’s first thread, on “religion, science, and metaphysics,” revolves around a common complaint of modern conservative thinkers, that late medieval Schoolmen, most notably William of Ockham, endorsed nominalism and thereby laid the groundwork for modern relativism and secularism. But this is secondary to Gregory’s main focus, on thought preceding but tied to nominalism, centering on “univocity.”

This is the change from holding, with Aquinas, that God has nothing in common with humans, but can only be understood in His characteristics by analogy, to holding that God shares with us the characteristic of “being” or “existence,” even if in a qualitatively different way than humans. (By chance I am also currently reading David Bentley Hart’s outstanding The Experience of God, which extensively covers the same topic).

In Gregory’s reading, this change, led by John Duns Scotus, leads to the effective lowering of God, whom it becomes easy to view as one being among others, even if superior in every way. God becomes a mere demiurge, or at most the God of Deism, not the transcendental ground of all reality.

The basis for this move to univocity was that otherwise it was deemed impossible to reason about God, a desired end of the Scholastics. Analogy was held to be an unsatisfactory method of analysis, although until that date it was the universal method in Christianity.

What the Schoolmen did not see was that if univocity is true, yet no direct evidence for God is seen in the natural world, it becomes easy to exclude God when reasoning about any topic at all, since the logical conclusion under univocity is that He does not exist, or if He does, it is impossible to prove. Science and faith thus began to be seen as logical opposites, though that is certainly not what the original proponents of univocity intended, nor is it a rational stance.

The Reformation exacerbated this problem, with many reformers, especially in the Zwinglian dispensations, rejecting sacramentality, with such rejection being fundamentally a univocal approach, a disenchantment of God’s role in the universe. And as the Scientific Revolution proceeded (driven by other aspects of European Christianity, but that is another story), and Ockham’s Razor used as the basis for approaching theories of the natural world, it became modish, therefore, to hold that God was disproven, or logically unproven, or at least unnecessary to reckon with.

Under the traditional understanding of God’s nature, nothing could be farther from the truth. And in the new analysis, God was not in fact disproven, nor were any of the traditional and highly sophisticated analyses of His nature undercut—rather, a category error swallowed the whole analysis.

But increasingly, and to this day, proponents of naturalistic philosophy acted as if God were disproven and traditional analyses obviated—in which acting they were helped by the intellectual weakness of their Christian opponents, increasingly fragmented and untutored in the realization that they had themselves absorbed univocal premises.

But given that this is how intellectual fashion developed, the effect was to exclude God from an ever-widening philosophical sphere. Moreover, the fragmentation of Christian thought and unity produced by the Reformation further eroded any possible influence of Christian belief, since there were so many competing, and inherently incompatible, views on critical matters. Easier to ignore and dismiss them all.

Gregory’s main point is that “truth claims” are different if the claimant believes in God (really believes, not pseudo-believes, like followers of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism). If God has no relevance, moreover, emancipation can plausibly become a more elevated goal. And, importantly, religion becomes mere, and burdened by, sentiment—hence, feelings and emotivism, which, in a feedback loop, leads to the conclusion that science and faith are opposites.

Moreover, the disenchantment of the world leads to its instrumental use; the road leads directly from Francis Bacon to mountaintop removal, the Great Pacific garbage patch, and global warming.

Gregory’s second thread, which therefore follows from the conclusion of the first, “the basis for truth claims related to human values and meaning,” is really the hinge of the entire book. If such truth claims didn’t matter, there would be no point in decrying the inability to find a coherent basis for them.

The point here is simple, though fleshed out in detail. It is that truth claims matter, and that the Reformation, a justified, or at least understandable, response to the massive moral failings of fifteenth-century Christians, instead of making the basis for those truth claims more robust, destroyed it by making every man his own priest. Truth claims are, in essence, “Life Questions”—what should we believe, and why?

What is meaningful in life? How should I lead life? Until the modern era, religion, Christianity in the West, uniformly provided the answers, or at least the starting points and midpoints for answers, to such questions. Not that the answers were entirely uniform before the Reformation—not only personal idiosyncrasy, but the wide range of diverse answers within Christendom made that untrue. “The late medieval church was a large playground, but one enclosed by forbidding fences. . . .”

The Reformation principle of sola scriptura was meant to hack off the supposed encrustations of the Roman Church, not to allow every person to form his own opinion about all matters of doctrine, but once the principle was admitted, there was, and never could be, any logical stopping point.

Thus, the Reformation produced an exponential growth in competing truth claims, made worse when biblical interpretation was joined by claims of interpretation guided by the Holy Spirit, as those made by Quakers. The end result, after centuries, is incoherence and religion as Philip Rieff’s “therapeutic culture,” religion as a vague feeling of being good and feeling good, since there is no firm ground—what Gregory repeatedly calls “the Kingdom of Whatever.”

The trend toward this end, combined with the Wars of Religion, supported the Pyrrhonian skepticism that emerged at the beginning of the Enlightenment, and Gregory covers Descartes, Hume, Montaigne, and many others in this light. His point, though, is not to endorse them, but to note that all of these, and many other more modern philosophers, are equally unable to agree on answers to the Life Questions, so incoherence is not a function of religion; it is equally applicable to analysis sola ratio. Whose fault? The Reformation’s.

Gregory’s third element in his conjunction is “the institutional locus of the public exercise of power.” From the perspective of secular rulers, ever more fractalization of truth claims was intolerable (especially after the Peasants’ War), so they chose winners and enforced their claims in each ruler’s domain.

As a result, we tend to perceive a less wide range of doctrine in Protestantism than actually existed, since the “magisterial” churches (basically Lutheranism and Calvinism) became important due to their adoption and enforcement by the state, and the “radical” churches became fragmented and of much less public importance, except in a few notable or dramatic instances, such as the Anabaptists in Münster.

Even today, the result is that “our respective sovereign states dictate what individuals and institutions can and cannot do in exercising religious faith” (a tension we saw this week in the Supreme Court’s Masterpiece Cakeshop decision).

To get to discussing this post-Reformation problem, Gregory reviews the tangled Western history of church and state, both in its historical highlights and in the practical effects, including the regular failures of the church, and Christians, to live up to Christ’s commands.

The effect of the post-Reformation increase in state power over the role of churches has been that “churches in general would [now] exert only as much public power and authority as they were permitted,” which used to be a lot, but which, “in the early twenty-first century, when sovereign states rule together with the market, it is almost none.”

Again, to Gregory, this is a bug, not a feature. Concurrently, state power itself rose, and religion became a prime driver of war, ultimately resulting in the not-illogical conclusion, beginning with the Dutch, that we would all be better off with fewer religious disputes. Gregory reviews, among others, Locke, Jefferson, and Tocqueville, noting that where we have ended up is with the dominance of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, which is not really Christianity at all, and that end was, in retrospect, inevitable.

As Gregory points out, a human community of not-wholly autonomous individuals is the necessary bedrock of both the Christian life and of any healthy society, in its living, in its transmission, and in its recognition and practice of virtue. Instead, what we have is Charles Taylor’s “secular age.”

Gregory focuses on the role of the state, in particular the American judiciary, in the dissolution of truth claims, but does not focus on the increasing use of the state to repress orthodox Christian belief, though the latter is also a necessary consequence of the former. In any case, the system we have ended up with “also meant the separation of politics from morality—or rather, a transition from a Christian ethics of the good to a secular ethics of rights in combination with a distinction between public and private spheres in conjunction with the privatization of religion.”

It is the consequences of that separation that are the topic of Gregory’s fourth thread, “moral discourse and moral behavior”—more precisely, the subjectivizing of it. Here, Alisdair MacIntyre, a man whose revival has come, if it ever really left, is front and center.

MacIntyre’s project (his book, After Virtue, is on my Reaction reading list, of course, for the bedrock of his claims is the rejection of supersessionism) was the revival of Aristotelean concepts of virtue, a sally against Enlightenment rejection of the same and with an inescapable logical end in Christianity.

MacIntyre sought to restore the teleology of Man (a concept that ninety-nine out of a hundred people today, chosen already for the rare characteristic of knowing what “teleology” means, would reject as equivalent to believing in mermaids—nice to imagine, silly to believe in). By this means, relativism would be dispelled, emotivism rejected as the basis for answering Life Questions, and rational moral discourse restored. Up with the common good, down with John Stuart Mill.

Much of this chapter is taken up with how we got to the point where MacIntyre had to rescue the past to inform the future. Again, naturally, it’s a result of the Reformation (a cause Gregory claims MacIntyre missed, or ignored), but the Reformation’s exaltation, in effect, of individual choice was, again, an understandable reaction to the failures of most of Christendom to live up to its ideals, most centrally that of caritas.

The usual suspects in removing virtue from modern political life, including Machiavelli and Nietzsche, also appear. Gregory further ties the “jettisoning of the ethics of the good” to the ever increasing demands for emancipation and for consumer goods.

Still, Christian virtues informed politics and society—until very recently, when they began to fade, allowing delusional people like John Rawls to believe that somehow Christian virtues can be derived without Christianity.

The end result, it is not difficult to realize, is that as the animating energy of Christianity dissipates from within the body politic, we will return to a pre-Christian time, where none of the virtues we take for granted, even if only honored in aspiration, are recognized at all. Without Christianity (or an equally powerful moral framework, none other of which has ever existed in or informed the West), the very idea of “human rights” is incoherent nonsense.

A recurrent theme of this book, and perhaps the key point Gregory aims to prove, is that “[t]he persistent, even adamant, positing of rights has no evidentiary basis given the metaphysical assumptions and epistemological demands that govern not only the natural sciences, but knowledge-making across the disciplines in the academy.” And since the state has been brought in to use ever greater force to ensure ever greater emancipation, where the only moral crime is failing to subjectivize morality, disaster awaits, or, actually, is unfolding as we speak.

The fifth strand is “human desires and capitalism,” or, as the chapter title says, “Manufacturing the Goods Life.” This expands on a point in the previous chapter, that consumerism dictated by individual unbridled choice substitutes, in many ways, for the common good. After all, nature abhors a vacuum, and something must fill the human desire for meaning.

And, choosing among modern options, if you don’t seek transcendence through the ideology of emancipation, for yourselves or others, consumerism is another, more peaceful and perhaps more enjoyable, way to fill your life. While Gregory discusses Max Weber’s theory of the Protestant origin of modern capitalism, this is really a different phenomenon from what Weber identified (leaving aside how right Weber was). Gregory instead ties the rise of consumer culture to the post-Reformation Dutch, with their turning aside from confessional differences and the refocusing on profit and consumption, and the spread of that view in the wake of weariness of religious disputes.

Prior to the Reformation the goods culture was always formally rejected by Christianity, as a failure to implement caritas in a world that viewed economics as zero-sum, though that hardly prevented greed. Money (and especially money, rather than barter), not itself inherently wrong and something that might, if properly viewed and handled, promote human flourishing, nonetheless often subverted the common good by inflating greed through its ease of use and by itself becoming the object of human desire.

Moreover, it tended to depersonalize social relationships. But the turn to a monetized, market economy had its own inexorable logic and internal pressure, so even before the Reformation it was changing Christian ways, and the Reformation, once more, with its fragmentation, accelerated that process.

This was true even though many of the reformers themselves were far more focused on suppressing greed than the princes of the medieval Church. This result came about, again, because of the new primacy of the individual’s determination of conscience, and because of the rejection of teleological virtue ethics (à la MacIntyre) in exchange for, in most cases, a theology that denigrated or rejected works as relevant to salvation.

Nor were Catholics immune; Gregory cites the motto of the Spanish military captain Bernardo de Vargas Machuca, in 1600: “By compass and by sword / More and more and more and more.” (Gregory does not note that Vargas Machuca was a main propagandist for the Spanish conquest of the Americas, and for the subjugation of the inhabitants—he also attempted to refute Bartolomé de las Casas’s harsh criticism of the Spanish conquests and the Spanish treatment of the natives).

Toleration, starting with the Dutch, was indeed one effect of the primacy of commerce and money, but there were other, undesirable, knock-on effects. This new consumerism mostly affected the upper crust, and was often justified as familial duty, not a mere “piling up of unnecessary consumer goods for oneself,” though this itself tended away from the common good, and created new social distances and new “varieties of social othering,” or, viewed at from another angle, new ways to seek the approval of others, as Adam Smith analyzed astutely.

Governments soon enough discovered that all this made for easier-to-govern and happier subjects, who paid more taxes, so these lines of development were naturally encouraged. And, in time, the Enlightenment formally endorsed avarice as the backbone of a good and well-run society. Today, we are the unlucky beneficiaries of these centuries-long developments, where meaning is sought through the “goods culture,” and no meaning can be found.

A common response to such lines of thought is that whatever may be the moral drawbacks of the pursuit of money, acquisitiveness drives society forward in terms of beneficial material progress, though the exact mechanism for this is often disputed. Gregory seems to reject this linkage; I am not so sure he is correct.

While it is certainly true that the Scientific Revolution had nothing to do with the Enlightenment, and the modern world in all its technological might, created wholly by the West, would probably exist in much the same form if the Enlightenment had never happened, it seems to me that the habits of thought revolving around money are necessary for creating the economic value, the formation of assets originating from human effort, that makes the modern world what it is materially, and capable of achieving the advances we have made.

Critiques of consumerism are rarely as historically oriented as Gregory’s, but they typically ignore this question, and they also suffer from a lack of clarity as to whether consumerism is bad because it is immoral, or because it causes some form of harm, to people or to the world. As with other modern critics, Gregory basically says both are the reason, citing, for the latter contention, global warming and other environmental impacts.

But this implies that if the harms can be alleviated, especially by technology, there is less of a problem, and that’s not really what Gregory means. Along the same lines, he certainly admits that raising up most of humanity, and all of Western humanity, from destitution contributes to human flourishing, but there is no clear dividing line in that process, such that it, absent some countervailing force, seems like it must necessarily end in some version of today’s “goods culture.” In the end, Gregory notes that “the manufactured goods life is needed to hold Western hyperpluralism together,” which is probably true, but it seems to me the manufactured goods are necessary, both to exit destitution and to arrive at our beneficial technological advances, but the hyperpluralism is not. That is, you could imagine a world where manufactured goods are more common, and receive more focus, than in the medieval barter economy, but still do not exercise the same grip on the average individual, who receives meaning from other sources tending to the common good.

The book’s sixth thread is “the relationship between higher education and assumptions about knowledge.” Here, we talk about the “secularizing of knowledge,” primarily in universities. We return to the division, unnecessary but perhaps inevitable in historical context, between faith and science.

This is an area Gregory cares deeply about (he is, after all, a university professor) and the analysis is penetrating and detailed, citing a wide range of thinkers and thoughts, from Erasmus’s Novum Instrumentum to Bacon’s New Atlantis. Continuing his overarching theme, Gregory blames the Reformation, of course, along with the naïve belief among some Catholics, such as Erasmus, that more individual focus on scriptural interpretation would lead to moral transformation among those leading flawed lives.

For other reasons, as well, such as the desire for comity among academics corresponding with each other, faith was more and more “downgraded to subjective opinion.” Again, the state contributed to and concretized this process, and even explicitly confessional centers of learning adopted, in effect, univocity and “neo-Arian” doctrines, since their second-rate thinkers were unable to compete with the flood of top-quality Enlightenment thought, and the early modern papacy was no use at all in this competition.

So, today, secularism utterly dominates universities, and, if questioned, a false supersessionist narrative is offered to explain why.

Viewing responses to this book, most come from Protestant evangelicals, who dislike it because it blames their forebears, though they try to conceal that ground for their dislike, and fail. Most interestingly to me, Gregory seems to have some kind of relationship with the liberal public intellectual Mark Lilla (who I had thought is Jewish, since he is very knowledgeable about Judaism, but apparently he is an apostate Catholic).

It is interesting to me because there is no obvious reason for the two to cite each other, yet Gregory’s book repeatedly cites Lilla, and Lilla cites, or attacks, Gregory in his book The Shipwrecked Mind. I agree with Lilla—the correct way to view Gregory’s work is as “a shadow-puppet play on the wall of some Vatican cave.”

Lilla means that negatively, but I mean it positively. What Gregory is laying is groundwork for a revival, not a return, and a shadow-puppet play is as good a way to introduce that as any. In his lengthy discussion of Gregory in his short book, Lilla accuses Gregory of advocating for a return to the “Road Not Taken”—in other words, that we should return to the crossroads, and turn north instead of south.

This is true enough, I think. But Lilla takes this to mean that Gregory would disagree with his own thought, “The lesson of Saint Augustine remains as timely as it was fifteen hundred years ago: that we are destined to pave our road as we go.” But Gregory would say the same, since we now are where we are—just that our paving stones should be constructed based on what we have learned of road engineering from observing our past.

Gregory ends with a brief suggestion that he wants to avoid nostalgia. He sums up, “[M]edieval Christendom failed, the Reformation failed, confessionalized Europe failed, and Western modernity is failing, but each in different ways and with different consequences, and each in ways that continue to remain important in the present.”

Gregory does not recommend a way forward (he notes “I wish this book could have had a happier ending”), but it is clear enough to me how he fits into current reactionary thinking. He provides an exhaustive historical and theoretical underpinning for Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option, which is, contrary to what many people seem to think, not a call for withdrawal, but a call for renewed Christian community and small-scale focus on the common good and human flourishing, both as an inherent good and to act as the scaffold for a future society-wide renewal, in a way that cannot be seen now.

After all, the very name “Benedict Option” is taken from a phrase of Alisdair MacIntyre’s, who plays a major role in this book. Dreher is much more of a popularizer than Gregory, though, and I have to admit that this book is really only suitable for those strongly interested in either history or intellectual calisthenics, or, preferably, both. Taken together, though, Dreher’s and Gregory’s thought is a very strong core for a new construction, informed by what has gone before.

Charles is a business owner and operator, in manufacturing, and a recovering big firm M&A lawyer. He runs the blog, The Worthy House.

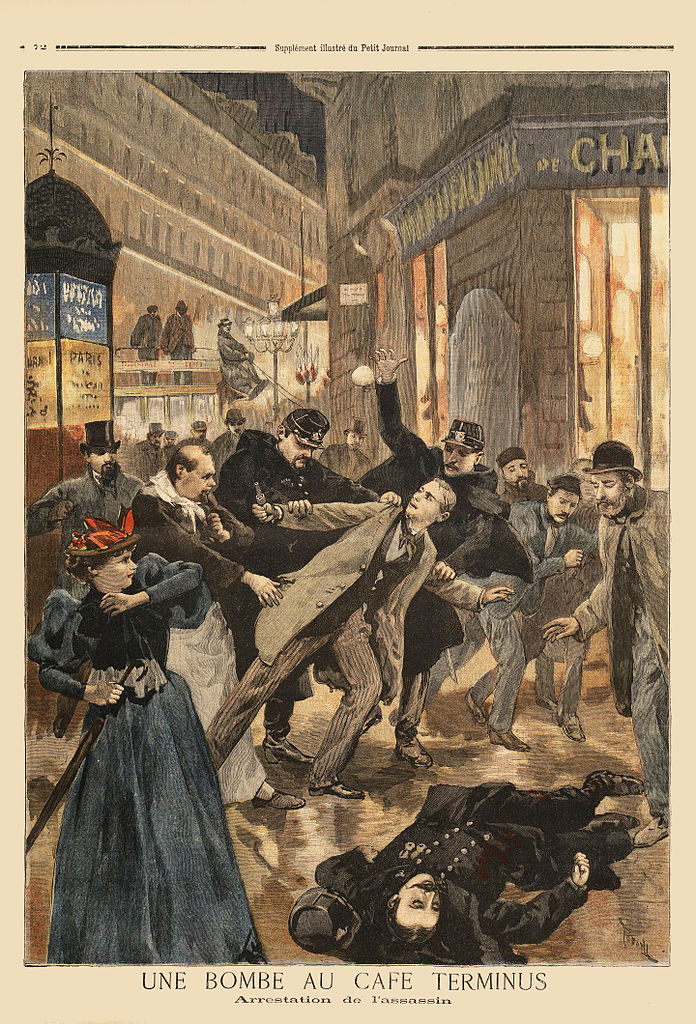

The photo shows, “Student Cafe” by Jean Beraud, painted in 1889.

(published in 1939) that came on the market tended to be rather exorbitantly priced. Money-issues aside, this scarcity also meant that few had access to the important account given in this often moving memoir.

(published in 1939) that came on the market tended to be rather exorbitantly priced. Money-issues aside, this scarcity also meant that few had access to the important account given in this often moving memoir.