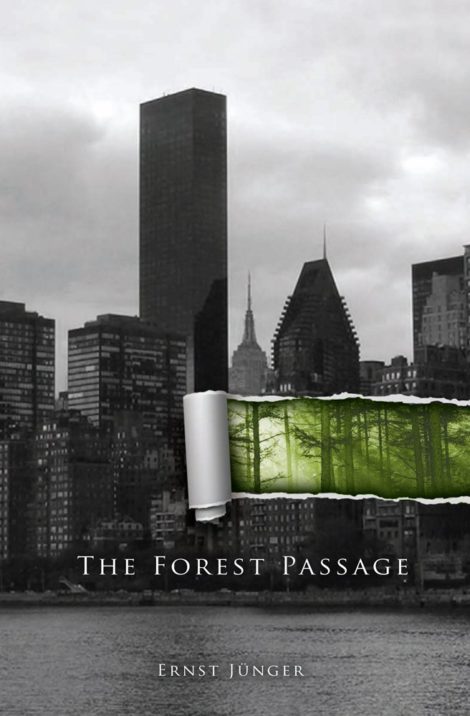

Ernst Jünger was one of the more fascinating men of the twentieth century. Remembered in the English-speaking world primarily for his World War I memoir, The Storm of Steel, he was famous in Europe for a range of right-leaning thought spanning nearly eighty years (he lived from 1896 to 1998).

His output was prodigious, more than fifty books along with voluminous correspondence, and not meant or useful as a seamless ideology, although certain themes apparently recur. This book, The Forest Passage, was published in 1951, and is a compelling examination of how life should be conducted under modern ideological tyranny.

Jünger’s answer is jarring, both in its originality, and in its flat rejection of any relevancy of those modern (though failing) totems, liberal democracy and egalitarianism. Jünger was no Nazi; he contemptuously rejected their efforts to profit off his reputation, and was tangentially involved in the Stauffenberg plot. But he had just as little use for modern democracy or liberalism; much of his thought seems to have revolved around a type of social and political elitism with a spiritual core. It appears that The Forest Passage was his first exploration of the specific topic of resistance to tyranny; he developed the thought in this book further with a novel published in 1977, Eumeswil, which I have not read.

profit off his reputation, and was tangentially involved in the Stauffenberg plot. But he had just as little use for modern democracy or liberalism; much of his thought seems to have revolved around a type of social and political elitism with a spiritual core. It appears that The Forest Passage was his first exploration of the specific topic of resistance to tyranny; he developed the thought in this book further with a novel published in 1977, Eumeswil, which I have not read.

This is quite a difficult book to read; it can be opaque, and it assumes the reader’s recognition of various oblique references (I had to look up that Champollion was a decrypter of Egyptian hieroglyphics, for example).

This 2013 edition, from Telos Press, is greatly helped by occasional notes (though more would have been better), and an outstanding introduction from Russell Berman. Most of Jünger’s books have not been translated, and Telos, a left-leaning entity, has usefully been translating and reprinting at least a few, all of which I have bought and am now working through as I explore alternatives to our own crumbling social and political system.

Jünger had lived through World War I (barely), receiving numerous awards for bravery, and become famous for The Storm of Steel. That book was and is often criticized for being the mirror image of anti-war writings, from the British war poets to All Quiet on the Western Front.

Jünger did not oppose the war, even after its disastrous end; he liked certain aspects of it, regarding them as spiritually valuable, even epic. (In this he was much like Erwin Rommel, who also wrote a memoir that made him famous, though Rommel was practical about his like for war, not spiritual).

During the interwar period Jünger was a key figure in the so-called “Conservative Revolution,” the loose movement of intellectuals (including Oswald Spengler and Carl Schmitt), opposed to Weimar and democracy, and more broadly to modernism and individualism, as well as to the coming thing, Communism.

During the war, Jünger also opposed the Nazis, mostly passively, although he wrote a novel implicitly critical of Hitler (On The Marble Cliffs), something he could get away with because of his fame. After the war, for decades, he was a leading public intellectual, never forgiven by the dominant Left for his rightist views, but able to haughtily ignore their carping, and widely honored until the end of his life.

In 1951, of course, Germany stood between the immediate past of Nazism and the immediate threat of Soviet Communism. This is the backdrop of The Forest Passage, and the book cannot be understood without keeping it in mind. That said, Jünger’s thought is directed at challenging any ideological tyranny, which includes, increasingly, our own Western “liberal democracy.”

What should a person oppressed by such a tyrannical state do? The book is really an answer on two levels: What he should do in the external world, and what he should do in his internal world. More precisely, it is an exploration of how the latter should drive the former. Jünger was not George Orwell, predicting the victory of global tyranny.

In fact, he was quite optimistic about the future, predicting elsewhere that ultimately technology would allow a global state, a “planetary order,” to emerge under which humans could flourish. But in The Forest Passage he was interested in tyrannies present or future, whatever their origin, and how one should live under them.

Jünger begins by discussing how in an oppressive state the mere act of voting “no” where ninety-eight percent vote “yes,” as demanded and enforced by the state and by one’s fellow voters, is an act of rebellion.

It does not matter that the state actually wants fewer than one hundred percent to vote “yes,” because that way the vote seems more realistic, and, more importantly, the state can thereby justify further action against its opponents, whose existence is by the vote made visible to all, and also therefore the need for their suppression so that Utopia can finally be reached (although, as in Zeno’s Paradox, it can never actually be, for that would deprive the dictatorship of its reason for seeking more power).

“Dictatorships cannot survive on pure affirmation—they need hate, and with it terror, to provide a simultaneous counterbalance.” (This is true also of proto-dictatorships, such as today’s American Left. As Shelby Steele has recently pointed out, the Left existentially needs to see racism everywhere, so they can keep whipping up hate to augment their power through terror).

Rather, the point of, and the meaning of, the vote “no” is not to “shake the opponent, but [to] change the person who has decided to go through with it.” He, by the choice of voting “no,” or by any equivalent choice, becomes a “forest rebel,” transformed into something new, who takes the “forest passage,” taking actions that are also something new.

Here, “something new” is not a throwaway line of mere contrast to the existing tyranny. The newness of the forest rebel’s path is critical to Jünger’s analysis. The man who votes “no,” the freshly minted forest rebel, is not trying to turn back to the old ways of democracy, or any other specific prior political system. Those are dead and gone, along with his own past individual nature. He is on a new path.

“This is why the numerous attempts under the Caesars to return to the republic had to fail. The republicans either fell in the civil war, or they came out of it transformed.” You cannot go back. The way is shut. While Jünger is focused on tyranny, this principle is more generally applicable, as Jünger’s reference to Rome shows.

In fact, I think that newness is a critical element in planning our own future. For Reaction, something I wish to implement after the inevitable rupture as our own system dies, is properly viewed not a turning back, as its caricaturists and opponents would have it, but the creation of a new thing informed, in part, by the wisdom of the past.

This is what Jünger calls “retrospection,” conducted by a small minority, made possible because “in the nature of things,” “when catastrophes announce themselves . . . the initiative will always pass into the hands of a select minority who prefer danger to servitude.” Failing to grasp that newness is essential, and must be accepted and made central, will lead to nostalgia, and thence to dissonance and failure of all political plans and action.

What most of all characterizes the forest rebel is his devotion to freedom. He is internally completely free, and he works for external freedom as well. These things set him apart from both the tyrannical state and the mass of men. But it essential to note that Jünger is not a libertarian. His idea of freedom has very little in common with Robert Nozick and less with Milton Friedman.

The freedom of the forest rebel is not the freedom to do as he pleases; it is not the unbridled autonomy and atomized individualism that were the poison at the heart of the Enlightenment and are the engine of its destruction. Those are “unworthy interpretations” of freedom; Jünger specifically sneers at the French Revolution. Nor is it exactly the older conception of freedom, the ability to choose rightly, although it is much closer to that than to libertarianism.

Rather, it is a modernized version of that, consisting of two related threads. First, and concretely, the refusal to obey or even acknowledge the commands of an oppressive and malevolent, state. Second, and abstractly, a spiritual core with which the forest rebel analyzes his decisions, informed by a rejection of degrading “automatism” and its consequence, “fatalism,” in favor of self-rule and of the virtues of “art, philosophy, and theology.”

Jünger’s analysis of voting under tyranny prefigures Václav Havel’s famous analysis of the grocer who refuses to put the sign, “Workers of the World, Unite!” in his shop window. For Havel, this is refusing to “live within a lie,” which allows the grocer to reclaim his identity and dignity, but for which he must pay, because even this minor act of defiance threatens the entire regime, even though it has no explicitly political intent or meaning.

The forest rebel’s attitude is much the same. And even though Jünger focuses more on the rebel’s internal mental state than his specific external actions, he is quite clear that he expects the forest rebel, ultimately, to act, rather than merely ruminate.

Confusingly, at the same time Jünger sometimes seems to say that the forest rebel mostly lives and acts completely in isolation, in the forest, a type of garden, but a solitary one. True, the forest rebel battles “Leviathan,” but his is sometimes characterized as a holding action, to keep himself from the degradation of the masses who acquiesce, and, implicitly, to form the core of something to come.

This ambiguity as to the actual actions to be taken may be deliberate, for Jünger knows that context dictates action, and he has no Marxist-flavored belief in inevitable turns of history. Ultimately, he says that “The armor of the new Leviathans has its own weak points, which must continually be felt out, and this assumes both caution and daring of a previously unknown quality.

We may imagine an elite opening this battle for a new freedom, a battle that will demand great sacrifices and which should leave no room for any interpretations that are unworthy of it.” Thus, Jünger always returns to the concept of battle, and it is a fair conclusion that is what he expects of the ideal forest rebel. “The task of the forest rebel is to stake out vis-à-vis the Leviathan the measures of freedom that are to obtain in future ages. He will not get by this opponent with mere ideas.”

The forest rebel is therefore exemplified by William Tell, mentioned twice in this brief book. Tell, of course, was the (probably mythical, but no matter) fifteenth-century Swiss crossbowman who shot an apple off his son’s head at the command of the malevolent state, represented by Albrecht Gessler, proxy for the Habsburg dukes who ruled Tell’s canton.

Gessler’s command was punishment for Tell refusing to salute Gessler’s hat, which he had placed on a pole and then required the people to salute, in order to humiliate them and bring low their spirit. Most of us remember that Tell put two crossbow bolts in his belt, and when asked by Gessler, after successfully shooting the apple, why he had done that, replied that the second was for Gessler, had Tell hit his son.

Most of us probably do not remember the second act of the story—Tell escapes, to the forest, and then soon ambushes Gessler and assassinates him, starting a successful rebellion. (By coincidence, I bought several books on Tell for my children a few weeks ago.

I am glad I did that; these are important lessons and guides to action, and I am willing to bet zero children are told Tell’s story in most schools today.) Tell was no libertarian—he was a free man in a free society, but he was bound by, and loyal to, that society and its rules. His was the freedom of Leonidas, not of Hugh Hefner.

Tell is, however, not the only rebel Jünger praises—one other, an anonymous man, gets his nod. Speaking of the breakdown of the rule of law in 1933 Berlin, and the acquiescence of the population in Nazi suppression of political opponents, he says, “A laudable exception deserves mention here, that of a young social democrat who shot down half a dozen so-called auxiliary policemen [i.e., NSDAP storm troopers] at the entrance of his apartment.

He still partook of the substance of the old Germanic freedom, which his enemies only celebrated in theory.” It’s hard to miss Jünger’s message, and it’s not that the forest rebel should meditate silently on freedom while sitting at home.

Both by such examples, and by explicit statements, Jünger is clear that his contemplated rebellion is not one of raising an army, but of ad hoc or guerrilla warfare. When striking physically at the state, the forest rebel is not to worry unduly about the mechanics of rebellion. Instead, he must focus on tools and getting the party started. The details will take care of themselves.

“In regard to organizing maneuvers and exercises, setting up bases and systems adapted to the new form of resistance—in short, in regard to the whole practical side of things, people will always emerge who will occupy themselves with these aspects and give them form.” Therefore, “More important is to apply the old maxim that a free man be armed—and not with arms under lock and key in an armory or barracks, but arms kept in his apartment, under his own bed.”

Moreover, in matters of arms, a man “makes his own sovereign decisions.” Jünger would not approve of today’s gun grabbers, any more than he did of the gun grabbing by the Nazis or the Bolsheviks, because he saw clearly what the seizure of arms always made possible and was, and is, intended to make possible, whether by Lenin or Dianne Feinstein—the triumph of the totalitarian state.

Even aside from open rebellion, though, the forest rebel has an outsized effect relative to his numbers. He is a “chemical reagent,” because he is (physically) surrounded by others, he will influence them. Hence the growth in police in oppressive states, and “these wolves [the forest rebels] are not only strong in themselves; there is also the danger that one fine morning they will transmit their characteristics to the masses, so that the flock turns into a pack. This is a ruler’s nightmare.”

(Here Jünger departs from Havel, since Havel thinks that the “wolf” is actually representative of the majority of people, and Jünger thinks most people are intellectually complicit with the tyrannical state, which is perhaps why Havel rejected revolt, preferring the power of example.)

How are those characteristics transmitted? Through imagination, which “provides the basic force for the action.” Imagination is not itself enough, but it, poetry writ large, provides the spark. I would only add that the impact of imagination cannot be predicted. Cometh the hour, cometh the man, but it is impossible to know anything more in advance, which makes it essential that the forest rebel keep the powder needed to set alight the conflagration dry and ready to hand.

Jünger, and the forest rebel, laugh at the idea of egalitarianism as a denial of basic reality. The forest rebel is an aristocrat, not of blood, but of virtue, which is real aristocracy. To Jünger and the forest rebel, it is blindingly obvious that all men are not equal—they may be equal before God, but the forest rebel is the superior of the masses, for his choice is hard and risk-filled, yet objectively better.

Not for Jünger the idea that each man’s choice is merely each man’s choice. No, some choices are better, and therefore, the people who make them are superior. They are a “heroic elite.” This aristocracy is open to all; Jünger says that the freedom he calls for “is prefigured in myth and in religions, and it always returns; so, too, the giants and the titans always manifest with the same apparent superiority.

The free man brings them down; and he need not always be a prince or a Hercules. A stone from a shepherd’s sling, a flag raised by a virgin, and a crossbow have already proven sufficient.” David the son of Jesse, Joan of Arc, and William Tell are the elite.

“This miracle has happened, even countless times, when a man stepped out of the lifeless numbers to extend a helping hand to others. . . . Whatever the situation, whoever the other, the individual can become this fellow human being—and thereby reveal his native nobility.

The origins of aristocracy lay in giving protection, protection from the threat of monsters and demons. This is the hallmark of nobility, and it still shines today in the guard who secretly slips a piece of bread to a prisoner. This cannot be lost, and on this the world subsists.”

It is not only in his demand for private weapons and his disdain for egalitarianism that Jünger is wildly not politically correct, a bone in the throat of today’s Left. Not for Jünger other modern ideas, such as false gender equality or the idea that the liberal democratic state is the real bulwark of our real freedoms.

“Long periods of peace foster certain optical illusions: one is the conviction that the inviolability of the home is grounded in the constitution, which should guarantee it. In reality, it is grounded in the family father, who, sons at his side, fills the doorway with an axe in hand.” This is not a fashionable set of ideas, but I’m betting all of them are about to gain fresh traction.

Along the same lines, it is very clear, though mostly below the surface in this book, that Jünger thinks highly of vigorous religious belief, as opposed to modern godless ideologies, as a key part of a forest rebel’s thought. A transcendent belief is necessary for the forest rebel to succeed, or even to be a forest rebel.

Jünger praises “churches and sects” as a counterpoint to what drives the tyrannies he fears, “natural science raised to the level of philosophical perfection.” (He also specifically exalts Helmuth James von Moltke, the deeply Christian founder of the Kreisau Circle, executed by the Nazis in 1945).

Faith means freedom; materialism reinforces tyranny. Religion (implicitly Christianity, for Jünger tells us Christ has shown the way to conquer the root of all fears, the fear of death) is good, it prepares man “for paths that lead into darkness and the unknown,” though not enough by itself, and in any case it will always be persecuted by the tyrannical state, which insists on absolute power. Thus, we find “tyrannical regimes so rabidly persecuting such harmless creatures as the Jehovah’s Witnesses—the same tyrannies that reserve seats of honor for their nuclear physicists.”

All this is very interesting, and offers much material for reflection. We get a very good idea of the type of system Jünger does not want—modern ideological tyrannies, in short, the heirs of the French Revolution. We understand the mechanism for resistance and eventual overthrow. But what system does Jünger want? On that he is less clear, but there are occasional glimpses.

It is most definitely not modern liberal democracy, although again there is little direct criticism of such modern systems, even if in the 1930s Jünger had vociferously criticized Weimar.

We can get a clue, though, when Jünger refers to the “virtuous way” as derived from “simple people . . . who were not overcome by the hate, the terror, the mechanicalness of platitudes. These people withstood the propaganda and its plainly demonic insinuations.

When such virtues also manifest in a leader of people, endless blessings can result, as with Augustus for example. This is the stuff of empires. The ruler reigns not by taking but by giving life. And therein lies one of the great hopes: that one perfect human being will step forth among the millions.” That is, Jünger wants a Man of Destiny, to free us of ideological tyranny, and lead us to the sunlit uplands.

This resonates very strongly with me; as I have written elsewhere, we await that Man of Destiny, an Augustus for the new age, and he will not come borne on the wings of so-called liberal democracy.

My feeling is that as the cracks spread in the West, tyrannies and oppressions of one sort or another are increasingly likely to offer to oppress us, in a way that seemed inconceivable even fifteen years ago, and they will have to be resisted, with shot and shell. Who could have predicted, so soon after the fall of Communism and the apparent end of ideological tyranny in the West, that a book like The Forest Passage would become relevant again? Not me. But that’s where we are, and perhaps some of Jünger’s thought will shorten the path through, and time spent in, the forest.

Charles is a business owner and operator, in manufacturing, and a recovering big firm M&A lawyer. He runs the blog, The Worthy House.

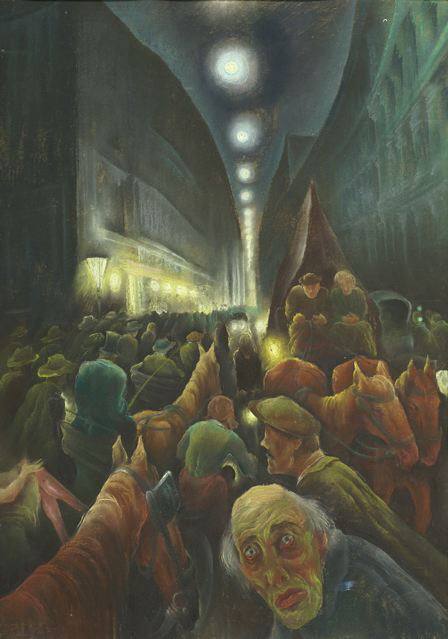

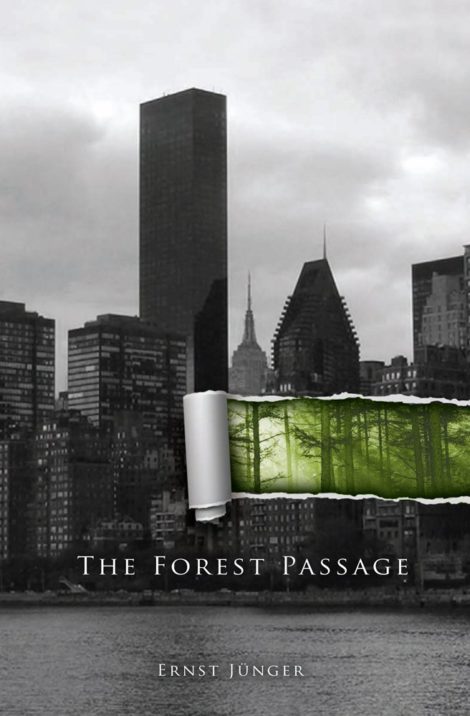

The photo shows, “Leipziger Street Berlin,” by Albert Birkle, painted in 1923.