Miraculous And Holy: Famous Russian Icons

Orthodox Christianity, the most influential confession in Russia, provides the faithful with many objects of worship, especially icons: beautiful, spiritual and believed (by some) to perform miracles and protect the country from the enemy.

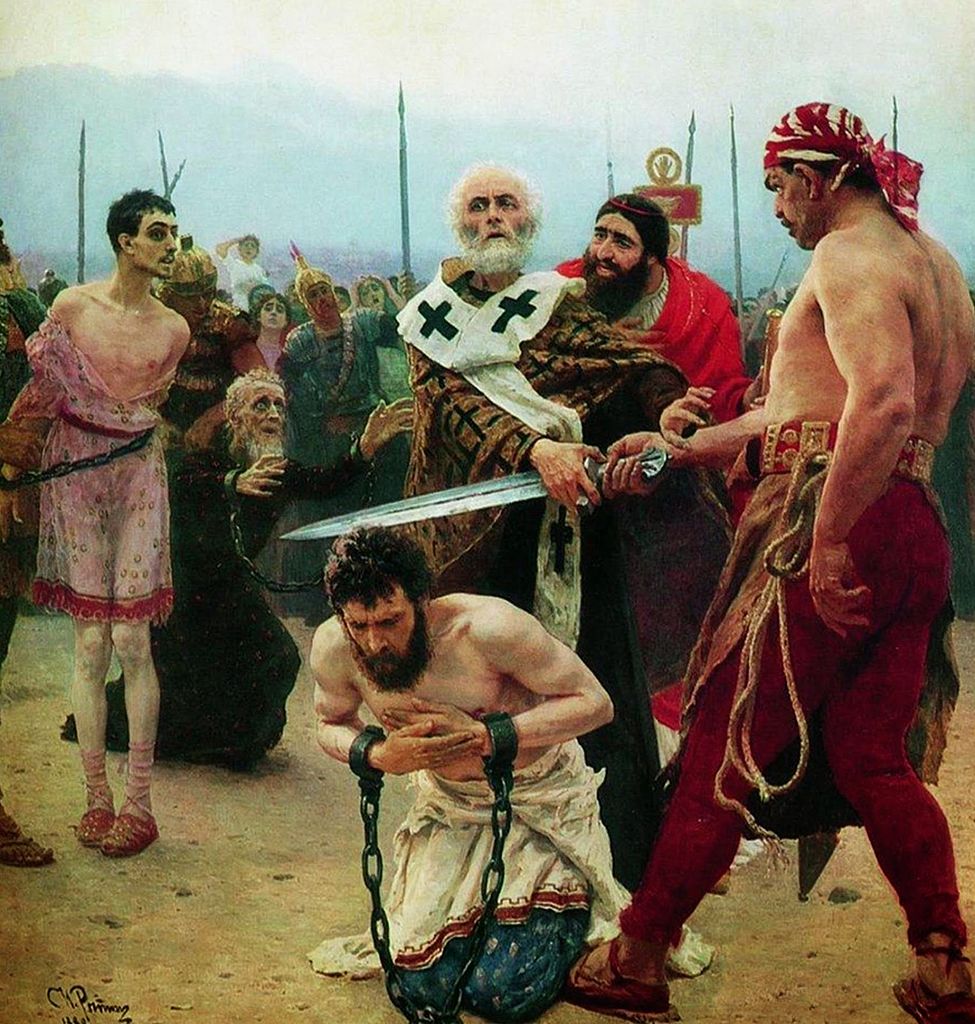

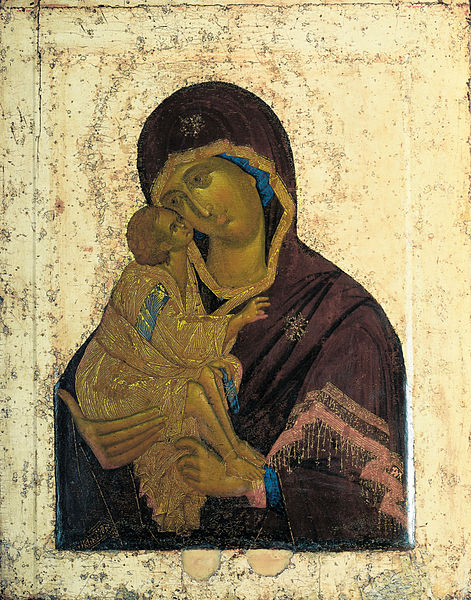

Our Lady of Vladimir

One of the finest examples of Byzantine iconography is the Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus snuggling up to her cheek. Thisicon was sent to Rus as a gift in  the early 12th century. The Patriarch of Constantinople gave it to a Russian prince; subsequently it changed owners during periods of wars and strife, finally finding a home in the city of Vladimir.

the early 12th century. The Patriarch of Constantinople gave it to a Russian prince; subsequently it changed owners during periods of wars and strife, finally finding a home in the city of Vladimir.

In 1395, Prince Vasily of Moscow took the icon to his city, seeking the help of God – that year Tamerlane, a powerful and ruthless conqueror from Middle Asia turned his eye on Moscow. His army would have defeated the Russians and burned the city, but Muscovites prayed to Our Lady of Vladimir. Tamerlane changed his mind and decided not to invade. Of course, believers attribute this to the Virgin Mary.

Two more times, in 1451 and 1480, the pattern repeated: Moscow was just about to be invaded, defeated and burned by the Mongols, but in the end they didn’t fight the Russians.Orthodox believers were sure that the icon saved their city. This is why the icon is believed to be miraculous.

Where to find it today: in St. Nicholas Church near the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

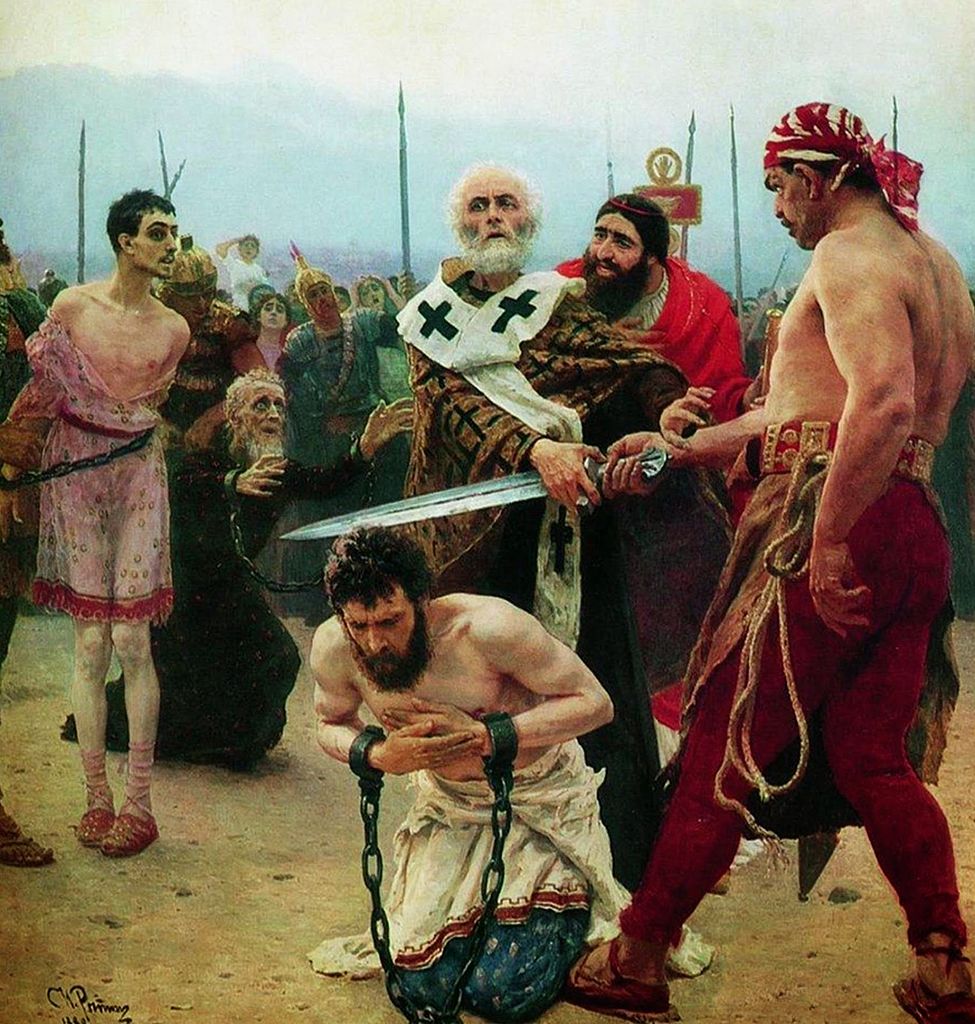

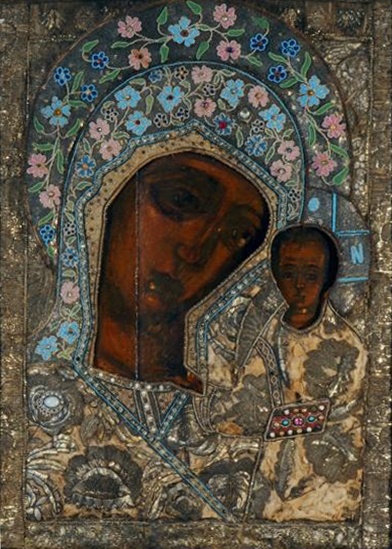

Our Lady of Kazan

Yes, Russians love the Virgin Mary, so here is another Byzantine icon of her. Lost in the 15th century, it was mysteriously found 140 years later, in 1579, after a great fire in Kazan. According to legend, the Lady of Kazan came to a little girl, Matrona, in her sleep and asked to look for her image in the ashes. The girl listened and later became a nun in the monastery where the icon was kept.

great fire in Kazan. According to legend, the Lady of Kazan came to a little girl, Matrona, in her sleep and asked to look for her image in the ashes. The girl listened and later became a nun in the monastery where the icon was kept.

Much like her “sister” in Vladimir, the Lady of Kazan was later moved to the capital. In 1612, the Russian army carried it as a holy banner during their battle against the Poles who occupied Moscow – and won. Since then, the Virgin Mary of Kazan is also known as the Holy Protectress of Russia.

In 1904, the unspeakable happened: someone stole the icon from the monastery in Kazan. Since then, the fate of one of Russia’s most worshipped symbols is unclear. Nevertheless, there is an excellent copy of the original icon, which traveled the world and was given back to the Orthodox by Pope John Paul II.

Where to find it today: in the Bogoroditsky Monastery of Kazan (copy)

“The Trinity” by Andrei Rublev

This is the first (and the last) non-Virgin-Mary icon in this list and one of the few proven conclusively to be created by Andrei Rublev, the great Russian icon painter who lived in the 15th century. There are no legends or rumors around this icon; it’s not considered miraculous. Yet it’s one of the most beautiful pieces of art and one of Russia’s symbols.

painter who lived in the 15th century. There are no legends or rumors around this icon; it’s not considered miraculous. Yet it’s one of the most beautiful pieces of art and one of Russia’s symbols.

“The Trinity,” also called “The Hospitality of Abraham,” portrays three angels that, according to the Bible, came to the house of Patriarch Abraham symbolizing “one God in three persons” – the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit. The icon is astonishingly harmonic and tranquil. “It shines with the highest, unearthly light that we can see only in the works of geniuses,” said Russian painter Igor Grabar about “The Trinity.”

Where to find it today: in the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

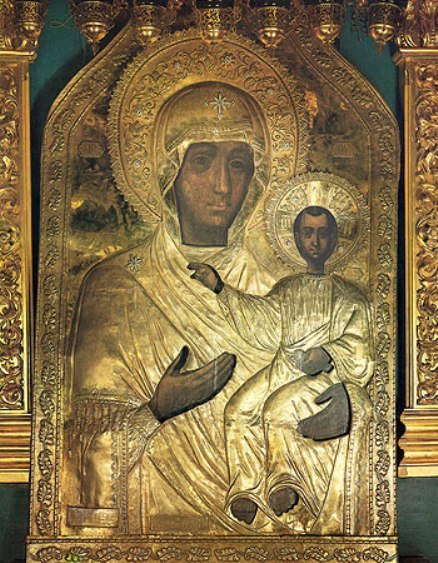

The Theotokos of Smolensk

Like we said before, for Russians there is no such thing as too many miraculous icons of the Virgin Mary. This one, rumored to be painted by St. Luke the Evangelist, was given to Prince Vsevolod by the Byzantine emperor in 1046 when Vsevolod married his daughter, thus turning Kievan Rus’ into a powerful ally of the Orthodox Church.

Evangelist, was given to Prince Vsevolod by the Byzantine emperor in 1046 when Vsevolod married his daughter, thus turning Kievan Rus’ into a powerful ally of the Orthodox Church.

Kept in the city of Smolensk (400 km west of Moscow), this icon was believed to protect Russian lands from western enemies. That’s why in 1812, when Napoleon invaded Russia, the army took the icon to Moscow and the whole city prayed for salvation.

The original icon, however, didn’t survive another invasion from the West: during World War II, when Nazi Germany occupied Smolensk in 1941-1943,Theotokos was lost. Now the city owns only an exquisite copy.

Where to find it today: in the Cathedral Church of the Assumption, Smolensk (copy).

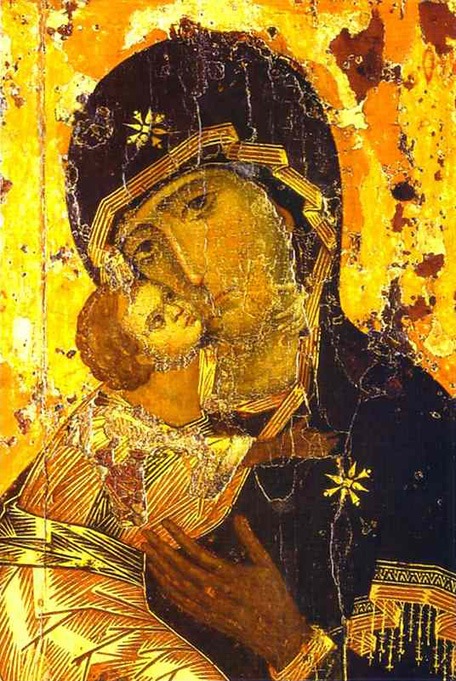

Our Lady of the Don

Yet another of Russia’s many ‘ladies,’ this one is believed to be painted by Theophanes the Greek, Andrei Rublev’s teacher and another great icon painter. Legend says the Cossacks gave this icon to Prince Dmitry of Moscow a day before he defeated the Mongols in the glorious battle of Kulikovo. Though it’s most likely a fake, Our Lady of the Don had its fame as Russia’s protector, like the others on this list.

Theophanes the Greek, Andrei Rublev’s teacher and another great icon painter. Legend says the Cossacks gave this icon to Prince Dmitry of Moscow a day before he defeated the Mongols in the glorious battle of Kulikovo. Though it’s most likely a fake, Our Lady of the Don had its fame as Russia’s protector, like the others on this list.

Where to find it today: in the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Oleg Yegorov writes for Russia Beyond.

The Katechon In Carl Schmitt’s Philosophy

The concept of the katechon first appears in biblical literature with two hapaxlegomena occurring in the second deutero-Pauline epistle to the Thessalonians (2:6-7): “And now you know what is now restraining him [τὸ κατέχον], so that he may be revealed when his time comes. For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work, but only until the one who now restrains [ὁ κατέχων] it is removed.”

In the context of apocalyptic literature, the function of the katechon is to constrain the eschatological enthusiasm of the Christian Thessalonian church who are eagerly awaiting the return of Christ.

The restraint that the katechon enforces is directly related to the forces of evil — the evil one — who brings about disorder and lawlessness. God’s historical agent, the katechon, not only tempers the eschatological enthusiasm for the parousia of Christ, but also by doing so, attempts to restore order in the midst of crisis and chaos.

The image of the katechon is clearly situated within the context of the metaphysical conflict between the forces of good and evil. The period of the eschaton, wherein we wait for the heavenly kingdom to be instituted in our temporal reality, is marked by evil forces.

God, however, appoints the katechon to bring about the necessary stability in these last days. The deeply ambiguous figure of the katechon can thus be viewed both positively and negatively: restraining the forces of evil, but also holding back the return of Christ.

The symbolization of the katechon in Schmitt’s thought is used not only to legitimize his concept of sovereignty, but also becomes the basic structural principle around which the totality of history is to be conceived.

The figure of the katechon is not treated systematically by Schmitt, although it appears frequently between 1942 and 1944 and also in the postwar period between 1950 and 1957.

This later usage of the katechon is revealing. On the one hand, it begins to explain the defensive and apologetic tone of his work after the war, and on the other, by way of this defense, evinces the first major reason for its deployment. Namely, as a justification or legitimization of the sovereign decision: a defence of a concept of the political which would justify the option of the total state to prevent chaos and produce order.

During Schmitt’s time, this chaos would have been a direct reference to the on-going parliamentary crisis under the newly constituted Weimar Republic, as well as the persistent threat of the communist faction, spurred by recent events in Russia and Hungary.

Nowhere more clearly is the defense and desire for order seen in an often-quoted piece of text from Jacob Taubes:

“Schmitt’s interest was in only one thing: that the party, that the chaos not rise to the top, that the state remain. No matter what the price. This is difficult for theologians and philosophers to follow, but as far as the jurist is concerned, as long as it is possible to find even one juridical form, by whatever hairsplitting ingenuity, this must absolutely be done, for otherwise chaos reigns. This is what he [Schmitt] later calls the katechon: The retainer [der Aufhalter] that holds down the chaos that pushes up from below.”

Schmitt’s interest was in only one thing: that the party, that the chaos not rise to the top, that the state remain. No matter what the price. This is difficult for theologians and philosophers to follow, but as far as the jurist is concerned, as long as it is possible to find even one juridical form, by whatever hairsplitting ingenuity, this must absolutely be done, for otherwise chaos reigns. This is what he [Schmitt] later calls the katechon: The retainer [der Aufhalter] that holds down the chaos that pushes up from below.

For Schmitt, the jurist, no matter the cost, chaos could not rise up (nach oben kommt) to the level of the state; the ‘restrainer’ is necessary, therefore, to suppress (niederhält) this chaos.

As Michael Hoelzl comments, “The katechon is used here as a political and existential category to explain and justify Schmitt’s option for a total state in order to prevent the chaos that threatened the Weimar republic.”

Despite Schmitt having joined the Nazi party and having not regretted this decision in the future, Taubes’ apologetic interpretation of Schmitt’s understanding of the katechon was apparently welcomed by the latter, which lends credence at least to the fact that it was meant to justify a conception of state — and the decision taken by its sovereign — to suppress whatever it saw as the source of evil or chaos.

But more than an apology, the katechon is also the central eschatological principle which gives context to Schmitt’s entire concept of history. This is a Christian eschatology of the present that makes possible a ‘politics of the present.’

In a remarkable passage from Der Nomos der Erde (1950) Schmitt confirms the centrality of the katechon for his understanding of history:

“Ich glaube nicht, daß für einen ursprünglich christlichen Glauben ein anderes Geschichtsbild als das des Katechon überhaupt möglich ist. [I do not believe that for an original Christian faith another view of history other than that of the Katechon is possible.] The belief that a restrainer holds back the end of the world, provides the only bridge between an eschatological paralysis of all human effort and so great historical power like that of the Christian Empire of the Germanic kings.

Schmitt here establishes the katechon as both the condition for immanent politics and authentic Christian faith. Without the katechon which ‘holds back the end of the world (ein Aufhalter das Ende der Welt zurückhält) we enter into a ‘paralysis of all eschatological human effort’ (eschatologischen Lähmung alles menschlichen Geschehens) and lose the explanatory power of the Roman empire and its Christian continuation to maintain itself against the forces of evil and disorder.

A similar conclusion with respect to history was reached in the posthumously published Glossarium: “ich glaube an den Katechon; er ist für mich die einzige Möglichkeit, als Christ Geschichte zu verstehen und sinvoll zu finden [I believe in the katechon: it is for me the only possible way to understand Christian history and to find it meaningful]”.

Even though Schmitt was never explicit about where the katechon was to be found, the places where he does mention it all refer to its function as creating or maintaining order.

In a profound irony, if read from the political and juristic point of view – which is what Schmitt claimed at most he was trying to do — the desire for order in the present, which elicits a politics and eschatology required to maintain it, issues in a performative contradiction in Schmitt’s work.

As Steven Ostovich has noted, “Schmitt developed his political theology as a criticism of legal positivism and its instrumental logic,” but “his concept of the restrainer reintroduces instrumentalism: politics is not substantive but a matter of doing whatever is necessary to maintain order.”

The principle of the katechon in Schmitt’s eschatology is therefore about maintaining a political order, it is properly a ‘politics of the present.’ It defines “the space between the radically spiritual and the purely political. It is the time window, the mean-time, the in-between of the first and second coming of the Lord.”

Calvin Dieter Ullrich is a PhD Candidate at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. His current project involves an analysis of the notion of sovereignty, read alongside postmodern theology.

The photo shows, “Scene from the Apocalypse,” by Francis Danby, painted ca. 1829.

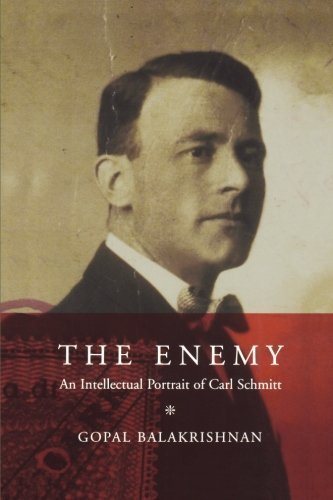

Carl Schmitt: The Man And His Ideas

Carl Schmitt, preeminent antiliberal, is that rare thing, the modern political philosopher relevant long after his time. The simple remember him only for his grasping embrace of Nazism, but the more astute, especially on the Left, have in recent times found much to ponder in Schmitt’s protean writings.

grasping embrace of Nazism, but the more astute, especially on the Left, have in recent times found much to ponder in Schmitt’s protean writings.

He did not offer ideology, as did so many forgotten political philosophers, but instead clear analysis of power relations, untied to any specific system or regime.

So, as the neoliberal new world order collapses, and the old dragons of man, lulled for decades by the false promises of liberal democracy, rise from slumber, such matters are become relevant once more, and Schmitt informs our times, echoing, as they do, his times.

This book, Gopal Balakrishnan’s The Enemy, slickly analyzes Schmitt’s complex and often contradictory writings. Because Schmitt offered no system, and often contradicted himself in sequential writings, or at least offered ideas hard to rationalize with each other, too often he is seen as an “affectively charged symbol, not as someone whose thought could be understood through a comprehensive and systematic study.”

Balakrishnan’s goal is to accomplish that latter task. “My objective is to reconstruct the main lines of his thought from 1919 to 1950 by identifying the problems he was addressing in context.”

The author makes clear up front that he wants to explore Schmitt’s thought, objectively, not through the lens of his association with Nazism: “Those who still insist on adopting the role of either prosecutor or defence attorney in discussing Schmitt can, I hope, be convinced that there are far more interesting issues involved.”

And, critically, while Balakrishnan is a leftist, his views never, as far as I can tell, infect the text in any way—perhaps, in part, because he feels strongly that Schmitt is not himself monolithically on the Right.

I have not read any Schmitt directly, yet, and so I cannot say if Balakrishnan’s summaries of Schmitt’s thought are accurate or complete. But I turned to Schmitt because his name kept coming up in modern books by leftists (and was used by #NeverTrumper Bill Kristol when trying to tar his opponents). Certainly, at first glance, his thought is relevant not only to the Left, but is just as relevant for today’s reactionaries, such as me.

This is because Schmitt’s thought did not revolve around a retreat to the past, imaginary or otherwise. He was not interested in such restorationism; he correctly saw it as a false path. Rather, all of Schmitt’s thought revolved around taking what exists today and, informed by the past instead of by some Utopian ideology, creating the future. He was master of identifying and rejecting the historical anachronism in favor of reality; such clarity is one key to effective Reaction.

Born in 1888, of a provincial Roman Catholic family in the Rhineland, Schmitt studied jurisprudence (which then included political science and political philosophy) in Berlin in the early 1900s.

At that time, the legal philosophy of positivism dominated German thinking. Positivism held that the law consisted only of, and was derived only from, legal pronouncements, and formed a seamless whole through and by which all legal decisions could be made uniformly and predictably, if only one looked hard enough.

This, a modernist concept beloved of liberals, had erased the earlier philosophy of natural law, under which much of the law existed outside specific legal mandates written down in books, whether divinely mandated or the result of custom and human nature.

Schmitt’s early writings expressed some doubt about positivism, which in the pre-war years had come under some attack as permitting, then ignoring, gaps, as well as for ignoring who made the law. The war, however, firmly set his thought on the path it was to take for the rest of his long life, which was opposition to positivism, as well as all other liberal forms of law.

Schmitt volunteered, but due to an injury, served in a non-combat capacity in Berlin. Here Schmitt associated not with the Prussian elite, but with a more bohemian crowd.

After the war and the post-war revolutionary disturbances, the mainline left-center parties, over the objections of the defeated rightists and cutting out the violent Left, promulgated the Weimar constitution, in August of 1919.

This document governed Germany until 1933, and it was ultimately the springboard for the most important of Schmitt’s thought. But Schmitt’s first major work was not on the new constitution; it was a book about aesthetics as related to politics, Political Romanticism.

Here, he attacked the German Romantics for refusal to politically commit, instead remaining detached observers of critical events, manipulating words to create emotional effect while standing back from history. They would not decide what was worth fighting for; they merely engaged in “endless conversation,” all talk, no action.

As Balakrishnan notes, this book is neither Left nor Right, and one cannot tell where on the political spectrum the author fell, though Romanticism was generally associated with the Right. Schmitt even cited Karl Marx to support his arguments. He thus, at this point, had very little in common with the anti-Weimar Conservative Revolutionaries, men such as Arthur Moeller van den Bruck or Ernst Jünger. Not that he was a man of the Left; he was merely hard to classify.

Declining to work in government, Schmitt began his academic career in Munich, and in 1921 published The Dictator. Though the book was written earlier, 1921 was immediately after the various Communist revolts, as well as the Kapp Putsch; the political situation was, to say the least, still unsettled.

Article 48 of the new Weimar Constitution allowed the new office of President to rule by decree, using the army, in order to ensure “public safety,” a provision that assumed immense importance later.

Even though he mentioned this power, The Dictator wasn’t narrowly focused on Weimar; it was an analysis of all emergency power itself, and its use in the gaps that existed even under a system of legal positivism, where gaps were supposed to not exist.

Schmitt maintained that dictatorial power of some sort was essential in a political system, but distinguished between “commissarial dictatorship,” used to defend the existing constitutional order through temporary suspension (with the classic example of the Roman dictator), and “sovereign dictatorship,” a body or person acting to dissolve the old constitution and create a new one, in the name of, or on behalf of, the people as a whole.

The commissarial dictator has no power to change the structures or order of the state, which remained unchanged and in a sense unsullied by the dictator’s necessary actions; the sovereign dictator does have such power.

This had obvious applications to Weimar, but Schmitt did not focus on the modern; instead, his analysis revolved around sixteenth-century France, where the King claimed the right to suspend customary right in the execution of royal justice.

Opposed to the King were the Monarchomachs, part of a long tradition of political philosophy holding that a tyrannical or impious king could justly be overthrown, and that no extraordinary measures could be taken by the king without tyranny.

In between was Jean Bodin, author of The Six Books of the Republic, who argued that the king could indeed overthrow customary law, but only in exceptional situations, and only to the extent he did not violate natural law as it ruled persons and property.

This view, endorsed by Schmitt, rejects Machiavelli’s instrumentalism, and holds that the dictator is he, of whatever origin, who executes a commissarial dictatorship, as opposed to a sovereign, one who claims the right to execute a sovereign dictatorship. In the modern context, though, for Schmitt, the sovereign dictatorship is not always illegitimate, because the old structures have imploded.

What was wrong for the King of France in the sixteenth century was right for the Germans in 1919. That is, through his analysis, Schmitt concluded that the Weimar Constitution was wholly legitimate, even though it was the result of a sovereign dictatorship, because the sovereign dictator, the provisional legislative power, the pouvoir constituent (the power that makes the constitution), existed for a defined term and then dissolved itself.

The resulting political problem, though, was that if a new constitution was promulgated in the name of the people, the people remained extant, as a separate point of reference, from which “emerges ever new forms, which it can at any time shatter, never limiting itself.”

This, combined with the revolutionary proletariat threatening civil society, created at least the conceptual need for quick elevation of a commissarial dictator, to deal with illegitimate revolutions, before the possible need for a sovereign dictator arose. Such was Cavaignac’s suppression of the Paris mob in 1848.

(It is no accident that Schmitt’s book, Dictatorship‘s subtitle, often omitted in mentions of it, is “From the Beginnings of the Modern Conception of Sovereignty to the Proletarian Class Struggle,” and Schmitt has much to say about internal Marxist debates of the time, another reason he is still read by the Left).

Schmitt viewed Article 48 as authorizing such a commissarial dictatorship—but under no circumstances authorizing a sovereign dictatorship, which had been foreclosed upon the promulgation of the new constitution, whatever external threats might still exist. Though that did not preclude, perhaps, another such moment, which, in fact, arrived soon enough.

As you can tell, The Enemy is in essence a sequential look at Schmitt’s written output, trying to fit each piece into the context of its immediate time, and with other pieces of Schmitt’s work. Balakrishnan next covers two short but influential books revolving around Roman Catholicism, Political Theology and Roman Catholicism and Political Form.

Although often Schmitt is seen as a Catholic thinker, he had a tense relationship with the Church (not helped by his inability to get an annulment for his first marriage), and much of his thinking was more Gnostic than Catholic. While very different from each other, both books more clearly set out Schmitt’s views on how European decline could be stopped, and it was not by more liberalism.

Political Theology begins with one of Schmitt’s most famous lines: “Sovereign is he who decides on the emergency situation.” The book is an exploration of what the rule of law is, in real life, not in theory; an attack on legal positivism as Utopian through a presentation of the critical gaps that positivism could not address; and an explication of the actual practice of provisions like Article 48.

Someone must be in charge when it really matters, in the “state of emergency”; who is that to be? It is not decided, at its root, by positive law; deep down, it is a theological question (hence the title).

Turning from his earlier suggestion that only a commissarial dictatorship was typically necessary, Schmitt came closer to endorsing sovereign dictatorship of an individual, not derived from the people, in opposition to the menace of proletarian revolution.

He praised another anti-proletarian of 1848, the obscure Spaniard Juan Donoso Cortes, who saw “reactionary adventurers heading regimes no longer sanctioned by tradition,” such as Napoleon, as the men who would fight back atheism and Communism, until the earthly eschaton would restore traditional rule.

This vision did not entrance Schmitt for long; it smacked too much of restorationism, of trying to turn back the clock, rather than creating a new thing informed by the old. Still, this was and is one of Schmitt’s most influential books.

Less influential, perhaps, but more interesting to me, is Roman Catholicism and Political Form. Schmitt had fairly close ties to the Catholic Center Party, but this book is not a political work. Nor is it a book of natural law; as Balakrishnan says, in it “names like Augustine and Aquinas are nowhere to be found.

His portrayal of the political identity of the Church was a cocktail of themes from Dostoevsky, Léon Bloy, Georges Sorel and Charles Maurras.” A diverse group, that.

The book portrayed the Roman Church as the potential pivot around which liberalism and aggressively sovereign monarchs of the old regimes could be brought together, through its role in myth and in standing above and apart from the contending classes, as well as being representative of all classes and peoples. (It sounds like this book has a lot in common with a current fascination of some on the American right, Catholic integralism, a topic I am going to take up soon).

What the people thought didn’t matter, but they should be represented and guided, in their own interests, by a combination of aristocrats and clerics, presumably.

Both these books, and for that matter all of Schmitt’s thought, saw modernity as a mistake, however characterized: as bourgeois capitalism, liberal democracy, or what have you. Spiritually arid, divisive, atomizing, impractical, and narrow, it had no future; the question was what future Europe was to have instead.

In 1923 Germany, it certainly seemed that things were about to fall apart, which called forth Schmitt’s next work, translated as The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (though as Balakrishnan points out, and I have enough German to have noticed first myself, a better translation of the title is The Spiritual-Historical Situation of Today’s Parliamentarianism; the word “crisis” is not in the original title).

Here Schmitt lurched away from the idea of the sovereign imposing good government on the masses, and focused on the mass, the mobilization of the multitude that can give authority to the sovereign who decides on the state of exception, citing men like the violent French syndicalist Georges Sorel and impressing on the reader the power of political myth, rather than Roman Catholic truth.

Schmitt discussed the tension between liberalism and democracy, among other things focusing on rational discourse as the key to any parliamentary system, and that rational discourse tends to be lacking in proportion to the amount of direct democracy in a system, though Schmitt attributed that to the power of political myths creating political unity, not to the ignorance and credulity of the masses, as I would.

(This was once something that was universally recognized and assumed, but today the divide between rationality and democracy is ignored. This change, or debasement, derives from a combination of political ideology, in part informed by Marxism and cultural Marxism, and ignorance, from the forgetting of history and thousands of years of applied political thought. It will not end well).

Schmitt is not recommending a particular resolution or political program; Balakrishnan attributes that to Schmitt still building his own thought, without an ideological goal in mind.

To this extent, as I say, Schmitt is the correct type of reactionary: a man who sees what is wrong about today, and what is right about the past, and seeks to harmonize the two to create a better, but not Utopian, future.

Various other writings followed, responsive to the events of the 1920s. Among many interesting points, Balakrishnan notes that “Schmitt rejected what would later be called ‘Atlanticism’: the idea that the USA and Western Europe belonged to a common civilization, and thus shared political interests.”

(In the years after World War II this was a particular focus of Schmitt, giving him something in common with the later French New Right, as well as the Left in general).

He also mocked the League of Nations; if what matters is who is sovereign, international “law” is the final proof of the contempt in which positivism should be held. He wrote a massive work on German constitutional law (which is untranslated to English), analyzing the relationship between democracy and the Rechtstaat, the core structures of German law revolving around the rule of law, which did not presuppose any particular form of government.

In these writings, Schmitt addressed a wide range of thorny problems, including the legitimacy of law and who authorizes a new constitution, from which arise questions of legitimacy, and, just as importantly (and about to become more important at that time), questions of whose interpretation commands assent.

This latter set of questions began to crystallize Schmitt’s adherence to “decisionism”—the idea that what matters, above all, to the legitimacy of a decision is not its content, or its tie to some underlying document or system, but that it be made by a legitimate authority. This is, needless to say, directly contrary to the claims of legal positivism.

As German politics moved toward its climax, Schmitt’s next work was more theoretical, The Concept of the Political (first published in 1927, then substantially revised in 1932, in part as the result of correspondence with Leo Strauss). This book sounds like the most relevant to today, both in its topic and in the specifics it diagnoses about modern liberalism.

Its overarching theme is the most famous of Schmitt tropes: the enemy. While, like all Schmitt’s works, this book is complex, its premise is that “the concept of the state presupposes the concept of the political,” and what ultimately defines the political is the opposition between friend and enemy—not, as Balakrishnan notes, private friends and enemies, but political communities opposed to each other.

Politics is thus, at its core, not separate from the rest of life, but, ultimately, the way in which a political community determines its destiny, in opposition to those who hold incompatible beliefs, through violent conflict if necessary. This is an internal decision to each political community, not susceptible to rational discussion with those outside the community, and it is not a moral, but rather a practical, decision.

Liberalism, which believes that politics is a matter of pure rationality with a moral overlay, not only misses the point, but by being wrong, exacerbates the chances of and costs of conflict, especially by turning all conflict into a crusade where the enemy is evil, rather than just different. Liberalism makes war and death more, rather than less, likely…

“Schmitt claimed that the logic of these decisions cannot be grasped from a non-partisan perspective. The point he was making was directed at those who, failing to understand the irreducibly partisan, emergent dynamics of such scenarios, see the causes of major political events in the small tricks and mistakes of individuals. Lenin, he said, understood that such people must be decisively refuted.”

In fact, conflicts which seem irrational after the fact are not at all irrational; we just cannot, if we ever could, see clearly the rational impulses that drove them, which, again, boil down to the friend/enemy distinction.

In the late 1920s, Schmitt moved to Berlin, and became part of circles there, mostly conservative but idiosyncratically so. He became close friends with Johannes Popitz (later executed for his role in the Stauffenberg plot), who opened doors in government for Schmitt.

He wrote on various topics, including, interestingly, on technology, noting presciently “From its onset the twentieth century appears not only as the age of technology but as the age of religious belief in technology.”

He did not think this was a good thing; it created unrealistic expectations, especially among the masses, and encouraged belief in technocratic, “Fordist” government, a disaster in the making, because technology could never solve human problems, or eradicate the friend/enemy distinction that underlay all human political relations—but it could make war worse, and it “dissolved the protective atmosphere of traditional morality which had shielded society from the dangers of nihilism.”

In many places throughout his career, whatever his own religious beliefs, Schmitt was very clear that man needed the view of history as a struggle reaching toward redemption. The disappearance of that belief would destroy the enchantment of the world, but would not reduce conflict, which would be more and more meaningless.

That’s pretty much the state we’ve reached today; Schmitt would not be surprised, nor he would be surprised by the attempt to resolve this problem by seeking redemption through technology.

As the clock ticked down to National Socialism in power, Schmitt became more involved in government, especially in advocating various forms of constitutional interpretation. Among other works, he wrote Legality and Legitimacy, analyzing the tension between majority rule and the legitimacy of its decisions with respect to the minority, casting a jaundiced eye at the ability of liberals to resist Communists and Nazis.

At this point, in the early 1930s, he was anti-Nazi, but that changed as the Nazis came to power, and Schmitt (always keenly interested in his own career) saw on which side his bread was buttered, although he was also fascinated by the Nazis and what their rise said about politics and political conflict; moreover, he made the typical error of intellectuals, to believe that he could influence and control the powerful through his intelligence.

He ramped-up his own anti-Semitism and, infamously, publicly justified the Night of the Long Knives as “the leader protecting the law.” Even here, he was precise in an interesting way—although his purpose was “nakedly apologetic,” he objected to the retrospective legalization of the Röhm purge, holding that part of the role of the sovereign was, in extreme cases, to extra-legally implement actions dictated by the friend/enemy distinction.

Soon enough, though, despite his attempts to become ever more shrilly anti-Semitic (among other dubious offerings, suggesting that Jewish scholars referred to in books have an asterisk placed by their name to identify them as Jewish). But he was still viewed with suspicion by the Nazis, as a Catholic and an opportunist, and within a few years he was exiled from political life, before the war began.

He did not suffer worse consequences, in part because he was protected by Hermann Göring. Still, he kept writing, among other things, using Thomas Hobbes as a springboard, developing a theory of the supersession of nation states by larger blocs embracing satellite states, as well as related theories of the political implications of Land and Sea.

After the war, Schmitt refused to submit to any form of denazification, so although he was not prosecuted, he was barred from teaching for the rest of his life—another forty years. He maintained intellectual contacts with a wide circle, though, and remained somewhat influential—an influence that has increased since his death in 1985.

Most interesting to me in his later writings is Schmitt’s theory of the katechon. This concept is taken from 2 Thessalonians, which discusses the Antichrist, the Man of Sin, who, verse 6 tells us, is restrained or “withheld” by a mysterious force, the katechon.

When the katechon is withdrawn, Antichrist will become fully manifest. Saint Paul, however, implies that his listeners know who the katechon is. Schmitt expanded this into an idea that some authority must restrain chaos and maintain order, perhaps the Emperor in Saint Paul’s time, another force now—but not the popular will, certainly, and not any element of liberal government.

To grasp the importance of this idea to Schmitt, it helps to know that he once wrote (although this quote is not in Balakrishnan’s book), “The history of the world is like a ship careening aimlessly through the sea, manned by a bunch of drunken sailors who scream and dance until God thrusts the ship under the waves so there will be silence.” Schmitt wasn’t big on history having an arrow, a key claim of liberalism.

Into the idea of the katechon fit most of Schmitt’s prior ideas, including the commissarial dictator, the sovereign who decides on the state of exception, and the variations on Hobbes’s Leviathan that Schmitt explored.

That’s not to say that Schmitt was predicting the rise of Antichrist, or offering a religious concept, rather that the acknowledging the key role of a Restrainer embodies the central theme of much of his thought. I think one can, perhaps, contrast such a role with the role suggested by the Left, of some person or a vanguard, who creates a wholly new system, often conceived of as Utopian.

In reactionary thought, therefore, the katechon plays the essential role of being rooted in reality and human nature; the force that, through a combination of power and inertia, prevents the horrors unleased by Utopian ideology.

As can be seen from the title he chose, Balakrishnan sees the distinction, organically arising in every time and place without the will of anybody, between friend and enemy, as the key distinction of Schmitt’s thought.

In Schmitt’s own words, “Tell me who your enemy is and I will tell you who you are.” You only have to pull a little on this string to come to disturbing conclusions, though, about today’s America. If the premise is that at some point the members of a once-united nation can be split by a friend/enemy distinction, which is certainly objectively possible, the question only becomes how it can be determined if this has happened, and what to do then?

Certainly the American Left long since recognized, since it is the necessary belief of any ideological worldview seeking Utopian goals, who is friend and who is enemy. And even a casual listen to the words of the Left today, from their foot soldiers to their elites, reveals an explicit acknowledgement of this view.

It is not just ideological, either; the Left thrives on the solidarity that comes from recognizing who the enemy is. The American Right, on the other hand, is still delusionally trapped in the idea that we can all get along, or at least, their leaders hope to be eaten last.

Meanwhile the Left marches its columns ever deeper into enemy territory, stopping at nothing and only avoiding widespread violence (though, certainly, there is plenty of Left violence already) because it is not yet adequately opposed. All this fits precisely into Schmitt’s framework; the only surprise is the one-sided nature of the battle.

The Left’s approach is subtly different, perhaps, than the one Schmitt outlined, because the Left insists on politicizing literally everything, rather than only the key points of difference (although maybe that is simply required battle on all fronts, since their ideology presupposes no private sphere).

This spreading thin, driven by ideology, potentially erodes their power, or would if they were being opposed at all, more so if effectively. Beyond that, though, the fatal weakness, in Schmittian terms, of the American Left’s approach, is total lack of both any sovereign decision-maker or source of legitimacy for its decisions, even within a strictly intra-Left frame.

Perhaps this is a universal flaw of the ideological left, from the French Revolution on, and the source of the truism that Left revolutions eat their own. Without a sovereign, no stability, and no future—only the capacity for destruction, on full display now, after which those not poisoned by the beliefs of the Left pick up the pieces.

But first, they have to be recognized as enemies, and treated as such. No time like the present to begin, and better late than never. Certainly, a competent, disciplined leader on the Right could take Schmitt’s theories and weave a coherent plan of defense and attack. Instead, we get Donald Trump, who is better than nothing, but not by much. Don’t get depressed, though, since that Man of Destiny may be just over the horizon. 2019 will be soon enough.

Charles is a business owner and operator, in manufacturing, and a recovering big firm M&A lawyer. He runs the blog, The Worthy House.

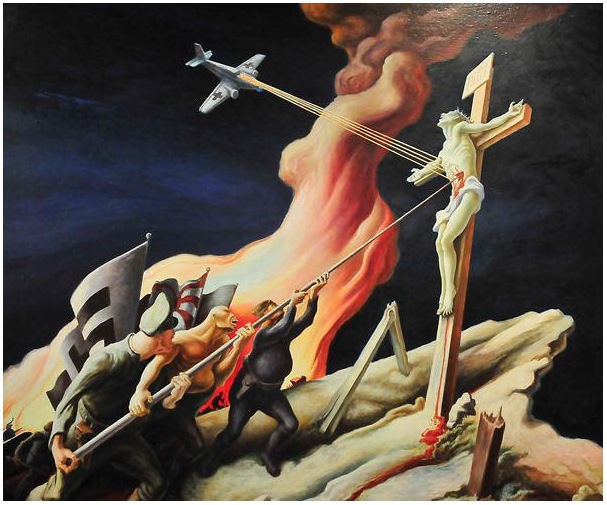

The photo shows, “Again,” by Thomas Hart Benton, painted in 1941.

Identity In Jesus

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched—this we proclaim concerning the Word of life. The life appeared; we have seen it and testify to it, and we proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and has appeared to us. We proclaim to you what we have seen and heard, so that you also may have fellowship with us. And our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son, Jesus Christ. We write this to make our joy complete. (I John 1: 1-4)

We live in a culture that is eager for religious experience without being too Christian.

In the United States of America over 80 per cent of the population believes in a God or gods that have power over the universe. When asked further; if all the worlds religions essentially prayed to the same God, 65 per cent of the adult public agreed.

In the Christian church among those who called themselves evangelicals, 46 per cent agreed and among those who labelled themselves as being ‘born again’ 48 per cent agreed that all of the worlds religions essentially prayed to the same God. This is quite astonishing.

Within the pews of American churches, two thirds of the people do not believe in the exclusive character of the Christian message, and almost half of all evangelicals say the same.

In light of these findings both inside and outside the church, who or what is our faith based on?

At the centre and core of our faith is the entrance of Jesus Christ into world history as the complete revelation of God. This is an event which happened in the town of Bethlehem over 2000 years ago.

It is an event that cannot be thrown away. It cannot be redefined as a myth or compared with the religious revelations offered by others such as Mohammed or Joseph Smith.

Throughout the world Christians are often tempted to forge new alliances in order to achieve noble ends. This is particularly true in countries where multiple faiths coexist side by side.

In the hills of the West Bank in Israel moderate Palestinian Muslims and Palestinian Christians have services in close proximity to one another and wonder what sort of unity they might build in order to construct a unified front for justice.

The same questions arise here in the West. There is difficulty when we find ourselves in interfaith dialogues that try to build unity particularly for commendable social and welfare programmes for; the homeless, or the fight against drugs and crime.

Chaplains in the services have to protect the distinctives of each faith tradition so that each worshipping community need not compromise what is essential to its beliefs.

Yet is it possible to conduct ourselves as Christians and exclude the place of Jesus Christ. Should we abstain from any such involvements?

If Christ is offensive to some, do we continue on in our ministry and deny the central event of our faith. Or do we hold fast to the scandal of what we affirm.

John who wrote this letter would say that there is no Christianity if Jesus Christ is not at the centre.

But perhaps there is another issue here for us; the more pressing question of whether it is appropriate for Christians to be silent about Jesus when meeting people of other faiths and persuasions. Roman Catholics, JW’s, humanists, Muslims.

When the time is right, when trust is secure, then the central theme of our faith, Jesus will be heard.

A college professor in a theological seminary in America chose this option recently when the University’s centre for Islamic Studies hosted a dialogue with a circle of invited Islamic leaders. Things went pear shaped when half way through; the Muslims politely dismissed themselves so that they could go out into the hall and pray towards Mecca.

The difficulty of course arises when that silence becomes no strategy at all; but a quiet concession to secularism, pc correctness, and tolerance. This is something we all need to carefully ponder.

The next question we need to consider is; should theological distinctives that is the really important parts; be set aside for the unity of the church?

Evangelical Christians often find themselves in main stream denominations or local congregations where adherence to particular orthodox doctrines brings tension. At what point does right and correct belief become more important than church unity? It’s a good question.

In June of this year The Presbyterian Church in Ireland (PCI) at their General Assembly in Belfast received criticism from people outside the church and from within, over their stance taken for those who are in same sex relationships.

The resolution passed by a clear majority; ‘those in a same sex relationship cannot be full members of the church. The children from same sex couples cannot be communicant members.’

These verses in John 1 tell us that any Christian who does not embrace the true reality Of Jesus Christ in world history, his teaching, and why he entered into the world; has departed hugely from the faith of the early church.

But someone might say what about the other issues that can cause difficulty among Christians and at the same time help to define Christian identity; like charismatic gifts, infant baptism, ordination of women, style of worship. Should the church sanction diversity within its ranks on these issues and others for the sake of a larger unity?

Whatever we make of these important points John would have our starting point with; Jesus. All these concerns and others are legitimate and important. But they are NOT central. They are not Biblical imperatives. John reminds us that the person of Jesus Christ the Word of Life is at the centre of our theological identity.

Sadly, many theologians and Christians enter into dialogue with those who uphold the trends of modern secular society. And what happens is that the church often loses sight of the larger question of Jesus Christ who straddles both the church and the world that he made. He is largely cast aside for a so called more tolerant approach. Although tolerance is usually one way.

This of course is nothing new. The identity of Jesus Christ is still the same scandal of Christianity that sets us apart from the world. Jesus is the one theme we cannot jettison, no matter what the benefit may seem, or what the temptation.

Which takes us to the third and final question. What does it mean to see, hear, touch, Jesus today? Can it happen?

John in his writing suggests that there will be a continuity of Jesus for all generations not just the first one.

In the fourth gospel John 14; Jesus promises that he will never leave his followers as ‘orphans’ and that those who love him and are obedient will become Christ’s new dwelling place.

In other words, John does not see Christ’s Ascension where he ascended into heaven as the termination of his presence among us. His spirit given to his followers is his own spirit. First John 3 says; ‘and this is how we know that he lives in us. We know it by the spirit he gave us.’

Is this a mystical experience or figment of the imagination running around inside our heads? No, John says that Jesus is real. We have heard, we have seen with our eyes, and our hands have touched him.

He goes to great lengths to let us know that Jesus is not a myth. John and his fellow disciples can say as witnesses that they lived with Jesus and studied him closely even touching him. They knew that Jesus was real not a phantom, not a vision, but God in human form.

John is at pains to try and convince us that Jesus is the Word of life and through him eternal life may be gained. If it wasn’t for people like John, Paul, Peter and others who committed their findings to paper for us to read in early manuscripts and later in the bible; possibly none of us would be here this morning.

John wants us his readers to hear this news because then we may have fellowship, both with him and with the Father and the Holy Spirit.

In effect John is a witness who testifies to these things. As we all know witnesses have a powerful effect on people. In a court of law for example the witnesses are key to a hearing.

If witnesses cannot be produced the case is often dropped. Hearing a story told by a person who was there holds much more weight than reading or hearing something second hand. It is why John is so keen for us to know that he was there, that he saw, and heard for himself.

We may not be first hand witnesses to Jesus life, death, and resurrection; but we can read from the first-hand accounts, and we are witnesses to what he continues to do in the world and in our lives today. He is still real and still alive.

Many I have no doubt can reflect on things that have happened in their own lives as a result of Jesus’s intervention.

Like the young lady who once prayed; ‘Lord, I am not going to pray for myself today. I am going to pray for others. But at the end of her prayers she added; and give my mother a handsome son in law’.

What about words from scripture that have spoken directly into my situation; a word that has helped reassure me about something; a word that has corrected my attitude. A word that has helped clear the clutter in my life.

A word that has guided me in a particular direction.

Jesus is the written word of the Bible and he is the one who lives out what is written here. He shows John and ourselves what this word looks like in reality. He is showing us what God is like in human flesh.

I have to say it’s a very good idea God came up with. I would never have dreamed up something like that.

What about reflecting on people getting Healed from sickness. The malady they had is no longer; and doctors can only conclude, I don’t understand this.

Or reflecting on lives of people that have been completely transformed. I was reading recently in the Gideon’s magazine of a former, 3 A’s person; she was angry, alcoholic, and an atheist. Now she is living for Christ with her demons behind her. How is this possible?

Or Angola; Angola is the name of the State penitentiary in Louisiana America. Its staggering to hear about what happened in that jail a number of years ago with the inmates and how hundreds of lives have been changed through the word of God.

One of the founders of Communism Karl Marx wrote; ‘the first requisite for the people’s happiness is the abolition of religion’………… John writes; ‘faith in Jesus Christ gives you a joy that can never be duplicated by the world.’ Two very different ideas of how we understand joy.

John simply but powerfully writes this letter to share Jesus with us and to testify that he has appeared as the word of life; to offer us fellowship, eternal life, and true joy.

Rev. Alan Wilson is a Presbyterian Minister in Northern Ireland, where he serves a large congregation, supported by his wife. Before he took up the call to serve Christ, he was in the Royal Ulster Constabulary for 30-years. He has two children and two grandchildren and enjoys soccer, gardening, zoology, politics and reading. He voted for Brexit in the hope that the stranglehold of Brussels might finally be broken. He welcomes any that might wish to correspond with him through the Contact Page of The Postil.

The photo shows, “Flevit super illam” (He wept over it), by Enrique Simonet, painted in 1892.

How Should We Read And Interpret The Bible?

How should one interpret the Bible? What rules should govern our exegesis? One approach is to tow the party line, a kind of exegetical “be true to your school” approach. This approach looks not primarily to the Biblical text itself, but to one’s ecclesiastical confession, and then reads what that confession says into the text.

For example, a Lutheran might approach the Biblical text of Romans through the confessional lens of the Augsburg Confession and conclude that Paul is there teaching justification by faith alone, exactly (and coincidentally) like Martin Luther would later teach.

Scholars today are unanimous that this is not an adequate or respectful way of dealing with Holy Scripture. Of course one believes what one’s church teaches and of course nothing like complete objectivity is possible. But one should nonetheless strive as best one can to set aside or at least turn down the volume of (say) the Augsburg Confession while one is exegeting the Biblical text and try to read the text on its own terms.

When reading Romans, one listens for the voice of St. Paul, not for the voice of Martin Luther. It is important to realize that “reading the text on its own terms” involves reading the text in its original cultural context. Thus one reads Romans knowing that it was written by a first-century Jew, not a sixteenth-century Catholic.

The task of turning down the volume of one’s confessional statements while exegeting the Bible is easy if one has no such confessional allegiance to those documents. The task is correspondingly difficult the more one gives one’s allegiance to those documents and confessions.

In the case of Orthodoxy, it can be difficult indeed, because our documents and confessions—the Church Fathers, or the consensus patrum—are the lens through which we read the Scriptures. This does not mean that we cannot or should not try to read the Scriptures on their own terms. It just means that for us the exegetical task is more complicated.

For some people, fidelity to the Fathers seems to mean effectively junking the idea of a scholarly reading the Scriptures in their original context and taking the “be true to your (patristic) school” approach. It is certainly an easy way to go. It saves one the work of investigating the cultural background in which the Scriptures were set and allows one to jump straight to the patristic conclusion.

I don’t need to determine how ancient Israelites would have read the text; I just need to read what St. Basil wrote (or perhaps Seraphim Rose’s take on what St. Basil wrote). But fidelity to the Fathers means more than simply agreeing with their exegetical conclusions.

It also means participating in their spirit and phronema, and reading the Scriptures with the same trembling respect that they did. It is this trembling respect that we bring to our exegesis when we insist on reading the Bible in its original cultural context.

Perhaps an example might be helpful. Take what is arguably one of the most famous lines in the Bible, “And God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness’” (Genesis 1:26). One asks, “Given the monotheism presupposed in the Book of Genesis, why the plurals? Why did God say, ‘Let us make man in our image’ rather than ‘Let me make man in my image?’ What do such plurals mean in the Old Testament?”

If we read Scripture on its own terms, we must begin by asking the question, “How would the original readers/ hearers of this passage have understood by it?” A refusal to ask this italicized question constitutes a refusal to situate the Scriptures in its own cultural context. It is true that for Christians this context cannot be the place we finish (Christ is where we finish, since He is the telos of the Law; Romans 10:4), but it must be the place from which we start.

As Orthodox in our exegesis we must end with Christ and the Fathers, but we cannot begin there. Exegetically we begin with the original hearers of the texts.

So, beginning in the time in which Genesis was written and read, we must ask, “How would the original readers of this text have understood the plurals? Are there any other times when God found Himself (as it were) not alone in heaven?”

There are indeed a few instances of such plural usage. In Isaiah 6:8, Isaiah “heard the voice of the Lord saying, ‘Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?’” (The Greek Septuagint was apparently a little embarrassed at the plural, for it rendered it, “Whom shall I send, and who will go to this people?”) Who was God addressing here? Was it simply that He was using what is called “the plural of majesty”, as Queen Elizabeth once did when she famously said, “We are not amused”?

We can begin to find an answer by looking at other passages in the Old Testament. In 1 Kings 22, the prophet Micaiah said that he “saw Yahweh sitting on this throne, and all the host of heaven standing beside him on his right hand and on his left, and Yahweh said, ‘Who will entice Ahab that he may go up and fall at Ramoth-gilead?’”

This reference to Yahweh’s divine council is reflected in other Old Testament passages as well. In Job 1:6 we read of the “sons of God” (i.e. the angels) coming to present themselves before Yahweh and Yahweh conversing with them, and in Job 38:7 we read of the sons of God cheering when He first made the world. These “sons of God” are exhorted to ascribe glory and strength to Yahweh in Psalm 29:1.

In Psalm 82:1 the Psalmist says that God has taken His place “in the congregation of God [Hebrew el], in the midst of the gods [Hebrew elohim] He holds judgment”. These “gods” (Hebrew elohim) were clearly His angels, the “sons of God” (Hebrew bene ha-elohim) Job 1:6. In Psalm 89:5-7, we read the same thing: “Let the heavens praise Your wonders, O Yahweh, Your faithfulness in the assembly of the holy ones! For who in the sky can be compared to Yahweh? Who among the sons of gods [Hebrew bene elim] is like Yahweh, a God [Hebrew el] feared in the council of the holy ones?”

The idea that a god acted in council and concert with the other gods was common in Mesopotamia. What we have here in the Old Testament is the monotheistic transformation of that cultural commonplace. There is no other deity except Yahweh. His council consists not of fellow-deities, but simply of lesser beings, angels, “sons of gods”.

But the idea that the king always has his council, whether an earthly king or Yahweh the King of heaven, was assumed in both pagan Mesopotamia and monotheistic Israel. It seems clear that it was to this council that Yahweh spoke and referred when making momentous decisions, whether those decisions involved enticing Ahab, sending a prophet like Isaiah to Judah, or creating man in His own image.

The picture of the divine counsel offering input is anthropomorphic, to be sure, as are pictures of Yahweh baring His arm in the sight of the nations, rolling up His divine sleeves before working to redeem Israel (Isaiah 52:10). It constitutes more a cultural backdrop to Yahweh’s acts than it does Scripture’s main message. But it is just this cultural backdrop that we find in Genesis 1:26.

That is where we must begin our exegesis, for that is how the original hearers, long familiar with the concept of Yahweh addressing His council, would have heard it. But although we begin there, we do not end there. All the teaching of the Old Testament forms a pedagogical trajectory, for the Law was a pedagogue to bring us to Christ (Galatians 3:24).

Taught by our Trinitarian experience of the grace of Christ, we ask about the sensus plenior, the deeper hidden meaning of the text. Why did the Hebrew Scriptures preserve such images as God’s divine council, with the resultant use of plurals? Historically this was clearly a cultural vestige of the common Middle Eastern picture of deity. But prophetically it serves as a foreshadowing of the tri-personal God.

The richness of reality that led the ancient authors to speak of a divine council (and in Israel to also use a plural name for God, viz. Elohim) would eventually find fulfillment in our understanding of God as Trinity. If one follows this trajectory of divine majesty it leads us in the end to the insights of the Fathers—in other words, it leads us to Christ.

The ancient instinct was that Yahweh was too great, powerful, and transcendent to be a solitary Monad in the Middle Eastern sky. Just as a king must have his council to be a true king, so Yahweh was too glorious not to be attended by the council of His holy ones. This is why the Old Testament texts spoke of other gods (Hebrew elim) even when they asserted Yahweh’s unique monotheistic status. And this instinct was not wrong.

Later on we discovered that God is indeed too great, powerful, and transcendent to be a solitary Monad. He was Trinity, bursting the bonds of solitary personhood in the effulgence of tri-personal deity. And the roots of this concept found initial and faint adumbration in those Old Testament plurals, as well as in the mysterious references to “the angel of Yahweh”.

One need not therefore toe the party line and shrink from reading the Old Testament in its cultural context. Such a cultural reading is not preferring “Jewish interpretations” to Christian ones as some might think. It is only recognizing that Judaism came before Christianity and the Old Testament before the New.

It is also preferring scholarship to partisanship, for the scholars who recognize that the plurals of Genesis 1:26 refer to Yahweh’s divine council are Christians (e.g. John Walton who teaches at Wheaton, and the authors of the Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible). It might be a Jewish interpretation if we stopped in the Old Testament and refused to see that interpretation as one stage in a trajectory that leads ultimately to Christ or denied the Holy Trinity.

But in fact we do not stop there, but go on from the Old Testament interpretation to find the richer sensus plenior in all the Old Testament. This fuller meaning of the text, so well expressed by the Fathers, is its highest meaning, and that which is of most use to us in our walk with God.

In this sense we must begin with the Fathers, in that they reveal Scriptures fullest meaning and the destination to which the Old Testament trajectories are leading.

But the highest does not stand without the lowest, and we must first understand the Old Testament as the message of God to Israel before we can understand it as the message of God to His Church.

If we insist on beginning at the end of our exegetical journey and confuse the sensus plenior for the original sensus, we are poor scholars and show unintentional disrespect for the Scriptures. Exegetical anachronism is not the way to go. If the Fathers teach us anything, they teach us that we must hear what the Scriptures have to say and that we must read them on our knees.

Fr. Lawrence Farley serves as pastor of St. Herman’s Orthodox Church in Langley, British Columbia, Canada. He is also author of the Orthodox Bible Companion Series along with a number of other publications.

The photo shows, “The Magdalene Reading,” by Rogier van der Weyden, painted before 1438.

Do We Still Have Enemies, Part III

III. Material Conditions of the Media

So, if “we” still have an enemy it is not those who challenge our cultures, for only in opposition to them do our groups have any meaning. Instead one must come to recognise that it is only through the group’s positive attributes, namely material conditions, that one can finds the true definition of who “we” are and therefore who our enemies are.

Thus, what truly endangers a group is not cultural outsiders, but those who deny the reality of material conditions as defining the group and see to hide it from us through a media-based ideology.

It was Marx who wrote in German Ideology “in all ideology men and their relations appear upside down, as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life process as the reversal of objects on the retina does from their directly physical life process” It can still be true to say that media is the domain of dispute even if the target of the cultural weapons that the media produces are not the true enemies of the exclusive “we”.

If as Marx suggested, the “superstructures” of every person’s life are defined by the “infrastructure” to which they are exposed then one starts to realise then the true division which exists in our society is not the one defined by cultures, for that is a symbiotic division, instead it is a division which runs along the lines of media infrastructure.

Effectively there are two tactics which can be adopted by the media in the liberal order to distract the exclusive “we” from realising who the true enemy is.

The first is to distract us from the truth by creating an illusionary enemy. The media/culture industry does this through a variety of means but draws strongly always on the idea of the cultural enemy to distract us. Social media in particular endlessly presents the Muslim, the black man, the person of another political orientation as being the enemy.

What has become popularly described as fake news, feeds people disinformation which says that a group with some different culture is the fundamental enemy of the group, without needing to say it explicitly. Although as has already been demonstrated they are needed for other cultural groups to have meaning.

But then the second, perhaps far more insidious method, is that in admitting that the enemy on the screen is an illusion to promote the idea that there is no struggle at all, that there are no enemies to fight against. To tell those people who try to fight against an enemy then they are ill, just as Nietzsche predicted of the last men.

But quickly, one realises that there is a whole industry of media production which supports every step of the process and who are interested in making people believe that they are one of millions, if not billions of universally alike consumers without an enemy, so as to keep providing you with the illusion of catharsis in the false enemy.

Marx identified religion as the central ideology of his time which was both false and a weapon of the oppressors to the proletariat in their place. It does not seem unreasonable to propose that it is now the media which is the new ideology designed to make all believe that they are consumers when in fact they still face the same class struggle, defined by the material conditions of their lives as they always did.

Thus, what one comes to realise is that the true enemy is not someone facing the same struggle within a different culture. What one comes to realise is that in our age it is not a person, but a system of things populated by certain people. No longer does one exist in a proletariat-bourgeoisie or serf-master dichotomy, but rather one exists against a system of thing.

As Marcuse wrote “the society which … undertakes the technological transformation of nature alters the base of domination by gradually replacing personal dependence … with dependence on the objective order of things”

Every time one clicks on a YouTube clip, or uses Facebook, or Twitter, or Netflix “we” are giving ourselves over to an economic enemy which is exploiting us by stealth, by dominating our leisure time and creating a false sense of dependency on a media system. The enemy therefore is not an individual or group of individuals, but it is the system as a whole which has created at ideology which fundamentally undermines the value of truth by telling us that there are no enemies.

However, there are some who profit by that system and others who are exploited by it and therefore we are not all universal consumers. It is still the case that some of us are exploited and other exploiters (even if only unconsciously) and therefore “we” are not everyone.

When all is considered in tandem it becomes evident that we still have enemies although they may now appear in a different light and in a different domain. It is now media, which as the principal weapon of the system of economic oppression and which now forms the central locus for the struggle. It may for the moment appear to many that media forms some neutral space, but even now the veil is beginning to fall off from that false ideology.

As Carl Schmitt said “the newly won neutral domain has become immediately another arena of struggle” To respond a little more directly to the research question posed at the start of this essay, the fact of this ideological lie of universalism which emanates from the media industry and the exploitation committed by the media industry means that there is not an identifiable “neutral domain” at this time, that “we” are not everyone and that therefore we still have enemies.

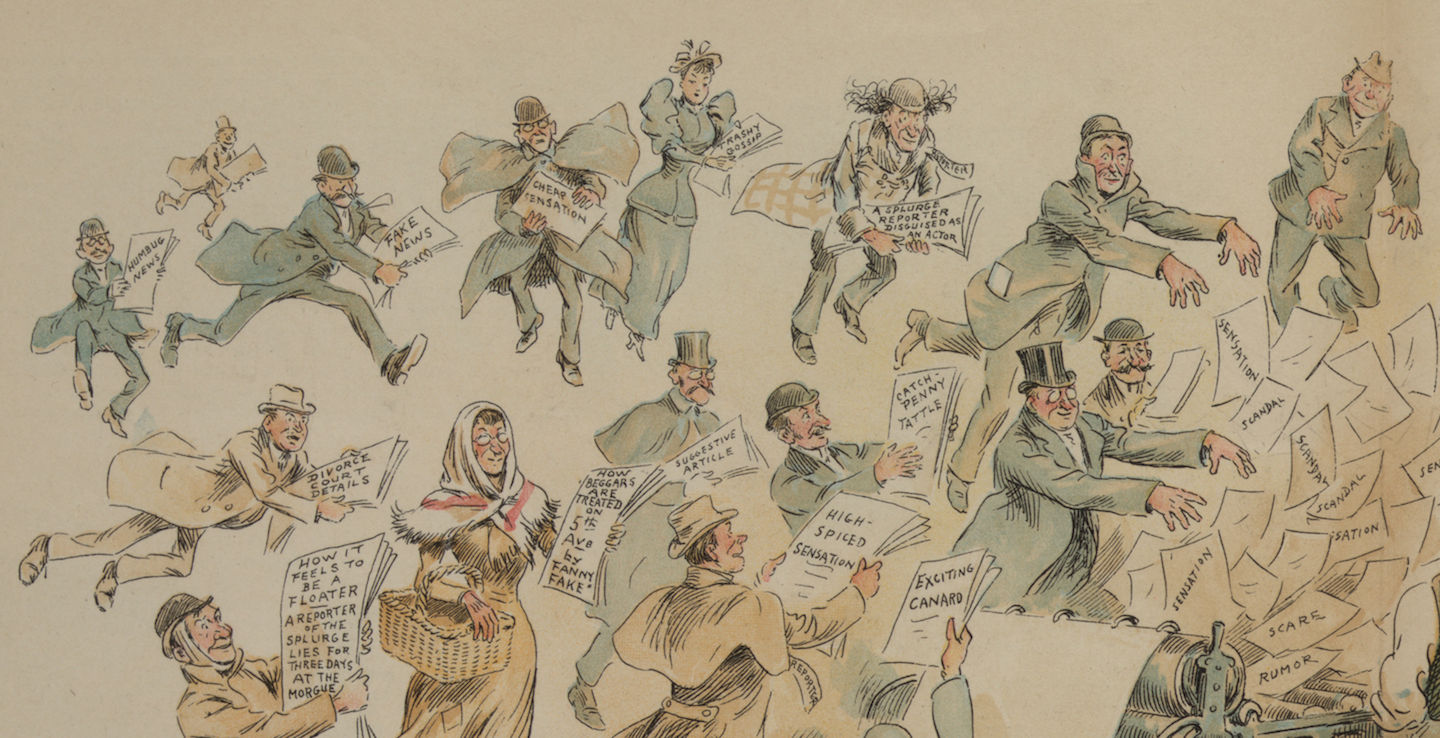

The photo shows a detail from “The fin de siècle newspaper proprietor,” an illustration by Frederick Burr Opper, printed March 7, 1894. Notice the term, “fake news.”

The Virtue Of Tolerance

He hath forsaken his covert as the lion,

for the land is laid waste because of the wrath of the dove,

and because of the fierce anger of the Lord.

(Jeremiah 25:38)

What does it mean to be tolerant? What makes tolerance virtuous? Indifference? Not caring about what others think? Jaded apathy to the world? Of course, not.

True tolerance is not passive heartlessness; it is the patient suffering of wrongs for the sake of justice. What is the key difference between callous indifference and the virtue of tolerance? Tolerance requires a code of ethics; the knowledge of right and wrong. Indifference knows neither good nor evil.

For example, if I am indifferent to violence, then I don’t care about the abuse of those around me. I don’t desire to change their behavior (Why would I try change the world if I didn’t care about it, and I felt it couldn’t affect me?).

Perhaps I don’t care about the violence around me because I don’t know of its existence. Or, I don’t know because I just don’t care. Afterall, isn’t apathy the greatest ally of ignorance? The two deserve each other.

But where are the tolerant? Where do they stand in the face of violence?

Those who truly tolerate violence are not passively indifferent to its horror. They’ve lost the right to be blissfully ignorant; they’ve made the fall. They, more than anyone else, know the sins of the world. Why? Because they suffer through them every day. True tolerance – like love – is suffering.

The original meaning of the word, “suffer” was “to permit,” “to allow,” or “let” (as in those famous words of Christ, “Suffer little children to come unto me,” in the King James translation of this passage from Luke 18:16. This original meaning was replaced in the seventeenth-century by the current understanding of “suffering” – to undergo pain or cruelty.

Blind eyes and deaf ears are the broken satellites of the wicked heart; but the tolerant cannot look away.

But what good is there in just looking on? Doing nothing is exhausting after all. What are they tolerant waiting for? Justice? Reason? Love? God? All of these are just another word for salvation I suppose, but who’s being saved?

Maybe the tolerant suffer for the sake of something greater than themselves. In the Crito, Socrates suffered the injustice of his trial – not because he was indifferent to injustice – but because he believed his suffering was a small price for the preservation of a just and law-abiding society.

It’s quite possible that the tolerant seek to be saved. But from who? Why themselves of course! Is there a greater enemy? As Nietzsche warned “fight not with monsters lest ye become a monster; for if one gazes into the abyss, the abyss gazes back into you.”

But let us stop to consider the possibility that the truly tolerant suffer for the sake of those who trouble them. Parents, teachers, and lovers are too familiar with patently suffering for the sake of others in the hopes that they’ll change.

It’s important to say that you don’t tolerate the entirety of the one you love, rather you tolerate the sins of the one you love. Could you imagine if a husband asked his wife “Do you love me?” and the wife responded “Well… I tolerate every part of your totality and suffer through your very presence.” That’s not love – that’s a stockade.

Someone who loves you doesn’t tolerate you so much as they tolerate your defects – because hopefully there’s more to you than that.

But those who love others do tolerate the unsavory aspects of their nature, and that requires strength, patience, kindness, and the ability to look beyond the ugliness of the immediate. True beauty is found by tolerating skin-deep faults and seeing the transcendent aesthetics hidden in all things.

Why do we tolerate the ones we love? Because it gives the other a chance to be reconciled; it is the path of forgiveness. Tolerance gives the unreasonable the chance to see reason; the hateful a chance to love by being loved.

When we are intolerant of the trespasses of others, we cast the abysmal around us into further darkness. But when we show tolerance through the open arms of hospitality or in the guidance of a helping hand, then we offer the stability that the other so desperately lacks.

But is tolerance practical? Why not force people to cut off their offense’s cold turkey? I tell you now that nothing is more impractical than a firm belief in the draconian.

The word, draconian, comes from the story of the Athenian lawgiver Dracon, a ruler who assigned the death penalty as a punishment for most of the minor offenses committed by the citizenry. Plutarch writes how “Dracon himself, when asked why he had fixed the punishment of death for most offences, answered that he considered these lesser crimes to deserve it, and he had no greater punishment for more important ones.”

The idea that one can remedy the offenses of a society through intolerance is not a novel idea. Did it work? What became of Dracon? He was exiled and his laws were immediately repealed!

What renders the draconian state a useless enterprise? That fact that the state does not, should not, and more importantly cannot control everything that happens among the citizenry. Most of the economic, political, social, intellectual, and cultural decision-making has always existed in the hands of the citizenry. The unwritten laws and social norms of the people has always outnumbered and outweighed the written laws of the state in both power and magnitude.

Thus, when someone uses hard-power to force reformation instead of tolerating the growing pains connected with the mobilization of soft-power and liberality, the result is most always tyranny.

History shows time and time again that “getting tough on crime” is nothing more than a myth for fake news to print and saber-rattling demagogues to howl.

Want to end homelessness? Then show tolerance by sharing what you have, not hunting those who have nothing.

Want to end drug addiction? Then show tolerance by providing users with needles and clean doses.

Want to end alcoholism? Show tolerance by providing a space where people can get a drink and talk about their addiction.

Want to end hate speech? Then tolerate it through free speech because you’ll never end racism, homophobia, and sexism through coerced speech, or speech that must conform. We’ve tried it before, and it never works.

Want to end barbarism? Show tolerance through civility.

Want to end intolerance and hate? Show tolerance and love even if it kills you.

As the Christian apologist Tertullian writes, “That’s why you can’t just exterminate us; the more you kill the more we are. The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church. Your praise those who endured pain and death – so long as they aren’t Christians! Your cruelties merely prove our innocence of the crimes you charge against us … And you frustrate your purpose. Because those who see us die wonder why we do, for we die like men you revere, not like slaves or criminals. And as they find out, they join us.”

Tolerance is the heart that beats on in a world of heartless indifference.

The photo shows, “The Return of the Prodigal Son,” by Nikolay Losev, painted in 1882.

The Godless New Man

Development of a new concept of the family is actively underway. This process is covert and insidious. With an ever-increasing frequency, we hear such terms as “encouraging positive parenting”, “improving parental competences”, “changing parenting styles” and “combating gender stereotypes”.

What do they mean? Where do all these terms come from? Are they coined by benevolent people sincerely interested in improving family education? Or do they simply promote the ideas of some interest groups whose intentions have nothing to do with upholding traditional family values? Walking in the thickening fog that blurs our vision and clouds our already preoccupied minds, how can we decipher what these phrases actually mean?