The death of the free market at the hands of monopoly has gotten a lot of recent attention. By far the best book about this problem is Tim Wu’s The Curse of Bigness, which through a “neo-Brandeisian” lens focuses on how monopoly destroys the core frameworks of a free society.

This book, The Myth of Capitalism, comes to much the same conclusion from a more visceral starting place—why have wages stagnated even though the labor market is tight and corporate profits are soaring? The answer is corporate concentration, and Jonathan Tepper is, like Wu, offering concrete solutions.

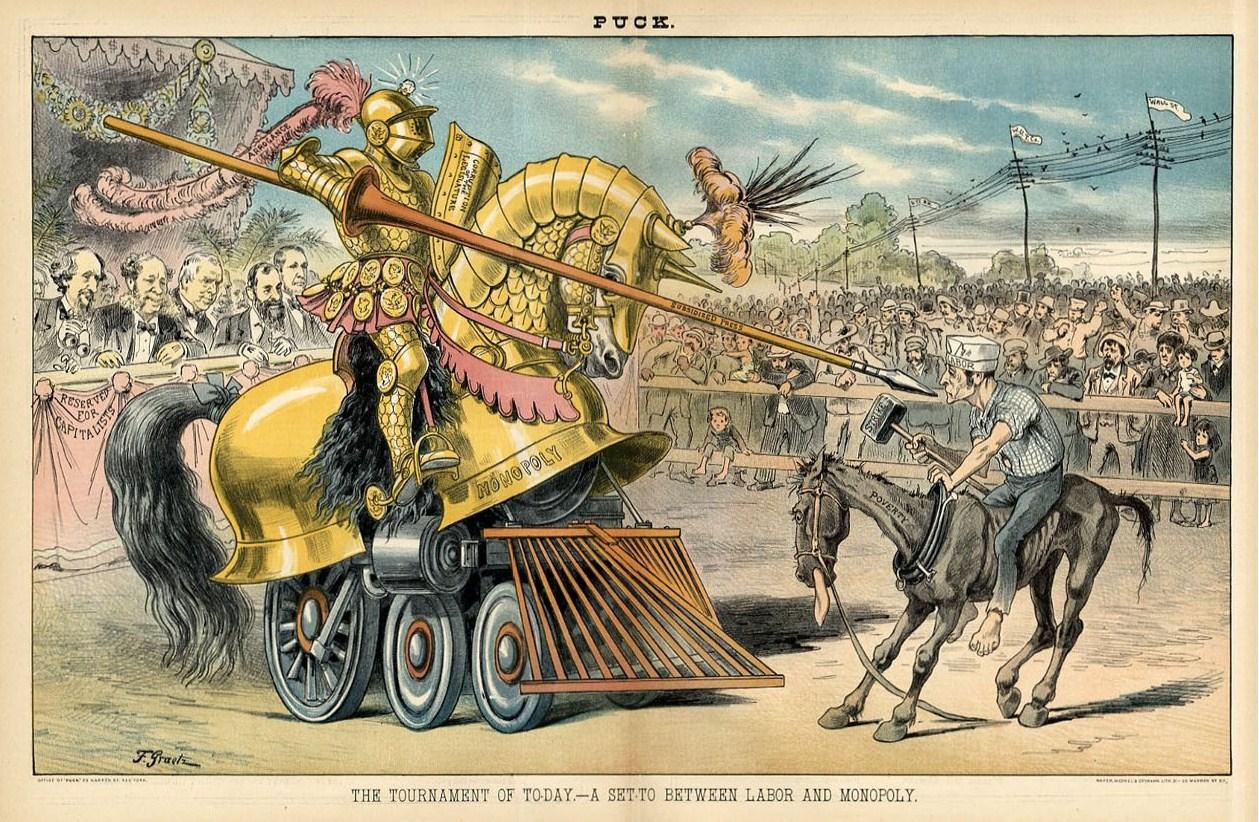

The problems that monopoly causes are not disputed in any relevant way by anyone but a few University of Chicago ideologues. The difficulty is that all possible solutions are opposed by the ultra-powerful, ranked in armed array.

One traditional way of dealing with such concentrations of power is populism, of the Left or Right. On a good day, we get Theodore Roosevelt; on a bad day, someone less attractive. It is therefore no surprise we see populist realignments arising across the political spectrum, with both conservatives and liberals girding for battle against the neoliberal kingmakers who dominate the Republican and Democratic parties. The question is whether the populists have enough will to start, then finish, the fight. As Warren Zevon sang, “Some have the speed and the right combinations / If you can’t take the punches, it don’t mean a thing.”

If the new populists, the neo-Brandeisians, do have the will, this book offers some tools. It is less cerebral than Wu’s, aimed at people who have to be told who Leon Trotsky was (“a Marxist revolutionary,” if you’re curious). Tepper’s basic point is that we no longer have the free market (what he incorrectly calls “capitalism”), because most industries no longer have relevant competition.

It is not because of monopoly, which is usually very obvious, but rather the less noticeable oligopoly, where a handful of firms dominate but competition, to a casual observer, appears to exist. The inevitable result of oligopoly, as Tepper (along with what appears to be a co-author, Denise Hearn) shows and nobody who lives in the real world doubts, is tacit collusion on all fronts, pricing and otherwise, to avoid competition. In an oligopoly collusion is nearly as certain as death and taxes, even if done without any formal agreement.

Tepper demonstrates in several compelling ways that competition is dying. Mergers have reduced the number of firms in almost all industries, while antitrust enforcement has declined over the past four decades to nearly nothing. Since 1995, the word “competition” has declined by 75% in annual reports to shareholders of public companies.

Tepper offers a variety of technical measures to demonstrate his point, and I don’t think anyone disputes this. (If anyone does, I’ve missed it). He then lists an astonishing number of industries that are nearly totally consolidated (although someone should tell him that Purdue is the university and Perdue is the chicken company). Airlines and cable TV, obviously, but also beer, bacon (all those different brands in the store are owned by Smithfield), milk, eyeglasses, drug wholesalers, crop agriculture, and very much more.

Why is collusion to avoid competition bad? Tepper believes that oligopoly is literally destroying the country, and he’s pretty much right (though a lot of other unrelated things are simultaneously destroying the country). Obviously, everyone pays higher prices. But higher prices are the least of collusion’s evils.

The most evident problem for most people is that oligopolies, in Tepper’s words, killed your paycheck. Stagnant wages, the problem that sparked the writing of this book, lead to higher inequality, social tension, and societal destruction.

And a big cause of stagnant wages is corporate concentration, which directly lowers wages for workers, since oligopolies act as monopsonies (buyer price-setters) in the labor market, especially in smaller labor markets. It is not an answer to say that workers should go where the jobs are. The wages are often no higher there, and people are loathe to leave their communities and people, as they should be. (This is one of the key points of J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy).

It’s not just monopsony. Tepper also focuses on a particular burr that chafes me, non-compete agreements. These have exploded, and are commonly found now even in burger-flipping jobs. They are an abomination. (None of my employees, in any position, has to sign a non-competition agreement, on principle. I don’t care if my employees compete with me. Of course, I’m so wonderful to work for that nobody would ever quit).

Non-competition agreements are an offense against God and man, and it is not a coincidence that California has, for 150 years, forbidden them and developed Silicon Valley as a result. That rule should be extended nationwide, immediately, federalism be damned.

Beyond wage stagnation, lack of competition leads to lack of innovation. Again, this is a commonplace, known when the Sherman Act was passed (in 1890), but conveniently forgotten when the money flows to the right political pockets. Less competition means less investment in winning competitions.

Oligopoly also means that startups can be bought out with offers they can’t refuse, not dissimilar to Pablo Escobar’s famous demand to choose “plata o plomo.” And aside from buyouts, startups suffer direct attacks made possibly by the disproportionate power of oligopolists, such as Google’s suppression of, or theft of the data of, any type of business that might compete (not just in search, but in any type of data that Google thinks it can monetize).

Occasionally one hears the halfhearted response that we have monopoly or oligopoly because big companies provide what consumers want and do a better, more efficient job. Tepper, like Wu, sneers at this explanation. The reality is that most giant companies are actually less efficient; there is such a thing as diseconomies of scale.

Even back in the day, when Standard Oil was forcibly dismembered, the pieces collectively were more valuable than the monopoly. Again, nobody with any sense defends oligopoly; they just dodge or ignore attacks, and laugh all the way to the bank (Jamie Dimon’s bank, or another one of the oligopolist banks).

Covering all the bases, Tepper also criticizes common ownership cutting across publicly traded firms, noting that index fund investing has exacerbated the problem, since entities like Fidelity have large stakes in nearly every company, including those that are putatively competitors. He touches on the problems with CEO pay, too, which are covered in more detail in Steven Clifford’s The CEO Pay Machine, suggesting better alignment of incentives through workers being granted shares, restrictions on stock buybacks, and lockups on manager-held shares.

Government actively assists the process of oligopoly formation, and not just by failing to enforce the antitrust laws. Enforcement of those laws is corrupted by the ideology of Robert Bork and by highly compensated economists who spin fantasies of future consumer price reductions that never arrive.

On those rare occasions when the government attempts to enforce the laws, the courts side with the oligopolists (as in today’s decision by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, rejecting the Trump administration’s attempt to block Time Warner’s merger with AT&T, where, bizarrely, the burden of proof appears to have been put on the government).

For another example, Congress forbids the sale of insurance across state lines, effectively creating oligopolies; Obamacare, largely written by insurance companies, did not change that at all. And Congress, along with administrative agencies, eagerly obeys the commands of oligopolists to increase regulation.

That may seem odd, until you realize what many people miss, that big companies always favor any regulation that falls harder on smaller companies, both due to compliance costs and as barriers to entry, and moreover they often write the laws and rules specifically to favor themselves.

The classic example of this is Mattel, when found importing toys contaminated with lead paint, got a law passed that required expensive third-party lead testing for all toy sellers—except for themselves, who were allowed to do it cheaply internally. Or, to take another example, what penalty did Equifax pay for massively exposing consumer data due to incompetence? None, because if you’re big enough and spread enough gold around, the regulations don’t really apply to you.

Government action is even worse and has greater impact than it appears, because beyond simple inefficiency and inequality, many of these oligopolies now themselves exercise the powers of government. Tepper offers Progressive economist Robert Lee Hale’s definition of government: “There is government whenever one person or group can tell others what they must do and when those others have to obey or suffer a penalty.”

By that token, certainly, all the Lords of Tech, from Google to Facebook to Amazon, are government, as are, in their own spheres, all the other consolidated industries. (And, of course, often these companies impose penalties on those who do not toe the line on their political ideologies; it is not just business penalties that are at issue). We are not that far off the classic science fiction dystopia where corporations are the government, and can impose their will on all sectors of society.

If everyone not in the pocket of oligopolists agrees that corporate concentration is a problem, why isn’t anything being done about it? Silly rabbit, it’s because all the money and power is on the side of the oligopolies. All these companies spend huge sums lobbying, and it’s been shown they get massive returns on the dollars spent.

They lobby to prevent antitrust enforcement; Google was the second-biggest source of campaign contributions to Obama. They lobby to add regulations. But it’s also the revolving door, at every agency and every level of government, that means oligopolists get what they want. Google, a particular target of Tepper, is one of the biggest offenders, with hundreds of its employees shuttling back and forth into and out of the government, collecting money and power both coming and going.

So far, so bad. These companies also use their power in perniciously creative ways, some of which Tepper does not mention. For example, it is well known that Amazon is the major source of income for many smaller businesses (and plenty of larger ones) that sell on its platform, and uses the data it obtains about such sales to benefit itself and eliminate the profits for those businesses, increasing its own monopoly power.

I don’t sell through Amazon; I’m a contract manufacturer, and thus invisible to Amazon. But one day last year an Amazon functionary called me up. They asked us to develop a brand in our industry (in essence, food, which we put into containers) which would be sold on Amazon. We could set the prices; the proposed deal was that we’d both profit if we developed an attractive brand, since Amazon would push it and we’d make money on the sales.

I figured this was a scam, since I am cynical and think Jeff Bezos should be put in a ducking chair, but set up a conference call anyway with a team of Amazonians. After buttering me up, they glibly mentioned in passing that, among other standard boilerplate in the agreements they’d send me to sign, which were of course trivial (but not negotiable), there was an unimportant standard provision: that at any point Amazon could buy this entire new brand from me, lock, stock, and barrel, for the lesser of $10,000 or fees actually paid to lawyers to register trademarks.

But, they assured me, this was just so they could “help me if there were any legal challenges.” A total lie, of course. What they were, and are, doing is suckering people who, unlike me, are not former M&A lawyers, by, at no cost to Amazon, throwing up hundreds or thousands of brands; seeing which succeed; then stealing them from their creators, who eagerly sign documents without paying any attention, hoping to hit the big time. A small thing, perhaps, but indicative of a cheater’s mentality. Fifty lashes for Jeff Bezos at the whipping post in the town square!

Tepper offers a long list of excellent solutions. Vastly more aggressive antitrust enforcement, using bright-line numerical rules about corporate concentration. Slowing down the revolving door. Common carriage rules for internet platforms that sell third-party services (not only Net Neutrality, presumably, but also other services, such as Amazon’s selling platform).

Creating rules that reduce switching costs, such as portability of social media data. All these are good, though I’d go farther. For internet common carriers, I would include rules that forbid viewpoint discrimination. I’d break up all major tech companies, and probably break up almost all existing corporate concentrations. I’d totally forbid the revolving door. Regardless, I find nothing deficient in Tepper’s solutions.

But these are all egghead solutions from eggheads, vaporware in the ether. Billions of dollars are being raked in by the powerful, and then distributed to protect their interests. The oligopolists will never accept a single one of these solutions.

Tepper works as an advisor to hedge funds (it is no surprise that those particular concentrations of power, which are also extremely pernicious and often eagerly participate in creating and extending the problems identified in this book, receive a grand total of zero attacks in this book). He is lucky he does not work for a think tank or other vulnerable entity.

Google, for example, brutalized Anne-Marie Slaughter’s New America Foundation in 2017 when it dared to have on staff an academic team who suggested that more antitrust enforcement against Google might be a good idea. Attacking the oligopolists is like chasing a demonic greased pig—even if you catch him, he’ll probably wriggle out of your grasp, and if he can’t, he’ll kill you.

What’s the answer, other than pitchforks? (I’m all for the pitchforks.) Well, divide and conquer, probably. We should serially use Saul Alinsky’s Rule 13: “Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.”

This will probably have to be done at the intersection of two other unpredictable factors. First, some especially spectacular bad behavior by a target, which implies that the each sequential target will have to first identify itself. Second, action by ambitious politicians, probably of the Left but maybe of the Right, willing to use this as a signature issue.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez may be an economic illiterate, but she’s ambitious and self-promoting enough to take on such a task, and tough enough to ignore the pressure and attacks from the oligopolists. Bernie Sanders maybe, too, but he’s so old his heart probably can’t take the punches. This is a task for the young.

On the Right, I can’t think of anyone—Trump, of course, but he lacks the discipline and has shown a disinclination to actually act populist (thanks, Jared and Ivanka)! Marco Rubio and Mitt Romney aren’t going to do it. Maybe J. D. Vance, if he ever runs for office, but he strikes me as not nearly vicious or ambitious enough.

But with any luck, the problems themselves will call forth the problem solvers. History shows us that for every action, a reaction—though, unfortunately, often one with unintended side effects. Within reason, though, I’d happily risk the side effects to destroy the oligopolists.

Charles is a business owner and operator, in manufacturing, and a recovering big firm M&A lawyer. He runs the blog, The Worthy House.

The photo shows, “Puck & the Mechanical Knight – A Modern-Day David & Goliath,” a political cartoon from the later 19th-century.