What follows is a personal account. It should not be read as a general description of symptoms that are true for all people. Much of what happens during any infection depends on the condition of individual immune systems and pre-existing medical conditions – and there is also the fact the coronavirus, Covid19, or the Wuhan virus has forty known mutations (thus far). So, it is difficult to say how each individual body will react when infected.

I contracted the coronavirus at a doctor’s office, of all places, where there was far too much coughing, sneezing and wheezing going on, without any regard for public hygiene, such as, covering the mouth at least. I chose to write this article anonymously, because suddenly we live in precarious times, and I have no idea what the fallout of my account might be. People have become so wild-eyed. There is a lot of misinformation, panic and finger-pointing, where to go out in the public now is not only controlled, if not forbidden, but an act of distrust. People look at you with anger if you are not wearing a face-mask. But it no longer really matters where I got the virus, and I should have worn a face-mask. So, I just want to deal with the facts. This is what happened next.

The Process Of The Infection

On the first day, I grew very weak and feverish. So, I thought I should go and get myself tested. This was an entirely useless effort, especially given what it involved. To get a test, they shove a swab of sorts all the way up your nose – really far up the nose, so it really hurts. And the man doing the procedure seemed especially inept (another reason why I want to remain anonymous). I say the test was useless because it is not as if getting tested will mean getting a treatment that will cure what you are being tested for.

I think these tests are simply an effort to get an idea of the number of infections. And I now think they only serve to feed the hysteria. Given the procedure, I would suggest that you avoid the test and just stay home. Once the test was done, it came back positive, and I was advised to lock myself away at home until I got better – and then to wait for another fourteen days, before trying to venture out into a public place. In effect, I was placed under house-arrest (just like everyone else).

The first three days of infection consisted of a very painful throat and fever. It was not really a sore-throat, as such, which we have all experienced, which makes the throat feel raw, as if it has been badly scratched. Rather, what I experienced was extreme pain when swallowing. If I did not swallow, I did not feel any pain. It was as if a hand clamped down hard around my throat, whenever I tried to swallow. I can imagine how this might prove very dangerous for some.

As well, trying to speak meant that my throat constricted and I could only get out a few words before lapsing into a bad coughing fit – again, dangerous for those with compromised lungs. And when I coughed, I got nosebleeds (which I have never gotten belief). But I believe that these nosebleeds were the result of the injury I had received when I got the test done; they were not an effect of the virus. But I could be wrong. This condition persisted for five days, during which I slept a lot.

Then, something very strange happened on the sixth day. The sclerae (the whites) of my eyes turned a dark red, and my eyes hurt. I say strange, because it seemed that I was now showing the ophidian origins of the virus (given the Chinese penchant for eating snake-meat in the winter months (because said meat is supposed to be very “warming”). But, of course, there are other theories about the origins of this virus. My eyes also started to water a lot, and I could not look at strong light without feeling a burning in my eyes.

On the seventh day, the stranglehold on my throat suddenly grew weaker, and I felt that my body was finally beginning to fight back with some success! My eyes grew less red. The fever became low-grade. The cough remained.

Over the next three days, my throat recovered to what I would call normal, where I could swallow with only a very slight pain, and my eyes cleared up completely, although they still watered. The cough persisted, but the fever disappeared.

As of writing this account, I feel that I have regained normalcy (homeostasis). The cough is infrequent and my eyes water occasionally. It is simply my body clearing things up, it seems. And, such is my rather uneventful journey through coronavirus land. In my experience, then, it was nothing more than a flu.

I should mention that I did not take any medication, nor did I take any supplements. I just am not a pill-popper. I did, however, take some home-made cough syrup, which helped a lot with the cough. I simply let my body’s immune system take over.

So, what does all this mean? There are two takeaways. First, there is the virus itself and its pathology. Second, there is the coronavirus-panic. In other words, there is the reality of the virus – and then there is the construction of what I call, “the Coronavirus Narrative,” which is all about whipping up fear and hysteria. The one has little to do with the other.

Regarding the question of pathology, the coronavirus is nothing new, of course, as it has been known and documented and studied for quite some time. The version that I got is simply another form of the flu.

Now that I have gone through the experience, I can honestly say that I have had far worse bouts of the flu in years past. So, if you are a normal, healthy person, you will not die from the coronavirus. This is not the Black Death revisited, as it is being currently advertised. Get that fear out of your head. If you are healthy, and your lungs are in good shape, and you catch the virus, you will be feverish. Yes, it will hurt (as my throat did); and, yes, you will cough a lot. But you will not die from it. Your immune system will fight back and flush it out of your body.

As with any flu, the only people at risk will be those who have very weak immune systems, or who have lung conditions, or who have other pre-existing medical conditions, which would be exacerbated by any kind of infection. In other words, the same people who also die each and every year of the regular flu. Thus, for example, last year in the United States, 80,000 people died of the flu. Probably the same number will die this year as well. The only difference being that this year the cause of death will be a flu by the name of Covid19 – and that number will only feed the panic.

The Grand Coronavirus Narrative

Something very strange happened with this flu virus – suddenly it became the Grim Reaper. This portrayal is held together by three types of stories that are continually being told in the media – those that delve into the origins of the virus (its etiology); those that dictate personal and communal behavior; and those that seek to posit some sort of catharsis, through purification or expiation, by extolling a solitary existence.

Right from the beginning, the question of how this virus came to infect human beings was misty. Some said that its origins were natural, having jumped species from bats, snakes, or ant-eaters to humans (given the Chinese penchant to eat such creatures, especially in the winter months, for their “warming” qualities of such meat, according to Chinese alchemy, i.e., medicine). But others said that it was a bio-weapon that had somehow “escaped” from a lab and into humans. Many were the videos shown online of poor victims collapsed on to the streets, bleeding, and even shaking and flopping about. They were all said to be victims of this virus.

Next came the massive governmental efforts by the Chinese to contain the virus by way of forced confinement of the people of Wuhan and other cities, and the videos of streets being sprayed with something or other (presumably a disinfectant).

Then, came the accusations. The Chinese said it was indeed a bio-weapon, let loose by the US military. And there were already reports of nefarious Chinese agents stealing material from labs in the States and Canada – and even the arrest of a Harvard scientist for being on the payroll of the Chinese. We are all familiar with these facts, and they hardly bear repeating.

Then came the reaction, which was an effort to win control over the spread of the virus. This meant doing what China did and shutting down everything and promoting (and even enforcing) self-quarantine. Stay home. Come out only if you need to buy essentials. Only through massive government effort that purification (catharsis) can be affected.

And then there was the media, which was, and is still, having a field-day promoting the hysteria, with 24/7 coverage. The ceaseless fearmongering works really well because it is always presented without context (like the daily infection- and death-count), so that for most people, the world is indeed facing a massive die-out event, much like the Black Death and the Spanish Flu of 1918. None of this is true, of course, but that matters little, since well-constructed narratives have no need of truth.

People are scared. No one wants to die. But people die of all kinds of things over the course of every year. However, when death is wrapped up in the form a contagion that floats about in the air, ready to infect anyone – the fear becomes justifiable. But there is also something very strange about the numbers being thrown about, which are used to promote the fear. Those that began this fear now seem be having second thoughts. Here is a good analysis.

The Technocrats

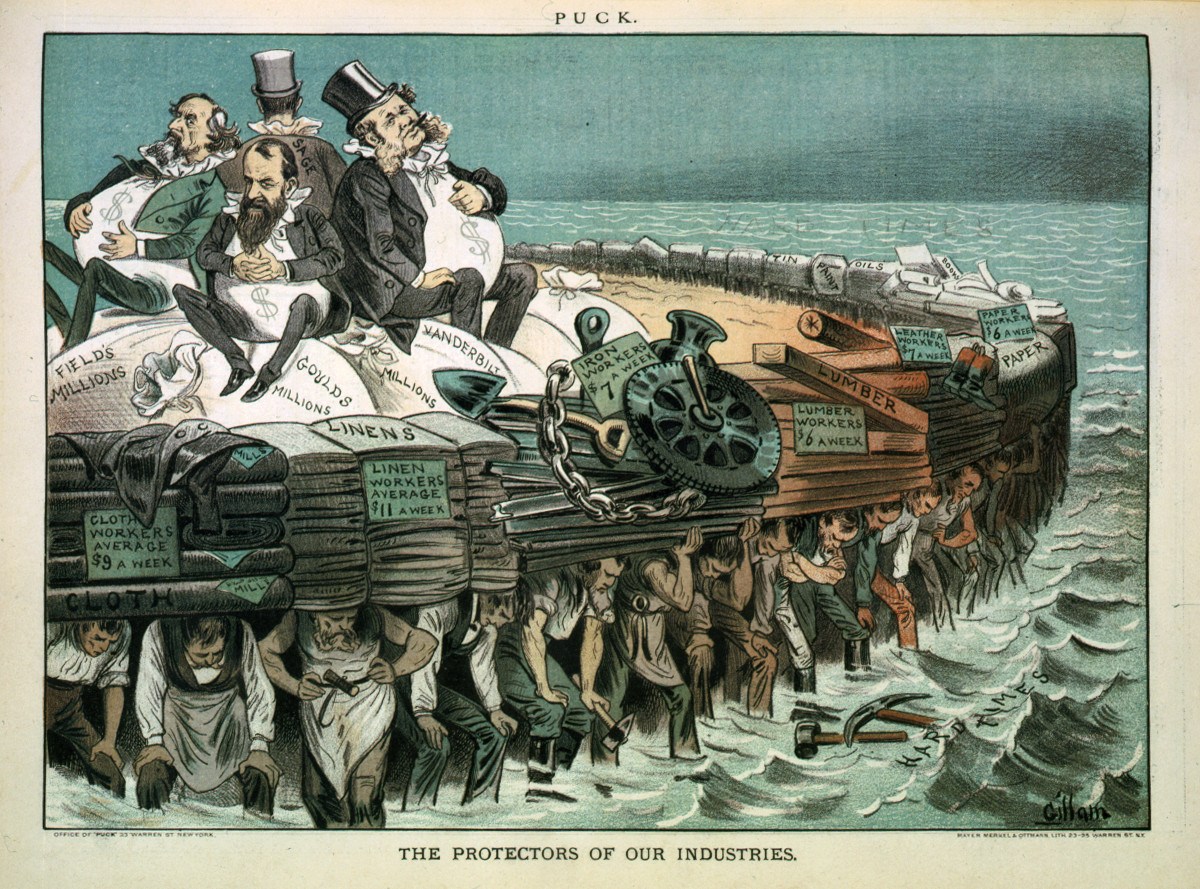

But this hysteria is also bringing back the fact of reality. One of the fundamental problems of modernity is that it is technocratic (in that it only relies on the opinions of experts, which then became all-powerful narrative that then guide us as to how we live and what we do). If experts agree, we have truth, and we must all kowtow to said truth (also known as scientific “consensus”). This has been the case with the promotion of environmentalism, genderism, politics, and now infectious disease. In effect, the purpose of science now is to continually affirm social narratives (which are happily manufactured by another set of experts – professors).

But the problem with experts is that they cannot be wrong, for they are purveyors of a new “gospel.” This means that all experts prefer to present extreme conclusions, rather than anything sensible. This is especially true of any sort of statistics that have to do with disease, where they are often as extreme as possible, because no one will blame them for being “cautious” – that less people died than they had predicted. If they low-ball their figures and the disease produces a higher body count, then they will be pilloried. So, these experts are always hedging their bets and safeguarding their reputations as well as their very lucrative careers.

And then there are the predictive models that they use to tell us how many will get infected and how many will die. As we all know – there are always problems with hypothetical mathematical models. Remember, the same sort of models that are giving us death-charts, have long been used to prop up the entire “Global Warming Narrative.”

Some Side-Effects

But suddenly, the Coronavirus Narrative has sidelined, even derailed, all other narratives that had kept so many busy for so very long. Does anyone still want to go and agitate for bathroom rights for transgenders? How about marching for feminism? Global warming anyone? What of the New Green Deal for a happier proletariat?

And all those mealy-mouthed moralists, who were busy squawking about “racism” and “xenophobia” – now have to be xenophobic in order to stay alive – they have to stay away from all people, because their own bodies will be invaded by an infection that actually does come from foreign parts and foreign people. They even have to wear masks and gloves, lest “foreign” infections invade their own pure bodies. Oh, the irony is rich indeed.

And all those one-world types, who hated borders – now have to stay inside the strictest of borders, their own homes.

As for the diversity and equality crowd – well, they have to keep at least six feet from everybody, because mixing with strangers can be deadly.

All these tired old narratives will now have to go the way of the dodo – because the Coronavirus Narrative has changed the world very quickly and very drastically; and no one is even noticing. In effect, there is now no “normal” to go back to.

The World Ahead

It is very startling and frightening that we have all so easily agreed to abandon all our freedoms. We want security at all cost.

Here is what has already been lost:

- All communities have broken down, since no crowd, no matter how small, can assemble. There can only be individualized allegiances to virtual groups, where only the pretence of a gathering can be provided online.

- The screen alone will mediate our transactions with the world outside our bodies.

- All supply chains are now fragile, if not broken. If enough workers decide not to show up to work, for fear of being infected, there is no supply.

- The service sector of the business model is in shambles. Places like barber-shops, restaurants, gyms, etc. are no longer “truth-worthy.” Suddenly, the very notion of the value of work is now gone

- Anyone who does not work and earn in front of a screen at home is now unemployed.

- Governments have quickly consolidated power. Suddenly, there are “Quarantine Laws” which are population containment directives. And a fearful citizenry has happily agreed to forego freedom and be put under siege by their own politicians.

- The notion that we all laughed at – safe spaces – is now law. We now all have been put inside safe spaces, from which we cannot emerge without permission from the state and the technocrats.

- Work is made useless, by being declared “inessential,” so that ordinary people no longer know how to pay rent, buy food and look after their families. We will have the rise of the “precariat,” people who will only barely find precarious work. And can it be that this mass unemployment will turn larger corporations to robotic work, making the situation far worse for ordinary people?

The world we knew has been lost – because we have lost the most important component of the world – trust.

More Hysteria

The Coronavirus Narrative is also an expression of our hyper-feminized culture, where manliness has lost all meaning and value. It is certainly pertinent that the word, “hysteria” comes from the Greek term for “womb, vagina.” What we have now is not a manly response to hardship, where we all say that we will persevere, we will continue to work, we will continue with life, even though life is always tough and at times deadly (for death is part of life).

Instead, we now encounter the world only in terms of nurturing. The only way possible to deal with hardship is to seek safety, as offered by the warmth of the womb, because the world is much too fearful a place.

Where is the moral courage? Where is the determination? Where is the call for us to be strong, no matter what the adversity? Where are the calls that say exposure to the virus will build immunity, though it may kill some? People who live in bubbles do so because they will die in the open air. Are we really demanding zero deaths each and every year?

No, no, let us just hunker down in our safe spaces, shut the world down; best to accept mass house-arrest, until the maternal-state figures out how to save us from the Grim Reaper, ravaging the world beyond our windows, our screens. We are safe inside. Nesting is the only answer to adversity we have left as a culture.

Where shall we go from here? There were other viruses before (like SARS, H1N1, avian) – and there will continue to be flu viruses from China each and every year, which will continue to kill thousands. (Perhaps the WHO, in its wisdom, might want to invest in a program to encourage the Chinese to change their eating habits and not kill so many of us each year?).

Will we have annual lockdowns every flu season? Will the Coronavirus Narrative, or some version thereof, become the only narrative that truly matters each and every year? Will we now redesign the very purpose of daily life to meet the expectations of this all-encompassing, mega-narrative of perpetual protection offered to us by the state?

Covid19 is not the return of the Black Death. But it is the return of the Great Fear, through which we are allowing petty tyrants (politicians) to usher us into the Dystopia of lost freedoms, oppressive governing structures, and rejigged economies that will always favor the privileged classes. A brave new post-Covid19 world, indeed.

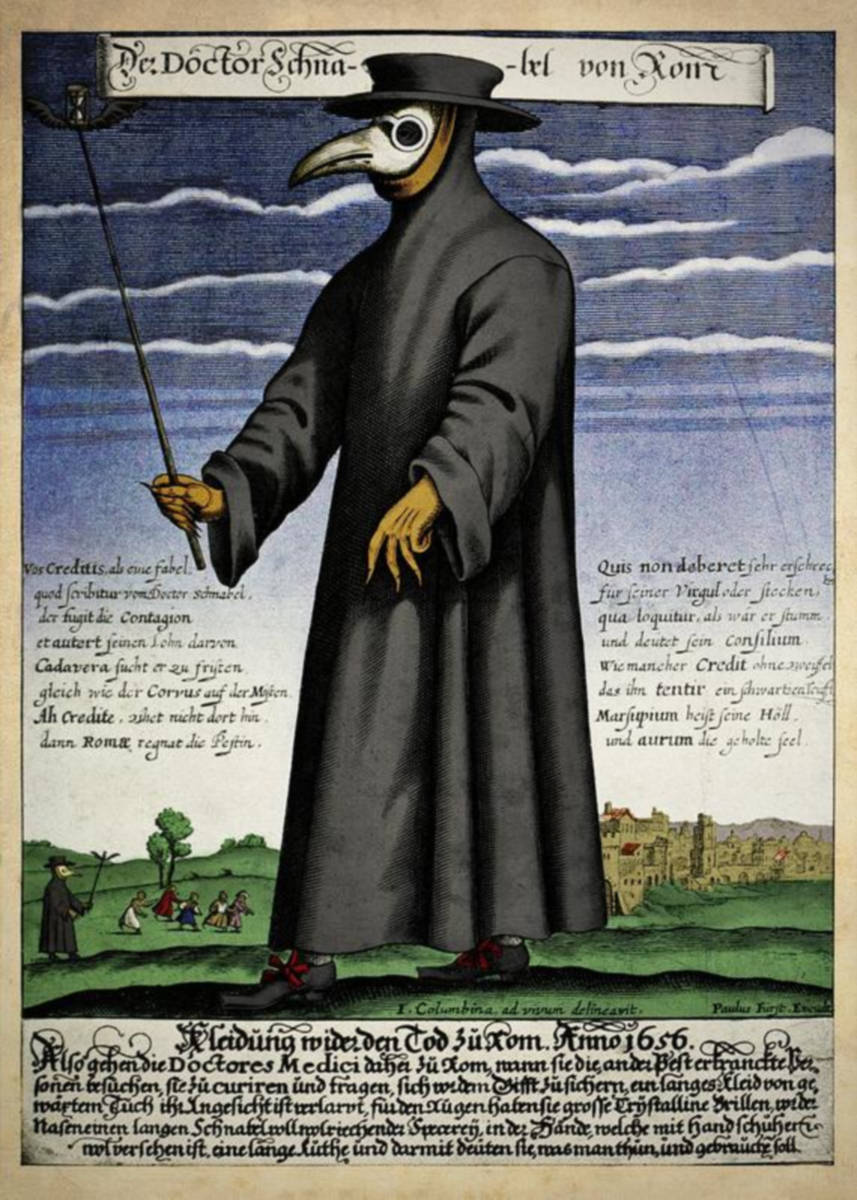

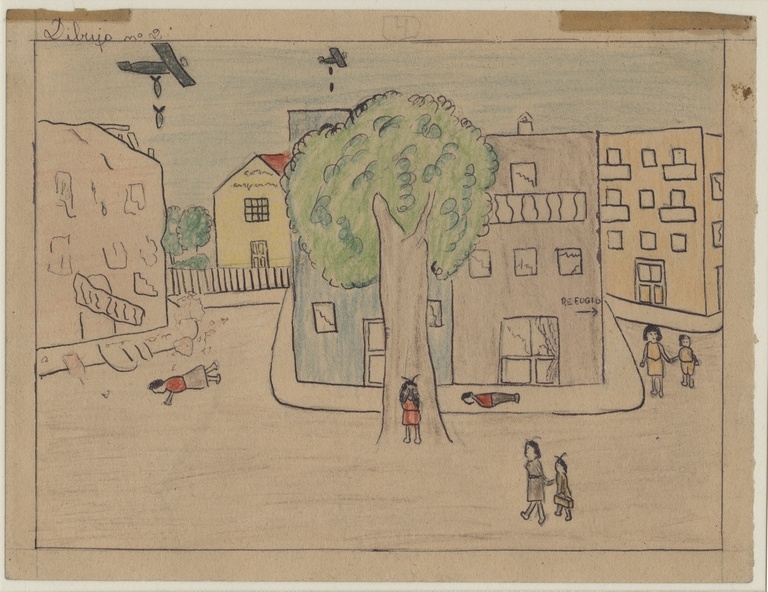

The image shows a plague doctor by Paul Fürst, 1656.