The properties (at the level of the composition of matter or that of its arrangement) which, at the instant t-1, find themselves to be actualizable are not only subject to decryption and to triage on the part of matter at the instant t. They rank among the possible implications of the properly atemporal (since virtual) bundle of the elementary archetypes of the cosmos, and its starting rules. Therefore, we may call them the “implicit properties” of matter (or the “implied”).

By the Spirit, I mean a purely virtual being (therefore devoid of the slightest material support), which is the substantial reality (the one self-sufficient to exist), and which is infinite as well as the creator and subject to a creative impulse, deploying itself like a selective impulse, which actualizes the own content of the Spirit. The latter has this paradoxical feature – that it is both outside of time (by reason of its supra-worldly character), and engaged in a process of revelation of itself over the course of the history of the cosmos (whose existence it generated from nothing).

The paradox is elucidated through taking into account the fact that the Spirit, which entirely lies at the axioms (the starting rules repeating in a fractal mode), and in the elementary archetypes of the cosmos, therefore lies in the infinite assemblage of their implications.

At each level of emergence in the composition or the arrangement of matter (starting with the emergence which saw matter spring from nothingness), matter – subjected to time and engaged in a momentum which we will see is, so to speak, the shadow or the reflection of the selective and actualizing impulse on the part of the Spirit – decrypts, sorts, and concretizes those implications. It does so on the occasion of the communication process that physicist Pavel V. Kurakin describes between matter at the instant t and the actualizable properties of matter at the instant t-1.

The Material Impulse Towards Selective Actualization

More precisely, the Spirit (all the components of which are traits of the Spirit that are essential rather than accidental) is entirely contained in an ideational (therefore atemporal and supra-worldly) assemblage of axioms, archetypes, and implications, whose actualizing drive transmits itself to matter. The latter, not content with embodying the ideational field which yet remains distinct from matter and ideational, therefore, takes care of the actualization of the aforesaid implications.

Yet the material accomplishment of the Spirit gradually leads to the consciousness of the Spirit (in the sense that the cosmos sees the knowledge of the existence of the Spirit germinate), as well as to the transparency of the Spirit (in the sense that the content of the Spirit allows itself to be known also). In other words, matter selects over the course of time passing in cosmic history – and as a result of an actualizing impulse that the Spirit breathes into the two partners that are time and matter – those implications arising from archetypes and axioms which will be actualized, and including the implication that consists of the emergence of consciousness among living beings – and, in essence, the emergence of the awareness of the Spirit’s existence, and of the knowledge of the Spirit’s content, within the thought of men (especially Faustian Westerners).

This process of a selective and material self-revelation of the Spirit has a temporal and worldly beginning. The advent of this beginning is the object of a global and undivided impulse (which nevertheless communicates itself to axioms, archetypes, and implications, namely, the components of the Spirit), rather than the object of a coalition of convergent but particular impulses (on the part of the aforesaid components of the Spirit).

Throughout the process of the Spirit revealing itself, matter—as Aristotle rightly discerned, carries within it the potentiality of the change that it experiences. Nevertheless, the aforesaid change 1) is operated by matter itself (in collaboration with time); 2) it inherits the actualizing and selective impulse on the part of a unified assemblage of (elementary or implied) archetypes and of axioms (and their implications); and 3) it concerns as much the constitution of matter as its organization. Those are the great many aspects of the change at work in the cosmos that were beyond the scope of Alexander’s mentor.

The Deployment Of The Spirit In The Cosmos

Ultimately the history of the cosmos can be apprehended as the history of the Spirit which, via its drive to create time and the world, as well as via its (breathed) drive to sort and to update the implications, accomplishes selectively its essence (therefore its content), unfolding over the course of time, which occasions the decryption (and the triage) of the implicit properties of matter (whether at the level of its arrangement, or at the level of its composition).

The materialized archetypal forms, as well as the materially and fractally iterated Big-Bang rules, which recruit matter into information processes taken over by the aforesaid matter, and reveal the Spirit in an exclusively objective mode (which therefore ignores the consciousness of the Spirit). Just as consciousness is unknown to the atom that partakes of the archetype of the self-recruitment of a matter composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons in rapid motion, within the spherical form of a shell within another shell – it is foreign to the galaxy which partakes of the archetype of the granting of an elliptical shape to the ten billion stars or more composing matter which gives itself such arrangement.

Nevertheless, consciousness emerges with the memes – ideologies, religions, worldviews in the broad sense – which continue to reveal the Spirit in an objective mode and which open the door to its subjective revelation. In order for the Spirit – which accomplishes itself on a material and historical level, while remaining supra-material and outside of time – to become the object of a consciousness and to be rendered transparent alongside the aforesaid consciousness, its objective fulfillment which goes through memes must become the place of its subjective accomplishment (instead of distancing itself from it).

The prolongation of the objective accomplishment into an accomplishment which is properly subjective, consists for the Spirit in revealing its existence – and in selectively revealing its essence – through the memes which proceed from the objective fulfillment. This subjective development accomplishes itself in the history of the Hellenic then Western civilizations, which is the history of the Spirit making its existence known – and rendering selectively its identity transparent – within Faustian man.

The Hegelian Fallacy

The seizure of the Spirit at stake is to be taken in the sense of the grasping of the notion of its existence – and in the sense of the knowing of what the Spirit reveals of its identity. It finds its first stage (as well as its engine) in the Promethean soul, the spirit of conquest, and the flavor of the infinite that are constitutive of the Faustian mentality, and which turn Faustian man into the heir and the continuator of the creative gesture of the cosmos. The latter – fulfilling new emergent realities via the fractal iteration (and the selective extraction of the implications) of a handful of starting rules of the cosmos (those being attraction and repulsion, integration and differentiation, fusion and fission), and within the framework of the aforesaid extraction – tending somehow towards increasing levels of order and complexity as concerns the organization of its matter and its constitution.

However, we cannot identify the (global) thought of Western Faustian men with the Spirit that it gradually learns to know. The aforesaid thought, far from being confused with the Spirit (which, in that way, would become aware of its own existence and of its own identity), is the work of the receptacle of the subjective development of the Spirit. Contrary to Hegel’s claims, European thought is not to be confused with the ideational field.

Hegel rightly said the ideational field accomplishes itself in cosmic and human history. But he failed to grasp the exact nature of its articulation within the cosmos. Indeed, he wrongly conceived of the ideational field as immanent in the cosmos and as identified with the final state of European thought towards which human thought is supposed to proceed inevitably.

It is just as wrong that the (either subjective or objective) unfolding of the Spirit responds to a pre-established final point, a prefixed finish line, of human and cosmic history. Man (especially Faustian man) is to be conceived of as made in the image of the Spirit – rather than as the Spirit in person. And the selective fulfillment of the Spirit into matter – and through matter extracting and sorting the implications which arise from elementary archetypes and from axioms – must be seen as a continual and error-prone improvisation. It must be approached as a movement that is no more perfect than it is predetermined, but which persistently strives to generate an increasing complexity in the universe.

A Reassessment Of Platonism From The View-Point Of Incarnation

By recognizing his own creative impulse, his own boarding of matter, in the generative gesture of axioms and archetypal forms, the Faustian man will become aware of himself as made in the image of the cosmos that fulfills the Spirit. This relationship of the European man – so long as he is shaped by a bioculture secreting the Faustian mentality – to the Spirit revealing itself in the cosmos is anticipated in Judaism. For the latter represents to itself man as made in the image of God – and as mandated to crown creation under the aegis of linear (rather than cyclical) time.

As concerns the Christian Trinity, it incidentally gives us a symbolic illustration of the relationship of the Spirit to its creation.

1) The Father symbolizes the Spirit insofar as it is located on a virtual and atemporal level – that of implications, axioms, and elementary archetypes.

2) The Son symbolizes the Spirit insofar as it gives itself an existence material and subjected to the reign of time. Matter drawing, sorting, and fulfilling – within the framework of the aforesaid incarnation – the implications arising from archetypes (and from axioms that matter repeats in a fractal mode) over the course of time, which occasions the communication between matter at the instant t+1 and the actualizable properties of matter at the instant t. And the Spirit – far from its ideational existence rendering itself properly immanent to the cosmos – nevertheless remaining atemporal and supraworldly (which brings us back to the mystery of the Incarnation).

3) The Holy Spirit symbolizes the Spirit, insofar as its drive selectively actualizing its own content, is breathed into matter. Matter selecting those implications (to arise from axioms and from archetypes) which will be actualized; and striving – at each passing moment and, a fortiori, at each incremental level of emergence – to hoist matter to an unprecedented and higher level of complexity (as concerns its composition or its arrangement).

Contrary to the Gnostic vision, my analysis does not envision matter as the prison of spiritual realities (in the sense of what is virtual as opposed to material). The Spirit – the field of axioms (and their implications) and of (elementary and implied) archetypes – does not find itself to be trapped in matter. It finds in matter the way, the place and the means of its (objective and subjective) accomplishment – while remaining rigorously exterior to matter in its properly ideational existence.

As such, we should no longer consider cosmic and human history as the story of the progressive triumph of the Spirit over matter – the story of its gradual emancipation from matter. Rather, what we find is the history of the improvised and imperfect effort of matter (which embodies the Spirit) in the direction of an increased order and complexity – and at the level of the composition of matter and of its arrangement.

As for the primordial unity that Plotinus investigated, he was wrong to conceive it as a unity that stands beyond the multiple – instead of approaching it as a unity unifying a certain multiplicity. For the One merges with the impulse crossing the Spirit and unifying the field of (elementary) archetypes, axioms, and implications (the latter jointly arising from the aforesaid axioms and from the aforesaid archetypes).

To the Spirit (the unified ideational field) and to the Momentum (the actualizing and selective impulse on the part of the Spirit) is added a third and last principle: A third and last pillar of the architecture of reality. It consists of Philo of Alexandria’s Word mentioned in the prologue to the Gospel of Saint John. The Word is here envisioned as the movement through which the actualizing momentum of the Spirit renders itself material and temporal, while remaining virtual and atemporal – and while operating in parallel with matter, and in ways that we are about to explore. From this incarnation, proceeds the communication to which matter is devoted – the communication between matter at the instant t and the implicit properties of matter at the instant t-1 – and the generation, on the part of matter, of changes at the level of matter’s arrangement or its composition.

Beyond The Schopenhauerian “Will To Live”

The impulse on the part of the Spirit to realize itself into matter is an impulse jointly undivided and unifying of the ideational field. It accomplishes itself by duplicating itself into matter. While, in the ideational field, the only impulse at work is that, undivided, which engages the Spirit in its entirety; the same is not true in the material field, in which the Momentum mysteriously declines itself into a set of distinct impulses. They are those of natural beings – the ones among concrete beings, which take charge of their own information.

While the impulse on the part of those of natural beings which are not gifted with thought must be envisaged as an impulse (of self-information) that excludes deliberation (and which is not accompanied by the idea of its existence), the impulse on the part of thinking beings consists of a momentum conscious (of itself). In the case of those of thinking beings which are in possession – up to a certain point – of free will, this conscious momentum will enjoy (limited) self-determination on the part of the deliberation preceding and determining the aforesaid momentum. But we should notice that those of natural beings which are not gifted with thought may be nonetheless gifted with an ability to determine freely a part of their own behavior – as pointed out by the late physicist Freeman Dyson, in the case of atoms.

Placed end to end, the particular impulses (on the part of natural beings), which are distributed in time and space, give a cosmic impulse to incline towards perpetually increasing levels of order and of complexity. This impulse is the fruit of an addition of distinct impulses; but it translates the indivisible impulse on the part of the Spirit.

Schopenhauer rightly sought to discern the presence underlying material entities (and their laws) of an undivided impulse, which he called “will,” or the “will to live.” He nonetheless he remained wrong when he approached the aforesaid impulse as inherent in material entities – instead of associating it with the ideational field. The latter breathing its undivided impulse into concrete beings, while retaining it within it – and while dividing it into a multitude of particular impulses in the material field. Schopenhauer was just as wrong when he approached the undivided “will” as spurred towards the sole preservation of the universe identical to itself – rather than towards the enrichment of the cosmos in an ever increasing complexity.

More precisely the actualizing (and undivided) impulse on the part of the ideational field is articulated with the material field in two ways.

1) On the one hand, the aforesaid impulse, which is outside of time, generates the properly temporal beginning of matter. On the occasion of this generation, the Spirit conserves its own actualizing impulse (in the properly ideational field), while transmitting it to matter – and while transmuting the aforesaid impulse into a variety of distinct impulses on the part of those material beings which are natural.

2) On the other hand, matter deciphers, sorts, and updates – over the course of communication that time occasions – the implications that the virtual field carries within it. The (selective) extraction of those implications is the object, in parallel, of the undivided impulse on the part of the ideational field and of the cosmic impulse which results from the sum of the distinct impulses in the cosmos – the given object of the cosmic impulse at a given moment in the universe, coinciding with the object of the impulse of the Spirit at the same moment; and past, present, future succeeding one another in the cosmos, subjected to time, while they are simultaneous in the ideational field, which exists outside of time and space.

The atemporality of the momentum of the Spirit is therefore not to be taken in the sense that it would ignore the past, the present, and the future – the aforesaid impulse only ignoring their successive (rather than simultaneous) character. As for the insufflation of the ideational impulse to matter, it is not accompanied more by the cessation of the exercise of the aforesaid momentum of the Spirit. As the cosmic impulse operates, sp the impulse of the Spirit jointly operates. But their respective objects coincide at each instant, and the former is only the double of the latter.

The Bees Of Hidden Time

By virtue of the jointly atemporal and improvised character of the impulse of the Spirit, the future of the aforesaid impulse (which coincides with the future of the universe) has the remarkable feature of being not (totally) predetermined, but nonetheless remaining simultaneous with the present and with the past.

The paradox at the heart of the precognition of clairvoyants is their ability to know in advance a future which, however, is (in part) free and random. It can be resolved in these terms. Namely that at the present instant, their intuition of the impulse of the Spirit equates to an intuition of the future of the aforesaid impulse; the latter being simultaneous with its present and with its past – which does not exclude the fallibility of supra-sensible intuition.

I must emphasize the debt of my conception of time, as occasioning communication between matter (including the particles which are constitutive of atoms) at the instant t, and the implicit properties of matter at the instant t-1, and my conception of the starting rules of the cosmos as pairs of opposites which the cosmos fractally repeats at each level of emergence, to the philosopher, Howard Bloom. Bloom develops them both in his book, The God Problem. His communicational approach to time is also discussed in his work, “Dialogue model of quantum dynamics,” co-written with Pavel V. Kurakin and George G. Malinetskii, and taken up in Constructive Physics, by Yuri I. Ozhigov, as well as in the article by Kurakin entitled, “Hidden variables and hidden time in quantum theory.”

Bloom proposes an analogy between the spring behavior of the hive and that of a subatomic particle which, in the exact interval separating two stages of time, chooses among the possible detectors the one towards which it will move. During the interval of 10-35 seconds (namely one Planck unit) which separates the instant t from the instant t+1, and that Kurakin calls “hidden time,” a subatomic particle, hesitating between possible detectors, sends waves which are (metaphorically) so many exploratory bees. Once back from their wanderings, they consult with each other to take a collective decision as to which detector they will select. This decision is not taken during a certain period of time, but actually in the intermediate space (between the instant t and the instant t+1), where the succession of instants is suspended. Here, the behavior of an elementary particle (at the instant t+1 which is about to be) can, at its leisure, interpret and sort the implicit properties of the aforesaid particle (at the instant t which has ended).

Any investigation of the cosmos which reveals the Spirit must bear in mind that our knowledge of the Spirit does not deal with the whole of its essence, the latter being infinite (since it harbors the infinite field of the possible implications which arise from elementary archetypes and from axioms). Our knowledge of the cosmos deals with the finite unfolding for which the Spirit opts in the material field – the particular unfolding that the Spirit chooses (among the infinite list of the finite unfoldings that are possible for it). The recapitulation of the history of the cosmos (as we suspect it) lets us glimpse that the effective unfolding of the Spirit – the accomplishment for which the Spirit effectively opts – is an unfolding which consists in extracting (and in sorting) the implications in a way that spurs (not without hazards) the cosmos towards the generation of an ever-increasing order and complexity.

The knowledge of the (selective) fulfillment of the Spirit, which amounts to the knowledge of the course of the cosmos and the laws which govern it, mobilizes conjecture (and induction) from the sensible given, just as it passes through clairvoyance. By clairvoyance, I mean the supra-sensible grasping of ideational entities, be it elementary archetypes, those implied (and actually selected), axioms, or the (selected) implications of the aforesaid axioms. In both cases, the investigation, which is liable to error, requires theorizing and conceptualization – thus, the use of definitions which, it is good to specify, are properly informative statements.

In the weak sense, the definition of a given notion collects (and exposes) a certain number of qualities of the concrete entity to which the aforesaid notion corresponds. Defining the notion thus amounts to describing the aforesaid entity. In the strong sense, the definition of a given notion identifies (and formulates) those of the qualities of a given entity which are necessary and constitutive qualities of the aforesaid entity.

Here is the paradox. Any strong definition – at least, any strong definition which is correct from the point of view of language – can be reduced (via the play of synonyms) to a proposition true for any distribution of truth values, therefore a tautological proposition within the framework of first order logic. Nonetheless, the tenor of (material or ideational) reality serves as the court for the validity of strong definitions from the point of view of the aforesaid reality. Therefore, the accepted strong definition of a given concept will be both tautological in the eyes of language and informative – endowed with content, descriptive – in the purview of (the confrontation of language with) reality.

The synonymic relationship of a given notion to the strong definition attached to it (within a given language), while it does not have to be justified in the purview of the concerned language, cannot escape the judgment of reality. If the aforesaid synonymy amounts to a synonymy, it is genuinely because language believes that the tenor of reality allows it to see synonyms in the terms concerned – for example, single and not engaged. Since the criterion of the validity of synonymies (and of strong definitions) with respect to reality resides in reality itself, our knowledge of which is however perfectible, it may turn out that a given strong definition is jointly true from the point of view of our language, and false from the point of view of reality. Because those of the qualities of the defined entity which are retained as constitutive and necessary are really contingent (at least in part) – and seem to us to be constitutive and necessary only by reason of our imperfect knowledge of the defined entity.

Let us suppose that in a given language, the strong definition of the species of swans is that of swans as large palmiped birds whose plumage is white, and whose neck is long and flexible. The discovery of a bird who shares all those qualities except that its plumage is black (rather than white) will force the strong definition of the swan – the strong definition of the singular swans considered from the aspect of their species – to cease to include the white plumage among the common qualities of the swan. And therefore to cease to include the aforesaid white plumage among the necessary qualities of swans – and among the elements of the strong definition of swans.

In this example, the involved mode of knowledge of a given singular entity is the one by means of induction – that which strives to identify the essential and contingent qualities of a given entity (here a given swan), on the basis of the observation of the regular and irregular features of a certain number of observed swans. It opposes the mode of knowledge consisting in directly grasping the ideational archetype of the species of swans. This supra-sensible seizure is potentially imperfect – and likely to make the same mistake of identifying the white plumage as a common and necessary quality of swans.

A Brief Recapitulation

To sum up, the two distinct levels of reality I investigated are inversely symmetrical.

1) The arrangements of archetypes play an active role of informing the virtuality which they are made of. While the arrangements of material entities – at least in the case of those of material beings which are natural – are the fruit of information taken over by the innate matter of concrete entities.

2) The impulse of the ideational field is jointly undivided and atemporal. The cosmic impulse (whose object coincides, at all times, with that of the impulse of the Spirit) is not only the sum of distinct impulses (on the part of natural beings) within the cosmos; it is an aggregate, whose objects follow one another (over the course of time) – while the past, the present, and the future of the Spirit’s impetus remain simultaneous for their part.

Thus, I elucidated the fulfillment of the Spirit into matter – and through matter taking charge of its own information (and occasionally generating additional levels of matter via the aforesaid information) – as a dual process. Indeed the actualization of the implications is both on the part of the Spirit actualizing them outside of time, and on the part of matter progressively actualizing them. This joint process continuously improvises; it is a concerted march whose final point is not pre-established.

Then, I elucidated the horizon towards which are tending matter, and the Spirit which incarnates itself into matter, as the generation of perpetually increased levels of order and complexity at the level of the cosmos – more precisely, at the level of the composition and the arrangement of the matter which the cosmos is composed of.

Finally, I elucidated the means used for this purpose as the selection on the part of matter (and on the part of the Spirit) – and over the course of time, occasioning a communication between matter at the instant t and the implicit properties of matter at the instant t-1, and of those of the implications contained in the ideational field which contribute to the realization of an increasing order. This selection is not immune to error.

Reconciling Plato And Heraclitus

All in all, notable mistakes by Plato in his appreciation of the ideational field (and the way the latter is articulated with the material field) were the ones following ones, in that Plato considered the ideational field as a flattened (rather than hierarchized) assortment of general archetypes:

1) Within the ideational field, the archetypes are really coexisting with the fractal starting rules of the cosmos.

2) Besides this, we find, among the aforesaid archetypes, a class of elementary archetypes and a class of implied archetypes – which means the Ideas are hierarchized.

3) And we find a class of general archetypes (such as the general archetype of the dachshund) and a class of particular archetypes (such as the singular archetype of a singular dachshund).

Further, Plato conceived of the material and mobile field only as a passive exemplification of the ideational field – and he considered the latter as immobile.

1) Matter veritably incarnates the Spirit, which however remains exterior to it.

2) And, in the context of the aforesaid incarnation, matter plays the active role of deciphering, sorting, and actualizing the implications that arise from elementary archetypes, as well as those which follow from the starting rules of the universe that matter iterates in a fractal mode at each incremental level of emergence.

3) This extracting process is a result of the impulse, on the part of the ideational field, to sort and to actualize its own content; the ideational field retains its impulse while paradoxically communicating it to matter.

4) The process takes place over the course of time occasioning the communication between the actualizable properties of matter at the instant t-1 and matter at the instant t.

Far from the movement being unknown in the ideational field, the Spirit is therefore impelled towards the selective actualization of the implications which it carries within it. The stages of this improvised actualization are nevertheless simultaneous – and cosmic evolution is ultimately the shadow of it, cast on the walls of the cavern of the material field. I should add that my conception of the primordial unity as the impulse unifying the ideational field – and continuously generating the cosmos from elementary and implied archetypes, and from axioms and their implications – solves the problem of the One posed in the Parmenides.

I approached time as working – in partnership with matter, laden with harmonious and fractal contradictions – to endow with material fulfillment the ideational field incarnating itself into matter. An achievement whose pursuit is confused with the execution (somehow) of a perpetually increasing order in the cosmos. Yet my approach revives three insights by Heraclitus.

As already pointed out by Heraclitus:

1) Time, far from being only the stage on which change is played out, constitutes “a child playing with pawns,” therefore a full-fledged player in engendering the aforesaid change.

2) The opposites mate and collaborate to the advent of change. I restituted those pairs of opposites as being those of differentiation and integration, fission and fusion, and attraction and repulsion.

3) The permanence of change in the universe is nevertheless accompanied by the presence of a “logos” which orders (and renders intelligible) the universe.

A logos, which I believe I can identify as the process through which the ideational field renders itself material and temporal (while remaining ideational and rigorously exterior to the world in which it incarnates itself) – and which sorts and actualizes the implications present within it (while seeing its actualizing and selecting momentum decline itself at the level of matter subjected to time); and thus directs cosmic evolution in the direction of an order and complexity perseveringly and imperfectly increased.

Grégoire Canlorbe is an independent scholar, based in Paris. Besides conducting a series of academic interviews with social scientists, physicists, and cultural figures, he has authored a number of metapolitical and philosophical articles. He also worked on a (currently finalized) conversation book with the philosopher, Howard Bloom. See his website: gregoirecanlorbe.com.

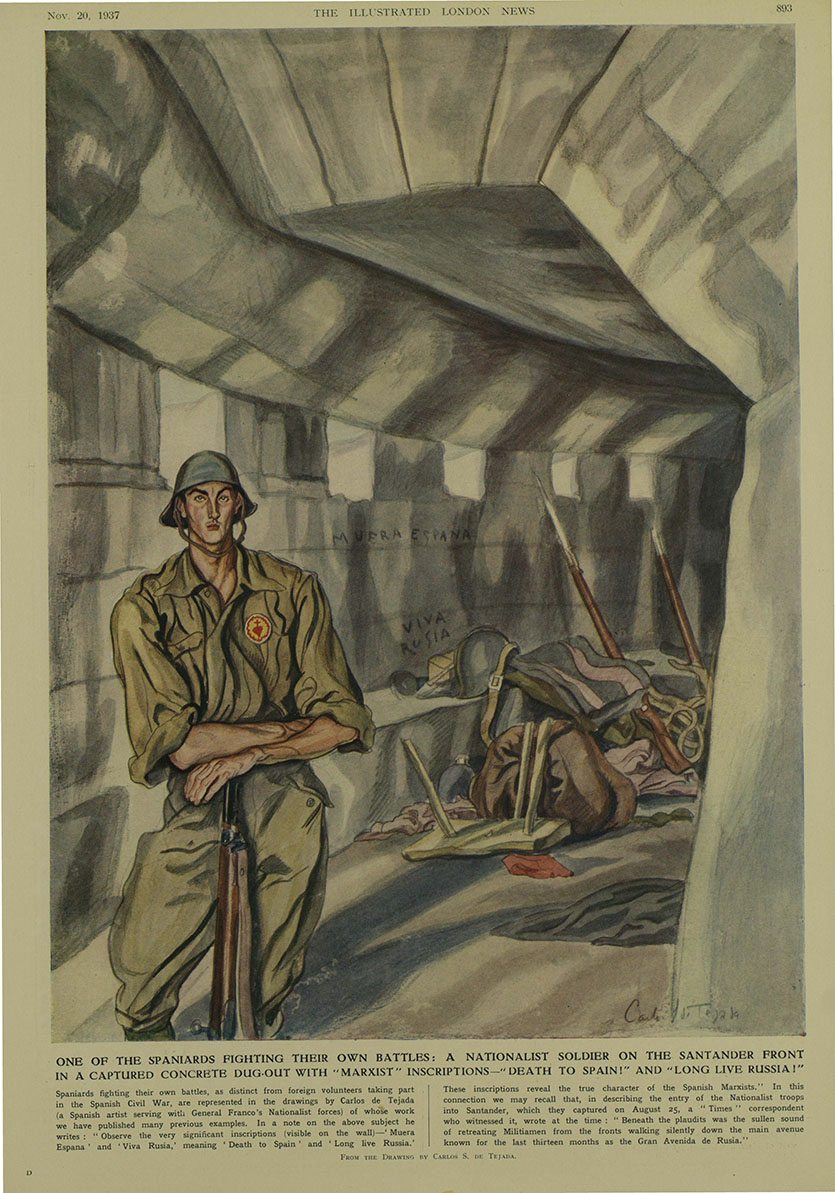

The image shows, “The Oak and the Reed,” by Achille Etna Michallon , painted in 1816.