Labels can be misleading, they can, as Scruton pointed out, control speech, but they can also show our orientation or direction of thought.

The immediate inspiration for writing this short essay was the recent passing of Roger Scruton, the conservative’s conservative. I need not repeat all of the wonderful pieces that have been written about him. There are, however, two things I want to emphasize. Scruton and I were roughly contemporaries and we had our epiphany, unknown to each other, at the same time.

In 1968, Scruton was in Paris and witnessed the uprising. He has remarked that he suddenly realized the difference between himself and the rioters. The rioters, many of them intellectuals or inspired by French intellectuals, were interested primarily in tearing things down – believing, in romantic Marxist fashion, that the good will rise automatically from the conflagration of the old. Scruton suddenly realized that he was not interested in destroying things but in preserving what was most valuable.

From that moment one he became one of Britain’s most outspoken and courageous conservatives. At the same time, riots were occurring across America’s campuses, including my own university. Until that moment I had naively thought of myself as a liberal reformer, on the correct side of all of the major social issues. To see the destruction of higher education in America, although the corpse is still around, to see administrators unable and unwilling to defend the crucial importance of my beloved institution made me realize that I was also a conservator of our cultural institutions.

More recently I watched a U-tube presentation of Scruton trying to explain to a Dutch audience what was behind Brexit. He mentioned a number of things, including how his parents’ generation had successfully defended the UK from Nazi invasion, how Britons had no need to launder their recent history, how Britain was a bottom-up society and the home of the rule of law. It is the last point that inspired my recent publication of a book to substantiate that claim and to remind myself and others of the unique Anglo-American heritage.

Recognizing the confusion caused by labels, especially labels with a long history and multiple meanings, I nevertheless choose to call myself a ‘conservative’. This choice reflects the fact that the intellectual world is dominated by people who call themselves ‘progressive’, that progressivism seems to control the terms of discussion, and my instinctive desire to speak truth to power. Prudence has never been one of my virtues.

Before explaining my positive understanding of ‘conservatism’ I want to note what I disagree with in progressivism. To begin with, I object to bullying, to the silencing of dissent, the suppression of what used to be called free speech, and to coercing and penalizing people who oppose progressivism. Second, I am opposed to radical ‘social’ change instituted by the government and justified by appeal to abstractions designed to achieve a utopian goal. Third, I object to the invariable and inevitable distortion of the previous sentence by those who will attribute to me the position of opposing all social change.

What I mean by ‘conservatism’ is two things. First, it is impossible to think and speak about anything without employing an inherited background of norms and assumptions. We cannot explain or critique anything from a wholly external perspective. Our intellectual and social inheritance contain many norms, and there is no systematic way of organizing those norms without appeal to some extraneous perspective or without promoting one norm to a prominence it cannot rightfully claim. A good deal of what passes for philosophy is the elevation of one intellectual practice above all others. Our inheritance is too rich and complex to be so systematized. Progressivism is an example of the illicit claim of being ‘the’ uber framework. Rigidity is thus always on the side of Progressivism.

Our plurality of norms evolved over time (sorry, Moses) and reflected a particular set of circumstances. Inevitably and of necessity new sets of circumstances will lead us to recognize additional norms and conflicts and tensions within the norms we already have.

How then do we resolve these conflicts? The better or more accurate question, is what has our practice of conflict resolution or management been? Borrowing from Oakeshott, I would say our practice has been to engage in a conversation that begins by diagnosing our situation; we make proposals about what the response should be; we recommend this proposal by considering a large number of the consequences likely to follow from acting upon it; we balance the merits of any proposal against those of at least one other proposal; and we assume agreement about the general conditions of things to be preferred. Arguments constructed out of these materials cannot be ‘refuted’. They may be resisted by arguments of the same sort which, on balance, are found to be more convincing. The recommendation always involves a rhetorical appeal, an appeal to what we believe are the relevant overriding norms – the general conditions of things to be preferred.

The human condition can never in this life be utopian. Some good things can only be purchased by abstaining from other. We cannot choose everything. To open some doors is to know that others must remain closed.

What I seek to conserve is our practice. Progressives threaten our practices in the name of some abstraction. Armed with some such abstraction (e.g. ‘equality’) they will disrupt the conversation by claiming that the equal right to free speech means that any speaker they do not like can be shouted down. In vain do I remind them of what J.S. Mill said about censorship. In vain do I remind them that successful reformers like Martin Luther King prevailed because they reminded others into acknowledging what the inherited norms were.

For progressives, words (e.g. ‘racism’, ‘sexism’, etc.) mean only what they choose the words to mean. Any appeal to “the general conditions of things to be preferred” is illegitimate because what we thought were the relevant overriding norms (note the plural, please) is rejected as an appeal to something illegitimate. What are the legitimate norms? It is what they say it is and as they alone understand their holy abstraction.

On the contrary, I want to conserve the conversation, and the civility implied therein. It may very well be that there can no longer be a conversation. Communities do sometimes disintegrate, split into multiple communities, or find it necessary to destroy one another. Those who hold onto the illusion that the community can and must always be preserved (‘do-gooders’) are giving in to the belief in ‘the’ uber framework. Progressives, like Bolsheviks, always win in these situations because they will never concede anything. The ‘do-gooders’ will concede anything and embrace an Orwellian discourse. Progressives may control the commanding heights, but like all barbarians, in the end, they can only appeal to force.

As a “conservative” I want to preserve the inherited community, warts and all, not embrace an abstraction; I do embrace the need for periodic review; I vehemently oppose those who pretend to be conservatives but are merely intransigent about something or other; I patiently endure the process by which we engage in reform, however slow and painful. I am ready and willing to oust the disingenuous progressives (as opposed to the merely confused) who pretend to be inside the community in order to enjoy its benefits but reserve for themselves the exclusive privilege of not being bound by it when it suits their private agenda. I am prepared to let them go their way; but they cannot stay as is. The progressives will claim that I am the one who is leaving when in fact they are the ones who have abandoned the community long ago. To be a ‘conservative’ is to choose to stay and to be willing to pay the price; it is not to idolize any one institution.

Nicholas Capaldi, a Legendre-Soule Distinguished professor at Loyola University, New Orleans, USA, is the author of two books on David Hume, The Enlightenment Project in Analytic Conversation, biography of John Stuart Mill, Liberty and Equality in Political Economy: From Locke versus Rosseau to the Present, and, most recently, The Anglo-American Conception of the Rule of Law.

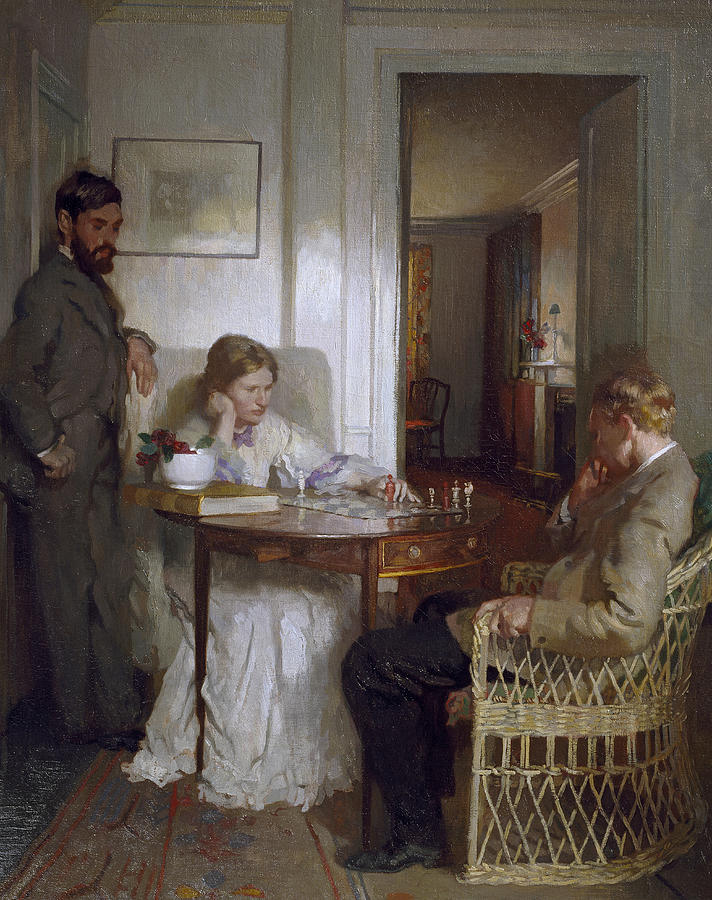

The image shows, “The Chess Players,” by Sir William Orpen,” panted before 1902.