It has been said that Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky achieved distinction in three separate careers, all in the field of aviation. He created the world’s first multi-engine airplane in Russia in 1913; he launched a second career in the United States and became famous for his Flying Clippers; lastly, he conceived and developed the world’s first practical helicopter. He is best known, perhaps, for this third career.

He was born in Kyiv, Imperial Russia (now Ukraine), on May 25, 1889. As a boy, influenced by his mother, a medical school graduate, and his father, a doctor and a psychology professor, he showed an interest in science, particularly aviation. He built and flew model aircraft; he became acquainted at an early age with Leonardo da Vinci’s theory of the flying screw. He was 14 when Wilbur and Orville Wright made their historic flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, and that event, more than any other, decided his career. He spent three years at the Naval College in

St. Petersburg, and was still a student at the Mechanical Engineering College of the Polytechnic Institute in Kyiv when he determined to build his first helicopter.

He traveled to Paris, then the aeronautical center of Europe, where he met some of the early names in aviation, men like Louis Bleriot, first to fly the English Channel, before returning home with a 25 horsepower Anzani engine. He built his first helicopter in 1909, his second in 1910. The second accomplished what the first did not — it proved able to lift itself -but it was unable to sustain the weight of a pilot.

HistoryMr. Sikorsky turned to fixed-wing planes and, in 1910 made his first solo in an aircraft of his own design and construction. His approach was practical; he made-sketches of the plane he wanted to build, built it, then trained himself to handle it, correcting his errors as a pilot as he corrected errors in design.

He defied the experts of that early period by building the first four-engine airplane in 1913. The plane, called The Grand, included such luxuries as an enclosed cabin, a washroom, upholstered chairs, and an exterior balcony for passengers. The Grand was followed by a larger aircraft, called the Ilia Mourometz, after a legendary Russian hero of the 10th Century, which, in a military version, proved highly successful as a bomber in World War I. More than 70 of these bombers were built.

The Revolution ended Mr. Sikorsky’s career in Russian aviation. He traveled to the United States in 1919, after short stays in England and France. Lectures to Russian immigrant groups gave him money for room and food, while he dreamed of new conquests of the air. America had been a beacon to him. “As a youth, I was impressed by the skyscrapers that were taller than anywhere else,” he recalled in 1967, “by the railroad system that included more miles of rails than the total of the rest of the world. I was inspired by the achievements of such men as Edison, Ford, and others, and in my case particularly, the Wright Brothers.”

In 1923, he organized the Sikorsky Aero Engineering Corporation on a farm near Roosevelt Field on Long Island. The first aircraft built was the S-29-A, the A for America, a successful twin-engine, all-metal transport. A number of other aircraft followed, including the S-38 amphibian which Pan American Airways used to blaze new air trails to Central and South America. Mr. Sikorsky’s company became a division of United Aircraft Corporation in 1929, and the combination gave aviation a series of historic flying boats. The first 40-passenger Flying Clippers were built in 1931, followed by the first transoceanic flying boat, the S-42, which pioneered commercial air transportation across the Pacific and Atlantic.

By 1938, the pioneering of oceans was over, and Sikorsky returned seriously to the field of vertical lift. Through the years, he had kept notes on ideas for helicopter designs. His first helicopter, the VS-300, was begun in early 1939 at the Vought-Sikorsky plant in Stratford, Connecticut by fall, it was completed, a strange-looking tubular skeleton which rose a few feet from the ground on September 14, 1939.

The VS-300, in point of time, actually dates back to 1929 when Mr. Sikorsky concluded that a successful helicopter soon would be possible. In 1931 he applied for a helicopter patent that incorporated most of the features of the VS-300. There was one main lifting screw and a small auxiliary rotor at the rear of the fuselage to counteract torque. The VS-300 was powered by a four-cylinder, 75-horsepower, air-cooled engine; it had a three-bladed main rotor, 28 feet in diameter, and a welded steel frame, a power transmission combination of v-belts and bevel gears, a two-wheeled landing gear, and a completely open pilot’s seat. The VS-300, now part of the Ford Museum at Dearborn, Michigan, established a world endurance record by staying aloft an hour and 32 minutes on May 6, 1941. Thus, the helicopter fundamentals were established.

There was a period of evolution in the VS-300. Mr. Sikorsky tried 19 different configurations before he was satisfied with the final design. Military contracts followed, and in 1943 large-scale manufacture of the R-4 made it the world’s first production helicopter. Public acceptance of this strange new vehicle, however, was far from immediate. The helicopter had to prove itself. It did just that in the Korean War, serving as a troop transport and rescue aircraft; men injured in combat were flown directly to field hospitals, their chances of recovery greatly enhanced.

Mr. Sikorsky saw the helicopter as a vehicle that freed aviation from dependence on airports. The helicopter’s ability to take off and land vertically was a breakthrough long dreamed by engineers, but never fully realized until Mr. Sikorsky launched his third career. The helicopter gradually established its versatility in peace and war, but Mr. Sikorsky himself found the greatest satisfaction in the knowledge that helicopters were responsible for saving tens of thousands of lives as rescue aircraft. Pilots of rescue helicopters have contributed “one of the most glorious pages in the history of human flight,” he said in 1967. “It is to these gallant airmen that I address my thankfulness, respect, and admiration,”he said

A deeply religious man, Mr. Sikorsky wrote two books called “The Message of the Lord’s Prayer” and “The Invisible Encounter.” In summation of his beliefs, in the latter he wrote: “Our concerns sink into insignificance when compared with the eternal value of human personality — a potential child of God which is destined to triumph over lie, pain, and death. No one can take this sublime meaning of life away from us, and this is the one thing that matters.” He also wrote an autobiographical account of his life in aviation called “The Story of the Winged S.”

His contributions to aviation brought him many honors and awards. In 1952, Thomas K. Finletter, then Secretary of the Air Force, presented Mr. Sikorsky with the National Defense Transportation Award and said: “He is a milestone in the history of aviation, an equal giant and pioneer. Look upon him well and remember him.” In 1966, Mr. Sikorsky was named Man of the Year by the Air Force Association. Congratulating him on the award, President Lyndon B. Johnson said: “Your skill and perseverance have broadened the horizons of man’s progress.”

In 1967, accepting the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy of the National Aeronautical Association, Mr. Sikorsky expressed his belief in the importance of the individual, a belief that carried him stubbornly past frustrations and failures to success in his three careers. “Creative work is still with us,” he said, “still here to stay, and still remains a tremendously vital factor in the progress of mankind. The work of the individual still remains the spark which moves mankind ahead.”

Igor I. Sikorsky, the legendary aviation pioneer, will long be remembered as the man who gave the world its first practical helicopter.

This achievement alone was significant enough to ensure the gentle Russian immigrant’s place in the history books, but it was only one facet of an extraordinary man’s remarkable career … a career that paralleled the history of powered flight.

Often described as a humble genius, Mr. Sikorsky had already achieved worldwide recognition in two other fields of aviation before he built and successfully flew his VS-300 helicopter in 1939.

Born in Kiev, Imperial Russia,(now Ukrain) on May 25, 1889, Mr. Sikorsky developed an early interest in aviation, thanks largely to the influence of his mother, who was a doctor, and his father, a psychology professor.

A youthful tour of Germany in the company of his father, during which he first heard of the Wright brothers and came in detailed contact with the work of Count Zeppelin, more or less settled the question of what career the youthful Sikorsky was to follow.

He graduated from the Petrograd Naval College, studied engineering in Paris, returned to Kiev and entered the Mechanical Engineering College of the Polytechnical Institute in 1907. But in 1909, his young mind full of aviation, Mr. Sikorsky went back to Paris, then the aeronautical center of Europe, to learn what he could of the embryo science.

While in Paris, he became known to many of the men who later were to make great names in aviation – Bleriot, Ferber, and others. Despite advice to the contrary from these and other experienced men, Mr. Sikorsky announced plans to build a helicopter. Having learned all he could of aviation as it was then known in Europe, he bought a 25 h.p. Anzani engine and went home to Kiev to begin building a rotary-wing aircraft.

The helicopter failed, as did its successor due to a lack of power and understanding of the rotary-wing art. Undiscouraged, Mr. Sikorsky then turned his attention to fixed-wing aircraft.

First success came with the S-2, the second fixedwing plane of his design and construction. His fifth airplane, the

S-5, won him national recognition as well as F.A.I. license Number 64. His S-6-A received the highest award at the 1912 Moscow Aviation Exhibition. and in the fall of that year the aircraft won for its young designer, builder and pilot first prize in the military competition at Petrograd.History

Mr. Sikorsky’s success in 1912 led to a position as head of the aviation subsidiary of the Russian Baltic Railroad Car Works. In this position, as a result of a mosquito-clogged carburetor and subsequent engine failure, he conceived the idea of an aircraft having more than one engine -a most radical idea for the times. With the blessings of his parent company, he embarked on an engineering project which gave the world its first multi-engine airplane, the four-engined “The Grand.” The revolutionary aircraft featured such things as an enclosed cabin. a lavatory, upholstered chairs and an exterior catwalk atop the fuselage where passengers could take a turn about in the air.

His success with “The Grand” led him to design an even bigger aircraft, called the Ilia Mourometz, after a legendary 10th Century Russian hero. More than 70 military versions of the Ilia Mourometz were built for use as bombers during World War 1.

The Revolution put an end to Mr. Sikorsky’s career in Russian aviation. Sacrificing a considerable personal fortune, he emigrated to France where he Historywas commissioned to build a bomber for Allied service. The aircraft was still on the drawing board when the Armistice was signed and Mr. Sikorsky, after casting about in vain for a position in French aviation, traveled to the United States in 1919.

After another fruitless search for some position in aviation, Mr. Sikorsky resorted to teaching. He lectured in New York, mostly to fellow emigres. Finally, in 1923, a group of students and friends who knew of his reputation in prewar Russia pooled their meager resources and launched him on his first American aviation venture, The Sikorsky Aero Engineering Corp.

The first aircraft built by the young and financially insecure concern was the S-29-A (for America), a twin-engine, all-metal transport which proved a forerunner of the modern airliner. A number of aircraft followed but the company achieved its most significant success with the twin-engine S-38 amphibian, which Pan American Airways used to open new air routes to Central and South America. Later, as a subsidiary of United Aircraft Corporation (now United Technologies) Sikorsky’s company produced the famous Flying Clippers that pioneered commercial air transportation across both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The last Sikorsky flying boat, the S-44, held the Blue Ribbon for the fastest trans-Atlantic passage for years. All Sikorsky aircraft of the time were known for ease of handling and luxurious comfort.

With two careers behind him and the oceans conquered, Mr. Sikorsky turned once again to the helicopter. Through the years he had jotted down ideas for possible designs, some of which were patented.

Finally, on September 14, 1939, Mr. Sikorsky took his VS-300 a few feet off the ground to give the western hemisphere its first practical helicopter. His dogged determination and faith in his own ability to build what many considered to be an impossible vehicle established the bedrock upon which today’s helicopter industry rests.

Military contracts followed the success of the VS-300, and in 1943, large-scale manufacture of the R-4 made it the world’s first production helicopter.

The R-4 was followed by a succession of bigger and better machines and since then, the helicopter has clearly established its ability to perform a myriad of difficult missions, including the saving of thousands of lives, in both peace and war. Mr. Sikorsky was especially proud of the helicopter’s life saving ability and of organizations such as the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service which had put helicopters to what he believed was their finest use. During his career, he rarely passed up an opportunity to stress this role or praise the men whose skill and courage made the rescues possible. The pilots of rescue helicopters have contributed “one of the most glorious pages in the history of human flight,” he once remarked.

The awards and honors accorded to Mr. Sikorsky fill nine typewritten pages and include the National Medal of Science, the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy, the U.S. Air Force Academy’s Thomas D. White National Defense Award, and the Royal Aeronautical Society of England’s Silver Medal. He is enshrined at both the International Aerospace and the Aviation Halls of Fame.

Although recognized primarily as a practical inventor of material things, Mr. Sikorsky was also a deeply religious visionary and philosopher with an intense interest in man, the world and the universe. Remembered by those who knew him as a kind and considerate person with a sincere concern for his fellow man, Mr. Sikorsky’s two sides are perhaps best described in the following quote from his friend Anne Morrow Lindbergh:

“The thing that’s remarkable about Igor is the great precision in his thought and speech, combined with an extraordinary soaring beyond facts. He can soar out with the mystics and come right back to the practical, to daily life and people. He never excludes people. Sometimes the religious minded exclude people or force their beliefs on others. Igor never does.”

Although he never attempted to force anyone to accept his beliefs, Mr. Sikorsky wrote two books, “The Message of the Lord’s Prayer,” and “The Invisible Encounter,” as well as numerous pamphlets, to express them.

In the first book, Mr. Sikorsky expressed his belief in a final destiny for man and a higher order of existence, while in the second, he pleaded that modern civilization has a greater need for spiritual rather than material power.

It was Mr. Sikorsky’s abiding faith in God and his strong belief in the importance of the individual that helped him overcome the frustrations and failures that marked his career.

Mr. Sikorsky liked to say that “the work of the individual still remains the spark which moves mankind ahead,” and he proved it throughout his life.

Even after his retirement in 1957 at the age of 68 Mr. Sikorsky continued to work as an engineering consultant for Sikorsky and he was at his desk the day before he died, on October 26, 1972, at the age of 83.

Dan Libertino is the President of the Sikorsky Archives, whose kind courtesy has made this article possible.

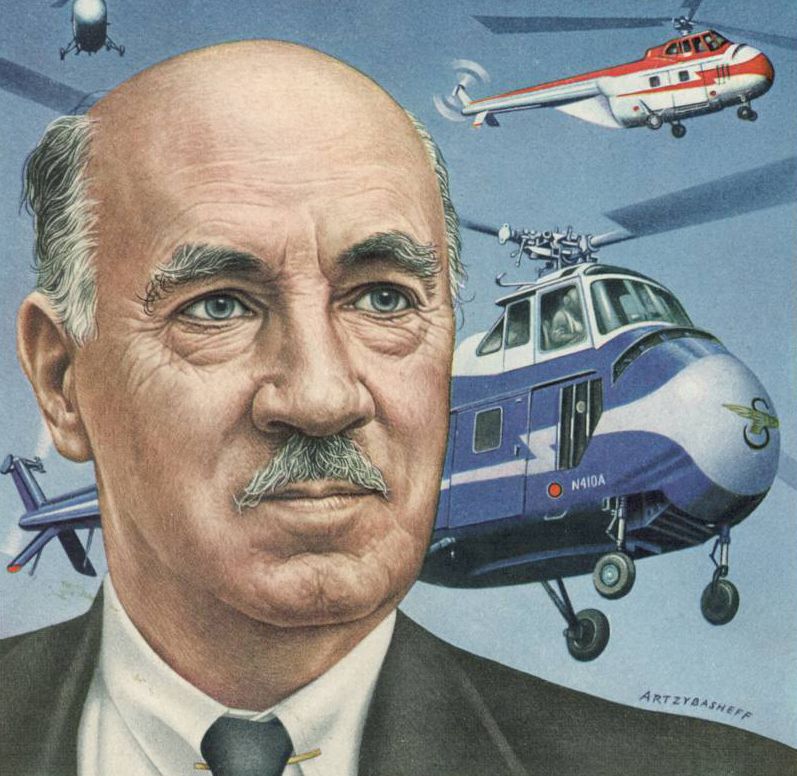

The featured image shows a protrait of Igor Sikorsky, by Boris Artzybashef.