Charles-Henri d’Andigné is a journalist for Famille chrétienne and also contributes to Figaro Magazine. Here he talks about his latest book, Cent livres pour comprendre le monde: petite bibliothèque pour un catholique d’aujourd’hui (A Hundred Books to understand the World: A little Library for Today’s Catholic)—a remarkable synthesis of one hundred important works to know.

He is in conversation with Christophe Geffroy, the publisher of La Nef magazine, to whom we are grateful for this opportunity to publish the English version of this interview.

Christophe Geffroy (CG): In this book you present an impressive array of authors. What was your goal and how did you choose?

Charles-Henri d’Andigné (C-HA): My goal is to offer Catholics, and men of good will in general, a set of books that provide reference points in an era when everything is fluid and changing, and when we are losing sight of the most obvious facts.

Modern man believes he can do whatever he wants, say whatever he wants, think whatever he wants! We Catholics are more affected than we think by this generalized hubris.

The one hundred books I have written about are so many beacons in this uncertain and changing world: philosophical, theological, historical and sociological beacons.

I wrote my book like a bouquet: there are lilies and roses, and then there are violets—I borrow this metaphor from Saint Therese of Lisieux. In other words, there are the great authors, Maritain, Bernanos, Camus, Brague, and then more modest authors, Alix de Saint-André or Gerald Durrell, to form a whole that I hope is harmonious. And accessible—I am addressing the general public.

CG: Why is it important for a Catholic to have a certain culture when Christ rejoices that his Father did not reveal the things of Heaven to the “wise” and the “clever” but to the “little ones” (cf. Mt 11:25)?

C-HA: The Gospel tells us that Christ did not come for an elite group of people who know, but for everyone, young and old, without leaving anyone by the wayside.

Christianity is not a gnosis for the initiated. However, we must cultivate ourselves, as the farmer cultivates the land, so that it may bear beautiful fruit. As François-Xavier Bellamy reminds us in Les Déshérités (The Disinherited), to which I dedicate a chapter, culture humanizes us, helps us to be more ourselves. This is all the more vital in an era rich in mortifying ideologies. Without true culture, there is no intellectual immunity—ideologies penetrate you easily like a hot knife cutting through butter.

CG: Man, God, history, society are the four main parts of your book. In what way do these themes intersect with the essential problems facing our us?

C-HA: Simply because the great ideologies to which I referred are all more or less materialistic. They turn us away from God; they turn us away from man, who thereby becomes only be an individual driven by his economic or sexual interests; they turn us away from the historical and social facts that then used to impose their propaganda.

I don’t need to tell you to what extent this propaganda is present in schools, in the media and now in big companies which impose re-education courses to their employees.

CG: Although all the authors selected are not Catholics or “conservatives” in the broadest sense, this dual belonging is nevertheless dominant. Do you also take on this marked commitment? And what do you say to those who would reproach you for it?

C-HA: I take on this commitment perfectly. We suffer a lot from “deconstruction,” based on the belief that nothing exists in a natural way, that everything is a social construct and that therefore everything is “deconstructable;” better that everything must be deconstructed, so that we can finally be free. The result is an isolated individual, an offspring of his own works, who does not inherit, does not transmit anything and has no other links with his peers than those related to his interests.

It is therefore urgent to reconnect with our religious, philosophical and historical traditions, in order to preserve what deserves to be preserved. Gustave Thibon, one of “my” hundred authors, defines himself as a conservative anarchist. Of course, conservative does not mean narrow-minded. One can have a conservative sensibility and read authors considered as left-wing, Orwell or Simone Weil to name but a few. Hence my chapters on Nineteen Eighty-Four and The Need for Roots.

CG: For Christians, how do you see the struggle of ideas in society (its importance, its influence)? And do Christians seem to you to be up to this struggle? In other words, is there today a credible Christian intellectual succession?

C-HA: Some Christians seem to have understood the importance of the struggle of ideas after the adoption of “marriage” for all. Having never heard of gender theory, they could not even conceive of the notion of same-sex marriage. Are they now up to the task of fighting this battle of ideas? I fear that this is not yet the case.

But the Christian intellectual succession is there. Let us mention just one name, that of the philosopher Olivier Rey—I dedicate a chapter to Une question de taille (A Question of Size)—one of the finest and most profound minds of his generation.

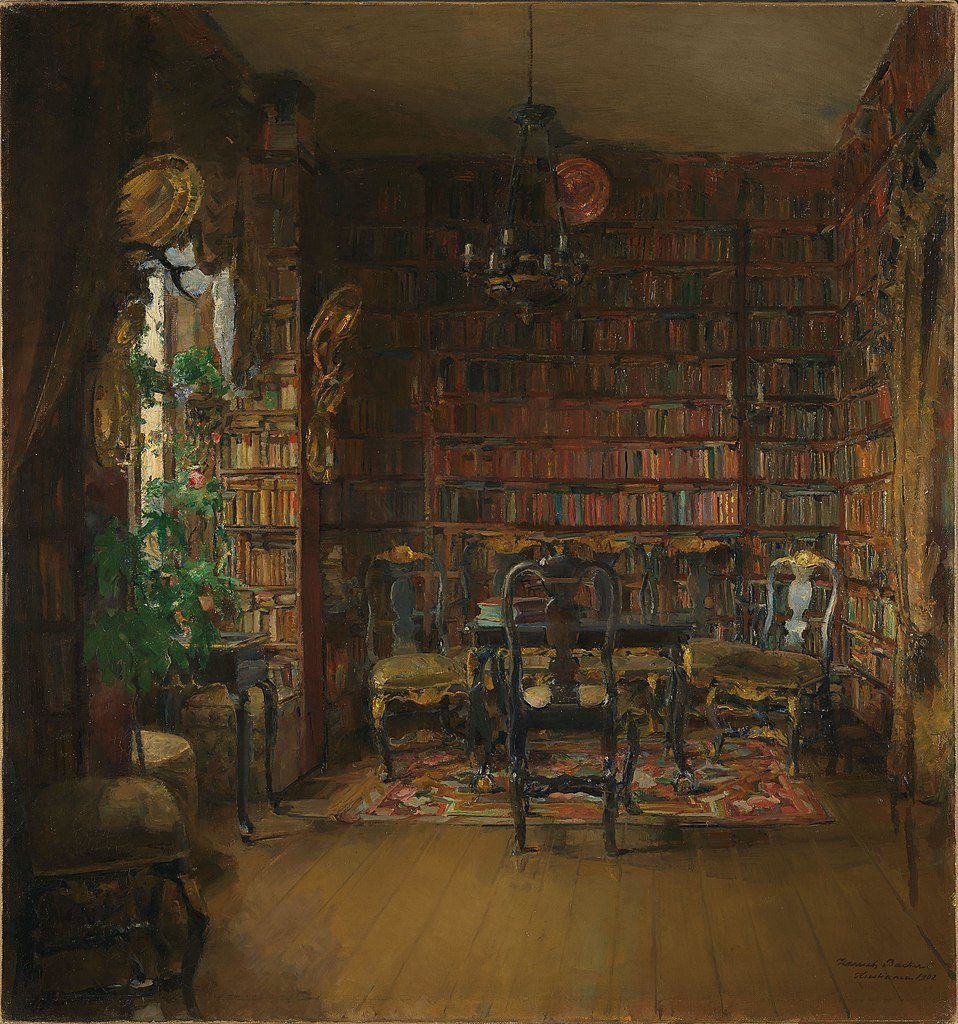

Featured image: “The Library of Thorvald Boeck,” by Harriet Backer; painted in 1902.