It is only in Heaven that we will see the truth about everything. On earth, it is impossible. So, even for Sacred Scripture, isn’t it sad to see all the differences in translation. If I had been a priest, I would have learned Hebrew and Greek, I would not have been satisfied with Latin, as I would have known the real text dictated by the Holy Spirit.

(Saint Therese of Lisieux, “The Last Interviews,” in the Yellow Book of Mother Agnès, August 4, 1897).

Thérèse of Lisieux is undoubtedly right, but to learn the language in which our Lord deigned to express himself, we must ask ourselves what that language was. Jesus could not ignore the Hebrew language, that of Revelation, but it was then no more than a liturgical language, what today we would call a “dead language.” The oral language, the language of communication, was Aramaic, the history of which begins with that of the men who brought it with them.

These Aramaeans were Semites who burst out of the desert to conquer the fertile lands of Mesopotamia and Syria. They went everywhere, settling, seizing supplies, creating little kingdoms.

Then arose Assyria, the empire of war, of force, of power – the “Hitlerites of the ancient world.” As soon as Assyria awakened, the various small Aramaic kingdoms disappeared, one after the other. But they left their language and their gods to the world.

This language, the Assyrians themselves would adopt. On several figurative documents concerning Aramaic origin, in particular on one of the frescoes of Til Barsip, we see depicted side-by-side an Assyrian scribe who writes on a tablet, and an Aramaic scribe who writes on a sheet of parchment or papyrus (13th century to the 9th century BC). But what the Assyrians instituted was not a properly Mesopotamian dialect of Aramaic but common Aramaic. Thus, a body of Aramaic scribes was officially constituted inside Assyrian administration.

In 632 BC, the Assyrians disappeared from the face of the earth. Then a new power arose – the Persians.

They were called the Achaemenids, among whom the prominent name is Darius the Great. With the Achaemenids, the Iranians became “the imperial race of Asia,” to use Roman Ghirshman’s phrase. In terms of political organization, Greece hardly arose beyond the polis – the State remained the City there. The Persians, for their part, developed an entity which, in its unity, encompassed countries of various races and cultures, united by the cogs of a vast administration. and above all else, these peoples were protected by a powerful army against foreign domination (especially against the persistent threat of nomads from the North and East). This empire, which remained a warrior one, was nevertheless driven by a desire for association rather than the thirst for domination, so characteristic of Assyria that always retained a powerful fascination.

The Achaemenids also made the linguistic choice of Aramaic, for reasons, no doubt, a little different than those which motivated the Assyrians; and it indeed seems to be a more conscious choice.

The use of cuneiform for writing Old Persian dates back at least to Teipses (as evidenced by the gold tablet of his son, Ariaramnes). At the time of the transformation of the small kingdom of Pars into empire, this language and this writing were only accessible to a minority of the ruling class. However, the rapidity of the formation of the Achaemenid Empire precluded the possibility of translating Persian into all languages. It was therefore necessary to choose an already existing language. But, also, by this time, Aramaic had spread throughout anterior Asia to western Iran. It was therefore Aramaic that the Persians adopted.

The Achaemenids had three other languages of culture, but it was this fourth language that they chose. Persia owes a great deal to the Kingdom of Urartu. From Urartu came the use of the breastplate. The Urartians transmitted their arts and techniques to the Iranians, as well as their strategy of conquest in their great symbols. According to Herodotus (III, 85), Darius obtained his crown thanks to his squire and his horse, just like King Rusa of Urartu. The traditions of the Urartian chancelleries were followed by the Persians: it is only in the Urartu texts that a royal inscription is divided into parts, so each one begins with “Thus spoke King X…,” which is found in the inscriptions of Achaemenid kings.

The most famous piece of Achaemenid glyptic belongs to Darius the Great. It is inscribed with his name and bears a text written in three languages. The use of cuneiform writing was not, however, completely abandoned, though it was reduced to stone inscriptions on monuments.

Thus, being already a lingua franca throughout the Near and Middle East, with the Achaemenids, Aramaic took on the status of an official language throughout Asia; and it remained in use, in particular in state affairs, from Egypt to India, where documents written in Aramaic have been found. If in Elam, one wrote in Elamite, and in Babylon in Babylonian, then all the Persian chancelleries used Aramaic.

The Achaemenid Persians also then were the enemy to be defeated, for Alexander the Great. The archives of the Achaemenid Empire were kept in Ecbatana (the Bible makes it clear), and the excavations at Persepolis and Suza confirm this. Alexander stored there all the treasures of the capitals looted during his campaigns.

This Hellenization, which is held to be the marvelous consequence of this lightning raid of unheard-of insolence, actually began long before, and rather peacefully. It was when the ancient kingdom of Urartu was formed (ca. 800 BC) that a slow expansion of the Greeks around the coasts of Asia Minor took place. Greek merchants had found on the Pontic coast iron, wax, linen, wool, precious metals, cinnabar, bronze, wood, furniture, fabrics, as well as Elamite and Median embroidery. Iran was not excluded from trade between Greece and the East. On the contrary, there was an Irano-Urartian koine, which then extended from the Oxus to the Ganges, and indisputably linked artistic traditions (some attest to the links between Crete and Iran), and therefore to techniques, in particular, metallurgy. And all interaction was probably not in one language.

Alexander’s conquest marked a pause in the development of Persian art (constant for seven centuries), as in all likelihood the use of Aramaic also marked a pause. But Alexander’s empire did not last. Thereafter, the Parthians came to the forefront of history, firmly determined to oust the Seleucid monarchy, one of the three monarchies that were heir to Alexander, and thus to reconquer Iran. They took a little over a century to accomplish all this. At the time of the Achaemenid Empire, the region where these Parthians settled existed under the name of the “Parthian satrapy.”

The Parthian Empire was born in a great expansion of the Iranian tribes of the steppes which spread to the four corners of the horizon, from the Black Sea with the Sarmatians, to the mouth of the Indus with the Saka, and from the Euphrates with the Parthians to eastern India with the Kushans. This vast area, despite the diversity of peoples and countries, climates and landscapes that it contained, became what René Grousset called, “outer Iran,” where a composite yet enduring civilization was established. Such was the Parthian element that founded, rebuilt, enriched, and stabilized civilization in this part of the world.

Much of Parthian history took place during the reigns of thirty-two kings, all of whom bore the same name, Arsaces; hence the Arsacid dynasty If they chose the path of Iranism, it was not only because they believed it more capable of supporting them in their fight against the Seleucids, then vis-a-vis the Romans who claimed to realize in their Eastern policy the imperialist conceptions of ‘Alexander the Great, but because the Parthians were more Iranian than Greek. It was not just a political choice, but a deep affinity. It was a conscious decision, not solely a political choice.

And for this reconquest and this refoundation, the Parthians relied on the language that the Achaemenids, of whom they considered themselves to be successors, had adopted before them, namely, Aramaic, which was also then made the language of the chancellery. The ostraca that have been found are either bilingual (Indo-Aramaic, or Greco-Aramaic), or only in Aramaic. This means that Aramaic extended as far as the Kushan empire and therefore Bactria, which had long been Hellenized (historians speak of the Greco-Bactrians).

Their empire lasted five centuries, and it was nurtured by an unprecedented event.

In 105, King Mithridates II received the first Chinese embassy in his capital of Hecatompylos. He concluded a commercial treaty with China, which guaranteed him monopoly on silk. The center of gravity of the Persian world now changed – from the banks of the Tigris, it moved towards Bactria and Sogdiana. Many cities were then transformed into merchant cities, provisioning and training the leaders of the caravans, including Palmyra, which was to be called to a singular destiny.

Thus, under the pax parthica, in the first century of our era, two men set out. One was called Bartholomew, the other Thomas. In the heart of Asia, where Iran was the cultural engine, but which had chosen the Semitic language of Aramaic, and within an empire which felt a particular sympathy for the Jewish world, these two men were to go far, even to the ends of the earth, to evangelize and to found churches.

The Word not only prepared His coming, He also prepared the conditions for the dissemination of His Message. And by learning the language in which our Lord deigned to speak, we can focus on understanding the role that that language has played in history in general and in that of Christians in particular.

Marion Duvauchel is a historian of religions and holds a PhD in philosophy. She has published widely, and has taught in various places, including France, Morocco, Qatar, and Cambodia.

[The original article in French was translated by N. Dass]

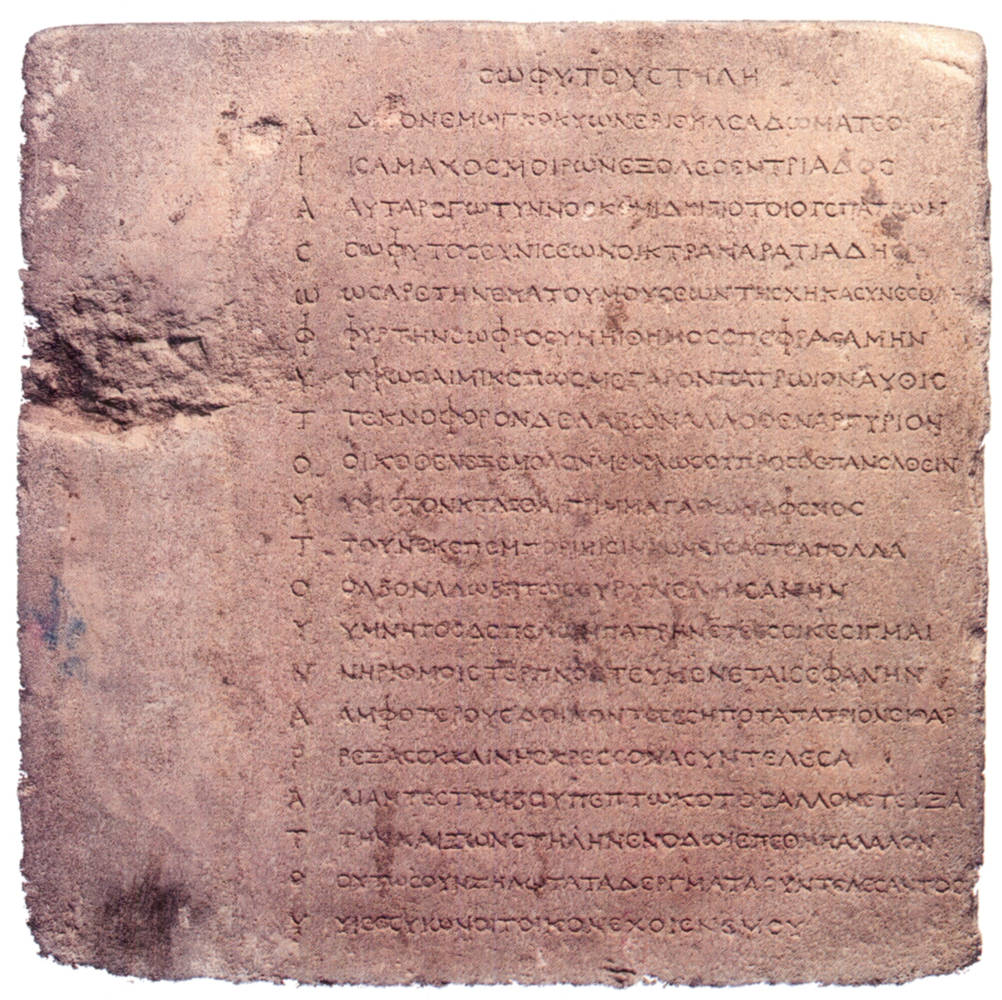

The featured images shows “the Kandahar Sophystos Inscription,” ca. 260 BC, or later. It is a metrical, bilingual (Greek and Aramaic) inscription. The Greek acrostic down the side reads: “ΔΙΑ ΣΩΦΥΤΟΥ ΤΟΥ ΝΑΡΑΤΟΥ (Dia Sophytou tou Naratou): By Sophistos, son of Naratos.”