This month we are greatly honored to present this interview with Professor Andrzej Waśko, the foremost authority on Romantic literature in Poland. He is the author several important books and currently serves as the advisor to Mr. Andrzej Duda, the President of Poland. Professor Waśko is here interviewed by Dr. Zbigniew Janowski, on behalf of the Postil.

Zbigniew Janowski (ZJ): Let me begin this conversation with a question about your recent article about the popular band Queen. You are a scholar of Polish Romanticism. You wrote your first major work, which received a national award, on Adam Mickiewicz (the prince of Polish Romantics) and your second on Polish conservative Romantic Zygmunt Krasinski. The role they played in Poland (along with the third major poet Juliusz Slowacki) may be compared to Byron, Shelley and Keats in England.

All of them belong to an epoch which existed two hundred years ago. The English rock group Queen was popular in the 1970s and 1980s. How come a professor of literature writes about about popular music?

Andrzej Wasko (AW): These topics are not as far apart as they seem. The aesthetic revolution, called Romanticism, which broke out in Europe after the French Revolution, began earlier with the rehabilitation of popular songs and with the ballads of Goethe and Schiller; and later with Wordsworth and Coleridge, Mickiewicz and others.

A similar phenomenon occurred in the 1960s, in the genre of popular song on the “lower” level of culture. Joan Baez and other folk music performers began their careers with the same or similar folk ballads. At that time, the post-war generation, largely made up of university-educated workers’ children, was knocking on the gates of the middle class. These people needed their mythology and it was provided, at least to some extent, by popular music – Joan Baez, as already mentioned, Nobel Prize winner Bob Dylan, and many others.

Here, I see a certain analogy to the situation that took place in the 19th century. Romanticism gave a cultural identity to the bourgeois and popular masses that began to build modern nations on the ruins of class-based society. The history of pop music is the story of what happened to society in the second half of the 20th century. Besides, today there is a radio in every car. Popular songs are a topic that a literary historian can talk to a taxi driver about.

ZJ: Your last remark reminded me of Allan Bloom’s conversation with a taxi driver. This is what he wrote in The Closing of the American Mind (1987): “A few years ago I chatted with a taxi-driver in Atlanta who told me he had just gotten out of prison, where he served time for peddling dope. Happily, he had undergone ‘therapy.’ I asked him what kind. He responded, ‘All kinds—depth-psychology, transactional analysis,’ but what he liked best was ‘Gestalt.’ Some of the German ideas did not even require English words to become the language of the people. What an extraordinary thing it is that high-brow talk from what was the peak of Western intellectual life, in Germany, has become as natural as chewing gum on American streets. It indeed had its effect on this taxi-driver. He said that he had found his identity and learned to like himself. A generation earlier he would have found God and learned to despise himself as a sinner. The problem lay with his sense of self, not with original sin or devils inside him. We have here the peculiarly American way of digesting Continental despair. It is nihilism with a happy ending.”

One may draw many conclusions from Bloom. One such is that once high-brow ideas fall to a level of ordinary people, the inevitable result is nihilism. Let me invoke the lyrics of Queen:

Empty spaces.

What are we living for?

Abandoned places.

I guess we know the score.

On and on.

Does anybody know what we are looking for?

Another hero,

Another mindless crime

Behind the curtain.

(“The Show Must Go On”).

Queen’s song and Lennon’s “Imagine” – “no heaven, no hell” – can be said to repeat the basic building blocks of Existentialism, especially the ideas we find in Simone de Beauvoir and Sartre. De Beauvoir and Sartre considered the world without God to be a reason to rejoice. Camus, on the other hand, was deeply troubled by it; he understood that in such a world the only jurisdiction of philosophy is suicide. This is not different from what we find in Queen: “does anybody know what we are looking for?” Are these songs existentialist philosophy of the Parisian cafes turned nihilistic?

AW: The fact that the songs you quote and probably many others show traces of the existential philosophy of Parisian gurus, such as Sartre and Camus, seems very likely to me. Certainly, Lennon welcomes the vision of an axiological void and proclaims it as “good news,” just like Sartre.

Both the philosopher and the ex-Beatle call for a revolution, each in their own way. In practice, however, Lennon’s way turns out to be more effective, because his song is pretty, it reaches the masses and moves their emotions. But the lesson Lennon gives his followers leads to nihilism – in a world where there is nothing to die for – “nothing to kill or die for” – there is nothing to live for.

This was understood by Camus and I think also Freddie Mercury, whose lyrics, on the contrary, are not cheerful. “What are we living for?” – in a world devoid of essence, without absolute values and absolute norms. Of course, this is also existentialism for the people. But at the same time it is a lamentation over a world ruled by nihilism.

Taxi drivers I speak with in Poland are more likely to lament and never say anything about psychology, which is otherwise a very fashionable field at universities in Poland. Rather, it is the establishment that thinks like the Atlanta taxi driver Bloom writes about. This is pure and self-conscious nihilism – but it is rather rife among teachers and students at universities.

ZJ: You made a connection between the aesthetic revolution of Romanticism and the post-French revolutionary world. In 1833, Benjamin Disraeli wrote in his Diary: “My mind is a continental mind… It is a revolutionary mind.” What Disraeli is referring to is the influence Romanticism had on him. What made Romanticism such a powerful social force?

Second, for all the greatness and beauty of Romantic poetry, Romanticism turned out to become a political outlook which shuttered the old order no less than the French Revolution. Is there a connection between the slogans of the Revolution – equality in particular – and the Romantic exaltation of self-consciousness as the source of truth and a fountainhead of artistic creativity?

AW: What made Romanticism a social force was certainly the democratization of the language of literature and art, an example of which is the turn to ballads. In his Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth tells us that poetry should speak the language that people actually use in their lives. The explanation lies in the saturation of art with emotions. Wordsworth and Coleridge talk about this in the Preface as well. This is the hallmark of Romantic literature – unlike the classics, the speaking subject in romantic poetry is always in a state of some emotional agitation, a mood he then communicates to his audience.

This is simple, and pop culture of the 20th century has similar features – it expresses the emotions and infects its audience. And contemporary people living in an extremely rationalized world, living in Le Corbusier’s “machines for living,” do not become machines – on the contrary, they want to react to the coldness of social institutions in which they find themselves. They want to cry or feel euphoric. They want to feel “like gods,” or lose themselves in a “great whole” – a service provided by, along with drugs, ecstatic music. In this regard, pop music of the second half of the 20th century uses some elements of Romanticism in an intensified and simplified form.

Your second question concerns individual self-realization and creation, which are inventions of literary Romanticism. Based on idealistic German philosophy, Romanticism builds the concept of the subject as creator – of poetry (from the Greek poiesis – creation), but also a creator of various geniuses. Napoleon changed the world thanks to his genius. Byron changed the world thanks to his genius, too. It’s a status of the self in society and in politics. It is a challenge for everyone, including me. Perhaps this is what Disraeli thought.

ZJ: Should we take the idea of genius to mean a way of democratization of politics as well? I do not mean democratization in the sense of universal suffrage and an electoral system; but in the sense of opening the public and political realm to people who in the past could never see themselves as social or political leaders. Being a genius became a form of political passport, if you will. It provided a new form of socio-political legitimacy. Poets became national bards, unelected national leaders.

AW: Yes, both the cults of genius artists (“prophets”) and the cults of charismatic political leaders have something to do with democratization in the sense you suggested. The genius embodies the characteristics of the community that recognizes him as its representative, as the medium of its thoughts and feelings, as the embodiment of the aspirations and goals it pursues. As Rzewuski put it: “There is a sympathetic bond between a genius and his people.”

ZJ: You mentioned Byron, an artist, who saw himself as having a social, political message. Let me quote here a stanza from Childe Harold:

Hereditary bondsmen! know ye not

Who would be free themselves must strike the blow?

By their right arms the conquest must be wrought?

Will Gaul or Muscovite redress ye? no!

True, they may lay your proud despoilers low,

But not for you will Freedom's altars flame.

Shades of the Helots! triumph o'er your foe!

Greece! change thy lords, thy state is still the same;

Thy glorious day is o'er, but not thine years of shame.

This is his message to the Greeks, calling on them to rekindle past greatness, to shake off the yoke of the Turkish oppression. This kind of message, formulated by poets, seems to be common for the Romantic period. We find it also in Juliusz Slowacki’s Agamemnon’s Tomb.

Could one say – call it a wild guess, if you want – that Romanticism created a path to a new political reality, wherein artistic geniuses (poets, writers, painters) but also all kinds of political charlatans, madmen and social reformers could call on a nation, or the world, to action? First it was done under the banner of liberation (as in Greece), or unification (as in Italy, or Germany), and later, in the 20th century, as a call to a regeneration of national spirit (as in Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy). Now, in the 21st century, we hear an echo of national slogans: “Great China,” “Making America Great Again,” “Poland – A Great Project” (the name of an annual conference), and so many others.

Politics, before the American and French Revolutions, was a domain of one class, the upper class. But 19th century Romanticism changed it.

AW: Yes, Romanticism paved the way for charlatans as well; it gave them a certain role model. But you cannot blame the Romantics for the actions of charlatans like Hitler or Mussolini, who adopted the dress of geniuses. Otherwise, you could then also accuse Rubens or Rembrandt of paving the way for picture forgers. Morally and politically, everyone is responsible for himself.

Also, we should not toss together all political slogans designed to mobilize supporters with references to the greatness of the nation or the greatness of some future project. This is just commonplace in the politics of our times. Ordinary people want to feel that they are participating in some great collective endeavor. And PR specialists give it the form of slogans. I do not see anything wrong with that, although of course in totalitarian regimes it has a different dimension and can be terrible. But don’t overdo your concerns, remembering what the difference is between the present conditions and the regimes of the kind we lived in before 1989.

ZJ: One often links Romanticism with nationalism. There is a good reason to accept the assumption that the latter sprang from the former. When you read books about Romanticism, you come across a number of terms or expressions that their authors use to characterize Romanticism. Here is a handful: genius (that is, someone who defies rules by his untrammeled will), individual spirit, nation, mythological history of a people, authenticity, creative self-expression, self-assertion, the worship of heroes, and contempt for reason.

The genius of Romantic poets notwithstanding, reading their exaltation one gets the impression that this form of emotional exhibitionism, if you want, could happen only among people who have lost their minds, who rejected Reason, as they did. They were the first ones to believe that they can create nations, a people’s soul. As Herder once wrote, “A poet is a creator of a people; he gives them a world to contemplate; he holds its soul in his hand.”

Add messianism to this, which is a consequence of such a belief, and you have a fuller picture – we no longer deal with an individual genius who has risen above others but a nation which believes – rightly or wrongly – that it has a mission, that it has been given a special task to save others, or save even a civilization itself. Since there are no clear rational criteria for judging reality, the political realm must, it seems, become an “irrational” domain operated by individuals – leaders, if you will – who believe that they can lead the nation. As it happens, sometimes things went very wrong. In view of this, could you say a few words about the connection between Romanticism and nationalism.

AW: First, Herder’s words are the words of a literary critic, who is referring not so much to the times of his own epoch, but to the beginnings of civilization. “Philosophers are the children of civilization, but the poets are its fathers” – this is how what he says should be understood. The original language of humanity was, according to Herder, poetic language. Prose and the attitude to the world based on reasoning came later – Homer preceded the birth of philosophy in Greece.

The Romanticism of the early nineteenth century was an apology for poetry understood as the original path of cognition, earlier than philosophy and science. You can partly agree that something like creative imagination actually exists and at times helps to solve some problems that seem unsolvable at first glance.

A feature of political Romanticism, as Carl Schmitt understood it, was the transfer of certain aesthetic rules and preferences to the field of policy thinking. If there is one language and one German literature, there should also be one German state. Genius can work in different fields. Thus, a brilliant poet plays a role within his own national community, etc. Under Byron’s influence, in the first half of the 19th century, extreme (that is, pre-20th-century existentialism) individualism wen hand-in-hand with dandyism, with mal du siècle, boredom (ennui), and the search for strong impressions.

All of this goes beyond nationalism; and all of it can be an object of criticism – and has been repeatedly criticized from the point of view of reason. But the Romantics were right in that man is not (and never will be) a fully rational being. If the process of modernization, which began in the West in the 17th century, is identified (as Max Weber would have it) with the process of rationalization of social life, Romanticism is an expression of rebellion against this rationalization, a rebellion rooted in the irrational characteristics of human nature. And it did not end in the 19th century. In the 1960s, it found expression in popular culture.

ZJ: Isaiah Berlin, in a series of articles on Romanticism, offered a number of insights that can explain why the currents hidden in Romanticism became pernicious.

One could distinguish several layers which created conditions that later led to the horrors of the 20th century, beginning with the sense of humiliation that stems from another nation’s cultural superiority. Such is the case of Germany vis-à-vis France, and the disruption of the old way of life, as happened in Russia under Peter the Great and, to a lesser degree, in Frederick the Great’s Prussia.

The old class becomes displaced and psychologically unfit, and creates a new synthesis, a new vision or ideology that explains and justifies resistance to forces working against the convictions and ways of life of the old class.

Finally, when a nation is at one with other forces, such as race and religion, or class and nation, we have all the conditions that can turn into a political force represented by the State. “One form of these ideas was the new image of the artist,” writes Berlin, “raised above other men not only by his genius but by his heroic readiness to live and die for the sacred vision within him… It took a more sinister form in the worship of the leader, the creator of a new social order as a work of art, the leader who molds men as the composer molds sounds and the painter colours.”

Heine, as Berlin explains, foresaw the future: “these ideologically intoxicated barbarians would turn Europe into a desert,” writes Berlin, quoting Heine, “restrained neither by fear nor greed… like early Christians, whom neither physical torture nor physical pleasure could break.”

To be sure, the legacy of Romanticism was not as morbid among the English, French, Russians or Poles as it was among the Germans. However, in the case of the Poles, and perhaps Russians, Romanticism survived as the worship of poets as national bards, men who — because of later communist oppression – filled a political void. (Mickiewicz and Slowacki, for example, are buried alongside Polish kings at Wawel Castle in Krakow). Now that Poland is a free country, is there as much room for the adoration of poets as there was before?

AW: Isaiah Berlin, as well as other well-known analysts of nationalism in English-speaking countries – Hans Kohn, Ernest Gelner, Eric Hobsbawm, Zygmunt Bauman – built the following historical sequence: romanticism – nationalism – Hitler.

All these thinkers had roots in Central Europe and brought their trauma to Anglo-American sociology from Central and Eastern Europe. It was a trauma of the persecution of Jews that ended in the Holocaust.

A similar interpretation was applied after World War II by the Communists in the German Democratic Republic. Because the roots of Nazism were said to be rooted in German Romanticism, in Jena, where the “Romantische Schule” was born, the Communists demolished part of the historic old town with the old buildings of the university and erected a gruesome modernist tower in its place, where they built a new communist university to break away from the traditions of Fichte and Novalis.

In reality, this was all much more complicated. In Poland, for example, there was a sharp conflict between the ideology of modern nationalism, represented by Roman Dmowski, and the Romantic tradition, which this nationalist and social Darwinist openly fought in his writings.

The Nazis, with whom, moreover, Polish nationalism had nothing in common, during the occupation fought fiercely against the memory of Polish culture, led by Chopin’s music and Mickiewicz’s poetry, whose monument in Krakow was demolished in August 1940. How do these facts reconcile with the theory of Romantic sources of nationalism and Nazism?

The claim that Romantic writers (but not only Romantic ones) contributed to the awakening of “nationalism,” or simply national consciousness among Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Serbs and Croats, seems obviously true. Pushkin, who wrote anti-Polish poems after the Russians suppressed the November Uprising in 1831, could also be called a Russian nationalist. So what?

The obsessive tracking down of nationalism leads only to the belief that communism was better in Eastern Europe, “threatened by nationalism.”

However, it is also true that Polish literature of the 19th century, including Romantic literature in the first place, was the main bridge leading to the assimilation of the Jewish intelligentsia in Poland.

The poetry of the Romantics, both great and smaller but equally popular, was something that could fascinate in Polish culture and which could be relatively easy to accept, along with language, regardless of any other differences. Therefore, educated Jews got Polonized in the nineteenth-century; and among writers and historians of Poland of the next century we have many of them.

ZJ: The post French Revolution world created two categories: Liberalism and Conservatism. In his essay on Alfred de Vigny, sometimes referred to as, “On Conservative and Liberal Poets” (1838), John Stuart Mill makes a list of characteristics of Conservative and Liberal literature. One of the functions of Liberal poets or writers is, as Mill states, “to lay open morbid anatomy of human nature,” which is “contrary to good taste always.”

In short, Liberalism created a new realm of literary possibilities, where vices can no longer be swept under the rug, treated as vices, but as ingredients of human nature, which should not shock us. In fact, we should find enjoyment in reading about characters who embody these vices.

What comes to mind as examples supporting Mill’s interpretation are writers such as, Balzac, Zola and Dostoevsky; but above all Ibsen; his A Doll’s House, where “sweet hypocrisy” is exposed for what it is. Yet Nora, who breaks social and moral norms, is by far a more sympathetic character than her husband, and as much as we may not like her decision. But it is impossible to feel sympathy toward her husband. Anna Karenina is another great example. And, let’s remember, Tolstoy came to regret writing it.

If Mill is right with respect to what constitutes the elements of Conservative and Liberal literature, is the liberal imagination an indisputable winner in this literary contest? Good literature is no longer a teacher of virtues and vices, has no unambiguous moral message; it is not supposed to give us moral warnings.

AW: The moral message, apart from moving emotions and satisfying the taste, was mandatory for a classical poet, of the type that reigned in all our literatures, before Jean-Jacques Rousseau, although he himself was not a poet and his La Nouvelle Heloise has a built-in moral core. Rousseau paved the way for “liberal poets,” because he recognized that it is not the individual who is morally responsible for evil. Rather, evil comes from a society corrupted by civilization. Byron’s heroes (and this is his influence), who commit crimes, are at the same time victims of the existing social order and the embodiment of interpersonal relations in this system.

Similarly, we can sympathize with Nora and Anna Karenina. It is Rousseau as a philosopher who is responsible for this, and since he is also one of the founders of liberalism, Mill’s opinion makes some sense. But literary currents are not simple equivalents of modern political ideologies. Dostoyevsky with his Demons is probably a conservative writer. But was Chateaubriand conservative or liberal? And Mickiewicz?

ZJ: Thanks to the works of Jacob Talmon (Romanticism and Revolt, 1967; Political Messianism: The Romantic Phase, 1960), of Sir Kenneth Clark (The Romantic Rebellion, where he discusses art), and of later writers such as, Adam Zamoyski (Holy Madness: Romantics, Patriots, and Revolutionaries, 1776-1871), we can form a general impression of how Romanticism influenced the way 19th century man thought. However, if you want to pinpoint what exactly Romanticism contributed to political thought, we are unlikely to have a clear answer.

However, Mill’s biographer, Nicholas Capaldi, suggested that the roots of Mill’s argument for freedom of speech can be traced to the Romantic concept of imagination, without which an argument such as this could hardly be made: why should I allow you to say something I disagree with, unless I believe that your soul, your self, can express a truth, something which reason alone – common to us and praised by Enlightenment thinkers – cannot.

Here is what Capaldi says:

“Mill will remind us that Coleridge is the English bearer of the continental tradition, and especially of German Romanticism… More specifically, Mill will argue that modern liberal culture, as best exemplified in England, cannot be adequately explained and defended except with the resources of Romantic continental thought… The French Revolution of 1789 had momentous symbolic significance for liberals everywhere. It became the symbol of the overthrow of feudalism and the dawn of a new day of freedom. Liberals as well as conservatives in Britain were later horrified by the excesses of the revolution, but the destruction of feudal privilege was looked upon as a necessary prerequisite for a truly free and responsible society.

“The stress on imagination, as opposed to intellect, is a familiar Romantic theme. It reflects the nineteenth-century rejection of the eighteenth-century’s narrow rationalism… The first consequence of this view of the primacy of imagination is the recognition that ultimate values are apprehended through imagination… One of the reasons Mill will be so adamant about opposing censorship and encouraging debate is that it is only in the imaginative re-creation, the rehashing, of the arguments that we come to understand truly the meaning of ultimate values and to make that meaning a vital part of who we are.”

Is there anything else in the realm of political ideas that belongs in the Romantic tool-box?

AW: Creative imagination as a tool for learning about the world is undoubtedly a hallmark of romantic trends all over Europe, but these trends were very diverse, and the ways of understanding them were different. If the German readings influenced Coleridge, as Professor Capaldi reminds us, it must be remembered that earlier German translations of Edmund Burke’s On the Revolution in France inspired the Schlegel brothers and their entire generation in Germany. Thus, the exchange between England and the Continent was mutual. Liberalism is older than the Romanticism, as is republicanism, which is important to Poles. So, there were liberal and conservative romantics, and the great Polish romantic, Juliusz Słowacki, described himself as “republican in spirit.”

Hence Mill’s brilliant thought that the genesis of the idea of freedom of speech must be the Romantic idea of imagination, may be true in some cases, but historically speaking not at all. In short, the specific influence of Romanticism on the understanding of politics may consist in giving politics an eschatological dimension (messianism), in referring to pre-philosophical national traditions as an expression of the community spirit, in the observation that the poet has a special type of power – over the work he creates and over their recipients – and that authority should have such a character in general, and that the poets thus should be the charismatic leaders of the nation.

Let me add that in the 19th century the cult of poets (Mickiewicz, Słowacki, Krasiński) gained political significance in Poland; and in the 20th century, in popular culture, we are dealing with something analogous, when, for example, Bono from the band U2 speaks about politics, and all world agencies keep repeating what he utters.

ZJ: Nihilism which we’ve mentioned was not the only social worry of the second half of the 20th century. One can argue that hedonism is as pernicious as nihilism. I would like to invoke another song by Queen, “I Want It All;”

I’m a man with a one track mind,

So much to do in one life time (people do you hear me)

Not a man for compromise and where’s and why’s and living lies

So I’m living it all, yes I’m living it all,

And I’m giving it all, and I’m giving it all,

It ain’t much I’m asking, if you want the truth,

Here’s to the future, hear the cry of youth,

I want it all, I want it all, I want it all, and I want it now,

I want it all, I want it all, I want it all, and I want it now.

Each time I hear it, I think that this song is the utmost expression of hedonism, which is a product of an infantile mind. Only children want it all and want it now. It is their perception of time which makes them want to satisfy their wants and needs right away. They want immediate gratification. Adults know that you can’t have it now. But there are more serious problems that go beyond the song. First, immediate gratification of all desires would be deadly for moral discipline. Liberalism is the only political philosophy that tells us that we have a right to satisfy our wants.

Would you agree that this kind of thinking – nihilism mixed with hedonism – is what our world today is made up of.

AW: I don’t know if this song is so clearly about a hedonistic attitude. Your question about modern hedonism is much more serious. Westerners, when they believed in God, wanted the salvation of their souls – eternal life beyond this world. Then, under the influence of humanism and the Enlightenment, happiness became their goal. Happiness on earth, not in the afterlife. But that happiness did not have to be immediate; it could be the achievement of some ambitious goal or perfection (per aspera ad astra), or the pursuit of perfection itself. In the end, happiness was equated with pleasure, which was independently invented by the Marquis de Sade and 19th-century Liberals. It appealed to simple people, because pleasure is not some abstract ideal, but something concrete, sensually experimental. And why shouldn’t we experience it too, here and now?

This ethical turn, which took place in the West in the 19th century, seems to be something permanently present in people’s attitudes to life today. In the second half of the 20th century, it coincided with the triumph of technology and capitalism, which turned out to be capable of producing an inexhaustible amount of consumer goods; that is, those that both satisfy our needs and provide us pleasure. Since constant enjoyment has become easy and readily available for all, a new hedonism has indeed spread in the society of “well-being.” It is based on the pursuit of immediate satisfaction of our whims. And after satisfying them, new needs appear, which are also immediately satisfied, and so on.

Mandeville noted, as early as the 18th century, that people who are accustomed to luxury buy more things that, objectively speaking, they could live without. In this way, which may not be beneficial to themselves in the long run, they nevertheless make money for the craftsmen and merchants, who supply them with these luxuries.

So, the need for pleasure drives the economy to work. The capitalism of our time creates these artificial needs in people in a systemic way, stimulating them through advertising, and by presenting the model of a human being present in pop culture, whose success lies in the fact that he has everything, here and now.

The contemporary ideal image, spread in commercials, in television series about the lives of millionaires, in photo essays about celebrities, is therefore the image of a hedonist – an ideal, i.e., the ever-insatiable consumer. So, hedonism drives sales – that is, the entire economy – and thus promotes it.

The problem is that all civilizations of the past that fell into this trap collapsed. While we can make our toys endlessly, we are not in danger of collapsing because of the wear and tear of our accumulated goods – waste was condemned by moralistic people since antiquity, but that doesn’t help.

The process of ceaselessly satisfying an appetite that is continuously, artificially stimulated, is destructive in itself. We need stronger and stronger stimuli, bigger and bigger doses of new stimulants. And in the end, they kill us – like the drugs that have killed a legion of stars of modern pop culture.

The biggest problem of any civilization, at some point, ceases to be the struggle with nature and hostile tribes, and it becomes the need to fight our own weaknesses, which come to us as a result of our own success. We are safe, rich; we have free time – and we don’t know what to do with all of this. This is when the self-destructive process begins. Giambattista Vico already knew that.

ZJ: Let me go back to what you said about the democratization of language, and that the success of Romanticism lies in using the language people use and emotions that they feel. As always, what at the beginning sounds like a well-intentioned idea, later can have unintended consequences. We talked about John Lennon and Queen, nihilism, and hedonism. One could still argue that they translated high-brow philosophical ideas into language that the ordinary people could understand as their own. Neither Lennon nor Queen are guilty; they just “expressed,” in the form of popular music, what philosophers said decades earlier.

Now, 50-60 years later, it is not Romanticism or Existentialism which stand behind the new trends in music. It is the naked, ugly reality of the street, to which once high-brow philosophy led society. In America it is called rap. Rap spread everywhere like a tsunami. It started as a form of expression of the feelings – or more likely resentment – of the destitute, undereducated Black segment of American population. However, because of its vulgarity and outright racism it is listened, for the most part, by Blacks, and it terrifies most of the Whites. Yet the liberal media bow to it.

One of the Founding Fathers of rap, JZ, is a musical icon, interviewed on National Public Radio and television in the US. University professors organize courses about JZ. When you listen to his public pronouncements you get the feeling that rap is not music but a form of mental imprisonment of someone who never grew up. Do you have an explanation as to what happened and why? Is rap the last phase of the Romantic rebellion led by adult children, like JZ?

AW: Paradoxically, I agree with this last sentence, at least to a certain extent. Yes, I can see that music videos of this type tend to be soft pornography and praise the lives of gangsters – obviously I’m not attracted to the stupidity of it all. There are also nobler forms of this music; but I do not follow or analyze them either. Both rap and hip-hop are artistic styles with their own rules and structure. I can imagine a masterpiece in this genre, although I cannot name it. Perhaps it is because of my own ignorance, or perhaps a rap-style masterpiece has never been created and will never be.

But since rap exists as a separate style – the existence of outstanding songs of this type is also possible and probable. In Poland, where all Anglo-American musical styles are imitated, the band Kaliber 44 enjoyed a short-lived fame some time ago, whose young soloist was considered a genius; but his life was short, because he killed himself jumping, out of a window under the influence of drugs.

This is hard to approve of in any way, but the interpretation you are proposing here also seems possible. Rap is a peculiar rhythm that is based on the intonation of individual sentences and crossed with relatively regular versification. The content of the rapper’s monologue is important; the music has a secondary role; it accompanies the recitation of the text and emphasizes its meaning. These are features that are well known from the folklore of bygone eras.

Thus, the romantic theory of nature poetry, which is born spontaneously among simple people, lacking knowledge of the conventions and rules of official art, fits it. Rap with its style and place of birth (in the dangerous neighborhoods of New York) fits well with this romantic theory.

Besides (probably) rap performers cannot be suspected of illustrating Sartre’s theses. So, maybe this is not a simplified adaptation of high culture, but a real inflow from below – the music of the roots? On the other hand, it is also not ordinary folklore, because in the process of producing recordings, the simplicity of style and the primitiveness of picture-suggestions are combined with technical and technological refinement.

ZJ: Going back to your remark about the use of ordinary language by the Romantics. Is this the beginning of the process which led to the birth of what we call “popular culture” – as opposed to High Culture? Today no one uses the distinction between High and Low/popular culture. The educational system in Western countries is structured in a way that what belonged to the Treasure of Western Culture or Kultur, is no longer taught. It is at best tolerated. The last attempt at defending High Culture was probably T.S. Eliot’s Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1959). Do you see where we are today as a result and the end of cultural mutation of Romanticism?

AW: I prefer to think of Romanticism and pop-culture, and, more precisely, of the specific elements of these different, certainly broad and difficult to define phenomena, not as mutations, but as cultural modalities. In similar cultural phenomena, the actualization of similar potentials, constantly inherent in human nature, takes place. Cultural updates are historical and the potentialities of nature’s people are unchanged.

ZJ: Thank you Professor Wasko for this wonderful interview.

Andrzej Waśko is professor of Polish Literature at the Jagiellonian University, Krakow. He is the author of Romantic Sarmatism, History According to Poets, Zygmunt Krasinski, Democracy Without Roots, Outside the System, and On Literary Education. The former Vice-Minister of Education, he is curretnly the editor-in-chief of the conservative bimonthly magazine Arcana and is presently Adviser to Polish President Andrzej Duda.

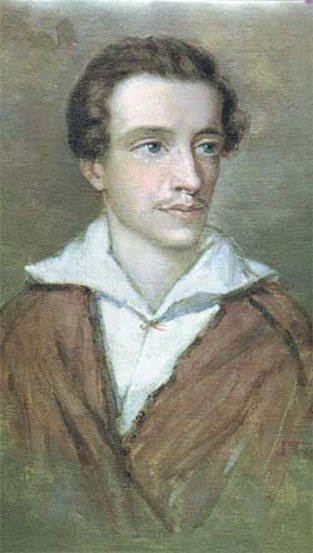

The image shows, “Sielanka (An Idyll),” by Józef Chełmoński, painted in 1885.