“The main thing, from the point of view of existence in history, is not to have success; success never lasts. But it is rather to have been there, to have been present; and that is indelible.” The life of Jacques Maritain is a long struggle of presence, a vocation illustrated by these words from his work Pour une philosophie de l’histoire (For a Philosophy of History). An existence that does not seek laurel wreaths, which always wither, but one which refuses to withdraw from historical events—thus defining for the rest of the contemporary era the role of the Christian intellectual, against all Nietzschean criticism. It is a question of being in the world, of respiritualizing the world.

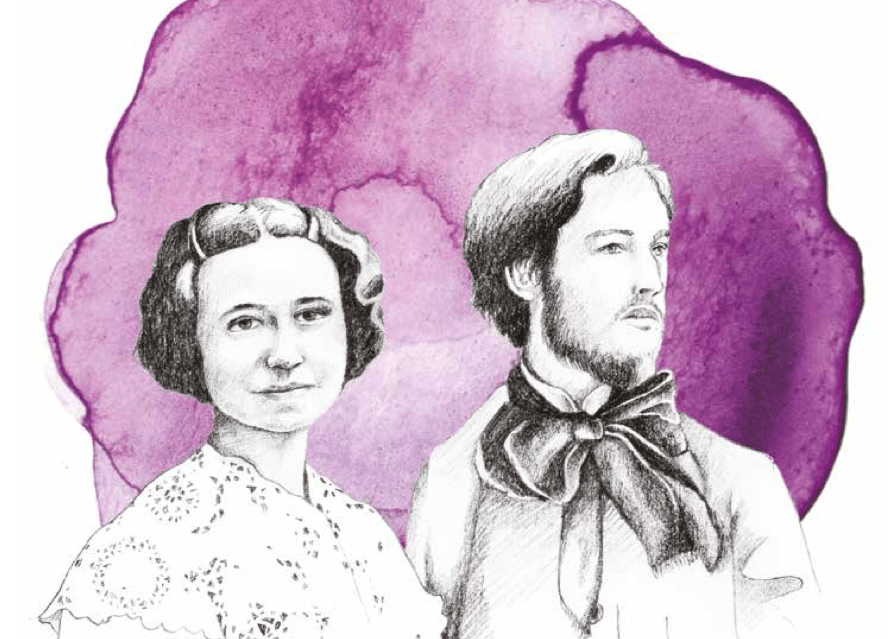

This profession of living, Jacques Maritain did not accomplish it alone. Many friends joined him; many fellow travelers brought their contribution to it. But there is only one person who was with him from the beginning: “I have a destiny, and that is already wonderful. For destiny is the unity, the usefulness and the beauty of life. And my destiny is not to be my own. God has given Jacques and me the same destiny, and as a viaticum a unique and marvelous warmth.” The presence of Raissa, as evidenced by the words of his Diary, cannot be erased, because there can be no Maritanian work without the common destiny of this couple.

A Couple In Search Of The Absolute (1902-1906)

When they met in the corridors of the Sorbonne, it was the fading brilliance of their two atrophied intellects that brought them together. Materialism, positivism, nascent sociology, Durkheim and Lévy-Bruhl had dried up their spirit; they were left with a reason proper to ratiocinations and to some scientific inductions. Both sought to understand being; but Jacques devoted himself to militancy, while Raïssa was rapt in a mysticism without object.

Hit hard by Cartesian reductionism, reduced to only matter, they decided to grant themselves one year of research, after which, if their thirsts remained unquenched, they would choose death: “Our perfect agreement, our own happiness, all the sweetness of the world, all the art of men could not make us admit without reason—in some sense that one may take the expression—the misery, the misfortune, the evil of the men. Either the justification of the world was possible and it could not be done without true knowledge; or life was not worth a moment’s attention.”

Already, we can see in this gesture, the seeds of their future thinking—a concern for the world, for this world and a need to illuminate it with an objective and absolute light.

It was Charles Péguy, friend of Jacques Maritain’s mother, who, seeing the despair of this couple that he loved, led them to the lessons of Bergson. “God’s pity made us find Henri Bergson.” wrote Raïssa. In the assembly of the pupils, the joy was reborn, and the beginnings of a true knowledge appeared. Plotinus, Plato, Pascal, the history of philosophy opened to them, and the history of mysticism.

But Bergson and his philosophy were not enough. Married in 1904, they discovered shortly afterwards Léon Bloy’s book, La Femme pauvre. Suddenly, within a year, they opened up to the Christian faith. On June 11, 1906, they were baptized and the “ungrateful beggar” was their godfather. For them, it was no longer a question of knowing or leaving the world, but of being saints.

The Formative Years (1906-1909)

Jacques’ studies led them to Germany, where Raïssa, forced by illness to live indoors, never stopped reading and praying. Guided by the Dominican Father Humbert Clérissac, she discovered the writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas. This time, intelligence and faith were united; the soul, the body and the spirit can be expressed. There is a realism that brings reflection closer to being, and at the same time, a spiritual depth that elevates the whole of Creation. There is also an answer to evil, an explanation of human freedom. And above all, there is an eternal and objective truth that is only waiting to be revived to enter the 20th century.

For, before Jacques and Raissa Maritain fell in love with Thomism, this philosophy remained contained in the abbeys and seminaries where it was often diluted in very scholastic manuals, in the pejorative sense of the term. The Dominicans struggled to begin a renewal. However, convinced and enthusiastic about Saint Thomas, the young couple set out to expunge all the knowledge that was not suitable for an authentic Thomism. From 1909 to 1913, Bergson’s work was reread, criticized and corrected.

Demanding, zealous, intransigent, the Maritains penetrated into the history of their century, armed with a secular doctrine. And it is not as scholars that they awakened medieval thought from its slumber: “If we go to look for our conceptual weapons in the arsenal of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, it is not to return to ancient Greece nor to the Middle Ages. We believe that it is a kind of blasphemy against the government of God in history to want to return to a past state, and that there is an organic growth of both the Church and the world. Therefore, the task that is imposed on the Christian is, we believe, to rescue the distressed truths, as Chesterton said, that four centuries of anthropocentric humanism have disfigured, and to reconcile them with the higher truths disregarded by this humanism, and to return them to the Truth in person whose voice faith hears” (De Bergson à Thomas d’Aquin, “Aspects contemporains”).

What History Demands (1909-1939)

The Maritains’ coming to Thomism is thus a coming into the history of their time. Accompanied by Raissa’s sister, Véra Oumansov, they settled in Versailles and then in Meudon in 1923, opening the doors of their houses to all the disoriented, the refugees of the spirit, the intellectuals without faith, the religious seeking rest, the artists looking for a new delight. We can no longer count the men and women who, in the Maritains’ salon, groped their way to God.

In the whirlwind of the Dada and Surrealist periods, as history accelerated, as Russia entered into revolution and Europe was torn apart, Jacques and Raïssa passed on the lights of Thomism. It was the time of the first speculative writings and manuals, Eléments de philosophie (Elements of Philosophy) in 1920, Réflexions sur l’intelligence (Reflections on Intelligence) in 1924, and especially Distinguer pour unir ou Les degrés du savoir (Distinguishing to Unite or the Degrees of Knowledge) in 1932, and his most important work of pure philosophy, La philosophie morale (Moral philosophy) in 1960. Anxious not to let the artistic revolution pass by that the war gave birth to, Jacques wrote Art et scolastique (Art and Scholasticism) in 1920: “at a time when all felt the need to leave the immense intellectual disarray inherited from the XIXth century, and to find again the spiritual conditions of honest work.”

The immense advantage of the Thomism of the Maritains was that it did not place them above the world. Their philosophy was not built in a closed system which they tried to apply to the world. It was being which was first in any reflection. Thus, when Jacques wrote Antimoderne in 1922, he criticized the excesses of his time, not to lead it back to the old world, but to lead it towards a new destiny: “What I call here antimodern, could have just as well been called ultramodern. It is well known, in fact, that Catholicism is as anti-modern by its immutable attachment to tradition as it is ultramodern by its boldness in adapting to the new conditions arising in the life of the world.”

This sentence testifies to the primary will of the Maritain couple—to incarnate, in the world that is contemporary to them, a truth that they consider as eternal. It was therefore important to develop instruments and arguments adapted to the time in which they were situated. It was the history of men; it was the First World War; the irruption of Marxism-Leninism. It was scientific adoration; the despair of their fellow men that pushed them to philosophize. In this, they mixed a true quest for holiness with their quest for the intelligible; charity guided the construction of their thought.

The events leading to the development of their philosophy, the condemnation of the Action Française in 1926 by Pope Pius XI, required Jacques Maritain to enter the political field. Close to Charles Maurras, Jacques offered himself as an intermediary between the pope and the theologians of the royalist movement. Nothing helped, not even the writing of Primauté du spirituel (Primacy of the Spiritual) in 1927. Political thought occupied the soul of the maurrassiens; the spiritual authority of the pontiff was not recognized. The Maritains reaffirmed their obedience to the Church and consummated the divorce with a fringe of French Catholics. Jacques lost the friendship of Bainville and Massis; he was only a “traitor” for Maurras, a “muddied jurisconsult.”

Intellectual itinerary was strewn with obstacles, with friendships that were linked and unlinked. The Spanish War, the Italian-Ethiopian conflict, the rise of Fascism in Italy, Nazism in Germany, the growing anti-Semitism, Jacques confronted all these subjects one by one. Too far to the right for the left, too far to the left for the right, he was scorned and judged. In 1934, when France was on the verge of civil war, he and fifty-two Catholic intellectuals, all lay people, published a manifesto, Pour le bien commun (For the Common Good). The approach was clear: to think of a third way between fascism and communism. This third way, the personalist way, was presented in 1936 in Humanisme intégral. Warning against totalitarian delusions, he repeated it in 1937 against Franco with De la guerre sainte, and the publication the same year of L’impossible antisémitisme.

In his Lettre sur l’indépendance (Letter on independence) in 1935, Maritain exposed his own approach the Christian intellectual must guide the temporal city towards a healthy Christian policy, but he cannot belong to any party: “To be neither of the right nor of the left means that one intends to keep one’s reason.”

To Democracy And The Church (1940-1948)

The defeat of 1940 caught Jacques, Raissa and Vera in the United States. Jacques had committed himself to teaching in the United States and would remain there for twenty years. This exile during the Occupation brought him closer to many intellectuals, and the trio recreated the atmosphere of the Thomist circles of Meudon. Pressed by the letters he received, conscious of the anguish that gripped Europe, Jacques wrote A travers le désastre (Through the Disaster) in 1941, which was passed along like a viaticum—the hope of a Christian renewal must not die. Raïssa, for her part, undertook to recount the history of the Grandes Amitiés (1949) of the inter-war period. This book was part of an effort on the other side of the Atlantic to support, to remember all the things, this time of light, and it was the assurance of a spiritual vocation of Christians in their time.

For his students, Jacques explained again the democratic principles, and wrote Les Droits de l’homme et la loi naturelle (1942), Christianisme et démocratie (1943). Thomism was applied to democratic thought that Maritain explored within American society.

The metaphysician Maritain seemed to have disappeared, carried away by the turmoil of his time in a political war. As the hour of the Liberation sounded, and he finally thought of pursuing his speculative work, General de Gaulle appointed him French ambassador to the Holy See. Of an exemplary obedience, Maritain fulfilled his role during the three years. In the corridors of the Vatican, he made friends with Cardinal Giovanni Batista Montini, the future Paul VI, who was committed to the personalist theses as well as to “integral humanism.” The Maritains, by their mere presence, distilled the Thomism that inhabited them at the top of the institutional Church. At the Taverna Palace, the ambassador’s residence, politicians, diplomats, clerics and laity were invited to the discussions. And the Maritains held their ground, assisted by the tireless Vera Oumansov.

The American Years (1948-1960)

The United States offered Jacques the security necessary for his intellectual life; and the family returned to Princeton in 1948. It is regrettable that the Maritains were not retained in France, that they did not fight head-on against the existentialism of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. But American universities seem to have allowed another historical moment: the transmission of a Thomist heritage. In Toronto, the philosopher Etienne Gilson, a fellow traveler of the Maritains, had participated since 1929 in the establishment of a Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies, and Thomism became American.

Moreover, it was also a time of assessment for Jacques, who wrote Pour une philosophie de l’histoire in 1957. This work testifies to an awareness of the importance for the Christian of a true knowledge of history and especially of the history that is being made. Sounding like a response to the positions taken by his Christian contemporaries during the great events of the 20th century, Maritain writes: “The philosophy of history has consequences for our action. In my opinion, many of the mistakes we are making in social and political life today are the result of the fact that, while we have many true principles (at least we hope so), we do not always know how to apply them intelligently.”

Good Christian intentions, great ideas that only find bad applications, the Second Vatican Council came to legitimize this assertion of Maritain. But, before the Council, there was the death of Raissa, on November 4, 1960: “Like a fortunate ship/ Which returns to port with its cargo intact/ I will approach heaven with a transfigured heart/ Carrying human and unblemished offerings.” She who had made her illness a prayer, a work of love, she who had reread and revised all of Jacques’ texts, she who had written and described the anguish of living far from God, at once the wife, the counselor, the soul and the breath, died before him. Vera having died the year before, Jacques left the United States, alone, wanting to finish his philosophical work in silence.

“What Does Maritain Think?” (1960-1973)

Living with the Little Brothers of Jesus, not far from Toulouse, the philosopher continued his work. He desired monastic quietude, and favored contemplative activity, editing the Journal de Raïssa. But the “silence with God” of his deceased wife was not the vocation of the old philosopher. Not sparing his venerable age, Pope Paul VI asked him to intervene, in 1965, in the elaboration of several points of doctrine related to the conciliar declarations. At the closing of the Council, the Pope symbolically handed over the message “to the men of thought and science” to Maritain.

But it was the post-council period that mobilized the forces of the “old layman without a mandate.” Antimodern, ultramodern, resolutely attached to clarifying the thought of his time, Jacques wrote Le Paysan de la Garonne (1966) where with all the bonhomie of a fraternal correction, he attacked the various interpretations of the Council. Catholics got into a tussle; we wondered what Maritain thought; we would have preferred not to know. Thanks also abounded: “Yes, you are breaking the mold; you are letting the salubrious wind of the Spirit pass by. You dare to write: Spiritual revolution, soul, spirit, when many priests remain peculiar and bizarre, no longer finding beauty in the simple word that dry up in speaking, the imagination cooled down. In short, they shirk, or limit themselves to the world,” wrote the young Dominique de Roux to him in a letter in 1967.

Until his last breath, Maritain kept this vitality of thought, this clairvoyance and this refusal to limit himself to the world. Because, it is there, the Aristotelian middle ground, and it is with Maritain that this role of the Christian in the world takes shape: to be in the world and never to be limited to the world. This “new fire,” this spiritual ardor was only waiting to penetrate the Earth, to revolt against the Prince of this World that Raissa described in her work. And Jacques added, very soberly: “It is that the work undertaken by us consisted in reality—like any work which tries to open the world of the profane culture, art, poetry, philosophy, to the energies of the Christian ferment–to attack the devil on his own grounds.”

Baudouin de Guillebon studies philosophy and writes for La Nef, through whose courtesy, we bring this article.