Over eight centuries before Franklin D. Roosevelt articulated his “Four Freedoms,” a shorter and much better list of freedoms was elucidated by the young abbot of the new monastery of Clairvaux, one Bernard by name.

In his work, On Grace and Free Choice (De Gratia et libero arbitrio), Saint Bernard (1090-1153) distinguished three kinds of freedom: of nature, of grace, and of glory. The first is freedom from necessity; the second, from sin; and the third, from suffering. All three concern man’s inner life, where all true freedom resides, rather than extrinsic factors. (For a timely example of what I mean by “extrinsic factors,” we might consider freedom from external compulsion to receive an unethically sourced, unnecessary, and ineffective vaccine against an illness that 99.7% of people who contract it survive.) For us moderns, like Roosevelt, the tendency is to locate freedom outside of ourselves, but that is not what Saint Bernard had in mind. Real freedom, I repeat, is an interior reality, and all three of these freedoms are interior.

The Calvinists and Lutherans, who exaggerated the effects of the Fall, denied that man’s will is free. They would have done well to read Saint Bernard, who based his argumentation solidly on Holy Scripture. So, too, do modern schools of psychological determinism deny — or at least detract from — the freedom of the will. But Saint Bernard, writing with great philosophical certitude and liberty, shows that the will by its very nature is free.

This innate freedom of the will, in addition to our intellect, is what makes us in the image and likeness of God, and the Master of Clairvaux notes that this first freedom has nothing to do with whether we are good or bad: “Freedom from necessity belongs alike to God and to every rational creature, good or bad.” This freedom, which makes our actions “voluntary,” is contrasted with that necessity of which brute beasts are possessed in all their actions. In dogs and cats, and all the rest of non-rational animals, there are no voluntary or free acts. They act by an interior compulsion to do what they do. Without having an intellect and a will, non-rational animals live exclusively on the level of the senses and the irascible and concupisciple appetites. We, too, have those faculties, but our intellect and will tower over them and make our acts human acts and therefore voluntary and free acts. As the Cistercian Doctor puts it negatively, “What is done by necessity does not derive from the will and vice versa.”

For clarity, I should note here that there are acts that men do that are not voluntary and therefore not free. These are things we have in common with the beasts, like respiration, digestion, and the myriad other activities our bodies perform every moment to keep us alive and functioning at the level of mere sentient activity. Philosophers call such acts “actus hominis” (acts of a man) as distinguished from “actus humanus” (human acts). “Human” here means rational and volitional.

The following sentence from On Grace and Free Choice may be long and need to be read two or three times, but it is very illuminating of the truth concerning man’s will being free and the consequent moral responsibility we all shoulder by virtue of our freely chosen acts:

Only the will, then, since, by reason of its innate freedom, it can be compelled by no force or necessity to dissent from itself, or to consent in any matter in spite of itself, makes a creature righteous or unrighteous, capable and deserving of happiness or of sorrow, insofar as it shall have consented to righteousness or unrighteousness. [All excerpts here are from the Cistercian Publications edition of the work, translated by Daniel O’Donolan, OSCO.]

The truth that “sin is in the will,” is an immediate conclusion from what Saint Bernard writes here. While we might be externally influenced, threatened, cajoled, directed, encouraged, etc., in our will we always remain radically free. This is an anthropological or psychological fact that follows from our very nature as it was created by God, prescinding from the Fall. It is the basis of all merit and culpability and, therefore, of the notions of reward and punishment.

Over and above this first freedom, the innate freedom of nature, are the two other freedoms (that from sin, and that from sorrow) which are not natural endowments but supernatural gifts.

Saint Bernard explains that freedom from sin is what Saint Paul described when he wrote, “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom” (2 Cor. 3:17). This second freedom is not innate in us, but results from grace, and stands in contrast — so the Abbot of Clairvaux notes — to that slavery to sin that the Holy Apostle describes elsewhere: “For when you were the servants of sin, you were free men to justice. [Saint Paul is ironically contrasting “slavery to sin” and “slavery to God (or justice)”. Being “free men to justice” means being “liberated” from God’s holiness or righteousness. This is a false and damning freedom.] … But now being made free from sin, and become servants to God, you have your fruit unto sanctification, and the end life everlasting” (Rom. 6:20, 22).

Citing Our Lord saying, “If therefore the son shall make you free, you shall be free indeed” (John 8:36), Saint Bernard tells us:

He meant that even free choice stands in need of a liberator, but one, of course, who would set it free, not from necessity which was quite unknown to it since this pertains to the will, but rather from sin, into which it has fallen both freely and willingly, and also from the penalty of sin which it carelessly incurred and has unwillingly borne.

We ought not quickly pass over the profound thought that “even free choice stands in need of a liberator.” The words are beautiful, yes, but there is more than mere aesthetics here. Our free will, after the Fall, contracted the defect Saint Thomas calls “malice,” and needs to be saved from it, or freed. The liberator in question is, of course, that Man who knew no sin, and who always was and always remains absolutely free from sin. Citing Psalm 87:6, Saint Bernard calls Christ, “[He who] alone of all men was made free among the dead; free, that is, from sin in the midst of sinners.”

Concerning this “second freedom” — freedom from sin — the Mellifluous Doctor eloquently addresses the question of good will versus bad will in words that should encourage us:

When a person complains and says: “I wish I could have a good will, but I just can’t manage it,” this in no way argues against the freedom [from necessity, the “first freedom”] of which we have been speaking, as if the will thus suffered violence or were subject to necessity. Rather is he witnessing to the fact that he lacks that freedom which is called freedom from sin. Because, whoever wants to have a good will proves thereby that he has a will, since his desire is aimed at good only through his will. And if he finds himself unable to have a good will whereas he really wants to, then this is because he feels freedom is lacking in him, freedom namely from sin, by which it pains him that his will is oppressed, though not suppressed. Indeed it is more than likely that, since he wants to have a good will, he does, in fact, to some extent, have it. What he wants is good, and he could hardly want good otherwise than by means of good will; just as he could want evil only by a bad will. When we desire good, then our will is good; when evil, evil. In either case, there is will; and everywhere freedom; necessity yields to will. But if we are unable to do what we will, we feel that freedom itself is somehow captive to sin, or that it is unhappy, not that it is lost.

The words here rendered “oppressed, though not suppressed” are premi non perimi, and are difficult to translate, but the sense is that, though the will is in part impaired (by sin), it is not rendered powerless. Moral theologians of later ages would develop in detail the Church’s accepted moral doctrine concerning the diminishing of the freedom of the will by habitual sin, yet the notion is here in seminal form in Saint Bernard. The doctrine here explained is very consoling. If we will the good but yet sin, there is still some good in us. The remedy is grace, the major burden of Saint Bernard’s book, which is there for us if we but ask of it. For that reason and others, in the practical order, prayer is the main point of contact between God’s grace and our free will. It opens us to the remedy our will needs. Without prayer, even the sacraments will avail us but little because we lack the necessary dispositions to receive the remedies they contain.

Concerning the “third freedom,” that from suffering, or, as he also calls it, “the freedom of glory,” the Cistercian abbot is clear that it is not for this life, but the next, for “it is reserved for us in our homeland” of Heaven:

There is also a freedom from sorrow, of which the Apostle again says: “The creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and obtain the glorious liberty of the children of God” [Rom. 8:21]. But would anyone in this mortal condition dare arrogate to himself even this kind of freedom?

He further adds that, by this third freedom,

[W]e are raised up to glory, a perfect creature in the Spirit. [And] … by it, we cast down death itself. … Finally, by the last-named, in our own more perfect submission to ourselves through victory over corruption and death — when, that is, death shall be last of all destroyed [1 Cor. 15:26] — we will pass over into the glorious freedom of the sons of God [Rom. 8:21], the freedom by which Christ will set us free, when he delivers us as a kingdom to God the Father” [Cf. 1 Cor. 15:24].

We are living in a time when our civic freedoms seem imperiled by an emerging biometric security state, an Orwellian oligarchic kleptocracy that demands we give up our freedoms for the lying promises of safety, security, and now health. In the midst of these mendacious statist shenanigans — so obvious to those not drinking the Kool-Aid of mainstream media and Big Tech — let us more and more cherish and cling to our real freedoms which are ours by Baptism and the giving of the Holy Ghost… and which no man can take from us.

Brother André Marie is Prior of St. Benedict Center, an apostolate of the Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Richmond New Hampshire. He does a weekly Internet Radio show, Reconquest, which airs on the Veritas Radio Network’s Crusade Channel.

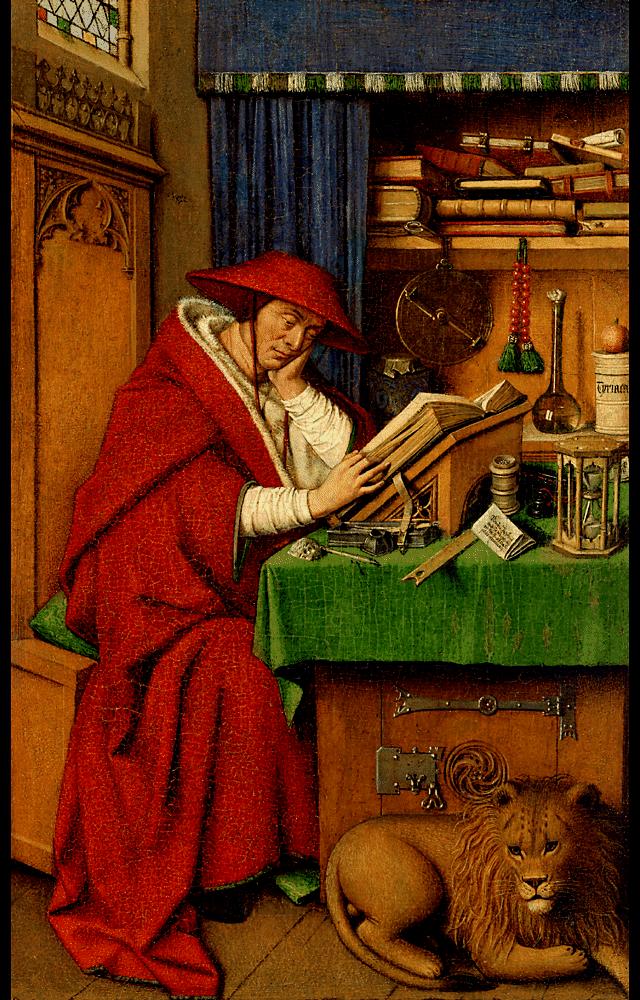

The featured image shows, “Apparition of the Virgin to St Bernard,” by Filippino Lippi, painted in 1486.