I. France, The Anti-Empire

Any attempt to build a metaphysics of nations is doomed to failure. There remains, however, the possibility of affirming a definition of the intimate affinity of nations with certain political forms based on their historical biography. In the case of France, however, this biography arises historically from a truly disconcerting paradox. France, the only nation that retains the name of the Germanic tribe that restored the Empire in Europe, has been the nation that has fought the most. According to Erwin von Lohausen: “Among the various powers that, one by one, were facing the Habsburg Empire, France became, more and more after Louis XI, the soul of the rebellion. While French royalty had the same origins as the German Empire, France was, by nature, the anti-Empire.”

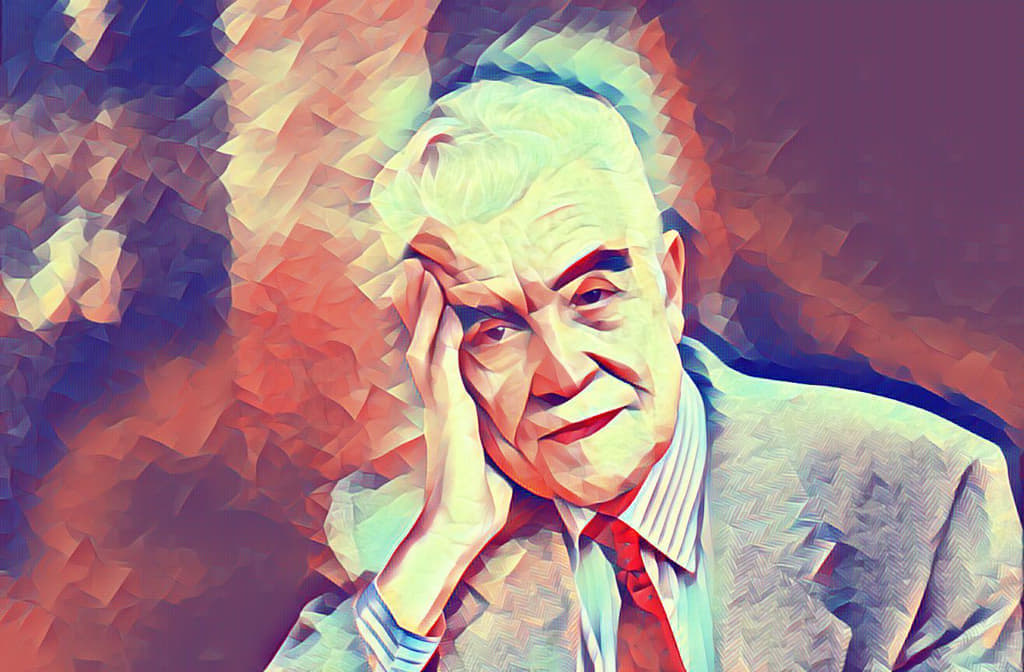

Austrian General Erwin von Lohausen, one of the great experts in geopolitics of the twentieth-century, a veteran of World War II under Rommel, insisted in his analyzes that the meaning, and the relationship with space, of the necessities and the passions of people are engines of world history that no religion or ideology can counteract.

These considerations may seem shocking when applied to the definition of the historical personality of the French nation. Has it not been the country that has poured forth with genuine conviction (at least in its declarations) at the service of a universalist mission, be it religious (the Crusades) or secular (the Rights of Man)? And has not this nation also been one to never hesitate to use these “sacred causes” (to take up the expression of Michael Burleigh) to “profess a fierce national egoism” and a “prejudice for the Fatherland?” It is not easy to find any other European people better able to bear the heavy burden of an impossible symbiosis between sacred universalism and chauvinistic nationalism. Hence the German geopolitical analysis of authors like von Lohausen is so valuable.

It was scholars like these who pointed out the striking freedom of France in choosing its own historical causes in comparison with other nations, conditioned by a geography that limited its scope for action in contrast to the comfortable French geopolitical position: “For German geopolitical scientists, France, because of its geographic situation, enjoys a freedom of action that neither Spain, nor Italy, nor Germany ever had. Historically, these three countries had to directly confront the Saracens, the Slavs and the Magyars. They could only act in relation to their needs. France, however, had the freedom to really choose its policy, to proclaim the Crusades and the Rights of Man.”

Indeed, far from seeing in it an insurmountable opposition, perhaps it is its privileged geostrategic position that explains to a large extent France’s historical fondness for leading the great sacred causes of each era and serving them, by attending first to the interests marked by the politics of national individualism. In France, the universal missions are always framed within the friend-foe political duality.

The peculiar historical configuration of the French identity is one of the most relevant keys to understanding the success with which it confronted empires politically, without ceasing to defend, on paper, the sacred causes with which the latter justified the legitimacy of their hegemony. The first-born daughter of the Church was the Catholic nation that most effectively fought the Holy Roman Empire. Thanks to the testimony of France, we better understand the ineradicable political dimension of the so-called “wars of religion.” Not even in that historical context, of mystical fervor in defense of the faith, could the friend-foe dialectic be translated without historical falsification into any other kind of completely crystalline moral or religious duality. There was France and the policy of its kings to deny it.

Once again, France “chose” its policy with full freedom; and did so against the empire and in the name of the same religious cause. The empire never had a fiercer enemy, because not only did France frustrate its expectations of supremacy with the strength of its armies, but France did so with the authority of its bishops and cardinals, as well as the countless Popes affected by the efforts of her first-born daughter. Although separated very soon from the imperial destiny of Charlemagne, France nevertheless preserved the genetic and foundational mark of a divine mission in “mimetic” competition with the empire. It is perhaps one of the most defining features of France’s identity.

Who is to blame for the French superiority complex, the self-assumed grandeur de la fille aînée de l’Église (“greatness of the first daughter of the Church”)? Psychologists speak of the “child emperor” syndrome to refer to children who end up dominating their parents. It is a curious formula since, in the case of France, the syndrome paradoxically afflicted the nation called to fight the empire pushed by the primogeniture privilege of its affiliation with the Church.

And just as psychologists point to the responsibility of parental education to understand the character formation of these imperial children, so in our case we must also point to the parents of France (the Empire of Charlemagne and the Catholic Church) as mainly responsible for an education conducive to the affirmation of a national pride based on the supreme legitimacy of a divine mission. “The bishops made France as bees make the hive,” wrote Joseph de Maistre. This observation is not without value but even it seems too restrictive. It was the entire Church that fed the religious vanity of the French nation. It was the Church that shaped it, that nurtured it, while continuing to excite and glorify with its education the achievements and conquests of its favorite daughter.

II. A State Against The Empire: Richelieu, Founder Of Modern Europe

A large part of the tensions of the history and identity of France are attuned to the aporia of the political form with which it has wanted to serve its universal mission. The State has been a particularist tool that has determined a good part of the historical dynamics that explain the French opposition to the empire. The victory of France in the seventeenth-century against the Spanish hegemony was also the victory of the state political form over the imperial political form.

Where are the historical roots of this crossroads to be located? The Colombian, Nicolás Gómez Dávila, wrote: “The modern State is the transformation of the apparatus that society has developed for its defense into an autonomous organism that exploits it.” France developed an apparatus for its defense. And the architect of that apparatus was Cardinal Richelieu.

The key to understanding the genesis of this apparatus is found, in full harmony with the Hobbesian thesis, in the civil war that bled a France increasingly divided into religious, political and social factions. As Philippe Erlanger, Richelieu’s biographer, recounts: ”No one was a greater creator than Armand du Plessis. When he took the nation in hand, France was not just a nation adrift; total anarchy devoured it. Its weakness in the face of other powers made it a kind of vacant good, an almost virtual entity. Nothing seemed impossible: Its disaggregation, a Protestant republic of the Midi, provinces that proclaimed their independence, others that fell into the hands of the Habsburgs, a fractionation, a satellization, a decadence similar to that of Italy.”

It is at this juncture that Richelieu’s founding idea and policy appear. The political exceptionality of France destroyed by the wars of religion opened the historical horizon to the affirmation of new possibilities of political definition. As Dalmacio Negro writes: “In the founding moments of a political unit – an important classical locus of political philosophy practically abandoned – the situation is in itself exceptional; the decision then being essential. For the political exception is never about something objectively existing and determinable, but has the character of innovation according to a guiding idea. It is a historical decision, about the future; to make a historical possibility viable. In it, other possible options are discarded, in favor of what is chosen and imposed.”

Erlanger exposes it in his own way by raising the historical dimension of the figure of Cardinal Richelieu to the condition of founder of a new political nation after the construction of the first modern State worthy of the name: “Louis XIII wanted to restore greatness and cohesion to this lost kingdom. Relying on this royal wish, Richelieu did much more – he remodeled France, transforming it by a revolution quite similar to those of the twentieth-century, and forced it out of its chrysalis to become a modern nation.”

France was undoubtedly the most advantageous candidate in Europe for the definitive construction of the new political form. Educated by the Church, she also imitated the empire that was reborn with the Frankish dynasty. The new French model took many elements from both one (the Church) and the other (the Empire); and no one better than a French Catholic cardinal, devoted to the service of the Capetian monarchy, to lay the foundations of the new political order that would establish the fortress of the newly inaugurated State, despite many internal enemies and imperial external threats.

“In practice, the action and work of ecclesiastics such as Cisneros, Wolsey, Richelieu or Mazarin were decisive for the consolidation and configuration of statehood. […] All of them under the imprint of the still dominant ecclesiastical way of thinking, which determined general attitudes. The result was that the State, (…), imitated and took from it (the Church) much more than power. For example, the secularized idea of the political body derived from the theological concept of the mystical body in which the ontological individual becomes a social individual; or, the idea of hierarchy and a large-scale bureaucratic administration; and, in the background of all this, as the driving force and justification of its activity, the aforementioned dynamic idea of mission, now applied to temporary security.”

In his biography of the Cardinal, Hilaire Belloc christens Richelieu nothing less than the “founder” of modern Europe: “The consequence of this, finally, and above all, was the creation, in the center of Europe, of a new modern nation, highly organized and subjected to a strong monarchical centralism, which, quickly reaching the heights of creative genius both in literature, as in the arts, as in military science, was to constitute a model that would serve as an example to the new nationalist ideal. This new organized nation was France; and the man who carried out all this was Richelieu. He was the one who, subordinating everything to the monarchy he served (and, therefore, to the nation), had to place everything under the authority of the crown… He was the one who, by work and grace of his own will, managed to consolidate the seventeenth-century, and with it, although involuntarily, the Europe of yesterday. His work is modern Europe.”

It is necessary to interpret the work of the new cardinal-minister (or the minister-cardinal, to be more precise as per his historical performance) in the light of the theoretical battle between the rights of religion and those of politics. This far-reaching battle was fought against the backdrop of the wars of religion that shook the old continent, and only reached a solution after the political success of Richelieu’s work at the head of the State apparatus built by him to serve the people – the French monarchy.

According to Marcel Gauchet, the history of the relations between the political and the religious begins with millennia of religious colonization of politics, that is, millennia of religious “occupation” of a political terrain used to living in a protected minority, by an archaic mentality of a mythical-sacred character. It should not be forgotten that “the political came from the bosom of the sacred,” as Dalmacio Negro reminds us.

With the advent of Christianity, “the religion of the departure from religion,” a new framework of relationships was established, in which the political began to gain its independence. In triumphant modernity, the tables were reversed and we witness, on the contrary, the political colonization of religion (political or secular religions represent perhaps the most advanced stage of this process). Today we perhaps arrive at the philosophical-universalist colonization of the political by the humanitarian ideology of religious democracy and human rights, a new form of secular and antipolitical gospel that claims its privileges with messianic fervor.

Octavio Paz pointed out that politics limits one side with war and the other with philosophy. Philosophy represents, in effect, the limit-form of a universalism that was always the focus of the imperial political form (pagan or Christian). Faced with it, the state-form, with a particularist matrix, is defined by the limit and the frontier of enmity, formulated from political criteria, and tending to progressively eliminate moral or religious residues.

What does Richelieu’s work represent in Gauchet’s transhistoric scheme? In the tension of the double condition present in the figure of Richelieu, minister of a Catholic monarchy who ended up blurring a prince of the Church, the modern transition from the religious pole to the political pole is embodied as an epitome. The significance of this epitome may not be (apparently) distinguished from other cardinals with similar political responsibilities, such as Cisneros or Wolsey – but its decisive relevance in the construction of the ratio-status, which the new hegemonic power of Europe was going to impose, necessarily endows it with a superior role.

Richelieu’s work should be interpreted as a declared exercise of affirmation of the primacy of (State) politics and its friend-foe logic over the demands of the religious script that a pastor of the Church was supposed to attend to. What is striking in this case is that this statement does not occur within the framework of the new relationships generated by the Lutheran thinking with which the predominance of the new State hegemony is frequently associated, but in the context of catholic monarchy, the oldest in Europe.

Richelieu’s new State at the service of Louis XIII asserts itself inwardly against the remains of the feudal aristocracy, against the Levantine high nobility, and above all, against the “State within the State,” represented by the Huguenot minority yet infiltrating the political and social body of the nation. In its determined will to fight abroad against the Austro-Spanish Empire, Richelieu’s State also deploys its energies against the internal enemy, the devout “collaborationist” party that, for essentially religious reasons, presented itself as a French ally of the monarchy of the Habsburgs.

The failed coup against Richelieu, on the famous “Day of the Dupes,” ruined the last hopes of the devout pro-Spanish party. As Etienne Thuau summarized in his study on the reason of State in Richelieu’s time, “in relation to organized society, this authoritarianism translates the will to destroy infra-national solidarity in the same way that it destroys the supranational solidarity of the res publica christiana.”

The strengthening of the new State apparatus required the complete submission to the new order of the old estates, as well as of the dissident Huguenot elite, in significant contrast to the tolerant pastoral care that Richelieu had sustained in his time as Bishop of Luçon. But now the cardinal did not act as a man of the Church, but as the inflexible executor of the policy that would ensure the new greatness of the French monarchy. The success of the minister of Louis XIII is inseparable from the new European order that will follow his death and which can hardly be separated from his work. The Ius Publicum Europaeum enshrined in the Treaty of Westphalia was, at heart, a Ius Publicum Richelaeum.

We noted earlier that the logic of the minister-cardinal’s work was defined by his novel hierarchy of principles in directing the affairs of the kingdom, both internally and externally. Whether against the Huguenots, against the nobility, against the devout party or against the Empire, the line of action of the former bishop was based on the spirit of the primacy of politics, and more specifically, in that maxim of consistent political intelligence, according to Raymond Aron, in turning yesterday’s enemy into today’s ally. The Catholic monarchy of Louis XIII did not hesitate to make a pact with foreign Protestant forces while fighting the Huguenot cancer of La Rochelle. All this in the name of the new reason of State. The Cardinal, according to the portrait drawn by his enemies, carried the breviary in one hand and Machiavelli in the other.

It is worthwhile analyzing the result of this new logic of political purity in international and domestic relations. The new scenario was translated intellectually into an intensification of the secularization of political thought and power. For the political legitimation of a Catholic power as emblematic as the French monarchy, Richelieu’s endeavor required, especially in the context of the wars of religion, an argument from authority that went beyond the strictly theological dimension with which they used to hide many of the conflicts that were presented on the geopolitical arena.

In this sense, Armand du Plessis’s gamble contributed to the purification of a political thought hitherto accustomed to disguising itself in the name of moral and religious causes, counteracting with all the theoretical energy (and with essentially theological ammunition) the growing impact that Machiavelli’s unmasked proposition was beginning to have. At the level of the concert of nations, the politics of France began to find its own moral argument; but it was an argument of political morality that attended to the danger represented by a unipolar Empire which threatened the geopolitical balance of Christendom. Thus, in a line very similar to that which the theorist of Action française, Charles Maurras, later defend in his work, Kiel et Tanger (and which General De Gaulle came to apply strictly in the Fifth Republic), France was rising for the first time as a defender of multipolarity in the international arena. Its place and its mission consisted in being the arbiter or mediator of Christianity to preserve its constitutive balance.

“Faced with Spanish ambition, the most powerful state in the West now had the duty to free Christianity from the threats that weighed against it. Furthermore, the expression of the will of French power did not exclude the desire to restore an international order. Thus, by affirming itself, the national State recognizes other States. For this reason, in the numerous writings that specify or exalt the role of France in Europe, an idea stubbornly persists: That of European balance which will ensure the freedom of the different States.

“However, in the second quarter of the seventeenth-century, a European balance no longer existed. It had been broken by the inordinate ambition of Spain, and it was up to France to assume the mission of putting things back in their state. Statist writers currently claim for the French the glorious titles of “liberators” and “arbiters of Christianity.” This way of speaking was one of the most official. Richelieu himself defined the objectives of French policy in these terms: “…To help restore freedom to its former allies, reestablish peace in Germany and put things back in a just balance because, in the present state, the House of Austria, in no more than six years, when it has nothing more to conquer in Germany, will try to occupy France at our expense.

“In the name of the cause of European emancipation, Richelieu justified his intervention in the affairs of Italy, Germany and the Netherlands. In every military or diplomatic action, it was about liberating a people or a prince from the “oppression of the Spanish,” from the “tyranny of the House of Austria,” from the terror caused by the “insatiable greed” of this House, enemy of the rest of Christianity, and to stop its “usurpations,” to save Italy from its “unjust oppression,” to seek its salvation.”

Although it is paradoxical, this provocative propaganda against the House of Austria did not sublimate the awareness of careful observation of France’s main political enemy, an observation that reached the rank of self-taught education by the method of strategic rivalry. Luis Díez del Corral recalled that “Richelieu admired the organization of the Spanish Monarchy;” although such admiration did not become the pure and simple emulation of its political-administrative structures: “The image of Spain is present in every act, on every page of the Cardinal. Many were the teachings that he received, but not so much to imitate as to replicate, becoming the configurator of a new type of political organization that contrasts with the Austrian Monarchy, and serves to illuminate its historical nature and destiny. The Spanish theme appears especially in the Cardinal’s Political Testament, a work that Carl J. Burkhardt considers Richelieu’s chef d’oeuvre, ‘a compendium of political art, a profoundly French method that will always preserve the value of a model.’”

Indeed, this meticulous observation of the movements of the imperial enemy did not translate into a “mimetic replica” of the structural configuration of the Spanish imperial model, but rather into a replica of an antagonistic State model. This “profoundly French method that will always preserve the value of a model” was, in effect, the result of the war led with an iron hand by Richelieu, who must be considered the founder, not only of Modern Europe (as Belloc pointed out), but also of the state-centered political organization that accompanies it to this day.

As Dalmacio Negro pointed out: “The war was a struggle between the Spanish people and the most perfected State of the time, which has always been the paradigm or prototype of statehood since Richelieu. The Revolution and Napoleon made it the formidable Nation-State to which it owed its superiority.”

The awareness of the superiority of the French model for the war that was being fought also reached those who stood as opposition to it; but the survival of the imperial forma mentis prevented a mimicry in the opposite direction towards the centralization and concentration of power that it implemented. The French crown was marching at a forced pace. The bringing of the Bourbon dynasty into Spain was necessary to initiate, and not without resistance, the slow implementation of the neighboring state- model.

“It is well known that Philip IV rejected the suggestion in this sense of the Count-Duke Olivares, having realized that what Richelieu was doing in France – making it the first great state power, with full awareness of what modern sovereignty means in order to centralize political power. According to Jouvenel, Olivares thought like the Cardinal that the good of the nation and of the State justifies violating any law and privilege, that is, crossing the limits that distinguish the power of the potestas.”

The notion of the French theorist, Bertrand de Jouvenel, on the law of political competition in the narration of “natural history” and of the “growth of power,” offers a very adapted historical-theoretical mold to understand the direct relationship between a war fought by the two Catholic monarchies and the formation, at Richelieu’s initiative, of the new French model of a centralized State.

“These natural jealousies between the powers engendered, on the one hand, a well-known principle, the momentary forgetting of which demands a heavy payment from States – that any territorial increase by one of them, by expanding the base from which it draws its resources, forces the others to seek an analogous increase to restore balance. But there is another way for the State to reinforce itself, which is more fearful for the neighbors than territorial acquisition – the progress of power to exploit the resources that its own territory offers it.”

Jouvenel himself points out Burke’s cutting observation in understanding this same phenomenon as an experience to remember after the French Revolution when, in 1795, he wrote: “The State [in France] is supreme. Everything is subordinate to the production of force. The State is military in its principles, in its maxims, in its spirit, in all its movements … If France had more than half of its current forces, it would still be too strong for most of the States of Europe, as they are constituted today and proceeding as they do.”

Jouvenel draws a general lesson from this dialectic between war and the growth of power: “Any progress of power with respect to society, whether obtained in view of war or for any other purpose, gives it an advantage in war.” Such an equation can alter the order of the factors involved, without diminishing its degree of historical validity; and it is in this second sense that the tendency towards the concentration of power, which this mimetic bid between antagonistic powers has pushed, must be understood.

“Thus, if, on the one hand, every advance of power serves war, then war, on the other hand, serves the advance of power. This dynamic acts as a sheepdog that urges reticent powers to reach the most advancement in this totalitarian process. This intimate link between war and power appears throughout the history of Europe. Every State that has successively exercised political hegemony has sought the means to do so through a more intense pressure on the people than that exerted by the other powers on their respective peoples. And to confront these precursors it grew necessary that the powers of the continent be placed on the same level.”

The author of On Power understood that this process is closely linked to the French resistance to the Spanish Empire, as happened in England: “The development of absolute monarchy, both in England and in France, is linked to the efforts of both dynasties to resist the Spanish threat. James I will owe his great powers to the army. If Richelieu and Mazarin were able to elevate the rights of the State so much, it was because they could continually invoke external danger.”

The testimony of Fontenay-Mareuil (1594-1665), who was a diplomat and military man in Richelieu’s time, is especially relevant, in Jouvenel’s opinion, to give us “an idea of how military urgency contributed to liquidating the old forms of government and cleared the way to absolute monarchy.” In the words of the French ambassador: “It was really necessary to save the kingdom…that the king had sufficiently absolute authority to do everything that pleased him, since he had to deal with the king of Spain, who has so many countries to obtain everything he needs. It is clear that if he had had to gather the Estates General, as is done in other places, or depend on the good will of parliament to obtain everything that he needed, he would never have been able to do anything.”

The increase in number of the French military under Richelieu’s command is quite a telling indicator of the transformation carried out in France as a result of the political and armed confrontation with the Habsburg Empire: “Richelieu, who found that all the forces in France had been reduced by Marie de Medici to 10,000 men, raised them to 60,000. Then, after having fought the war in Germany for a long time, and ‘reaching for the purse rather than the sword,’ he raised an army of 135,000 infantry and 25,000 cavalry – forces that France had not seen in eight centuries.”

There is nothing better than the testimony of Richelieu himself to understand this exorbitant growth of the resources made available to the new State machinery. The cardinal justified it all by the “incessant purpose of stopping the advance of Spain.” The war, midwife to absolute monarchy, not only buried the old aristocracies in this way (confirming Vilfredo Pareto’s assertion about the circulation of the elites) but also prepared for the funeral of the Spanish imperial form, without whose threat there would be no emergence of the gigantic apparatus that, brought about by force of circumstances for the defense of the French nation, was already creating the path to that autonomous body eager to exploit it, as suggested by the scholio of Gómez Dávila.

III. Machiavelli, The Afrancesado

In France, the success of this new national model in competition with the Empire could not fail to be understood outside of the historical demands of an adaptation of the discourse to the particular relationships that, within the framework of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, were imposed between the religion and politics. In this doctrinal and theoretical corset, political knowledge struggled to reach the full margin of autonomy possible, in order to meet the demands of a confrontation between opposing Catholic powers.

In this cultural context, it was evident that France had everything to lose against an imperial power as universalist in its aspirations as the Church itself, and for the same reason, more theoretically legitimized to impose its rights to political hegemony before the doctrinal court which protected the ideas and mentalities of a time in need of theological justification. In this sense, Richelieu’s commitment to the propaganda of the ideas of the so-called “State Catholics” should also be considered as one of the successes of his work of directing the political affairs of the French crown.

An intellectual battle was raging, paralleling the political and military battle; and the critical reception in the Catholic world of Machiavelli’s work was central to the controversy. In France, given the nation’s needs for its defensive geopolitical position in the face of the supremacy of the imperial order, there was an urgent need for a split between Christian ethics and morals and the demands derived from the exercise of political power that had now begun to be assumed.

Meanwhile in Spain, there was no room for assimilating a Machiavellian discourse which was directly opposed to the national legitimizing talismans since the Reconquista (however, Tacitism has been judged as a form of “crypto-Machiavellianism,” very widespread in Catholic countries): “The work of Machiavelli, with its political and historical critique of Christian morality and the papacy, could not compete in a Spain in which the State made Catholicism more and more its basilar foundation and which placed the mythical principle in the refuge of Covadonga of its state-construction and imperial expansion.”

Undoubtedly, this frustrated assimilation by the Spanish elites of the new political discourse of propaganda deserves attention which, at the service of the French monarchy, increasingly vindicated the legitimate autonomy of the reason of State within the framework of Catholic thought, all the while denouncing as spurious the theological arguments with which the Spaniards tried to disguise, according to this interpretation, a political and military hegemony that exclusively served their own interests.

“Already in 1623, la France mourante showed what danger the policy of the King of Spain posed for France: ‘…If we allow his conquests to be strengthened, it is very certain that he will become master of all Italy, and dominator of the Germanies, and by this means he will encircle this crown everywhere by powers so great that it will be impossible for to resist it…’ The Discours sur plusieurs points importants (1626) denounces ‘…those who have always aspired to the Empire of the Universe.’ La Lettre déchiffrée (1627) attacks Spanish politics that wants to ‘…raise the affairs of heaven to the level of those of Madrid,’ and for whom ‘everything that is done by the Vatican is criminal if it is not ratified in the Escorial.’ In 1626, the preface of Pierre de touche politique specifies the inspiration for the book: ‘…it uncovers the purpose that the Spanish have to oppress all their neighbors under the pretext of Religion and Charity, and to establish by that means their Universal Monarchy, and shows that this nation has always had the interest of God and the Church on its lips, and it has never had it in its heart.’ After the accusation of imperialism, the reproach most frequently leveled at the Spanish is that of using the spiritual for temporal purposes.”

This new anti-imperialist argumentative arsenal was not manufactured in a completely spontaneous way. It was driven by the theoretical ammunition of Cardinal Richelieu himself, who did not hesitate to point out the political servitudes of the “Spanish theology” of the time.

“Richelieu, in his Memoirs, denounces the Spanish pretexts. Foreign policy pamphlets did not stop attacking the ‘new theology’ manufactured by Spain to cover its ambitions… It is therefore well established in the political creed of the ‘good French:’ When the Spanish defend Christianity, we can be sure that it is Christianity that defends the Spanish.”

In the combat between the Empire and the new state-form of the French model, a struggle was also taking place in the field of political thought. In particular, this theoretical controversy took place within the religious framework of Catholic legitimacy, in which France seemed to count, by her birthright as eldest daughter of the Church, with credentials that could compete with those of the Holy Empire.

Despite the undoubted superiority of the state-form to respond to the demands and challenges of the confrontation that was drawn on the geopolitical board, Spain could not assume those new usages that clashed, head-on, both with its own legal and political traditions and with its political history of national reconstruction (the Reconquista), and so attached to a legitimizing religious discourse that there was no room in it for the slightest split for the reason of State independent of the guardianship of the faith.

On the other hand, this national character and this historical-political-religious personality seemed to fit much better with the imperial narrative, especially at a time marked by a Protestant Reformation that reinforced the rights of justification of religious orthodoxy to impose the universal order of the sword of Rome. These roots explain, to a large extent, the costly assimilation of the state-model in Hispanic lands.

“As for Spanish political thought, it was forced, in Abellán’s words, to have to live ‘in fact’ under a political form, ‘the State,’ in which, however, ‘it did not theoretically believe.’ And perhaps it is true that the Spanish authors did not believe much in the ‘modern State;’ not so much because religion prevented it, but rather because they believed in something that was not exactly the modern State: A Catholic Empire.”

Unlike Spain, France had all the reasons in the world to believe in the political form of the State; and if reasons were lacking, there was no hesitation in inventing them as much as necessary. The autonomy of the demands of politics from the imperatives of religion was undoubtedly the central philosophy of the new propaganda of the French monarchy and the core from which all these reasons emerged. And it was Richelieu himself who fully advanced it, by asserting, in a famous phrase and with all the religious authority of which a prince of the Church was capable, that the interests of the State are different from the interests of the salvation of the souls.

“Placed between its Protestant allies and Catholic Spain, Richelieu’s France faced a difficult choice. State or religion. Such was the dilemma that arose in the conscience of many French people and the writings of the time attest to their discomfort… In another respect, Richelieu did not say otherwise and, in the instructions to Schomberg often cited, we read: ‘”Different are the interests of the State, which bind the princes, and different the interests of the salvation of our souls”.’”

The link between this new secularization of political thought and the state- political form is of interest in this regard. In addition to the interest that this commitment to a political realism freed from religious ties supposed for theoretical propaganda in the service of the Cardinal, there is an undoubted favorable propensity of the state-scheme towards the intellectual figures of the most secular political thought. These figures found it difficult to break through the legitimacy structure of the imperial form, too impregnated by the weight of the sacred (the “Holy” Empire) and by the will to impose a cosmocracy of universalist ambitions that, in the manner of Campanella, it necessarily contaminated or dissolved the political dualities of the conflict in its purest sense (friend-foe).

IV. Political Creation Outside The Polis

Sheldon Wolin has analyzed the creative facet inherent in political thought and its recurrent disruptive contribution, between the lines of continuity of the inherited Western tradition, as well as the relationship of these creative leaps with the historical transformations of political forms. For Wolin, originally, political thought was related to the characteristic problems of the polis, that is, to its size, problems and intensity, features that offered a general framework marked by a very defining effervescence of a way of living and living together in public space.

This simple intuition immediately translated into another question. If political thought is a thought related to the problems of the polis, can that same model of thought survive in the contexts related to other political forms? In other words, how does an alien spatial configuration affect the spatial limits, concerns, and conflict intensity of the polis in political thought?

The contrast between the “nervous intensity” of Greek political thought, attached to the dimensions and effervescence of the polis, and other human sensibilities, characteristic of a different spatial conception, was raised for the first time in relation to the “the mood of later Stoicism which leisurely, and without the sense of compelling urgency, contemplated political life as it was acted out amidst a setting as spacious as the universe itself.” This first contrast already heralded the decisive influence that this new universalist spatial sensibility, defining the imperial form, was to imprint on the configuration of political thought, impoverishing and blurring its essential categories.

“…Yet the central fact from the death of Alexander (323) to the final absorption of the Mediterranean world into the Roman Empire was that political conditions no longer corresponded to the traditional categories of political thought. The Greek vocabulary might subsume the tiny polis and the sprawling leagues of cities under the single word koinon, yet there could be no blinking the fact that the city denoted an intensely political association while the leagues, monarchies, and empires that followed upon the decline of the polis were essentially apolitical organizations. Hence if the historical task of Greek political theory had been to discover and to define the nature of political life, it devolved upon Hellenistic and later Roman thought to rediscover what meaning the political dimension of existence might have in an age of empire.”

The way to overcome the difficulties associated with the new social representation of space (the enormous distances that were now imposed in the face of the customary relationship of citizen proximity that defined the Greek political atmosphere) consisted in a recovery of the sacred symbolism, which was then thereafter to merge with the discourse of legitimacy of the imperial forms.

“Where loyalty had earlier come from a sense of common involvement, it was now to be centered in a common reverence for power personified. The person of the ruler served as the terminus of loyalties, the common center linking the scattered parts of the empire. This was accomplished by transforming monarchy into a cult and surrounding it with an elaborate system of signs, symbols, and worship. These developments suggest an existing need to bring authority and subject closer by suffusing the relationship with a religious warmth. In this connection, the use of symbolism was particularly important, because it showed how valuable symbols can be in bridging vast distances. They serve to evoke the presence of authority despite the physical reality being far removed.”

The impact of this new configuration of the dimensions of the relationship of the men subjected to the new imperial power not only ruined the classical categories of citizenship of Greek thought but also altered the moral and concrete structure (that so characteristic symbiosis of ethics and practical sense) of a perception of the political, marked by a closeness to the real problems of public space and a direct experience of its associated conflicts.

Faced with this hyperesthesia of Greek political realism, an increasingly abstract conception of political life was now rising, which required, to the same extent, the help of a theoretical and symbolic apparatus, twinned with the morphology of a community, without defined contours, and that overflowed the limits and borders of vivid representations, in order to enter the infinite space opened by universal concepts and categories.

“With the development of imperial organization, the locus of power and decision had grown far removed from the lives of the vast majority. There seemed to be little connection between the milieu surrounding political decisions and the tiny circle of the individual’s experience. Politics, in other words, was being conducted in a way incomprehensible to the categories of ordinary thought and experience. The ‘visual politics’ of an earlier age, when men could see and feel the forms of public action and make meaningful comparisons with their own experience, was giving way to “abstract politics,” politics from a distance, where men were informed about public actions which bore little or no resemblance to the economy of the household or the affairs of the market-place. In these circumstances, political symbols were essential reminders of the existence of authority.”

The new cosmic sensitivity, initiated by Stoic cosmopolitanism and which adapted so well to the ethos of imperial power (personifying itself even in egregious figures such as Marcus Aurelius), was called to be united, if not to merge, with soteriological ambitions of a religious nature, especially when, in time, the Empire form was to proclaim Christianity as the official religion: “Another and far stronger impulse, but one that was equally apolitical, was to suffuse power with religious symbols and imagery…This was a certain sign that men had come to look towards the political regime for something over and above their material and intellectual needs, something akin to salvation.”

From then on, and despite the theological reservations of a Saint Augustine in relation to Varro’s political theology, the historical-political moment was in the best position to correlate religious and political categories to the point of fostering a politics legitimized by theology and a theology endorsed by existing political forms: “This belief in a political savior, as well as the persistent attempts to assimilate the ruler to a deity and to describe the government of human society as analogous to God’s rule over the cosmos, were themes reflective of the degree to which political and religious elements had become deeply intermixed in men’s minds. In a variety of ways, in the conception of the ruler, subject, and society, the “political” quality was becoming indiscernible. At the same time, from the fourth century B.C. until well into the Christian era, men repeatedly thought of the Deity in largely political terms. Thus the paradoxical situation developed wherein the nature of God’s rule was interpreted through political categories and the human ruler through religious ones; monarchy became a justification for monotheism and monotheism for monarchy.”

It is not necessary to appeal excessively to the imagination to understand that this new mentality contributed unexpectedly but decisively to progressively blur the purity of political concepts that had grown in the heat of the conflictive intensity of Greek city life. The political categories that had populated the minds of the leading Greek philosophers were not born out of abstract speculation but out of civic life that, significantly, many of them had experienced in their own lives.

In this way, the advent of the imperial era washed away, if not the ruin of the political categories inherited from Greek philosophy, then at least the experience inherent in the Greek logos mode of political thought, thus generating a collective temperament far removed from it and increasingly apolitical ways of thinking: “In looking back on the kinds of political speculation that had followed the death of Aristotle, it is evident that the apolitical character of life had been faithfully portrayed, but no truly political philosophy had appeared. What had passed for political thought had often been radically apolitical; the meaning of political existence had been sought out only in order that men might more easily escape from it.”

Inevitably, from that very moment, through the infection of sacred symbolism in imperial forms, a path was already opening for the penetration of moral Manichaeisms that were to progressively overlap with the defining dualities of the essence of what political, as studied, for example, by Julien Freund, especially the friend-foe duality for foreign relations and the command-obedience duality for internal ones.

The political world, for this new moralism, was from now on divided into “good” and “bad” (that is, faithful and unfaithful, orthodox and heretics), thus breaking the spatial and theoretical delimitation between the political and the ethical, built by the realism of authors like Thucydides.

From now on, there was no longer a “political” morality (that is, a morality adapted to the demands of political reality), but rather the political (everything political, with its theoretical and practical arsenal) was subjected to “the” moral, a unique and universalist morality called to be colonized, over time, by a faith (the Christian one) that, unlike the other two monotheisms (the Jewish that preceded it, and the Muslim that succeeded it), paradoxically, never harbored any political ambition: “Instead of redefining the new societies in political terms, political philosophy turned into a species of moral philosophy, addressing itself not to this or that city, but to all mankind… Seneca’s suicide was the dramatic symbol of the bankruptcy of a tradition of political philosophy that had exchanged its political element for a vapid moralism.”

From this new scenario, which ultimately prevailed, we can gather striking precedents that, as symbolic advancements, were presented in the unprecedented Alexandrian imperial experiment. Eratosthenes incarnates, avant la lettre, before history the figure of an anti-Schmittian advisor, who conquers for morality the territory hitherto untouched by politics: “When Eratosthenes advised Alexander to ignore Aristotle’s distinction between Greeks and barbarians and to govern instead by dividing men into ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ this marked not only a step towards a conception of racial equality, but a stage in the decline of political philosophy… Eratosthenes’ advice indicated that political thought, like the polis itself, had been superseded by something broader, vaguer, and less political. The ‘moral’ had overridden the ‘political,’ because the moral and the “good” had come to be defined in relation to what transcended a determinate society existing in time and space.”

In conclusion, the historical decline of the polis, understood as a spatial relationship adapted from the human to the political, dragged political thought, originated by the polis, towards an intellectual, religious and moral habitat less adapted for its intellectual survival.

In this environment, which was that of Empire first and feudalism later, political philosophy languished. Although it preserved its theoretical validity in a mausoleum, in which the echo of a vocabulary born from a claustrophobic microcosm of internal rivalries was frozen over the centuries, it awaited its resurrection, by awaiting an ideal environment for palingenesis: “The decline of the polis as the nuclear center of human existence had apparently deprived political thought of its basic unit of analysis, one that it was unable to replace. Without the polis, political philosophy had been reduced to the status of a subject-matter in search of a relevant context.”

The relevant context for the regeneration of political thought appeared in a universe that was partly reminiscent of that of the ancient Greek polis. The turbulent air that was breathed into the Italian republics of the Renaissance oxygenated minds capable of restoring a fuller understanding of new (and old) political realities, presenting themselves again under a new day. Machiavelli was the theoretical epitome of the modern political firmament, but the atmosphere explains the phenomenon. “Almost a century before The Prince was written, a viable tradition of “realism” had developed in Italian political thought,” states Wolin.

However, this new sensitivity to political issues would take time to break through and achieve definitive recognition, for the inertia of the old world continued to weigh on it with the tradition of political-religious symbiosis. It is not surprising that the political butterfly did not finally emerge from the chrysalis until these new categories were assumed precisely in the religious habitat that conditioned it.

The nascent national monarchies offered an incomparable setting for the testing of this new offer of understanding of the political fact. In monarchies headed by statesmen who were at the same time princes of the Church, as in Richelieu’s France, the obstacle of theological legitimation could be overcome with greater ease. In the geopolitical context of religious wars, whose moral demands could hardly be reconciled with the incipient reason of State, the fusion of the political with the religious, far from being an obstacle to the autonomy of the former, was presented as its only (and best) platform for its launching.

The following reflection by Wolin, much broader in scope and intent, nevertheless, allows an interpretation in a French way that offers a powerful framework of analysis to understand the progressive secularization of political thought in France ruled with an iron fist by the “man in red.”

“The growing merger of political and religious categories of thought was an intellectual footnote to the spread of political control over national churches. When these tendencies were joined to the growing strength of the national monarchies and to an emerging national consciousness, the combined effect was to pose a possibility which had not been seriously entertained in the West for almost a thousand years: an autonomous political order which acknowledged no superior and, while accepting the universal validity of Christian norms, was adamant in insisting that their interpretation was a national matter. But while Reformation Europe could accept the practice of an autonomous political order and disagree primarily over who should control it, there was greater reluctance to explore the notion of an autonomous political theory. As long as political theory contained a stubbornly moral element and as long as men identified the ultimate categorical imperatives with the Christian teaching, political thought would resist being divested of religious imagery and religious values.”

There is no doubt that the new political and religious scene had little to do with that of the Greek polis in which men such as Plato, Aristotle or Thucydides had been born and lived. Almost two millennia had passed and the men of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-centuries lived immersed in the dogmas of a faith unknown to the ancient Greeks.

However, far from what might seem at first glance to be the spirit of secularism that genuinely characterized the letter (and spirit) of the believers in Jesus Christ, there yet awaited a favorable context for the definitive conquest of a political autonomy that did not contradict, said its postulates, as seriously as in the case of those who followed the law of Moses or Muhammad.

Furthermore, as Jerónimo Molina notes, the anthropological pessimism of the political conception of a Machiavelli was an unwitting debtor of Christian theology; and, although the echoes of the creator of The Prince seem to resonate in the history of the Peloponnesian war, the profundity of the intellectual equipment on the condition of man, which distinguished the Florentine, as a result of more than 1500 years of Christian tradition, was not within the reach of a military man like Thucydides.

“This pessimistic strain, which grew out of the realization that the new knowledge must be conversant with evil and that its major concern was to avoid hell, confirms that it was a post-Christian science rather than one inspired directly by classical models. The assertion that ‘all men are wicked and that they will always give vent to the malignity that is in their minds when opportunity offers’ was one which Greek political science never entertained and Christian doctrine never doubted.”

V. Laicization And The “Catholic” Reason Of State

In this context of French opposition to an imperial power that based its political legitimacy on an authority that appealed to arguments of a religious nature, the autonomy of the political did not appear as the result of an independent intellectual construction, but rather from the demands of a propaganda at the service of military and political action determined by an atmosphere of religious hegemony in the field of argumentation about temporary realities.

“Discovered or rediscovered by the statists of Richelieu’s time, the idea of the autonomy of politics does not come from pure speculation, but from a whole series of concrete conflicts: The dispute over Gallicanism, the problem of relations with the Protestants, and above all the Franco-Spanish conflict. The principle of the independence of politics was the anti-Spanish weapon par excellence.”

All of this explains why the course of the debate led to probably unforeseen conclusions. This is proved by the fact that the cardinalist propaganda accepted the challenge of the religious foundation of the theoretical reasons to present in the face of Spanish demands. Spain had chosen a bad enemy to uphold the sacred superiority of her cause. The first-born daughter of the Church would not hesitate to connect with the foundations of a divine mission so frequently highlighted by the Petrine See: “The religion of the monarchy could not but confirm the French in the idea that their country had a mission and that it continued the tradition of the Gesta Dei per Francos so well expressed by the words of Joan of Arc: ‘Those who make war on the Holy Kingdom of France, wage war on King Jesus.’”

Nevertheless, the religious dialectic used in the conflict did not cease to be, for the political interests of the French monarchy, a defensive weapon designed specifically to counter the offensive of the Habsburgs, no matter how few actually used it with full conviction. Little by little, strictly political arguments came to the fore, while religious rhetoric was progressively located in the space of stage decoration. After all, the confrontation of the two greatest Catholic powers of the time was not the most appropriate terrain for a resolution of the conflict on a religious basis. As it is a markedly political struggle, it was inevitable that the political arguments would gradually come to occupy the space with the greatest protagonism.

The Catholic State was not just a name of one of those government pamphlets serving Richelieu’s policy. The name chosen for that publication indicates the general inspiration for its content. Undoubtedly, this periodical, which appeared at the beginning of Richelieu’s ministry in 1624, was distinguished by its doctrinal vigor, in its defense of the cardinal’s new policy. The exact title was Le Catholique d’État ou discours politique des alliances du roi très chrétien contre les calomnies de son État. As the scholars of the press of the time pointed out, this pamphlet constituted the hardcore of propaganda in the service of the minister of Louis XIII.

The cardinalist pamphleteer revolted against the intellectual and moral contempt that at the time was directed at the association of the figure of the “Catholic” and the idea of “State policy.” In this way, it placed with pride in its very title the spirit of this association, elevating it to the rank of national and religious communion and apologizing to those who, like the sovereigns of France, knew how to combine the interests of the State and the Catholic Church. However, in the end (and beyond the immediate intentions of its promoters), the thrust of its doctrinal argumentation contributed to progressively dissociate the foundation of the political order from any religious horizon, reworking the foundations of a matched political realism to the interested analysis of the French position in the conflict against the Spanish Empire.

“The paradox of the Catholique d’État resides in the fact that after having founded absolutism on an authoritarian conception of religion, it came to separate politics from religion. It does not approximate the power of God except to better ensure its independence… Rejecting the religious arguments of Spanish propaganda and underlining the separation of politics and morals, the Catholique d’État placed the conflict between France and Spain in its true light – that of the confrontation of two national interests.”

As a consequence of this growing translation – from the space of religious definition to the field of political definition – the terminology of the cardinalist writing progressively colors the friend-foe duality of the political opposition with national and non-religious characters, thus affirming a delimitation of intellectual conflict in terms ever closer to the real meaning of political confrontation: “While foreign pamphlets separated men into Christian and ungodly, the Catholique d’État took a different view… Thus, in the cardinalist writing, the friend-foe distinction, capital in political thought, was based from now, not on religion, but on nationality and patriotism.”

Thus, from the study of propaganda publications, such as, the Catholique d’État, it is possible to analyze the general meaning of a process of gradual doctrinal decantation. Although the opposition against the Catholic Empire forced a response in the theological field (or more exactly, in the theological-political field), the prolongation of the conflict imposed, in addition to the refutation of the foe’s religious “pretexts” with the same Catholic ammunition that it used, a necessary transfer of the epicenter of the intellectual confrontation towards a political territory, not sown by the theological-moral seed. Without this historical circumstance (fundamentally political and military, as well as religious) that surrounded the cardinalist publication, the “para-doxa” of the Catholique d’État cannot be understood.

“Not without its literary qualities, the Catholique d’État contains, in abbreviated form, the theory of the authoritarian State of the reign of Louis XIII, and defines the ideal of a ‘political Catholic,’ of the ‘good patriot.’ Its paradox consists of starting from a religious conception of power in order to separate politics from religion; or, more exactly, from a religion understood in the Spanish way… By developing a new conception of politics, there is a sense of that laicization of power that became the dominant feature of Richelieu’s time.”

The new climate brought about by the Franco-imperial conflict was to propitiate a state of mind tending to consider with suspicion the religious pretexts adduced by a Spanish-Austrian foe maliciously inclined, in the eyes of cardinalist propaganda, to locate the theoretical epicenter of the confrontation in the doctrinal space most adapted to its own benefit. This suspicion unconsciously contributed to disavowing the religious legitimation of political causes, presenting it as a veil, self-interestedly used by a hand determined to hide the true face of its owner.

The similar arrangement of the pieces on the board between the two contenders (Catholic powers competing in moral authority in an atmosphere of religious hyper-legitimacy) originated the unexpected transformation of the rules of the game, until then in force, and with it the consequent secularization of the political thought. It can be said that the Spanish imperial hegemony gave rise to a reason (Catholic and French) of State.

“The consequence of this process to Spain and its supporters was, without a doubt, to make religious justifications in politics suspect. Here is a curious detail of the history of political thought in the seventeenth-century: The idea that religion is a deception of the rulers and a secret of domination has been spread by publicists of the very Christian king writing against the pamphleteers of the very Catholic king. The conception that makes religion an imposture of the powerful has been, if not produced, at least reinforced by the confrontation of great nation states. Thus making religion suspect, what could remain as the law of international relations but the interest of each State and natural law? And indeed, if one looks for the basis that the statist writers give to Richelieu’s policy, it is found that they increasingly invoke the national interest and the reason of State. They certainly do not make the kingdom of France a secular state, but they are led to separate more clearly than their predecessors and their opponents the interests of the State from those of religion. The fact that Spain and its supporters insisted on the union of faith and politics undoubtedly contributed much to this secularization… If they still mixed religious arguments and rational arguments, the predominance of the latter is noticeable.”

“Thus,” Etienne Thuau writes, “reason of State prepared to become the main argument of Richelieu’s policy.” This “politics of sleeplessness,” a peculiar form of French-style Machiavellianism in a national-Catholic guise, must be understood as the necessary reaction to a given context. The uncomfortable truth of a political realism, purged of moral mystifications and theological disguises, could not break through without attending to that context.

“It seems that in Richelieu’s time pro-Spanish publicists and French pamphleteers opted for a veiled politics to that of wakefulness… Thus, in the eyes of many seventeenth-century Frenchmen, Gallic ‘naivety’ was opposed to Spanish hypocrisy. This naivety consisted, at the outset, in revealing to a limited public the levers of power and in taking the layman behind the scenes of government. More profoundly, it tended to desecrate power and detach it from the moral and religious justifications with which it was often illegitimately cloaked. It is not always pleasant to speak the truth, and it is to his lucidity that Richelieu owes, as with Machiavelli, his bad reputation.”

The reference to Machiavelli is not without meaning and perhaps helps to place the doctrinal debate, limited by the circumstances of Richelieu’s time, in a broader context. The “French” reason of State does not arise from the intellectual import of the “letter” of the Florentine’s thought, but rather from the adaptation of its “spirit” to the concrete historical plane of a conflict marked by very precise connotations. And, fundamentally, because of the remarkable personality and ambition of a figure of the stature of Richelieu.

“The enigmatic Richelieu in fact embodied for his contemporaries the type of politician marked by Machiavellianism… Faithful, if not to the letter, at least to the spirit of Machiavelli’s doctrine, they made political thought progress since, thanks to them, under the Richelieu regime, the Machiavellian current came to merge with that of the Reason of State.”

The peculiar religious circumstances of the conflict between the French monarchy and the Habsburg Empire help to understand the emergence of this “Catholic” Machiavellianism in Gallic lands and the scope of the contradictions that it carried within it. Another factor that should not be forgotten, when interpreting the period and the historical precipitate (essentially involuntary) that happened to it, is the existential personification of these contradictions. By this we mean that the undoubted political motivations of its main architects were not combined with their religious responsibilities at the cost of a tribute to cynicism or hypocrisy, as a certain distorted and caricatured exhibition tried to underline later, especially in field of literature (The main responsibility, in this regard, is that of Alexander Dumas and his three musketeers).

The genuine religious spirit of men like Richelieu and Father José, the most intimate collaborator of the cardinal’s politics, but also a Capuchin steeped in a fervent missionary ideal, should not be underestimated with chronocentric criteria, if one does not want to blur the real significance of the events of the time (The most representative work on the historical significance of the figure of Father José and his contribution to Richelieu’s political career remains that of Aldous Huxley, Gray Eminence). The sincerity with which these ministers and religious lived their own internal conflicts genuinely fed the sense of politics and the thinking of the main protagonists of the moment, leaving a legacy that would decisively influence the future of a new Europe.

“Richelieu may not have had his breviary and Machiavelli at his table, but his Machiavellianism was as indisputable as his faith. Father José dreamt of the Crusade at the same time that he worked for the ruin of the very Catholic Monarchy… The thought of the statists, like that of the men of the seventeenth-century, united the contradictions. They glorified the prince, vice-king of God, responsible before his Creator and, at the same time, invoked the irresponsibility of the reason of State… In good logic, the opposing ways of thinking in life are summoned and completed. Inconsistencies also have their logic… What seems to us incoherence is, to a certain extent, the very mark of life. Those seemingly incompatible principles that coexist are actually the past and the present facing each other.”

Although the sense of criticism of figures like Richelieu usually insists on the amoral character of their political endeavors and on the religious instrumentalization of their power interests, the truth is that many of the men who collaborated with those endeavors were also moved by a sincere desire for religious purification. The delimitation of the respective fields of politics and religion should not only serve to liberate politics from religious servitude but also, and for the same reason, to emancipate religion from bastard political ties.

“Closer to reality, the statism of Richelieu’s time, assuming violence to overcome it, tried to agree on force and reason. Attempting to reconcile violence and reason, flirting with Machiavellianism to overcome it, statism propagated a new conception of the relationship of men with each other and of man with God. By secularizing political thought, Richelieu developed natural law and a new theology. Statists reject in the first place any religion that mixes God too much with human affairs and that is preached by people ‘more political and carnal than spiritual.’ as Theveneau put it. They judge very suspiciously political-religious endeavors in the Spanish fashion, such as the League, the Evangelization of the Indies, the holy war against the heretics or the infidel. They aspire to a purer, more interior religion, oblivious of material interests and the narrowness of dogma.”

The characteristic realism of this “Catholic Machiavellianism” could thus enlist the support of sincerely religious men, without whom the contemporaneity of its emergence could hardly be assimilated with the appearance of eminently spiritual figures such as Pascal (1623-1662), and his decisive and parallel contribution to both scientific and religious thought.

“Reason, for the seventeenth-century, is therefore, to a certain extent, daughter of the State of Richelieu,” as Etienne Thuau pointed out, and continued: “The brutality of the time of Louis XIII made political apriorisms impossible… But this oppressive thought is also an instrument of liberation. In its positive aspect, the statist works of our period contribute to secularize the State and the League of Nations, and the most remarkable fact of this influence is that the progress of rationalism is parallel to that of the State.” The environmental secularization of the spirit of the time undoubtedly purified the political analysis but also engendered a new moral and religious sensibility, announcing, on the other hand, the new ideological and cultural winds of the great revolutionary rupture of the late eighteenth-century.

“This Christian statism placed ample confidence in the human will to build civil society. It is based on ancient and modern rationalisms and gave great autonomy to the State… It is the same with the political polemics of Spain, as with Pascal’s polemics with the Jesuits: They did a lot to secularize thought and expand the morals and politics of honest men. Equally distant from Spanishized theology and from Machiavelli’s atheism, the politics of honest men – or, more precisely, that of the bourgeoisie, men of law and civil servants – tends to be based on natural law, a Christian rationalism and, very often, deism.”

To relate the links of this great (and indeed foundational) “French Machiavellian moment” with the revolutionary hecatomb, which will take place a century and a half after the death of Richelieu, constitutes the task of a work that goes beyond the limits of this one. Instead, we will content ourselves with pointing out, by way of a conclusive synthesis, that the Catholic reason of State that stands as the main novelty of French political thought at the time of Louis XIII, which in his reign “allowed the great Cardinal to fulfill his incomparable foundational and restorative dictatorship,” is a paradigmatic example of that creative factor that accompanies the history of Western thought – in that permanent tension between continuity and innovation, analyzed by Sheldon Wolin, as we have highlighted throughout this brief study as hermeneutical support of our interpretation. This creative factor is undoubtedly linked to that imaginative dimension inherent in political thought, as highlighted by the American author, but also to the socio-historical circumstances that incardinate the imaginative leaps of the philosopher.

“The varied conceptions of space indicate that each theorist has viewed the problem from a different perspective, a particular angle of vision. This suggests that political philosophy constitutes a form of ‘seeing’ political phenomena and that the way in which the phenomena will be visualized depends in large measure on where the viewer ‘stands.’”

In other words:

“The concepts and categories of a political philosophy may be likened to a net that is cast out to capture political phenomena, which are then drawn in and sorted in a way that seems meaningful and relevant to the particular thinker. But in the whole procedure, he has selected a particular net and he has cast it in a chosen place.”

Although Richelieu’s time did not have the support of a political philosophy similar to that of an observer of the English Civil War such as Thomas Hobbes, it nevertheless developed an analogous propaganda apparatus for self-defense, mutatis mutandis, which we have met in the twentieth-century. The interests of the cardinalist press constituted that socio-historical context to which Wolin refers, and which no longer represented so much the perspective adopted by the “observer” (who is associated with an impartial and almost scientific agent), but the approach taken by whoever he observed and at the same time influenced events, in a position similar to that which defined the trajectory of the diplomatic Machiavelli. “The political philosophy of the Richelieu regime is therefore less the fruit of disinterested reflection than of the mask of the will of the State and an instrument of domination. The impression of incompleteness that his works offer comes from his practical aspirations,” Thuau also pointed out.

It is no coincidence that this scholar of reason of State during Richelieu’s time emphasized that “thanks to creative distortions and respectful falsifications, jurists, theologians and men of letters worked for ‘statist crystallization.’” The reference to the creative factor and the fundamentally proactive position of its new interpreters (observers and actors at the same time) clearly delimits the peculiar socio-historical dimension of the imaginative character that we can attribute to the political thought that germinated to the beat of the cardinal’s work. The fusion of the jurist, theologian and man of letters came to be represented, with a similar political role, by the twentieth-century intellectual.

The echoes of this desacralization sponsored by the propaganda demands of the French throne defended by Richelieu were felt, over time, beyond the space-time coordinates of the Spanish-French conflict that saw it born, attacking the descendants of Louis XIII with arguments similar to those used by cardinalist advertising. Only two centuries later, the argument for the desacralization of politics that favored the geopolitical interests of the kingdom of France ended up ruining its own internal foundations.

However, the antecedents that culminated in the French Revolution had, in the meantime, become contaminated with the infection of a new secular matrix moralism, an enlightened humanitarianism that undoubtedly inherited the transcendent desacralization of power that was initiated involuntarily at the initiative of the propagandized, in the service of the Cardinal, but which reoriented the religious potential of the French tradition towards intramundane purposes. Hence, we must ask ourselves about the weak intellectual offspring of the crude political realism that emerged as a result of the claims of affirmation of the French monarchy of Louis XIII.

“One feature of the cardinalist propaganda deserves to be noted: Its tendency to offer a brutal vision of reality… The cardinalist press therefore tended to present political life as a confrontation of forces, a harsh view that seemed to “free spirits” a sign of truth. This feature of Richelieu’s time is striking when his accomplishments are compared with those of a later time.”

Perhaps the French theory of reason of State that emerged in Richelieu’s time died as a consequence of its success. French absolutism was to dominate European geopolitics from the treaty of Westphalia. The requirements of his policy, from then on, were to be different from those under the command of the man in red. If Richeulian Machiavellianism is to be fairly considered as one of the golden ages of political realism, its profound nature is better understood if it is seen, in the pre-Westphalian European context, as a brief parenthesis between theological moralism that it preceded and the immanentist secular moralism that buried it.

“We can indeed wonder if the time of Richelieu, who made Machiavellianism flourish, was not the moment of truth of the century. Indeed, the seventeenth-century, a century of violence, seems to have been a “Belle époque” for political realism… The Middle Ages lived in a world that was made bearable by the presence of God. The Age of Enlightenment, without ignoring the miseries of the human condition, nurtured a humanitarian ideal. Our gloomy period only looks at the gross facts without any ray of light coming to illuminate them.”

This is the paradox that perhaps summarizes the history of the vision of the political, which is also the history of its visionaries: That all light outside their domain is not a light that illuminates but a light that blinds.

Domingo González Hernández holds a PhD in political philosophy from the Complutense University of Madrid. He is a professor at the University of Murcia. His recent book is René Girard, maestro cristiano de la sospecha (René Girard, Christian Teacher of Suspicion) He is also the Director of the podcast “La Caverna de Platón” for the newspaper La Razón. He has explored the political possibilities of Girardian mimetic theory in more than twenty studies and academic papers. His latest publication is “La monarquía sagrada y el origen de lo político: una hipótesis farmacológica” (“Sacred monarchy and the origin of politics: a pharmacological hypothesis”), Xiphias Gladius, 2020.

The image shows a portrait of Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu by Philippe de Champaigne, painted ca. 1633-1640.e, painted in 1648.

Translated from the Spanish by N. Dass.