Sir Roger Scruton—professor of aesthetics, author, political thinker, composer, theorist of music, ecologist, wine connoisseur, publicist and gadfly at large—passed away on January 12, 2020. As the sad news broke out, a global outpouring of tributes began, testifying to the magnitude of Scruton’s achievement and provoking questions about its meaning. Among the first, Timothy Garton Ash tweeted his sadness for the loss of a “provocative, sometimes outrageous Conservative thinker that a truly liberal society should be glad to have challenging it.”

Sir Roger’s passing is of special significance to my instution Bard College Berlin, which hosted him on two memorable occasions. It is also of personal significance to me. Though I was never a student of his, I had the privilege of knowing Professor Scruton since 1993, when a chance encounter proved to be a turning point in my intellectual path.

The Encounter

I first met Scruton in Krakow, at a conference on national stereotypes. At the time I was a student of psychology at the Jagiellonian University, gearing up to write a master’s thesis on the subject of how and why different nations perceive each other. Poland in those post-Cold War years was in the grip of regime change and a far-reaching cultural transition. Although many aspects of that transition were as contested then as they are now, there seemed to be a broad consensus: in the wake of the Soviet empire’s collapse, rejoining Europe and returning to the West where, as was said, Poland rightfully belonged was the most important political and civilizational objective. And rejoining the West meant embracing liberalism—as a political creed, economic program, and self-critical spirit.

The conference, which took place in Krakow’s newly renovated Theater Academy was imbued with this spirit. Paper after paper denounced cultural stereotypes and brought forward new examples, from the early Disney films to the latest political contests, to evidence and critique of the pervasive presence of prejudice in Western culture. With the message so monotonous, it was difficult to stay attentive.

Then came Roger Scruton. His lecture on Edmund Burke’s defense of prejudice as a distillation of collective experience sought to explain why we should not simply dismiss a phenomenon that might be constitutive of social life. Before rushing to repudiate prejudice, we had better examine its psychological origins and seek to understand its social function. Nor would repudiation help. If stereotypes are indeed necessary, repudiation would do little more than replace old prejudices with new ones.

Decades later, I still recall the sensation of hearing Scruton’s talk and the shockwaves it sent through the room. Everyone seemed to be sitting on edge, riveted by incomprehension. If the conference was a current that tended in one direction, Scruton swam against it, carried by the sheer force of his eloquent arguments delivered with a generous dose of dry wit.

Did he persuade? No, not even me, thrilled though I was to hear intellectual controversy enter the sleepy conference room, and amazed by his courage to face disapproval. Besides the many points I did not understand (my English was rudimentary back then), I could not grasp how a philosopher could seek to vindicate prejudice, whether in the age of Enlightenment or our own. And this left me with two thinkers—Scruton and Burke—to reckon with. Actually three, for Socrates soon came along to lend an interpretive lens.

After the conference, Professor Scruton and I stayed in touch in the only way practicable back then: by exchanging letters. Two years later, after receiving a stack of philosophy books that I was not in a position to read, I got an invitation to visit him in England while finishing my master’s thesis. Elated, if ill prepared for what to expect, I booked a ticket for a coach that took me across Europe to Calais, then on a ferry to Dover, and onwards to London. From London, Scruton and I continued by train to Kemble—a little town in Wiltshire, where a decrepit-looking car, stocked with books (some, to my surprise, in Arabic) waited to take us on the last stretch to Sunday Hill Farm.

Roger’s home was a stone-walled cottage surrounded by swaths of green. Three or four horses chewed quietly in an enclosure. Sheep like specks of light were scattered in the distance. Little in the picture suggested which century we were in. The cottage itself, though visibly old, was no less discrete. Offering all the modern comforts, its rooms were furnished with objects reclaimed from the ages, each playing its part in a harmonious whole. Here, I sensed, was an alternate universe where time had come to a pause, and past and present gathered to commune and peacefully cohabit. The largest space in the two-story structure was a dusky room with book-lined walls. One of these was all green with small identical-looking volumes that, years later, I would recognize as the Loeb Classical Library. Two pianos balanced the space and sealed its image as a temple of the muses.

As soon as we arrived things fell into a calm, work-focused routine—from the morning tea, to lunch, often prefaced by a horse-ride in the adjacent fields, through the solitary afternoons, to dinner-time when guests showed up and long conversations took place over choice wine and enchanted meals Roger himself cooked. It is at one of those dinners that I first met Sophie, Roger’s wife to be, and also Christina, a high-school student and the oldest daughter of a Rumanian immigrant family that Roger had practically adopted. Though long and hardworking, the days at Sunday Hill Farm did not feel that way. This was because every hour had its special purpose. Roger would take time off writing to attend to a small garden, feed the horses, bake bread, or work on whatever it was he was composing. And my presence seemed to fit seamlessly into this schedule.

A few days into my visit, Roger departed for London, leaving me alone on the farm. Having recently arrived in a country whose ways—driving on the wrong side of the road, for instance—appeared eminently strange to me, I was less than eager to be left on my own. Yet this proved an opportunity to explore the vicinity, venturing to nearby Malmesbury—a small, medieval town which (I would later discover) was the birthplace of Thomas Hobbes and a bloody playground of the wars of religion that had scarred its historic abbey.

Roaming the cottage in Roger’s absence, I was trying to peek into the mindset of this person who would invite a stranger from across the continent and give her trust and welcome. It is only then that I could take a closer look at the small study that hosted Roger’s writing desk and another piano with hand-written scores piled up on it—his first opera. The shelves in the study were occupied mostly with the books—quite a few of them!—Roger had authored on such disparate subjects as music, architecture, politics or modern philosophy. There were also a few novels. At that moment, I came to realize that I was in the presence of something extraordinary, a beautiful vista I had hitherto no experience of: a life dedicated to books and music.

Well, and horses too.

The Gadfly

In Plato’s Apology, Socrates calls himself a gadfly and describes his mission as bearing witness to uncomfortable truths. His community, the polis, he likens to a large horse, strong and well-bred, if a bit dull and sleepy, going mindlessly about its horsey business. To prick the city and his fellow citizens, shake them from their moral slumber, to summon their intellects and awaken their conscience—this, according to Plato’s Socrates, is philosophy’s calling. This calling, however, requires that its votary put himself on the line: not hide behind technical subjects or language only a few understand but enter the fray and speak about the great questions of human life in a manner that is clear and accessible (needless to add, prickly) to the community at large. It also requires the courage to face disagreement and, in Socrates’ case, even death.

Scruton’s life and death were overshadowed by controversies of one kind or another—from his work as the founding editor of the Salisbury Review that, dissenting from the mainstream at home, supported dissidents in Eastern Europe; through his spirited defense of fox-hunting; to the Brexit debates and his involvement in a Tory government commission, whose work he did not live to see in print.

In the decades that spanned our friendship, and across many embroilments, I came to understand Roger’s philosophical stance and rhetorical gestures as the work of a Socratic gadfly. Understanding, however, was not the same as accepting. And I often questioned the need for these embroilments, resenting them at times, because they seemed to muffle his message and weaken its intellectual and moral authority.

“Why alienate people?” I’d ask. “Why disturb cherished views and call forth public anger? Is this not the lesson Plato drew from Socrates’ death—that philosophy and politics do not truly mesh because the one longs for truth and the other needs lies, more or less noble? Truth, when graspable, is convoluted and complex. Reduced to a plain message, injected into the public space, it becomes lopsided and polemical, an ideology more than wisdom.”

Roger would acknowledge my passionate opinions with a gentle nod. A philosophical modernist, he had made Platonic philosophy, and Socrates as its presumed spokesman, a fertile ground for theoretical disagreement—a disagreement perhaps nowhere more visible than in his recurrent wrestling with the question of love. In practice, however, for Scruton as for Socrates, philosophy to be true to its mission demanded public engagement with all of its existential commitments and costs. The philosopher is not accidentally but essentially a gadfly; all the more so in a society that claims to be open and free. And this, as both understood, was a quest fraught with perilous paradoxes.

In Plato’s account, Socrates was sentenced to death by the people of Athens on a triple charge—of corrupting the youth, not believing in the gods of the city, and making the weaker argument the stronger. If the accusations of corruption and heresy seem clear, the last bit is puzzling. To make the weaker argument the stronger is usually interpreted as insincere sophistry: thanks to rhetorical skills and facility for crafting arguments, the sophist can make any claim prevail, no matter its inherent strength. Like a modern-day debater, he aims at victory not truth, and any argument that wins the jury’s favor has validity enough.

But there is another way to understand the indictment against Socrates that comes to light with the help of Aristotle’s ethics. For Aristotle, virtue is not the opposite to vice, but the mean between two vices. Courage, on that view, is not simply contrary to cowardice. Equally opposed to rashness and timidity, it is a kind of fine-tuning that balances the pull of two extremes. However, if virtue is a mean, it is rarely found in the middle, for each of us has particular tendencies that propel us in one direction more than the other. And so, if one person is prone to temerity while another to fear, in each case courage would look a bit different, and lie closer to one or the other pole.

If we assume that each society or historical moment has its own tendencies and ruling passions that make certain opinions more acceptable than others, to balance these, one would need to champion the weaker view—weaker not in the sense of inherently less valid, but in the sense of less popular. And this because truth, like virtue, is rarely in the extreme; and justice too would require that we weigh all sides of the argument. These sides, Burke famously argued, include not only the living but also the long dead and the yet-to-be-born. In this reading, wherever the culture is going, the philosopher’s mission is to pull the other way, and to side with propositions that, whether forgotten, or not fully realized, tend to be underestimated or ignored—and, in that sense, weaker.

“If I were born in an aristocratic century,” writes Tocqueville, “amid a nation in which the hereditary wealth of some and the irremediable poverty of others held souls as if benumbed in the contemplation of another world, I would want it to be possible for me to stimulate the sentiment of needs … and try to excite the human mind in the pursuit of well-being. Legislators of democracies have other concerns… It is necessary that all those who are interested in the future of democratic societies unite, and that all in concert make continual efforts to spread within these societies the taste for the infinite, the sentiment for the grand, and the love for non-material pleasures.”

To be a gadfly, then, would mean to raise troubling questions, and to point out aspects of social life and our humanity—the need for prejudice, for instance—that risk being overlooked or trampled on by the ideological élan for a particular opinion. It is to caution that not every change is for the better (consider climate); and what may seem like progress today—e.g., moving away from traditional forms of subjection—could yet prove to be an oppression much greater tomorrow (consider totalitarianism). It is to warn that in our hopeful enthusiasm for righting wrongs, by improving one thing we are likely to spoil another; and that, in the great complexity of human affairs, unless fully understood and carefully administered, the cure often proves worse than the disease.

Truth so discerned is bound to offend because it resists our preferences and collective instincts—precisely our prejudice. At the same time, this offense, if earnestly delivered and thoughtfully received, is what propels us toward thinking. It challenges us to consider aspects we may be prone to disregard, and to account for what and why we believe in. Only by listening to those who question our certitudes, Mill argued in On Liberty, can ideology be countered and dead dogma quickened into vital truth. So much so that if liberal society did not have an earnest opponent and conscientious dissenter—its own Socrates—it had better invent him.

Mounting a well-argued opposition to just about every progressive creed—multiculturalism, individualism, atheism, globalism—Scruton was no less a gadfly to the conservatives with whom he otherwise identified. His vision of conservatism, centered on conservation and green politics, was as much a rebuke to Thatcherism as to the Blairite consensus that replaced it. He did not shy away from instructing US Republicans on the good of government. And his vision of the university challenged the anti-establishment zeal of the established professoriat as well as the technocratic Cameron reforms that collapsed the ministry of Education under Business. Whatever his audience, Scruton sought to stir thinking, not applause.

And yet another paradox lurks here. If philosophy’s role is to serve as counterweight for political and intellectuals fads, is the philosopher then necessarily a contrarian – one, whose mission is to dispute whatever most people happen to agree on, so a creature of the crowd after all? A different way to pose the question: is the thinker’s role to play the sceptic and critique popular opinions; or should he also strive to put something fuller and more coherent in their place? If the former, he’d be forever a debunker, always against but never for anything (other than his own importance). And if the latter, is he not in danger, while contesting the dogmas of others, of becoming a dogmatist himself?

Well-aware of these tensions, Scruton deemed them unavoidable. While playfulness and irony, alongside other literary tropes, offered partial solutions, his main recourse was, once again, Socratic—to live his life as an example and seek to practice what he preached. This informed both his decision to leave academia and embrace country life, and the autobiographical turn his books took in the late 1990s. While his chief philosophical purpose was to recover what he called the soul of the world, Scruton recognized that this can only be done in living out his commitments and bearing personal witness to the propositions he put forward. It required that he become, in the original sense of the word, a martyr.

μᾰ́ρτῠς • (mártus) m or f (gen. μᾰ́ρτῠρος) — A.Gr. witness.

Going Home

Among the more puzzling of Plato’s works is a short dialogue called Crito. Set in the eve of Socrates’ execution, it opens as the eponymous Crito, an elderly gentleman of means, comes in the dark before dawn to visit Socrates in prison. He has made all the preparations: bribed the guard, gathered resources, and arranged for a boat to steal his unjustly convicted friend away from his doom.

The conversation that ensues is Socrates’ attempt to reason with his childhood buddy and persuade him (and possibly himself, as well) that submitting to the judgment of the Athenian people is the right course of action; and so that dying as a citizen is preferable to living as an exile. In the course of the conversation, Socrates impersonates the Laws of Athens to deliver arguments that sound patriotic to the point of chauvinism. Invoking his young sons, his plea on behalf of the Laws recalls his own decision, made in advanced age, to become husband and father.

The conversation that ensues is Socrates’ attempt to reason with his childhood friend and persuade him (and possibly himself, as well) that submitting to the judgment of the Athenian people is the right course of action; and so that dying as a citizen is preferable to living as an exile. In the course of the conversation, Socrates impersonates the Laws of Athens to deliver arguments that sound patriotic to the point of chauvinism. Invoking his young sons, his plea on behalf of the Laws recalls his own decision, made in advanced age, to become husband and father.

Socrates’ declared allegiance to country and family stands in some tension with the project of philosophy, to which he pledged his life. No respecter of countries or borders, philosophy’s object is to interrogate all human laws and attachments—love itself—in light of a universal standard. Nor does Plato’s Socrates usually come across as a devoted father. More than his biological children, his conversational companions, indeed conversing itself, seem to be the focus of his affection. Is a philosophical life compatible with being a patriotic citizen or responsible paterfamilias, Crito prompts us to ask. How can one be committed to universal truth, or to probing every kind of social convention, and, at the same time, stay true to a particular community and faithfully observe its flawed laws, questionable practices, and harmful judgments, even unto death?

After his talk at that fateful 1993 conference, I came up to Prof. Scruton and we exchanged a few words. “I want you to meet a student of mine” he said and introduced me to Joanna, a Polish woman my age who grew up in the US, where her family was exiled in the aftermath of the 1981 military crackdown on the dissident Solidarity movement. One of Scruton’s best students at Boston University where he taught at the time, Joanna had come along to the conference as a first opportunity to revisit her country of origin. Though at this point she had spent more than half her life in America, the journey to Poland was a homecoming—a charged and meaningful moment that Scruton took as seriously as she did, and which first announced what would become a recurrent theme of our interactions.

Over the decades that followed, Roger did all he could to support my philosophical wanderings; from proofreading my first essays in English and writing letters of recommendation, to patiently enduring my own attempts at playing the gadfly, usually directed at him. Scattered across time and space, and whatever their occasion, our conversations would often end on the same note—the importance of home, and the duties of homecoming, a message that became all the more troubling as my English waxed and my native tongues waned. “You should go home,” he repeated whenever and wherever we met. “Remember to go home.” “What is home?” I’d reply, as it were, Socratically. “Is it a place or a principle, or a figure of speech? Why can’t the world be our home?”

Surely, for Scruton too this had been a question. And he was far from believing that one’s home is, in any simple sense, the place or circumstances of one’s birth. In his own wanderings, he had moved light years away from his lower middle-class origins and his father’s socialist convictions, as he later did from the urban pieties of the academic elite to which he belonged by learning and habits.

Roger deeply loved French culture, and was intellectually at home in Germany. He taught for years in the US where he considered emigrating at some point. He had a soft spot for the countries of Eastern Europe which haunted his novels, and whose decorated hero he had become; and he had a special bond to Lebanon where he first learned Arabic and witnessed civil war as a young man. Like his Englishness, Scruton’s endorsement of rural ways was qualified by profound erudition and cosmopolitan tastes. Nor could any party claim him—or wish to claim him—without reservation. If he had one strong identification, it was with being an outcast and heretic.

And yet, the first law of Scruton’s ethics was the imperative to settle down—espouse an ethos, assume one’s station, and honor one’s roots, despite the estrangement and ironic distance one might feel about the whole thing. Without settling-down, thus acknowledging that one’s view is necessarily a view “from somewhere,” one is a free-floating, ineffectual person and, in an intellectual sense, a dishonest man. At the same time, without the distance and estrangement that thinking stimulates, one’s home would not be a reasoned perspective or self-aware choice, but an unreflective product of accident and custom.

As for Plato’s Socrates, the philosophic quest as Scruton understood it, was not to deconstruct one’s love for family and country, but to give a full account of, and thereby deepen, that love. Indeed, the more difficult it is to define and maintain a notion of home in the modern world, the more important it becomes to insist upon it. This holding on—the capacity and courage to own up to one’s particular commitments, despite or perhaps because of all the reservations one can feel about them—is what truly distinguished the philosopher from the rootless sophist, whose only standing commitment is to unbounded love of power, however obtained.

In Scruton’s diagnosis, most originally delivered as an homage to French viniculture and philosophy, our age is drunk on universalisms demanding that the same principles, analogous practices and mass-produced tastes apply equally everywhere, with no regard to differences of place, history, social conditions, and even species. If universalistic creeds are like strong distillates that—stripped of specificity or local flavor, and detached from communal context—aim for immediate inebriation, Scruton’s proposed remedy was not abstinence or anti-intellectualism, but thoughtful connoisseurship of drinks and ideas.

Such a connoisseurship must begin with the recognition that, if the desire for universality is a heroic aspiration and philosophy’s very raison d’être, it is also a dangerous temptation. While this desire may expand our intellectual horizons, ennoble the arts, and elevate civic sentiments, it cannot be our home. For it demands that, in the name of disembodied abstractions, we abjure the attachment to particular persons or peoples, and repudiate everything we may consider our own—the ways and devotions that distinguish our form of life, and define who we are, individually and collectively.

The weaker argument Scruton made it his life-long mission to uphold was the importance of loving one’s home and protecting the environment, both natural and human, spiritual and physical that sustains it. He shared with many on the left a poignant sense of the destruction wrought by globalized capitalism. Yet he challenged the self-serving mantra of globalized elites that the only effective response is the ever-greater outsourcing of civic agency and decision-making to supranational structures unmoored from any organized community of citizens that can hold them to account.

More soberly, Scruton insisted on the need to revive allegiance to local traditions and to common practices, which alone lend meaning to high-sounding words and abstract ideals. Only by coming together and by drawing on shared modes of thinking and feeling can freedoms be substantiated, the environment protected, and effective solidarities fostered. This insistence went together with a vision of England as a community bound by law and sense of accountability—less a physical location than a spiritual landscape marked by distinctive virtues and sense of beauty. It is to the task of protecting this beauty that his last efforts were dedicated.

“We should recognize,” states the posthumously published report Scruton drafted for the government commission on Building Better, Building Beautiful, “that the pursuit of beauty is an attempt to work with our neighbours, not to impose our views on them. As Kant argued in his great Critique of Judgment, in the judgment of beauty we are ‘suitors for agreement,’ and even if that judgment begins in subjective sentiment, it leads of its own accord to the search for consensus.”

*

My last meeting with Scruton in October 2019 was a lesson in dying, the preparation for which, Plato’s Socrates claimed, was philosophy’s special task. Roger spoke about his mysterious illness and the pains that had become his constant companion—but much more about the gratitude he felt for his life and for those who helped shape it.

“It is clear” he mused serenely, as though considering some abstract matter “that things cannot go on forever. I have said all I had to say, wrote all the books I wanted to write. I’m ready, I suppose.” As if casually, he added: “But life is so sweet…”

He died at home.

Ewa Atanassow is professor at Bard College Berlin. Her area of expertise is the history of social and political thought, especially Tocqueville, as well as questions of nationhood and democratic citizenship. She is the co-editor of Tocqueville and the Frontiers of Democracy, and Liberal Moments: Reading Liberal Texts; and the author of Liberal Dilemmas: Tocqueville on Sovereignty, Nationhood, and Globalization, forthcoming from Princeton University Press.

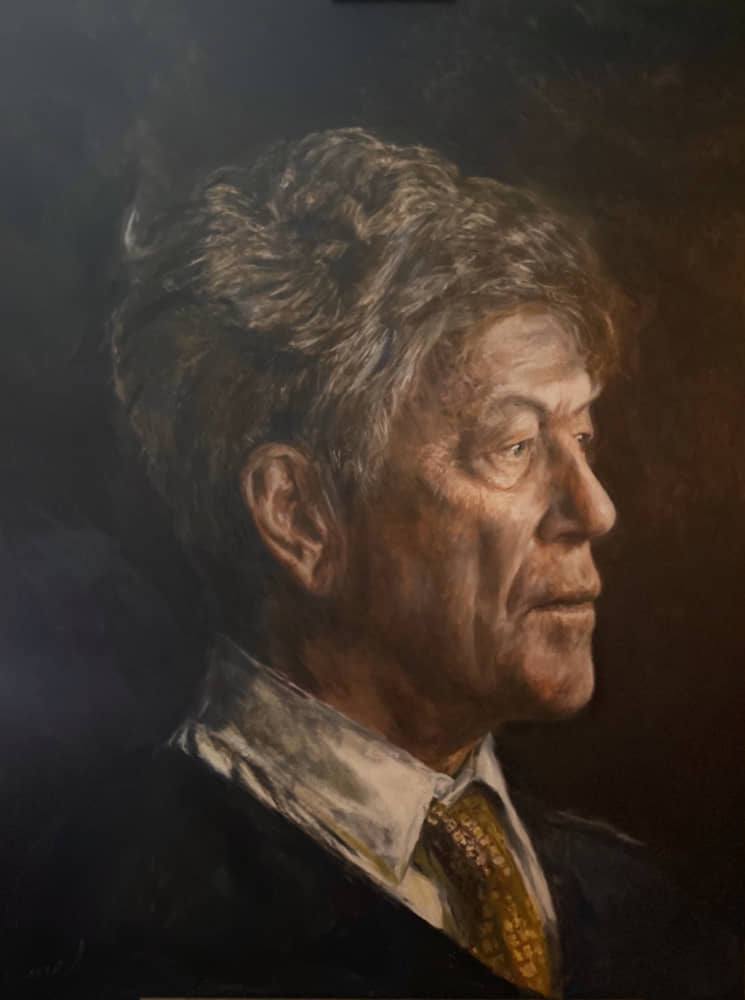

The featured image shows, “Portrait of Sir Roger Scruton,” by Vernice Satinata; painted in 2020.