What does beauty have to do with politics? Contrary to what it seems, both have a lot to do (especially when the ugly and the vulgar reign). Such is the reflection that this article raises.

“People have never been moved by anything but poets, and woe to him who does not know how to raise, in the face of poetry that destroys, poetry that promises,” proclaimed, ninety years ago, a certain tribune whose remains have recently been desecrated by the government and whom I have described, in a recent anthology, as a “poet politician.” It is true what he says—metaphorically understood, of course—about people and poetry. But it is not an easy thing to do. It is not evident that a poetic politics manages to rise above the sad prose that usually overshadows the political space, wrapped as it is in the din of passions, high and noble, sometimes, but also vile, and much more frequently. It has always been like this. Even in the times when the res publica knew its highest brilliance—Greece, Rome, the Italian Renaissance—the life of the City has been mired in the mud of turbulence, intrigues and vileness that convulse it.

In the best of cases, political action can, as I said, be noble, courageous, heroic—but as for beautiful, what is said to be beautiful, is not. What it was—and one day perhaps will be again—was an encourager, a promoter of beauty. It is enough to go to the Louvre, to visit the Prado, to pass by the Hermitage, to approach the Uffizi—it is enough to visit the inexhaustible rosary of palaces, temples and monuments that populate our Europe to verify to what point the yearning for the beautiful palpitated in the courts and cities of other times.

Was the “aesthetic taste” of our ancestors so developed, then? Was that so powerful a taste that the lords of liberalism and its democratic masses seem to have lost today?

No, it was not any “aesthetic taste” that, during millennia, spread in the world such a profusion of art. It was a “historical taste;” let’s put it that way. It was an eagerness to endure in time, to defeat death, to defeat it in the only way it can be defeated—by taking root in the collective memory, leaving engraved in stone, inscribed in marble, captured on canvas, written in words, the mark left by men in their passage through time.

What about our passage through time? How will we, the modern and postmodern, pass through it?

On what stone, marble or canvas will our mark be stamped? What monuments, what works of art will we leave? None, of course. The art that could be ours has vanished. In its place the ugly, bland or vulgar is deployed—from painting to architecture, even in our ornamentations and including music. If something manages to escape its encirclement, it does so sporadically, exceptionally. For the first time, beauty has ceased to mark the times. Except for a few rare exceptions, the only great art we know is the one in museums or in palaces, temples or ruins from other eras. Crowds of tourists run around and take selfies in front of what their era will never give them. Once the visit is over, they return to their sad neighborhoods and their comfortable apartments. Sitting on their sofas, they turn on the television.

Why has Beauty Faded Away?

Have we, then, lost our “aesthetic sense,” just as the blind man loses his sense of sight, or the deaf man loses his sense of hearing? No, it is something else. It is not any “sense” that we have lost, it is not any “cognitive faculty” that has been adulterated. The “aesthetic sense” is more than deployed when we deposit on the works of the past that contemplative, passive, inert look, with which we admire works that will leave us all the rapture we want—”oh, oh, how lovely, how magnificent!”—but they will never make Life, palpitating in them, impact us with the thrill of the beautiful.

It was beauty, instead, that struck those who crowded the Greek temples and theaters, those who crowded the Roman forums and circuses, those who crowded the cathedrals and medieval squares, those who sang the verses of our Romances, those who prayed in the Renaissance or Baroque churches, those who went to the comedy theaters, or those who walked through the convoluted alleys whose beauty, so simple, so poor even, still strikes us, the moderns, who will never be shaken by beauty when we drive through the jumble of our urban highways, when we pass without praying in front of our churches that look industrial warehouses, when we enter our industrial estates and sports centers, when we shop in our supermarkets, when we stay (oh, of course, comfort and conveniences, and rightly so, fascinate us! ), when we stay in the reinforced concrete hives that line up, haggard and sad, in the peripheral or central neighborhoods of any urban monster of any country in the world.

“The Greeks, that people of artists,” said Nietzsche, speaking of those who were undoubtedly artists to the highest degree. Not because most of them practiced any art, but because beauty was like a force that, bursting into life, gave it meaning, either through the words of tragedies and foundational texts (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Hesiod, Homer), or through the marble that made up the temples and raised the divinities before which those people recognized themselves.

But let’s leave the Greeks and come back to us—why don’t we recognize ourselves today in beauty? Because there is none! It is as simple as that. But why is there no beauty? Why have we stopped engendering beauty? For one reason—because the beautiful constitutes the highest expression of the spirit, and the spirit is for us a secondary, inessential thing; important only for leisure and amusement, even if it is a lofty, sublime amusement.

Let’s put it another way. If, contrary to the ancients, we do not create or recognize ourselves in beauty, it is because where they recognized themselves was neither in a leisure activity nor in an “aesthetic beauty.” What was at stake was a living beauty, woven on the background of a mythical space, of a sacred breath that, permeating everything, made “something”—an intangible, superior “something”—float in the air of all societies, of all times prior to modernity.

How can beauty reign when nothing like it floats in our air? How can it reign when, for us, nothing is valid unless it bears the mark of the rational? Nothing moves us outside of our prosaic wandering, our daily work and eating in order to, in the end, die. No myth sustains us. No sacred myth, it is necessary to specify—because the other myths, in the banal and negative sense of the term, we have aplenty: Money, Market, Utility; such are their names; those myths about these absolutely indispensable things, but not as foundational myths, not as instances bearing a meaning that they are incapable of giving.

And if nothing gives meaning, if nothing shapes or signifies the splendorous mystery of the world; if nothing expresses that superior, intangible and ineffable “something”—believers call it God—everything then collapses, and beauty finds no place to throb, and beauty hides, ceases to shine, and ugliness takes its place.

Our Paradox

However, our situation is still curious. Never as today, when it shines the least, has beauty been so necessary. Not only to fill the void left by its disappearance. Not only so that someday we may once again be awed by the beautiful things—but alive, but ours—that we may create again. If we need beauty, it is for something even more important. To save us. To give meaning to a life that no longer has meaning.

We have lost our way and our destiny. But, if we have fallen into it, it is for something that, in itself—and the paradox is immense—constitutes an adventure.

A thousand scientific reasons explain—and this is to be celebrated—a thousand questions about how the things of the Universe and of matter, of physics and chemistry, of biology and of the organism function and are articulated, how they are structured. But if such reasons explain the how, none explain nor can explain the what. What is this? What is this, this flower, this mountain, this sea, these trees, these men? What are these men who, living and dying, thinking and speaking, pronounce words that designate and give meaning to the flower, the mountain, the sea, the trees—to everything that, without words to name it, would never be: it would only be there?

As the Universe was during the billions of years of the Great Silence that covered everything—not even God spoke, not even anyone invoked Him or thought about Him—until certain apes decided to get down from the trees, stand up on two legs and emit the grunts that would become the words that, signifying, began to give meaning, to infuse being.

When all this is more than understood and known, what can such things as God or the gods, the sacred breath, the space of the mythical still do? They no longer paint anything; or so at least our times believe. And yet, no. Of course, they paint or can paint. Much even. For a simple reason. Because knowing everything we know about the how of things, we still know nothing about their what and their why, about their meaning and our destiny. What is this, what is that? What is the meaning of our life? Why and for what purpose do we live and die?

In reality, our lights are even dimmer than before. We find ourselves much more helpless than when a thousand images, a thousand flashes, a whole imaginary filled the abyss of existence. It filled it falsely, it is true, as far as the materiality of things is concerned; but it filled it significantly as far as its meaning is concerned. Today, on the other hand, alone and with our reason alone on our shoulders, we do nothing more than wander lost in the abyss.

And yet… Yet we have Art: “We have Art,” Nietzsche said, “in order not to perish because of Truth.” In order not to perish because of that rationality, that scientificity, absolutely indispensable—let us repeat it again and again—but which stiffens our soul.

Does Art remain for us? It would remain for us, rather, if we were able to embrace the challenge it implies. We would be left with Art—that prodigious fiction in which the imaginary displays the most authentic significance of the real—if Art became our watchword, our flag planted in the center of the City. “Artocracy,” Filippo Tomasso Marinetti called it.

This would imply a huge awakening, an artistic and spiritual rebirth as great as that of the other Renaissance. Both on the part of the creators and on the part of a society that, incapable today of considering the empire of ugliness as a catastrophe, limits itself to shrugging its shoulders when it passes by our urban eyesores, or to smiling—but mockingly—when it discovers the monstrosities of our “contemporary art.”

To do this, it would also be necessary for those who, full of identity fervor, fight in the City to include in their proposals and actions the idea—just that, the idea, and it would be a lot—that what is at stake is not only Bread and Justice, as said before; it is not only the unity of the Homeland and its ethnic and cultural continuity; it is not just the fight—exclusively defensive, today—against woke delusions. All of those things are absolutely necessary, it goes without saying. But, beyond them, it is equally necessary to launch existential and cultural ideas and projects in which a whole new way of being and existing is reflected. Ideas and projects that make us aware of the meaninglessness of a life that, crushed, among other things, by the ugly and the vulgar, is gradually falling into the abyss at the bottom of which the face of death appears, smiling like an advertisement.

But not “death by catastrophe, but puddles in an existence without grace or hope. All collective attitudes are born weak…. The life of the community is flattened, it becomes dull, it sinks into bad taste and mediocrity,” denounced, ninety years ago, the tribune who said that only poets can move the people.

Javier Ruiz Portella, journalist, essayist, writer and publisher, in Spain, whose recent book is N’y a-t-il qu’un dieu pour nous sauver? (Is There No God to Save Us?). This article appears through the kind courtesy of La gaceta de la Iberosfera.

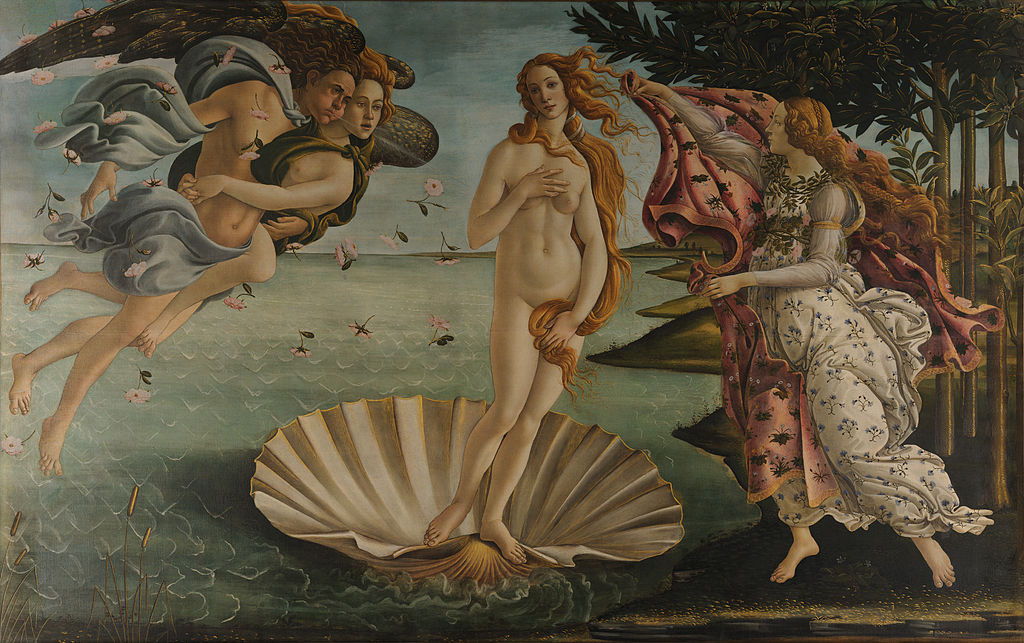

Featured: The Cestello Annunciation, by Sandro Botticelli; painted ca. 1489 to 1490.