“In nature, in the cosmos, there is a divine, sacred dimension. In this sense modern “neo-paganism” is a hasty conclusion or, at least, a transitional phase” (Ernst Jünger, The Coming Titans).

When one speaks of the ideas of the “ND” (Nouvelle Droite/New Right), the intellectual current that emerged in France in the 1970s, there is a recurring theme: its position on the question of religion and in particular its option for “paganism.” What exactly does this paganism mean? Where did it come from? Are the ideas of the ND incompatible with a Christian confession? Where, intellectually speaking, has the paganism of the ND led? Here are the answers of someone whose intellectual formation is inscribed in the Nouvelle Droite/New Right and who, nevertheless, is Catholic. A text for debate.

The “Nouvelle Droite/New Right” was known—and is now less and less known—as the school of thought, led by Alain de Benoist, that was born in France in the 1970s and which, since then, has described a trajectory similar to that of meteors: on an unknown course, illuminating the night firmament, attracting attention, also arousing fears—even omens of catastrophe—and, along the way, shedding fragments of disparate behavior, depending on the atmospheric conditions. I am one of those fragments. I entered the intellectual orbit of the “Nouvelle Droite / New Right” (hereinafter “ND”) around 1982. I read absolutely everything published by the ND (which was and has continued to be a great deal), I attended its international colloquia and summer universities (very few Spaniards passed through there) and, for some time, I tried to see that here, in Spain, something similar to what arose there might emerge. This is to underline that these lines, which are intended to be a dispassionate analysis, nevertheless contain an important part of personal confession.

The ND and its Context

The ND was so called because it was a way of thinking different from what was in force at that time—in the 1970s and 1980s—which was the ideological monopoly of the left. It must be repeated: a way of thinking; that is, an intellectual attitude, not a political attitude. Since it was not left-wing, it was called “right-wing.” And since it did not fit into the usual molds of the ordinary right either—because it was neither traditionalist nor liberal—it was called “new.” Given the oppressive atmosphere that the Marxist intelligentsia had imposed on European thought and on the media since the 1960s, the attitude of the ND, uninhibited, intelligent and without complexes, represented a real breath of fresh air for many temperaments, and especially for those who, being by convictions on the right, needed (we needed) to think things in a new and deeper way.

What the ND contributed was a very extensive and intense critique of contemporary civilization, and it did so with a very broad philosophical base—there is no author whose ideas have not served it well, from the Frankfurt School to the great French reactionaries, and from the mystics of medieval Germany to postmodern sociologists—and with a properly multidisciplinary projection; that is to say, it applied to economics as well as to psychology, biology as well as to politics. Someday we will have to recapitulate this immense work, ignominiously reduced by hostile critics to a mere emanation of the “radical right,” and we will see that it is a real reservoir of ideas. As with all deposits, here too there are inexhaustible veins and others that are soon extinguished; galleries of infinite expanse and others that lead to dead ends; valuable materials and others that vanish on contact with the air. In any case, the deposit is there: in the huge collection of texts gathered in the volumes of the journals Nouvelle École, Éléments or Études & Recherches, not to mention the numerous publications published on the periphery of the ND, as well as in the overwhelming books by Alain de Benoist, and in the very long list of texts that have emerged around this initiative. It is a pity—and this says a lot about our times—that most of those who criticize the ND do so without having read a single page of this properly encyclopedic work.

What were the main lines of the critique of the ND? Synthesizing to the bare essentials—and, therefore, simplifying to the point of abuse—we can describe them in three vectors. The starting point was a triple refutation. In the first place, the reprobation of the social culture imposed since the 1960s—much before, in fact—by the left-wing intelligentsia, a social culture that translated into a singular mixture of forced egalitarianism, ideological materialism, generalized moral abdication and infinite hatred towards European identity. Secondly, a deep nonconformism towards the economic civilization imposed by the capitalist order in the West, that type of civilization where no other form of individual or collective life is understood, except through the selfishness of “best interest” and “profitability.” Thirdly, a very characteristic issue of the final years of the Cold War: the weariness of a Europe subjected to the despotism of a bipolar world and the anxious search for its own, European, way to regenerate the spirit of the old continent in the new and threatening world of the great superpowers.

From these three points of origin, the reflection of the ND unfolded in vectors that led naturally to identify; first, the root causes of the evil being criticized, and then to try to think of an alternative to the situation.

The critique of the cultural model of the left led to a dissection of egalitarianism, namely, that dogma of the essential equality of human beings. Such a dissection departed from the usual liberal critique of egalitarianism (that equality undermines efficiency because it inhibits ambition) and focused instead on underlining the anthropological foundations of difference, both among men and among peoples; difference which, in the discourse of the ND, was not so much aimed at creating a new legitimacy for this or that hierarchy as at proposing ways of thinking about diversity: of social functions within a community, of cultural identities, of forms of development, etc.

The second point, the critique of economic civilization—and its corollary, technical civilization—led to the identification of individualism as the origin of the process: Individualism, that is, the conviction that the ultimate horizon of all reflection and action is the individual; his autonomy identified as his “best interest;” his search for happiness interpreted in terms of material success, according to a pattern of behavior that extends from economic life to any other field; from politics to family relations. The need to propose a critical alternative to individualism—without falling, on the other hand, into the annulment of the individual typical of egalitarian systems—led to the search for an alternative sociality, a task in which materials as diverse as the “tribal” sociology of the postmodernists, Christian personalism or the theses of Anglo-Saxon communitarians were brought together: systems of life in common, where the person and the group are not antithetical elements, but complementary realities.

As for the third vector, which stems from dissidence with respect to the world order born of the Cold War, it took the form of a critique of universalism—although it would have been more accurate to speak of “globalism”—which led to a rejection of the idea of a planetary convergence around the North American model and the proposal of a sovereign Europe in the military, diplomatic and economic spheres, the defense of the cultural identities of all peoples, and an alliance of this sovereign Europe with the Third World.

These are, roughly speaking, the elements from which the thought of the ND developed. It would be too long to go into the derivations of each line; for example, the critique of the concept of “humanism,” the distrustful look towards technical civilization, the recovery of elements of the traditional ecological discourse, the proposal of an alternative conception of democracy and the State, the critique of nationalism as a “metaphysics of subjectivity,” etc. It would also be excessive to enumerate the theoretical materials that contributed to support this work; all of them can be found in the publications of the ND and to which we referred.

Criticism of Christianity

Within this work, there was a specific line of reflection that some consider fundamental and others secondary, but which in any case has had the virtue (or rather the defect) of absorbing attention to the point of obscuring the rest of the theoretical ensemble of the ND: the question of religion, resolved in an acerbic criticism of Christianity and in a vindication of a new kind of paganism.

Before explaining this point, it is necessary to point out that, in reality, the sources from which the attitude of the NR towards religion draws are very plural, very diverse, also contradictory: among the names that supported the birth of the Nouvelle École—the first great theoretical review of the movement—there are, for example, quite a few Christians. These sources, moreover, have not led to a homogeneous position, but to different attitudes, which, in turn, have undergone modifications over time. A perfect example of such heterogeneity is the survey, “Avec ou sans Dieu / With or without God,” organized by the magazine Éléments, where different authors related to the heteroclite galaxy of the ND (including myself) and explained their position on the matter. More than fifty years after the ND began its work of reflection, the balance in this matter is very abundant in terms of points of view and potentially rich in openings to other currents, but rather disappointing if one is looking for a solid and well-defined intellectual position. The “pagan drift” is an important feature of Alain de Benoist’s thought and, in this sense, it can be considered “canonical” with respect to the whole of the ND, since he is undoubtedly its main theoretician; but not even in this author can one speak of a continuous position over time, but rather of an evolution that is not always predictable. For the rest, the different strands that built the framework of the thought of the ND on religious matters have ended in dead ends or in an uncomfortable impasse. And this is what we must now examine.

When does the polemical question of Christianity—of anti-Christianity, rather—enter into the general discourse of the ND? It enters at the moment of genealogies, when we try to find the intellectual origin of egalitarianism, individualism and universalism. Christianity, in fact, has an important egalitarian component, since it endows all men equally with a soul of identical value for all, regardless of the place each one occupies in the world of the living; and all men equally will be submitted to divine judgment. Moreover, the Gospel message, abundant in formulas such as “he who humbles himself will be exalted and he who exalts himself will be humbled,” or “the last will be first,” seems designed to nourish subversion. Christianity also has an individualistic component, since salvation is entirely individual, affects only and exclusively the soul of each person and places man’s relationship with God on an eminently personal level. Christianity, finally, is a universal religion, where, as St. Paul preaches, after Revelation there are no longer Greeks or Jews, barbarians or Scythians, but we are all one in Christ, so that belonging to a community is expressly devalued and, in its place, a properly universal consciousness emerges: We are all one, in fact.

In this act of pointing to Christianity as the origin of the essential values of the modern world, it is easy to trace the influence of Nietzsche, both in the Genealogy of Morals and in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. But, in the specific case of the ND, perhaps even more important was the influence of the positivist philosopher Louis Rougier, who had recovered the old allegory of the Roman Celsus against Christians. Thus, it was that towards the end of the 1970s, Christianity was characterized in the discourse of the ND as “the Bolshevism of antiquity.” In an environment such as that of European culture in the 1970s, where a Church disrupted by the Second Vatican Council was openly playing the “progressive” card, this criticism seemed to be quite in line with reality.

Let us talk a little more about Louis Rougier, because his role in this story is important. With Rougier (1889-1982), the logical empiricism of the Vienna circle entered the early ambit of the ND (early 1970s). This source brought, from the outset, a scientistic attitude towards reality: empirical truth—read, experimental—became an efficient alternative to the prevailing “ideological” truths of the time, generally derived from the Marxist-Leninist paradigm. Remember that this is the time when biology seemed to be dominated by the environmentalist model of the Soviet Lyssenko and psychology was dominated by Freudian psychoanalysis, both schools which, in their translation into social philosophy, coincide in proposing egalitarian doctrines. As opposed to these doctrines, the ND claimed, in psychology, the experimental work of Eysenck, Jensen or Debray-Ritzen, and in biology, the contributions of ethology (Lorenz, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, etc.) and of the first sociobiologists (Wilson, Dawkins), who coincided in proposing differentialist, i.e., non-egalitarian, models. From this period dates also, by the way, an old error of the interested critics of the ND—the assimilation between their positions and those of sociobiologists. But the ND very quickly distanced itself from sociobiology because it considered that its approach was nothing but a reductionism to genetics. In its place was adopted the vision of Konrad Lorenz, based on a much more elaborate, non-reductionist philosophical anthropology, which perfectly integrated the biological dimension of the human and his cultural dimension: the anthropology of Arnold Gehlen.

From the scientific point of view, it is obvious today that the ND was betting correctly: genetics has proved to be a key discipline, while Lyssenko’s environmentalist delusions are no longer remembered. However, this position had a drawback from the philosophical point of view: it made the discourse of the ND gravitate around a scientistic materialism that vetoed an objective approach to the sacred. And this, despite the fact that some of the inspirers of this scientific position were avowedly Christian, as in the case of Konrad Lorenz.

Louis Rougier is also important in the forging of the discourse of the ND for another contribution, this one in the field of the history of political culture: his book Du paradis à l’utopie (From Paradise to Utopia), which is an explanation (very remarkable, by the way) of how the egalitarian messianism of the left derives directly from a secularization of Christian eschatology, from an earthly-ization of the message of salvation. The thesis of From Paradise to Utopia is, in general terms, unassailable: most of the redemptorist concepts of the left in general and of Marxism in particular find their antecedents in equivalent concepts of the Christian heritage. Thus, Providence is transformed into the Necessity of history and the ultraterrestrial Paradise is transmuted, through utopia, into paradise on earth. The fact that this supposed paradise has led to the Gulag only goes to show the absurdity of the transposition and the correctness of Rougier’s criticism. Now, from this point on, Rougier’s thesis reproaches Christianity for carrying, in germ, the seed of subversion; and in this sense, he will recover—later on—the warnings of the Roman Celsus against the threat that Christians represented for the empire. If Christianity could be secularized into a revolutionary ideal, it is because the Gospel message carried within itself this virtuality. This is the aforementioned characterization of Christianity as “the Bolshevism of antiquity.”

In this way, the anti- or post-Christian line of thought that stemmed from the 19th century came to connect with a general philosophy of scientific matrix, very typical of the 20th century. The “pagan rebellion” that can be traced in certain streaks of German and French romanticism, in the philosophy of Nietzsche and even in works such as Wagner’s (before his Parsifal), went hand-in-hand with the logical critique of the Christian mental model and ended up giving birth, in the ND, to a position of simultaneous rupture with Christianity and with modern ideologies, which were seen as nothing but secularized prolongations of the evangelical message.

The Weakness of the Philosophical Critique of Christianity

Now, to focus the critique of modernity on Christianity was an intellectually risky operation. First, because Christianity, although it is not only a doctrine of the afterlife, is above all a doctrine of spiritual salvation, in such a way that its concepts cannot always be understood as principles of an intellectual-ideological order, ready to be applied materially to the social or political terrain. It is true that preaching an equal soul for all men can be understood as a form of egalitarianism, but it is also true that, according to Christian doctrine, some of these men are saved and others are not, and there are few things less egalitarian than this difference. On the other hand, the theme of man created unanimously in the image and likeness of God is opposed by the parable of the talents, which is a metaphysics of inequality.

The same is true of the other modern “ideologemes” that the critique of the ND attributes to Christianity. For example, in Christian discourse, the theme of individualism—the soul is an individual attribute and salvation is also a matter of the individual—is opposed by the theme of the negation of individuality, expressed in terms that lead to proposing the radical renunciation of all things in the world. The same contradiction is found in the theme of universalism: if in the proclamation that “we are all one” there is an evident affirmation of the unity of believers above the earthly powers, it is no less true that this unity leaves out non-believers; and, on the other hand, the doctrine itself exposes a clear separation of the earthly and spiritual spheres, according to the formula “to God what is God’s, and to Caesar what is Caesar’s.” In other words, Christianity can be reproached for one thing and also for the opposite. Focusing the discourse on only one of the facets means deliberately hiding the other and, in that sense, falsifying the whole. To put it bluntly, it is as if the ND, in its critique of Christianity, were describing an object other than the one it intends to criticize.

Let us stress the question of egalitarianism, which is crucial. In general terms, the identification between Christianity and egalitarianism suffers from an initial error, namely—from metaphysical equality does not necessarily derive physical egalitarianism. It is true that the Church, in other times—and precisely in the 1970s—did not fail to fall into this error, allowing or encouraging (depending on the strands) that the doctrine of metaphysical equality (all men are brothers because they all have a soul that is an equal child of God) be “recovered” by the dominant egalitarian discourse (all men are equal). But what the ND does is methodologically debatable: it does not combat the error of these ecclesial strands, i.e., it does not examine the initial premise, but takes it as valid—that is, it accepts the identification between metaphysical equality and political egalitarianism—and from there deduces a general critique of Christianity as the matrix of all egalitarian thought. All subsequent discourse is affected by this methodological error of departure. The results are intellectually very fragile: the equality of souls before God cannot be identified with the equality of men in the State, if only because, in the first case, some are saved and others are not; neither can Christianity be identified with egalitarian thought, if only because, historically, all egalitarian thought has tended to burn down churches and de-Christianize those societies where it triumphed.

In the end, the ND is criticizing a false, phantom Christianity, a mistaken idea of Christianity. Naturally, it could be objected that what the ND criticizes is not Christianity as a religion, but Christianity as a worldview. But the objection itself betrays the error: Christianity is first and foremost a religion, and it makes little sense to criticize an object as something other than what it is. Another thing is that forces arising from the Church itself have desacralized Christianity—for example, turning it into a very materialistic theology of liberation. But here the error is in the executioner; that is, in those who have executed the desacralization, not in the victim, that is, in the desacralized Christianity.

In all this, let us emphasize that the thesis that modernity is a secularization of religious concepts remains valid: modern discourse is really incomprehensible if we do not understand it as secularization. Here we are approaching that Schmittian formula of “political theology”: modernity transfers to the political terrain numerous concepts that were once part of the theological terrain. That is to say that the general pattern of Du paradis a I’utopie (From Paradise to Utopia) is objectively correct, as is much of Louis Rougier’s analysis (think of Le génie de l’Occident /The Genius of the West). But what can be deduced from this pattern of analysis is not so much the secularized triumph of Christianity as its corruption: the supernatural has been translated as natural and thus its essence has been distorted.

The Problem of Paganism

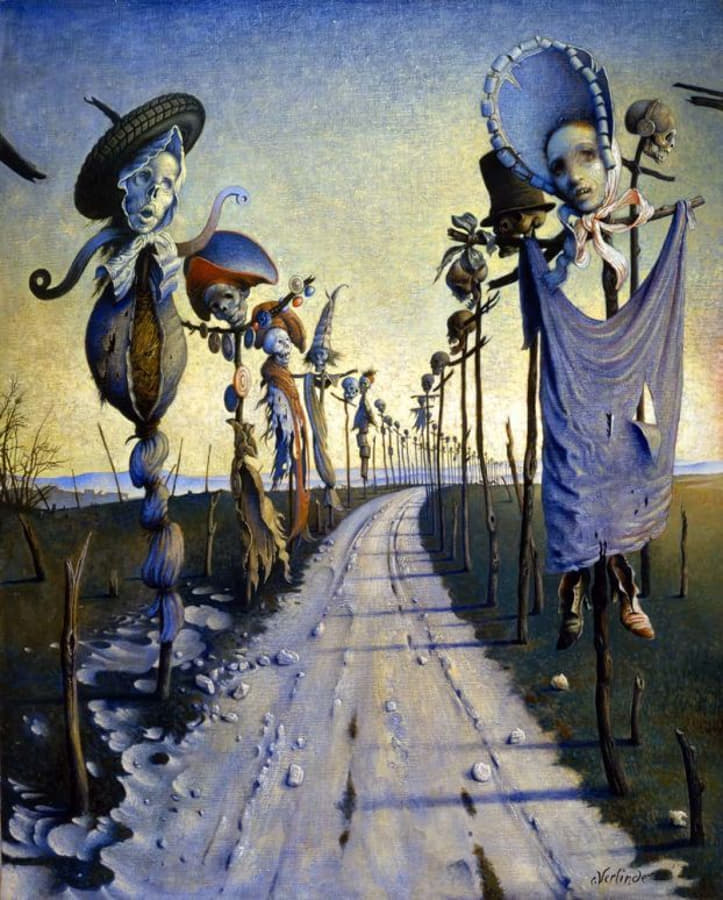

Faced with this Christianity secularized by modernity and supposedly unmasked as “Bolshevism of antiquity,” the ND did not opt for atheism or agnosticism, for that would have led it to a materialism similar to that of liberals and Marxists, but dug into the romantic trunk and revived the term “paganism”: A paganism reconstructed somewhat to contemporary tastes, braided with strands of heroic vitalism, sacred sense of nature, religious dimension of the political community, aestheticizing eroticism, “trifunctional” image of social life according to the model discovered by Georges Dumézil in the Indo-European pantheons, elements of “traditional thought” (Evola, Guénon) and of the “philosophia perennis” (Huxley), models of interpretation of the sacred extracted from Rudolf Otto and Mircea Eliade, and so on…

The mixture was of the most heteroclite, but it was very suggestive. At a time when either the flatter materialism or the neo-spiritualist sects were spreading everywhere, the paganism of the ND offered a beautiful and attractive panorama. Above all, it offered a way of understanding the sacred at a time when churches were becoming empty. De Benoist expounded this paganism in Comment peut-on être paien (How to be a Pagan) and then underwent successive reformulations. The most brilliant is undoubtedly the dialogue between De Benoist and the Catholic thinker Thomas Molnar (another of the Catholics who supported De Benoist in the founding years of the ND), in the volume, L’éclipse du sacré (The Eclipse of the Sacred), which is a fascinating exploration of the universe of the spirit. Of course, the pagan option of the ND allowed for the shaping of an alternative spirituality from positions that were not egalitarian, but differentialist; not individualistic, but communitarian; not universalist, but identitarian.

The problem was that, in reality, this paganism had no real correlation with European antiquity, but was an intellectual construction twenty centuries later. It would be more appropriate to speak of a “neo-paganism.” It was a matter of updating pre-Christian ways of thinking the spiritual in relation to the social. The ND does not “resurrect” the ancient gods; that of “resurrection” is a widespread argument among critics of the ND, but it does not fit the reality of the texts. What the ND does is to recover the pre-Christian mental structure, which is interpreted as an essentially pluralistic and diversifying structure, and to oppose it to the Christian mental structure, which would be supposedly monistic and homogenizing. The context of this recovery was not of a strictly religious nature (replacing some gods with others), but of identity: to recover a specifically European way of thinking. In this context, the aesthetic rehabilitation of pagan forms—from the Greek column to the Celtic interlace—does not have a theological function, but a symbolic one; it is a matter of manifesting the validity of a deep-rooted, specifically European cultural world.

And in this rehabilitated neo-paganism, where was the sacred, religion, properly speaking? It was left out of the game—and this is the big question. Generally speaking, the paganism of the “de Benoist strand” was enclosed in a “sociological” interpretation. Now, we can talk about the gods, but, if we do not believe in their real existence, are we not in an empty discourse? To interpret the plurality of gods as a poetic representation of the plurality of social, natural and human forces is a valid option; but, ultimately, it is no more scientific than to represent all these things not with gods, but with saints or constellations. Why resort to the pagan pantheon? Out of loyalty to the European tradition? Fine, but why should the pagan pantheon be more “traditional” than the Christian one, because it is autochthonous, uncontaminated by extra-European elements? But are not St. George, St. Benedict or St. Bernard, the processions of the Virgin or the spirit of the Crusade, or the German and Spanish mystics exclusively European?

A similar contradictory atmosphere appears in one of the “aestheticizing” features with which the ND wrapped its pagan strand, namely that of the “liberation of customs.” In the context of the 1970s and 1980s, the theme of “pagan liberation” enjoyed a certain social presentability—as opposed to the caricature of a Christianity drawn with the thick strokes of sexual repression, intellectual narrowness and social egalitarianism, the pagan imaginary represented a lost paradise of freedom of customs, vital joy, intellectual pluralism and political health. Undoubtedly, the second picture is much more sympathetic than the first. The problem is that the portrait is arbitrary.

In the history of pre-Christian Europe, we find as many examples of intellectual pluralism as of fanatical closed-mindedness, of political health as of generalized corruption, of vital joy as of dark superstitious terror, of freedom of customs as of moral austerity. Conversely, in the history of Christian Europe there is no lack (on the contrary, there are plenty) of examples of relaxed social customs, existential joviality, bold thinking and healthy political institutions; especially if we make the prescriptive differences between the colorful Catholic Mediterranean universe and the gloomy Anglo-Saxon Protestant world, for example. All this without going into other considerations, such as, for example, the usual conjunction of political decadence and intellectual splendor, so frequent in history; or, to stick to religious matters, the wide gap that exists in pagan Europe between “religious” thought (where it is possible to speak of such) and popular religiosity. Thus, the radical distinction between the luminous pagan world and the gloomy Christian world does not cease to be somewhat arbitrary. This distinction comes, in reality, from an inverted intellectual process: two series of values are chosen—one positive, the other negative—and are projected a posteriori on referents that contain a lot of imaginary, fantastic and mental construction. The resulting picture is attractive, as usually happens with imaginary creations; but it cannot seriously support a philosophical interpretation of the History of Religions.

On the other hand, and concerning the specific point of freedom of morals, in the discourse of the ND a not minor contradiction arises—even accepting that the pagan moral world is a “liberated” world (which in itself is debatable), how does one combine the defense of freedom of morals with the critique of the narcissistic hedonism of modern Western civilization? For one of the essential characteristics of modern Western civilization is hedonism, the existence of the masses for mass pleasure; and the ND, quite rightly, rebukes that hedonism with such endorsements as Christopher Lasch’s critique of the “Narcissus complex.” The current hedonism is a direct consequence of individualism, of that way of living—typically modern—which consists in the fact that the individual tends to cut all links with everything around him in order to privilege the narrow interest of his own “I”, something that the ND rightly criticizes. What does this “freedom of customs” have to do with that other elementary religiosity of sex as it occurs in primitive societies? Strictly nothing, one thing and the other correspond to different mental worlds. This should warn us against choosing certain contemporary values and projecting them onto past worlds; this will inevitably be an exercise in decontextualization, i.e., a lax construction.

It is not possible to defend freedom of customs and at the same time reprove the narcissistic hedonism of Western civilization. In the same way that it is not possible to defend the importance of one’s own cultural tradition, the validity of the sacred and the European historical identity, and at the same time to proscribe Christianity, which in its Catholic form—more than in its Protestant form—is the form in which the sacred has traditionally manifested itself in the sphere of European identity.

But perhaps the point from which the inadequacy of the ND critique of Christianity is most clearly perceived is precisely that of the charges of the accusation; that is, all those themes in which the anti-Christian discourse of the ND believed it saw the origin of modern evil. For it turns out that those themes—individualism, egalitarianism, universalism—are not exclusively Christian. The idea of the immortal soul breathed into all men appears, in Europe, at least with Pythagoras, that is, in the 6th century BC. Likewise, the idea that there is an inherent quality in the individual, something that singles him out and makes him unique, appears in the Greco-Latin sphere and finds a concrete expression in the concept of “person” developed by the Roman jurists. Finally, the concept of the universal appears, in philosophy, with Plato’s theory of ideas, and in politics, with the praxis of the Roman Empire. Thus, those three “ideologemes” of modernity—egalitarianism, individualism, universalism—which in Christian doctrine appeared in an ambiguous and contradictory manner, appear with much greater clarity in the pagan cultural tradition. Nietzsche himself, in The Birth of Tragedy, did not so much point against the Nazarene as against Socrates, inventor of the “spirit itself.”

And even more, within the presumably pagan arsenal that the ND recovers, there are essential elements that, nevertheless, belong equally to the Christian order. This is the case, for example, of the trifunctional scheme that Dumézil interpreted—brilliantly—in the Indo-European pantheons and that structured at the same time the world of the gods and the world of men around three functions: the first, that of wisdom, identified with priesthood, kingship and law; the second, that of vital force, identified with war, the nobility of arms; the third, that of production and sustenance, identified with agriculture, work, craftsmanship. It is true that the pagan gods of the Indo-European peoples can be structured in these three families, and it is true that the scheme is likewise reproduced in the social order of ancient Europe. It is, moreover, the model that, as Plato tells us, Socrates imagined: a society of human aspect where there is a head (first function, ruling), a chest (second function, warrior) and a belly (third function, producer). Now, this is exactly the same model that Catholic Europe will maintain for a millennium and a half—with the degenerations we know—from the fall of the Roman Empire to the French Revolution, on the basis of the three medieval orders: oratores, bellatores, laboratories. Where is the Christian subversion?

Theoretical Ellipses

These things are so obvious that, evidently, they could not escape the attention of those who worked in the field. Whether one held a strictly religious view, that is, of belief in supernatural realities, or whether one defined the sacred in philosophical-sociological terms, that is, as a way of representing a worldview, the pagan option was no less problematic than the Christian one. From this point on, the discourse of the ND began to describe theoretical ellipses that did not fail to raise interesting reflections, but which inevitably returned—by definition—to the starting point. We can mention some of them by way of complementary illustration.

A first ellipse was the scientific one: the reflections derived from subatomic physics—Heisenberg, Lupasco, Nicolescu, etc.—led to the identification of a sort of underlying order in the realm of matter and, therefore, to the perception of a sacred imprint in the world. Anne Jobert expounded this in her study, Le retour d’Hermès : de la science au sacré (The Return of Hermes: From Science to the Sacred). The question was of enormous interest and was linked to one of the great contemporary debates. It could have meant a way of thinking the sacred in intimate relation with the scientific interpretation of the world. However, no one in the ND—apart from Jobert herself—went further along that line. On the contrary, from the 1990s onwards, the inspiration of “spiritualist physics” disappeared and was replaced by a pure neo-Darwinism, a position represented in particular by Charles Champetier. Where the strand “scientific spirituality” was followed, so to speak, was no longer in the French ND, but in Italy (Nuova Destra Italiana), in particular with the work of Roberto Fondi, on organicism.

Another example of theoretical ellipsis was the opening of the ND—especially through the journal Krisis—towards Christian personalism, with an interesting debate between Alain de Benoist and Jean-Marie Domenach, Mounier’s intellectual executor—since the ND had marked a position contrary to modern individualism and mass society, nothing more natural than to converge with a current of thought that had arrived at the same position from a different starting point. But Christian personalism is, by definition, Christian, and its concept of the person is built on the conviction that all individuals possess a transcendent value that is identified with the soul. Perhaps the ND could have taken its cue from this convergence with Christian personalism to recover the Roman concept of “person,” but there was no such convergence. On the other hand, around the same time, Nouvelle École published a long work by Alain de Benoist on (against) Jesus of Nazareth, which in reality was nothing more than a recovery of the old and hostile Jewish literature against the “false Messiah.” Another road closed.

More ellipses? The philosophical one, for example. The ND emerged from the Nietzsche impasse by incorporating Heidegger into its theoretical stock. The Heideggerian critique of Western metaphysics—a critique to which the concept of the “will to power” does not escape—could be interpreted as a definitive diagnosis of the modern disease. And the Heideggerian imperative to “think what the Greeks thought, but in an even more Greek way” could well be interpreted as a demand for a return to the pagan origin. Now, Heidegger’s own interpretation, with its denunciation of the “forgetfulness of Being,” carries an implicit longing not only for the sacred as “enchantment of the world” (Weber), but also for the divine as an active presence in the realm of matter. This explains that famous statement to Der Spiegel: “Only a God can save us.”

Personally—and may I be excused for summarily dismissing a matter so subject to discussion—I believe that Heidegger tried throughout his life to speak of God, obstinately trying to do so without pronouncing the word God and personifying Him in the concept Being, and his last breath was precisely to say that only a God can save us. It is a similar path to that of another of the key thinkers for the ND, Ernst Jünger, with the relevant exception that he discovered the divine imprint with less makeup, invoked it frequently and ended up, as is known, converting to Catholicism, despite being from a Protestant background. The discourse of the ND, in this sense, returns once again to its own starting point: it does not hurry the reasoning, it stops before the necessary logical leap—thinking the sacred as divine presence—and goes back to the same place where the first question had been posed.

It is not difficult to suspect that these elliptical developments obey an objection of principle, a mental reservation, a prejudice of departure: the line of thought developed by Alain de Benoist, so fruitful in other fields, so ready to venture into diverse territories—so capable, for example, of reaching convergences with a certain intellectual left on the critique of the market or on the praise of the idea of community—nevertheless suffers from a clear taboo on religious matters, a kind of insurmountable inhibition. This taboo, this inhibition, is no mystery, but is a substantial part of modern thought. It is simply the impossibility of thinking of God—or, more generically, the divinity—as Someone endowed with real existence. The ND shares this modern prejudice that consists in discarding the hypothesis of God. It is interesting—the ND, which has criticized so much—and so rightly—the Western model of thought, both scholastic and Cartesian, because it desacralizes the world, because it separates the sacred from nature, nevertheless remains subject to that same model by implicitly discarding the hypothesis of God.

This is not a new phenomenon in the history of ideas. Let us recall the scene: University of Tübingen, 1791; three young students named Hegel, Hölderlin and Schelling attempt to enlighten a philosophy so spiritual as to satisfy people of a religious temperament and, at the same time, a religion so exact and systematized as to satisfy people of a philosophical spirit. The result was philosophically estimable, but, from the religious point of view, it was an entirely artificial construction. For religion necessarily demands the participation of mystery, and to create mystery is not something within the reach of men.

But let us stop here, because it would take us too far. We can limit ourselves to stating the ultimate conclusion of this journey through the religious problematic of the ND, namely—we are facing a dead end. Consequently, it is valid to think that the itinerary was badly traced from the beginning.

In the end, work in the field of the History of Ideas always runs the risk of Ideas emancipating themselves from History, so that we end up with formally estimable constructions, but with no real basis. To put it in a few words: if Christianity were really the seed of the modern world—materialist, egalitarian, etc.—it would be necessary to explain how it was possible for Christianity to reign in the West for a millennium and a half without the emergence of the modern order, and even more, it would be necessary to explain why the first providence of the modern order, wherever it arose, was always and unfailingly to proclaim the death of Christianity. Since it is impossible to explain these two things and maintain logical coherence, there is no choice but to think that the analysis of the ND, on this point, is wrong.

This does not prevent us from thinking that Christianity faces a major challenge, and this concerns Catholicism more specifically, because it is the last great reservoir of sacredness in the West. This challenge does not concern theological discourse, which is impregnable by its very nature, but the philosophical discourse with which the Church presents itself in the world of secularization; that is, in that world where the sacred has been confined to a corner and religiosity is an individual choice like any other. Before the explosion of modernity, religion, Western metaphysics and political order tended to be one and the same thing; on the contrary, after the revolutions, the Enlightenment—and its glories and its ruins—the triumph of technical civilization and the great wars of the twentieth century, world order goes one way, culture goes another and religion seeks a place in the sun. If in the past Western metaphysics was inseparable from ecclesiastical cathedrae, it is obvious that it has long since ceased to be so; if in the past the order of the world was inseparable from the authority of the Papacy, it is equally obvious that today there is nothing of the sort; if in the past culture and the feeling of the sacred could maintain a relationship of close intimacy, today it is also obvious, finally, that this bond has been broken.

In this regard, Rome has come a long way since the 19th century, and Christian thought (or, if one prefers, the thought of Christians who have dedicated themselves to thinking) has not failed to provide very interesting insights. But the major forces guiding the culture of our time—criticism, suspicion, doubt, uncertainty, fragmentation, nihilism—have shaken the Church as they have everything else, creeds and certainties, ideologies and philosophies. If it was difficult to make faith survive in the world of scientific positivism, as was the case in the 19th century, the task seems even more difficult in the world of technical nihilism, which is the one in which we live. Thus, Christian thought seems fundamentally problematic in matters such as man’s relationship with nature, the presence of religion in the political and social order or the validity of tradition in a culture of permanent change, to give just three examples of daily debates.

However, in this atmosphere of aftermath, where everything seems to have been pushed to its ultimate extreme, as if dragged by the hair by a demonic force, this is precisely where the fundamental questions come back to the fore. No one wonders what is on the other side of the river until their feet touch the shore; today we are already soaked to the waist. This, in any case, is a matter for another reflection. The only thing to be regretted, to return to the thread of our theme, is that the ND or the French New Right, due to its own inhibitions, is no longer in a position to attend this event.

José Javier Esparza, Soanish historian, journalist, writer, has published around thirty books about the history of Spain. He currently directs and presents the political debate program “El gato al agua,” the dean of its genre in Spanish audiovisual work. (Thank you to Arnaud Imatz for all his wonderful help).