During the bloody Five-Day War in Tskhinvali there was an incident: a Georgian grandfather, a peasant, terrified, shouted to a Russian soldier, “Don’t shoot, son. Maybe I am your father!”

Eyewitnesses recounted that there was fear in the elderly man’s eyes, not for himself, but for the biblical tragedy of the son killing his father. Perhaps, remembering the decades of carrying apples in southern Russia, and recalling some vicious connection from his youth with a local woman, suspecting that he had a son by her, he impulsively shouted these words. Otherwise, he would hardly have dared to utter them at the risk of his own life, in case the soldier’s possible interpretation of this exclamation was mockery.

This incident revealed to me even then the great depth and breadth of the reasons for the behavior of people in war, which I call Genesis within the Logos of war.

I experienced it myself several times, when I was undone by soldiers on April 9, 1989, during the fratricidal civil war in Tbilisi, when my parents, sister and I lay on the ground for eight hours under bullets spraying our house, and when our house was burned down, and when we lived in Tskhineti together with thousands of exhausted and humiliated people. And in 2008, when I had to evacuate my family from Georgia to Azerbaijan on the night of August 12 to avoid being forced to cooperate with the Russian military in case the maniacal Saakashvili regime was overthrown.

Throughout this bitter civilian experience, and I think I am not the only one, a particular residue accumulated that yet influences my view of the real; and as I understand the causes of wars, the rules of their conduct and the reasons for their end.

I think that sometimes this viewpoint deviates so much from everything that is pronounced and explained in today’s society that it is incomprehensible to most readers of these words, which I certainly regret.

However, in spite of my sincere and deep desire not to offend anyone, I cannot refrain from expressing it, because I am filled with emptiness listening to the possible explanations of why the Big Russians and the Little Russians, or whatever they are called today—Russians and Ukrainians, are at war.

The language itself, to which I must now turn, is in strong dissonance with the preceding paragraphs, because of its poetic-philosophical content, which I have neither the energy nor the inclination to enunciate in the modern lingua franca—perhaps because of the continuing and difficult process of healing from two simultaneous terminal illnesses, which strangely affected me last year, immediately after my unwelcome entry into Georgian politics.

In Postmodernity, which is being consumed on the ashes of Modernity, the object of man’s main robbery is a dignified death. Having eviscerated humanity, the modern and postmodern have surprisingly robbed it of the most important thing—the very Meaning of Life.

By transforming a perverted version of this very Sense of Life into such pathetic interpretations as longevity and the quality of goods and services consumed, the urban-centric Matriarchy has shredded the remnants of the rural-centric Patriarchy, which has died out over the past four centuries at the epicenter of humanity’s gangrene, in Western civilization, and has begun to diverge in more or less concentric circles (depending on the quality of resistance to this decay) from different cultures.

Probably no culture can boast of being completely unscathed by this rot, and each tries to resist it as best it can. Russians (big, small or white) know how to fight back. Probably better than anyone else. It is nice when they call themselves the most peaceful people in the world and explain that they have most of the world by accident or coincidence; but the fact that war is their main element, every non-Russian knows or intuits.

By confronting the entropy of the Modern and Postmodern by means of war, the Russians, having joined the battle between their two hypostases; the Great Russian and the Little Russian, have created a salvific dome around themselves, within which they are born for the Postmodern, in mutual murder.

The fact that Ukrainians are also Russians can be seen not only by the quality of their opposition to the Velikoross, i.e., the Russians, but precisely by this confrontation with the sky closed to them by planes in the open field. Some Taliban in the mountains of Tora-Bora, or Caucasians in the Caucasus, can fight with the sky closed to them, taking cover in the mountains, but in the open field only the Russians can do so.

By the way, once some mercenaries around the world are in these conditions, all it takes is a missile from that same closed sky for them to be reduced to ashes, whimpering in video selfies. At the same time, this is not an ethno-genetic phenomenon. Other ethnic groups also fight on the side of the Velikorossi and Little-Reds; but provided they belong to the Logos of Russian civilization.

Here, however, the standing and impatient trampling of the Belarusians, deprived of the opportunity to achieve a dignified death, looks especially cute next to each other.

Some, stupefied by Modernity, will consider it nonsense that consumers are the same everywhere, that no one wants to fight, and that some autarchs and representatives of the elite are at war here. Here the autarky and the elite are finally forced to obey the deep voice of the Logos of the People, who, unknowingly, while munching sauerkraut and drinking beer near a bar, are eager not to become like the Western consumer, androgynous and sexless, and therefore not only want, but with a ringing voice call for a war, for lack of a better one, even with itself.

“But this is the interpretation of cannibalism!” someone will say, offended. Yes, when the other is taken away, it is also a form of taking away necessary flesh and blood.

A particular and concrete proof of this mutual desire for renewal of Being within the Logos of war is the countless opportunities for avoidance by Big and Little Russia in the past years, on which both sides wanted to (and have) spit.

The brutal instigation of the Anglo-Saxons does not count in this case, the Kartvelians know as much about it as the Russians do, but about the real causes of the hitherto unheard-of Russo-Kartvelian war we shall speak another time.

Here, we are talking about something else, about the most interesting process of resolving the collective unconscious within the essentially united Logos of the Russians—the mutual self, or combustion to infer the end of the stinking Western Postmodern; and from its ashes rise together as a united Russian fusion for the Postmodern.

For Anglo-Saxons, war is a cost, and a cost of everything: money, lives, armaments, economies. For Russians, war is the homeland, because no one else in the world has that expression.

While weakening the Russians in peacetime, the West, once in a hundred years, because of its greed for matter, cannot resist the temptation to take the peace-weakened Russians and go to war. And it is inevitably repulsed by the Russians, who are reborn in war.

The West becomes more cunning, from century to century; and today it has deceived even itself: realizing the invincibility of the Russians for a long-time following World War II, it finished them off with the “cold war” and almost completely stuffed them with the Philistine world after its end.

But again, it could not resist and decided to try again to finish them off, now with infighting, thinking to at least “save” its own blood, if not other expenses. But that is all the Russians needed; they were fighting feuds and, invisible to the West, they began to revive each other.

Only Kissinger, who seems to have seen something in his 99 years, suggested what I understood as a cry of desperation—take the main weapon of reinforcement, war, out of the hands of the Russians. Do anything, divide the Ukrainian state, anything; but stop the elements, which again we decided would weaken them (and again we forgot that it only strengthened them).

The manifestations of this strengthening of the Russians in war are manifold: the flight from both capitals of Russ of consumers and representatives of the “fifth column;” the renewal of military arsenals; the liberation of both systems from the Fed’s fiefdoms; the reduction of sin in these lands during the war; the increase of righteousness on both sides as a result of the great suffering; the complete denudation and shaming of the Western scaremongers, so prominently described in recent decades; and a complete reboot of the mirage of the matrix as such—an undoing of the game; a true Great Reset, such as none of the “Schwabs” ever dreamed of. In short, a complete disaster for the West.

Compared to this, the mutual and sincere hatred of the warring parties, as well as the sincere patriotism with which they conduct this war on both sides, this too is nothing. Because all the space that the Russians inhabit is being destroyed by the slime of Postmodernity, which smells like a corpse.

We do not know what will emerge in place of the fire. But whatever it will be, it will be the antithesis of Postmodernity, which in its chaotic and illogical nature has apparently convinced itself that no other way is possible.

Having achieved extreme fragmentation; or, according to Plotinus, plurality, Postmodernity, in all its anti-postmodern forms, has convinced itself of the impossibility of reuniting in the One: and here too it has made a fatal mistake. In fact, it repeated its own mistake during the thrashing of the 14,000 infants in Bethlehem, deciding, upon hearing Rachel’s lament, that she did not really want to be consoled.

And finally let us say the main thing in the coming collapse of the Modern and Postmodern: the re-education of the young. The inevitable current kidnapping of youth by the pacifist scream of Postmodernism, which is being murdered in Little Russia, will in time be replaced by the inevitable realization of the falsity of this scream. And this change will take place not only in the space of the Russians, but all over the world. It is then that the Postmodern will find itself in trouble. It will remain, of course, but now it will have to take refuge in the margins of geography, forget about hegemony and begin the process of self-improvement, in which it will hardly succeed.

Levan Vasadze is a well-known Georgian businessman who is active on the political scene of his country. [Translated kindly provided by Costantino Ceoldo, and this article appears courtesy of Geopolitika.]

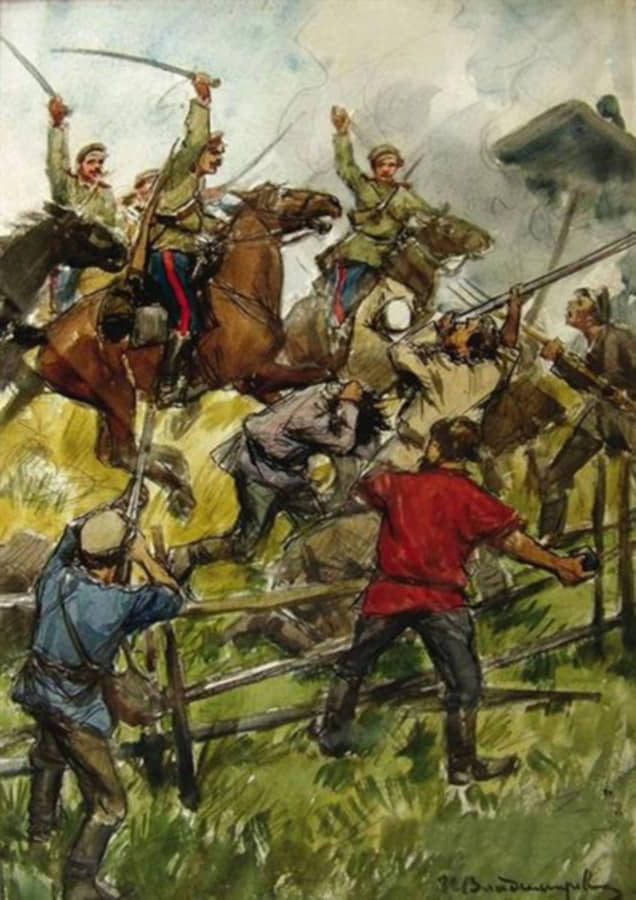

Featured: Study, “Revolt of the peasants on the estate of Prince Shahovskoy,” by Ivan Vladimirov; painted ca. 1917-1922.