It is a great honor to bring to you this excerpt from Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, a book that must be widely read, because it brings clarity, moderation, scholarly depth and much-needed insight to a topic heaped over by hurt feelings (largely contrived) of those who have benefited most from colonialism. The book meticulously shows that the various narratives against the British Empire are exaggerated at best, since the factually measurable achievements of Empire total a great moral good—it was a Golden Age. This book will no doubt enrage those who have made a career of knee-jerk, anti-colonial pronouncements… but, then, truth is often bitter and thus decried.

Professor Biggar is emeritus regius professor of moral and pastoral theology at the University of Oxford, and his work is marked by nuance, perspicacity, and brilliance.

As some may know, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning was “canceled” by its first publisher which could not help but virtue-signal. Fortunately, courage yet remains among better publishers (William Collins), and the book is now out in print.

Please consider supporting Professor Biggar’s pivotal work by purchasing a copy of this book and by spreading the word.

What follows is an extract from the “Introduction” to Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, published by William Collins.

It was early December 2017 and my wife and I were at Heathrow airport, waiting to board a flight to Germany. Just before setting off for the departure gate, I checked my email one last time. My attention sharpened when I saw a message in my inbox from the University of Oxford’s public affairs directorate. I clicked on it. What I found was notification that my “Ethics and Empire” project had become the target of an online denunciation by a group of students, followed by reassurance from the university that it had risen to defend my right to run such a thing. So began a public row that raged for the best part of a month. Four days after I flew, the eminent imperial historian who had conceived the project with me abruptly resigned. Within a week of the first online denunciation, two further ones appeared, this time manned by professional academics, the first comprising 58 colleagues at Oxford, the second, about 200 academics from around the world. For over a fortnight, my name was in the press every day.

What had I done to deserve all this unexpected attention? Three things. In late 2015 and early 2016 I had offered a qualified defence of the late 19th-century imperialist Cecil Rhodes during the first Rhodes Must Fall campaign in Oxford. Then, second, in November 2017, I published a column in The Times, in which I referred approvingly to the American academic Bruce Gilley’s controversial article “The Case for Colonialism” and argued that we British have reason to feel pride as well as shame about our imperial past. Note: pride, as well as shame. And third, a few days later I finally got around to publishing an online account of the Ethics and Empire project, whose first conference had been held the previous July.

Thus did I stumble, blindly, into the “imperial history wars”. Had I been a professional historian, I would have known what to expect, but being a mere ethicist, I did not. Still, naivety has its advantages, bringing fresh eyes to see sharply what weary ones have learnt to live with. One surprising thing I have seen is that many of my critics are really not interested in the complicated, morally ambiguous truth about the past. For example, in the autumn of 2015 some students began to agitate to have an obscure statue of Cecil Rhodes removed from its plinth overlooking Oxford’s High Street. The case against Rhodes was that he was South Africa’s equivalent of Hitler, and the supporting evidence was encapsulated in this damning quotation: “I prefer land to ners . . . the natives are like children. They are just emerging from barbarism . . . one should kill as many ners as possible.” However, initial research discovered that the Rhodes Must Fall campaigners had lifted this quotation verbatim from a book review by Adekeye Adebajo, a former Rhodes scholar who is now director of the Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation at the University of Johannesburg. Further digging revealed that the “quotation” was, in fact, made up from three different elements drawn from three different sources. The first had been lifted from a novel. The other two had been misleadingly torn out of their proper contexts. And part of the third appears to have been made up.

There is no doubt the real Rhodes was a moral mixture, but he was no Hitler. Far from being racist, he showed consistent sympathy for individual black Africans throughout his life. And in an 1894 speech he made plain his view: “I do not believe that they are different from ourselves.” Nor did he attempt genocide against the southern African Ndebele people in 1896—as might be suggested by the fact that the Ndebele tended his grave from 1902 for decades. And he had nothing at all to do with General Kitchener’s “concentration camps” during the Second Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902, which themselves had nothing morally in common with Auschwitz. Moreover, Rhodes did support a franchise in Cape Colony that gave black Africans the vote on the same terms as whites; he helped finance a black African newspaper; and he established his famous scholarship scheme, which was explicitly colour-blind and whose first black (American) beneficiary was selected within five years of his death.

However, none of these historical details seemed to matter to the student activists baying for Rhodes’s downfall, or to the professional academics who supported them. Since I published my view of Rhodes—complete with evidence and argument—in March 2016, no one has offered any critical response at all. Notwithstanding that, when the Rhodes Must Fall campaign revived four years later in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, the same old false allegations revived with it, utterly unchastened.

This unscrupulous indifference to historical truth indicates that the controversy over empire is not really a controversy about history at all. It is about the present, not the past. A remarkable feature of the contemporary controversy about empire is that it shows no interest at all in any of the non-European empires, past or present. European empires are its sole concern, and of these, above all others, the English—or, as it became after the Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707, the British—one.

The reason for this focus is that the real target of today’s anti-imperialists or anti-colonialists is the West or, more precisely, the Anglo-American liberal world order that has prevailed since 1945. This order is supposed to be responsible for the economic and political woes of what used to be called the “Developing World” and now answers to the name “Global South”. Allegedly, it continues to express the characteristic “white supremacism” and “racism” of the old European empires, displaying arrogant, ignorant disdain for non-western cultures, thereby humiliating non-white peoples. And it presumes to impose alien values and to justify military interference.

The anti-colonialists are a disparate bunch. They include academic “post-colonialists”, whose bible is Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) and who tend to inhabit university departments of literature rather than those of history. But academic “post-colonialism” is not just of academic importance. It is politically important, too, in so far as its world view is absorbed by student citizens and moves them to repudiate the dominance of the West.

Thus, academic post-colonialism is an ally—no doubt inadvertent—of Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia and the Chinese Communist Party, which are determined to expand their own (respectively) authoritarian and totalitarian power at the expense of the West.

In effect, if not by intent, they are supported by the West’s own hard left, whose British branch would have Britain withdraw from Nato, surrender its nuclear weapons, renounce global policing and retire to freeride on the moral high ground alongside neutral Switzerland. Thinking along the same utopian lines, some Scottish nationalists equate Britain with empire, and empire with evil, and see the secession of Scotland from the Anglo-Scottish Union and the consequent break-up of the United Kingdom as an act of national repentance and redemption. Meanwhile, with their eyes glued to more domestic concerns, self-appointed spokespeople for non-white minorities claim that systemic racism continues to be nourished by a persistent colonial mentality, and so clamour for the “decolonisation” of public statuary and university reading lists. In order to undermine these oppressive international and national orders, the anticolonialists have to undermine faith in them.

One important way of corroding faith in the West is to denigrate its record, a major part of which is the history of European empires. And of all those empires, the primary target is the British one, which was by far the largest and gave birth to the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. This is why the anti-colonialists have focused on slavery, presenting it as the West’s dirty secret, which epitomises its essential, oppressive, racist white supremacism. This, they claim, is who we really are. This is what we must repent of.

This all makes good sense politically—provided that the end justifies any means and you have no scruples about telling the truth. Historically, however, it does not make good sense at all. As with Cecil Rhodes, so with the British Empire in general, the whole truth is morally complicated and ambiguous. Even the history of British involvement in slavery had a virtuous ending, albeit one that the anti-colonialists are determined we should overlook. After a century and a half of transporting slaves to the West Indies and the American colonies, the British abolished both the trade and the institution within the empire in the early 1800s. They then spent the subsequent century and a half exercising their imperial power in deploying the Royal Navy to stop slave ships crossing the Atlantic and Indian oceans, and in suppressing the Arab slave trade across Africa.

There is, therefore, a more historically accurate, fairer, more positive story to be told about the British Empire than the anti-colonialists want us to hear. And the importance of that story is not just past but present, not just historical but political. What is at stake is not merely the pedantic truth about yesterday, but the self-perception and self-confidence of the British today—together with Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders—and the way they conduct themselves in the world tomorrow. What is also at stake, therefore, is the very integrity of the United Kingdom and the security of the West.

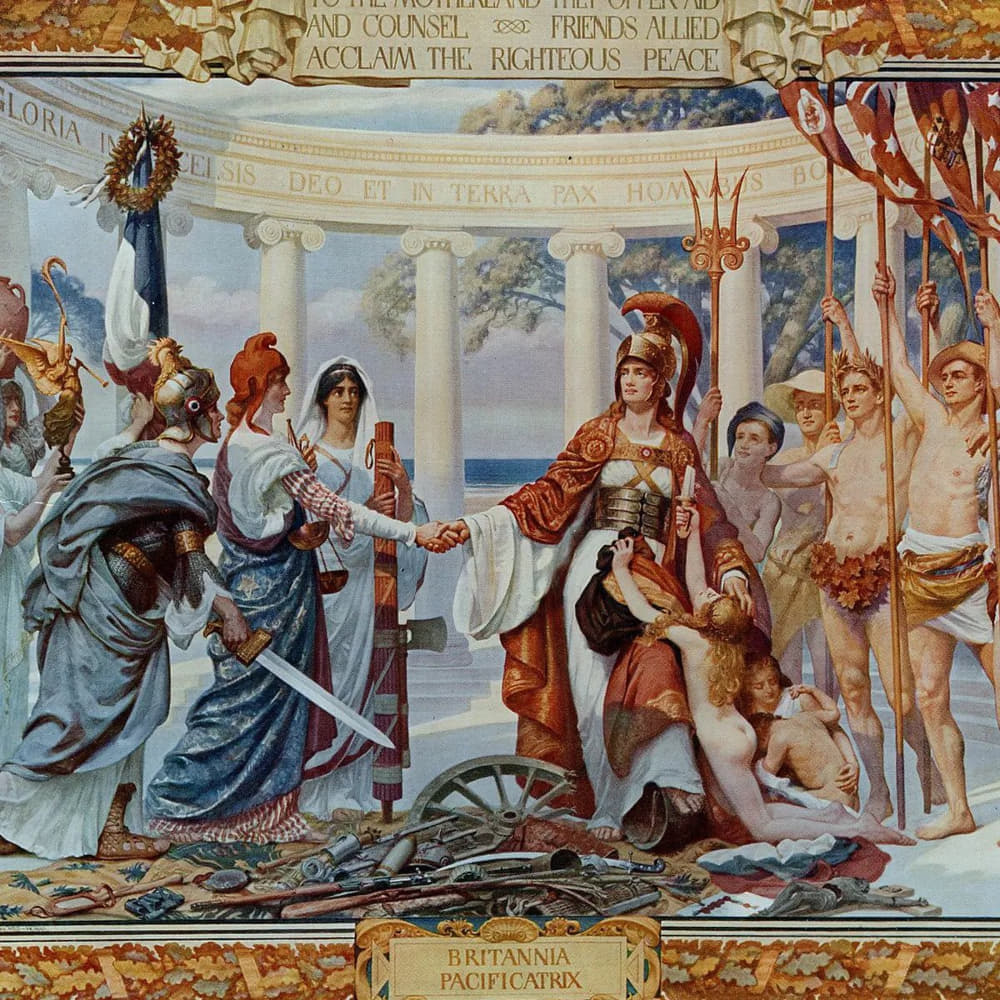

Featured: Britannia pacificatrix, mural by Sigismund Goetze; painted ca. 1914-1921.