The condemnation of abortion by followers of Christ is not new. From the earliest days of Christianity, it has been considered a sin and preached against. Although the truth of this teaching has not changed, some seem to want to redefine both truth and sin. On Women’s Equality Day 2022, U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called restricting abortion “sinful.” Specifically, on August 26, this U.S. representative twisted the idea of sin, stating, “The fact that this is such an assault on women of color and women [in] lower income families is just sinful. It’s wrong that they would be able to say to women what they think women should be doing with their lives and their bodies. But it’s sinful, the injustice of it all.” Pelosi’s idea of sin regarding abortion is the opposite of Church teaching. Her postmodern thinking has made her believe, or present as her belief, that rather than abortion being sinful, the restriction of it is “sinful.”

We will look at what the early church fathers had to say regarding the issue of abortion. For the record, this author has looked, but could not find, any church father that agreed with the U.S. Speaker Pelosi. In fact, every church father that addressed the issue roundly condemned it.

The Jews in the ancient world forbade abortion. The Jewish historian Josephus described the Mosaic law with respect to abortion. In his work Against Apion, Book 2, written circa 80 AD, he stated: “The law, moreover, enjoins us to bring up all our offspring, and forbids women to cause abortion of what is begotten, or to destroy it afterward; and if any woman appears to have done so, she will be a murderer of her child, by destroying a living creature, and diminishing humankind.” Christianity, rooted in the Mosaic law to which Josephus referred, did not change this understanding of the fetus as a living child, and of the deliberate destruction of it as murder.

In ancient pagan Rome, abortion was legal. Some people at the time thought that the soul was introduced into the body after the birth of a child. The church father Tertullian (c. 160 – c. 220 AD) refuted this idea. As part of his refutation, he described in chilling detail the process of the abortion procedure, which does not seem to have changed much in two thousand years. In chapter 25 of his work A Treatise on the Soul, he writes:

“Accordingly, among surgeons’ tools there is a certain instrument, which is formed with a nicely-adjusted frame for opening the uterus first of all, and keeping it open; it is further furnished with an annular blade, by means of which the limbs within the womb are dissected with anxious but unfaltering care; its last appendage being a blunted and covered hook, wherewith the entire foetus is extracted by a violent delivery. There is also (another instrument in the shape of) a copper needle or spike, by which the actual death is managed in the furtive robbery of life: they give it, from its infanticide function, the name of ἐμβρυοσφάκτης, ‘the slayer of the infant’, which was of course alive.”

Tertullian made it clear the fetus was alive, even if unborn. (For more details on abortion in ancient Rome and the Christians, see here).

One of the earliest Church Fathers who spoke on the topic of abortion was St. Barnabas. Writing between 70 and 100 AD, he exhorted “You shall not slay the child by procuring abortion; nor, again, shall you destroy him after it is born.” St. Barnabas clearly views the fetus as a living human child, and equates abortion with “slaying,” that is, murdering, the child. Notice also that St. Barnabas addresses abortion and infanticide in the same sentence, considering them equivalent sins.

St. Hippolytus, writing around 225 AD, explained in his work Refutation of all Heresies, Book IX, that “Whence women, reputed believers, began to resort to drugs for producing sterility, and to gird themselves round, so to expel what was being conceived on account of their not wishing to have a child either by a slave or by any paltry fellow, for the sake of their family and excessive wealth. Behold, into how great impiety that lawless one has proceeded, by inculcating adultery and murder at the same time!” Clearly, the practice of sidelining one’s religion [“reputed believers”] in order to accommodate [“for the sake of their family and excessive wealth”] or approve of pet sins did not originate recently.

St. John Chrysostom states that abortion is worse than murder. His Homily 24 on Romans, written in the late 300s AD, asked: “Why sow where the ground makes it its care to destroy the fruit? Where there are many efforts at abortion? Where there is murder before the birth? For even the harlot thou dost not let continue a mere harlot, but makest her a murderess also. You see how drunkenness leads to whoredom, whoredom to adultery, adultery to murder; or rather to a something even worse than murder. For I have no name to give it, since it does not take off the thing born, but prevents its being born. Why then do you abuse the gift of God, and fight with His laws, and follow after what is a curse as if a blessing, and make the chamber of procreation a chamber for murder, and arm the woman that was given for childbearing unto slaughter?” His heartfelt preaching against sin arose from certain conviction of the Gospel of life. How striking, and how current it seems, when Chrysostom upbraids those who “follow after a curse as if a blessing.”

Other early church fathers who spoke out against the sin of abortion were St Cyprian of Carthage (c. 210 – 258 AD) in his letter to Cornelius, (number 48, numbered 52 in some sources); St. Basil the Great (329 -379 AD), in his epistle 138; St Jerome (c. 347 – c. 419) in his epistle 22; and St Ambrose (339 – 397 AD), in his work On the Hexaemeron. The practice of abortion is likewise forbidden in the Didache also known as The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles which was written in the first century or at the latest, the first part of the second century.

From the historical record, it is clear that the early church fathers condemned abortion as a sin. To speak otherwise is to confuse reality.

Phillip Cuccia is a retired army officer, who served in armored and cavalry units, and then taught Military History at West Point, before joining the Army attaché corps, and serving in Italy at the U.S. Embassy in Rome. He has a Master’s degree in security studies from Sapienza University in Rome and a Master’s and Ph.D. in Napoleonic Studies from Florida State University. He currently teaches history for Liberty University. He established the Eusebius Society in 2019.

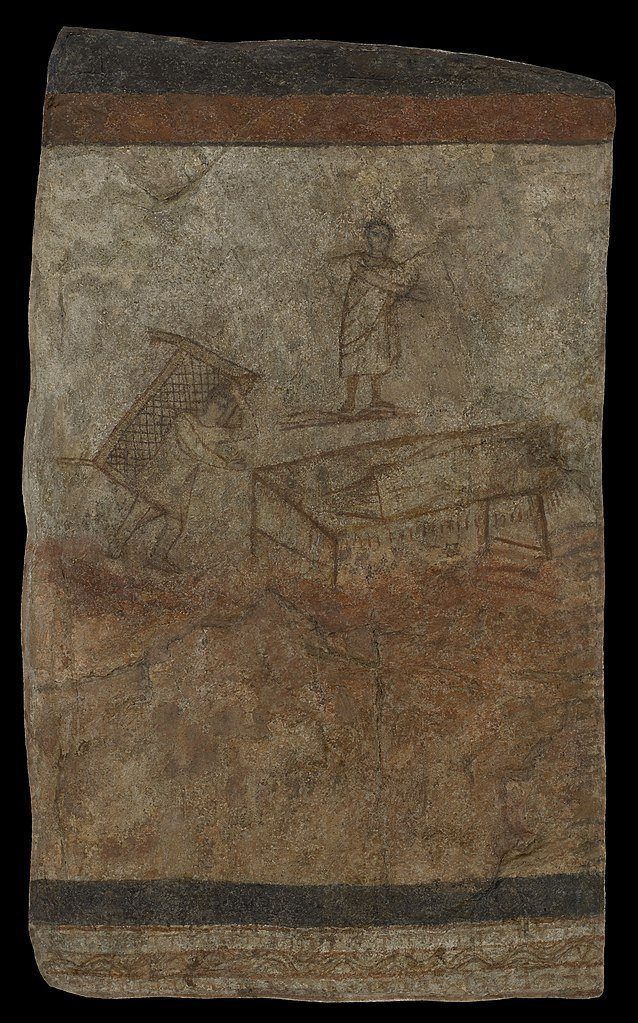

Featured: “Kronos devouring his Children,” by Goya, ca. 1797.