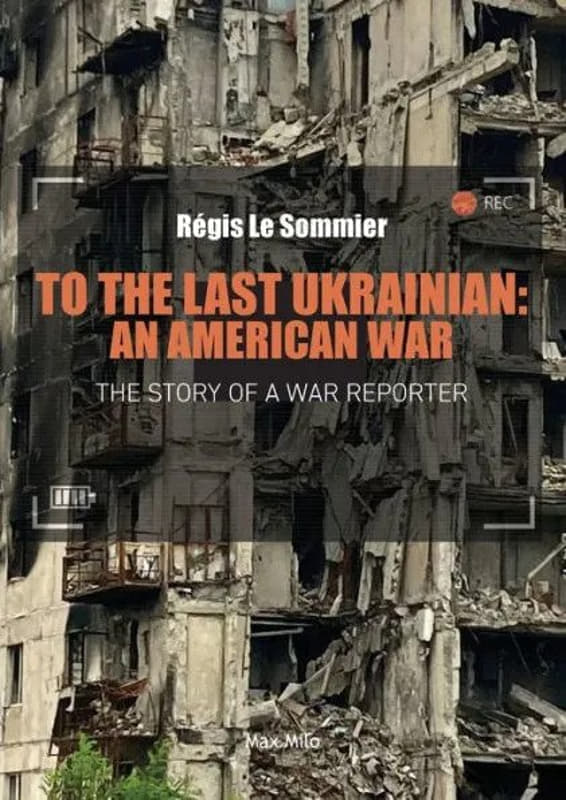

Régis Le Sommier is the author of To the Last Ukrainian: An American War, from which we had the great pleasure of providing an excerpt. We are deeply thankful to his publisher, Max Milo, and to Mr. Le Sommier, to be able to bring you this interview.

The Postil (TP): Could you please tell us a little about yourself for our readers who may not be familiar with your work?

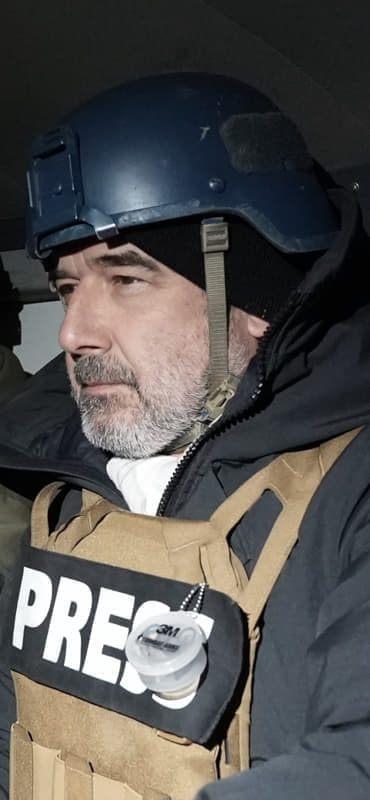

Régis Le Sommier (RS): I am 54 years old. I’ve been a senior reporter for over two decades covering the latest conflicts, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, Mali and Ukraine. I was also the deputy editor of Paris Match magazine and now I am the managing editor of Omerta, an investigation and documentary digital platform.

TP: You have interviewed various American politicians including presidents. Is there a typical style of politics that stands out as being different from politicians in Europe?

RS: They expect to be challenged. Big difference from European leaders who are used to dealing with friendly journalists. They also prepare the interviews much more and don’t ask to read the print copy of the interview before it is published. Another big difference from Europe.

TP: Why is there such strong loyalty to NATO in Europe?

RS: It comes from memories of WWII. Most of Europe had been devastated by the conflict and a lot of Europeans think NATO is their best protection. Eastern European countries, quite logically, see it as a protection from Russia. In the West, it is true also. After all, the biggest success of NATO so far has been to prevent Stalin from invading Western Europe. And it worked quite well up until 1991 and the downfall of USSR. Now in a country like Germany, there are mixed feelings about NATO; but the common opinion is that Germany should stick to it in order not to be pointed out again as the worst evil, in reference to Nazism. France is the most reluctant country to NATO’s influence. Anti-Americanism is strong, both on the Right, with de Gaulle’s legacy, and on the Left, which stayed in Moscow’s sphere for a long time.

TP: Your recent book, To the Last Ukrainian: An American War (which we have excerpted), is a rather grim account of the deep involvement of the United States in the conflict in Ukraine. What compelled you to write this book?

RS: Intuition at first. I have lived six years in the US, between 2003 and 2009, during which I became aware that beyond the fight against radical Islam, a lot of politicians remained committed to fighting Russia, which, I would say, was their true enemy. Ben Laden and Baghdadi being derogative. Second, what I witnessed on the ground, especially the involvement of a US operator for recruitment at the Ukrainian Legion (foreign volunteers). Add to this, the documented story of Maidan and the war in Donbass since 2014.

TP: As you clearly show in your book, the war in Ukraine is an American project. But why did Europe agree to support America against Russia?

RS: Now not only my book says that but this was revealed to the public in a spectacular manner with the Pentagon leaks. Why Europe did that? I don’t know. Because the continent is weak and can only shape short term policies. The French president, however, with his latest remarks on China, surprised me quite a bit. Maybe Emmanuel Macron became convinced of late that the future of France doesn’t necessarily lie in US hands. We’ll see…

TP: There is also the strange rhetoric of armed and financial support of Ukraine, backed by the contradictory claim that such support is not co-belligerence. Why is the West behaving in this way?

RS: Communication. Since, in fact, we are part of this war. Now the public seems to realize that escalation means danger to their comfortable lives. So, support of the war is decreasing.

TP: Why has Europe agreed to participate in Russophobia, even when such hatred is against its best interests?

RS: Because a lot of people have zero memory. Especially young generations who during their studies skip big chunks of history and tend to stick to the present.

TP: Then there is the media. Why does the European (French) media believe that Ukraine is a “good cause?”

RS: I don’t know. A tradition of being respectful of the authorities maybe, driven by our monarchist past? I tend to think that the US press, even biased, is more honest because in the end they stick to facts. When Russians are advancing inside Bakhmut, even the Institute for the Study of War, a neocon think tank, attests that they are. The French press keeps denying it.

TP: You bring a unique perspective—you were embedded with the Ukrainian army (among French volunteers). How would you characterize your experience?

RS: It is always a great thing for a journalist to be able to cover both sides. The war is so inflammatory that you end up almost automatically accused by both sides of being biased. But let me tell you, if both sides hammer you, it means you did your job.

TP: Ukraine and Russia have always been inseparable. But now there is an active drive to separate all traces of Russia from Ukraine. How do you explain this now bitter partition?

RS: This war is intimate. It is a family war. That is why it is so toxic and cruel. And the process to eradicate everything, to deny the other side any human aspect (Russians are Orcs, Ukrainians are Nazis) comes with this deep family feud.

TP: How deep is the neo-Nazi influence in Ukraine and in the Ukrainian military?

RS: It exists at various degrees, especially amongst the elite Ukrainian military. What struck me the most is Bandera’s legacy in Ukrainian countryside. Almost every village, especially in the West, has its Bandera memorial or flags.

TP: Did you meet any military advisors or personnel from France who were helping the Ukrainians?

RS: No, I did not.

TP: Which other countries have the largest number of volunteers fighting on the side of Ukraine? How many have sent military advisors or personnel?

RS: I was told by Russian military fighting Ukrainian “Kraken” battalion near Bakhmut that the biggest group was Polish. That needs to be verified though.

TP: Tell us a little about Max and Sabri, the two volunteers you mention in your book. What has happened to them?

RS: The last info I got was that they are still fighting over there. Greg came back to France.

TP: Do you think this involvement in Ukraine by France stems from the “paradox” that you describe in your book which inhabits the French psyche—anti-Americanism along with an open embrace of American culture?

RS: Double standard, yes.

TP: How do you see America—a hegemon or a friendly, benign influence?

RS: I see it as my second home. I have two children living there and whenever I travel to the US, I blend in, in a split second. Now that doesn’t mean I’m not critical of it. On the international level, it is a country that serves its interests and only that. Democracy, freedom and all of this, are just a way to sugarcoat interventionism. And when things go awry, as they do most of the time, the US leaves ruins behind.

TP: “War is an American specialty,” you say in your book. Could you unpack this for us?

RS: The country has been at war for most of its existence. War and violence are not a US monopoly, but both are definitely a behavior pumped up remarkably by Hollywood. I just spent two weeks in Afghanistan. I was amazed to discover that the Taliban police special units are now dressed up exactly like US operators, the very same ones they were fighting against before. I think it speaks volumes about the attraction the US has, even amongst its worst enemies.

TP: War is also a spectacle in America, where people are conditioned, by films, to view conflict a certain way—where America is always on the side of the Good. Do the French also view war in this way?

RS: French public sees war not as a game, or an object for movies, but as something real, that involved their ancestors and that happened on their soil. Americans sees the heroes, who sometimes are their ancestors who liberated Europe. But they have never felt war on their soil. I think it makes a huge difference.

TP: You also went to Russia. Tell us a little of what you saw there?

RS: What struck me most was that contrarily to what the sanctions were aiming at, Russia is not on its knees. The food stores are full and people are buying like in any Western countries. There is no shortage of anything, even in Donbass. I was able to get a genuine original Coke at a Georgian restaurant off the Red Square in Moscow. It was imported from Armenia. This example proves that whatever sanctions you inflict on a country, you can never stop business.

TP: You describe the Russians as being “obsessed with history.” What do you mean by this?

RS: The man in the street, even from very poor background, knows his history. The 20 million or so dead soldiers in WWII is something very present for the Russian public. It is not only Putin’s obsession. It is widespread.

TP: What is life like for ordinary people in the Donbass and eastern Ukraine that is now part of Russia?

RS: Hell, near the frontlines, where a few people decided to stay. In general like in all wars, people strive to make ends meet. They don’t necessarily agree with the Russian invasion but they go along with it in order to protect their family. People live in fear. And it’s the same on the other side. The notion of being pro-Russian or pro-Ukrainian often depends on the reality of everyday life in the place where you live. You don’t choose a side. The side chooses you.

TP: What does Europe hope to gain by prolonging this war? By continually supplying arms? Why doesn’t Europe work to bring peace?

RS: Europe remains aligned with the US which is the only country that can stop the war and bring it to a negotiation-phase.

TP: What larger message do you want your book to convey?

RS: Peace!

TP: Thank you so very much for your time.