The Same Western Civilization that Attained the Highest Historical Consciousness and Produced All the Greatest Historians is Therein Destroying Its Historical Heritage.

One of the most startling historical truths is that Europeans invented the writing of history as “a method of sorting out the true from the false,” as a conscious search for a rational explanation of the causes of events, while rendering the results of their investigations in sustained narratives of excellent prose. The other peoples of the world, including the Chinese who maintained for centuries a tradition of chronological writers, barely rose above annalistic forms of recording the deeds of rulers or the construction of genealogies devoid of reflections on historical causation. This would not have been judged a controversial view a few decades ago. But in a Western world dedicated to multiculturalism, with universities making it their mission to promote an “inclusive” and “diverse” educational environment, there is a widespread impetus to acknowledge as equally valuable the historiographical traditions of non-Western peoples wherein the European tradition is seen as one approach among many others. These approaches include Islamic “universal chronography,” Chinese “encyclopedic, synchronic, and official historiography,” Australian Aboriginal “dreamings” of past events “organized spatially and morally rather than temporally,” or African “oral history of gathering, preserving, and interpreting the voices and memories of people.” Indeed, if there is a key difference between these perspectives it is that European historians have tended to be ethnocentric and arrogant in their supposition that they invented history. Among recent studies promoting a “global approach” against a “Europe-centered approach” is Turning Points in Historiography: A Cross Cultural Perspective , edited by Edward Wang and Georg Iggers. Academics are cited in this book stating that historical thought is not a monopoly of the West: “On the contrary, interest in the past appears to have existed everywhere and in all periods.” Western historiography is “not superior.” The claims of European colonialists on the “racial inferiority” of other cultures must be “refuted.” Just as Greek historiography provided a “basic form of historical writing that later exerted a cross-cultural influence in the West,” so was Chinese historiography “regarded as a model practiced by Asian historians, especially in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam before the nineteenth century.”

The initial aim of this essay was to counter this multicultural historiography by demonstrating its lack of veracity, explaining that Europeans originated the writing of history, wrote the greatest historical books, brought about the “professionalization of history” during the 1800s, which entailed the systematic and critical analysis of documents, from which point they would go on to write the best histories of the non-western world. Europeans were indeed the only people to exhibit a high level of historical consciousness about the way that history shapes our thoughts, culture, psychology, and institutions. But in light of my current scholarly preoccupation with the ways in which the ideology of liberalism, with its crucial principle of individual rights, is behind the promotion of diversity, race equity, and immigration replacement, I could not avoid the question why Western historians today are so enraptured with “provincializing” the history and achievements of their own civilization for the sake of an “inclusive” multicultural history. It became apparent to me that the consolidation of a multicultural historiography was not an arbitrary or isolated decision taken by a few academics, but part expression of a broader ideological matrix with deep origins in the history of the West itself. The more I investigated the historiography of the West, that is, the more I inquired about the history of history writing, about the histories that the peoples of the West have written, I came to the following hypotheses, which this essay will seek to explain:

- Europeans were responsible for the full development of history writing, surpassing since ancient Greek times the historiography of the other civilizations during their entire histories, consciously seeking to find the truth by evaluating the accuracy of the sources and analyzing historical causation. The Greeks and Romans did hold a cyclical view of history for whom “the nature of all things was to grow as well as to decay,” as the general consensus has it; however, this was a view based on a deep understanding of the varying psychology of human nature from times of simplicity and hardness (in the early stages of cultures) to times of affluence and decadence (in the later stages of cultures).

- The Hebrew Bible did go beyond an annalistic account of the deeds of kings, developing a historiography that was “national” or about a people as a whole, but without matching the historiography of the Greeks and Romans, who also initiated an ecumenical vision of “the whole inhabited world,” which would come to be combined with the “universal” historical vision of the Christians in their preoccupation with the “education of mankind,” and which reflected the fact that only Western peoples came to transcend in their cosmopolitanism the provincialism that is natural to cultures and that has prevailed in China throughout its history despite proto-universalist principles in Confucianism.

- The Old Testament did initiate a view of history as a purposeful and directional process from the beginning of the Creation to the future expectation of a Messiah; however, the New Testament enhanced the connection of God and history with its concept of the Incarnation, when the eternal Word and Son of God “became flesh and dwelt among us.” The subsequent Hellenization and Romanization of Christianity in the first centuries AD led historians to search for stages and directionality in the actual, empirical histories of humans, linking the eschatology of the Bible with the history of the Greeks, the creation of the Roman empire, and the kingdoms created by the Germanic peoples. The connection of Christian eschatology (Heaven and Hell, the Second Coming of Jesus, the Last Judgment) with the actual history of humanity, would lead Christians to initiate a “progressive” conception of history, as part of God’s providential plan, to search for an intelligible pattern in the gradual “education of mankind.”

- Only Europeans developed a true historiography characterized by a history of relatively continuous improvements, rather than by mere repetition of the historical styles of the past, as was the case in other civilizations, because only they experienced an increasing historical consciousness, a deep awareness of the passage of time in a directional way, rooted in their Christianity and cosmopolitanism, and in their actual epoch-making transformations, the rise and decline of Greece and Rome, the spread of Christianity, the invention of universities in the Middle Ages, among many other novelties, followed by the Renaissance and the continuous revolutions of the Modern era in warfare, art, architecture, science, philosophy, politics.

- But it was during the Enlightenment era that historians began to think systematically about the unique progression of the West in science and technology as well as in constitutional politics, and in the “rights of man”—against the forces of “darkness, ignorance, and vice,” which Enlightenment historians believed still held a tight grip over Europeans, and which needed to be defeated for the full potentialities of humans to be actualized in a future of plenty, harmony, and happiness. Man was a historical being in the process of achieving his full potentialities in the course of time.

- Modernist historians would secularize, not reject, the Christian idea of progress, while gaining a more “scientific” understanding of history, identifying definite stages in the growth of reason and liberty and in “the manners and morals of humans,” in terms of purely natural or man-made causes, rather than in terms of the “providential hand” of God. This idea of progress would come along with tremendous improvements in archival research and in historical methodologies, while the rest of the world would remain stuck with annalistic historiographies.

- The period between 1918 and 1970 would see the consolidation of a Grand Liberal Narrative, particularly in the wake of the defeat of Fascism in WWII, and the Cold War with Communism. This Narrative—the “Allied scheme of history”—would see in history a rational process of the growth of liberty, scientific and capitalist prosperity, with the United States as a model for the rest of the world, a result of thousands of years of Western evolution, combining the Greek democratic and rationalist legacy, Roman law, Judeo-Christian values, the Enlightenment and Free Markets.

- The German Historical School of the second half of the nineteenth century, known for raising to a higher level the professionalization and specialization of history, constituted a profound questioning of the liberal idea of progress with its nationalist advocacy of “the historicity of all knowledge and values” and its emphasis on the priority of the freedom of Germans as a people over the individual rights of abstract individuals. But German historicism would be thoroughly domesticated into a defense of “value-pluralism” according to which we should tolerate within each Western nation different cultural values except values that are intolerant to the “value-pluralism” of liberalism.

- Liberalism has an inbuilt progressive logic continually pressing for the “emancipation” of the individual from all traditional restraints, including sexual and racial collective identities, that infringe on the rights of individuals to choose their own lifestyle, backed by a new conception of “positive liberty” rather than mere “negative liberty,” a liberalism in which the government came to be assigned the role of reducing inequalities, increasing inclusiveness, and assisting in the “self-realization” of individuals.

- After the 1970s the “Rise of the West” grand narrative would come to be seen as an “unfinished project” requiring revision, starting with an acknowledgment of its “Eurocentrism” and the way the West had “underdeveloped” the rest of the world in its climb to supremacy, with old liberals gradually accommodating themselves to these revisions, confident in their defeat of communism in the early 1990s, announcing the “end of history, while including within its fold, as two sides of the same liberal coin, postmodern, environmental, multicultural, and global historical perspectives.

- Western civilization will soon cease to exist, becoming a hybrid of many races and cultures under the ideology of multicultural postmodern liberalism. The same civilization that produced the greatest historiographical tradition, becoming fully conscious of its historical trajectory, is now rewriting its past in the most malicious ways as a history of multiple peoples from its beginnings—against its “white supremacist” past.

The Greek-Roman Historiographical Legacy

Not long ago, before the onset of “progressive” diversity mandates, it was generally accepted that historical writing began with the ancient Greeks. R.G. Collingwood made the argument in The Idea of History (1946), once the best-known book in the philosophy of history in the English-speaking world, that “history is a Greek word, meaning simply an investigation or inquire”. Michael Grant, the famous classicist author of countless books, noted that the word “histor” in the classical Greek language referred to a learned man who settled legal disputes by looking into the accuracy of the events and the disputed allegations. From this legal term was derived the word “historie” as “a search for the rational explanation and understanding of phenomena.” In the “theocratic history” of Mesopotamia, accounts of past events consisted, as Collingwood wrote, of “mere assertions of what the writer already knows”, not based on answers arrived after research. The Hebrew scriptures were also theocratic history in that there was no research to “find” the “truth” about the past with authors consciously judging the veracity of sources. It is only with Herodotus’ book, The Histories, written around 430 BC, that we witness for the first time a real inquiry about the past “to get answers to definite questions about matters of which one recognizes oneself as ignorant.” The writings of Homer and Hesiod were likewise theocratic legends.

Herodotus was rightfully called “the father of history” for this reason, the first to write a historical inquiry which asked questions about the past based on the critical evaluation of the reports of facts given by eyewitnesses, as was the practice in Greek courts where one would cross-question the testimony of witnesses. Herodotus self-consciously explained that the purpose of his book was to present “the results of the enquiry [history] carried out by Herodotus of Halicarnassus. The purpose is to prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time, and to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by both Greeks and non-Greeks; among the matters covered is, in particular, the cause of the hostilities between Greeks and non-Greeks.” While in theocratic history, Collingwood adds, “humanity is not an agent, but partly an instrument and partly a patient, of the actions recorded,” in Herodotus we have descriptions of “the deeds of men…to discover what men have done and partly to discover why they have done it.” He sought to understand the reasons men acted the way they did.

John Burrow, an old stock British scholar, maintains that historical writing “based on inquiry” began with Herodotus. In his book, A History of Histories: Epics, Chronicles, Romances and Inquiries from Herodotus and Thucydides to the Twentieth Century, published in 2009, Burrow estimates we can only talk about “proto-history” in the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, and among the Assyrians and Hittites who came later, in the sense that they engaged in “record keeping” and chronological recording of the deeds of rulers and the construction of genealogies. A proper historical account, however, requires a conscious awareness about the veracity of the sources one relies upon. Herodotus “regarded himself as an auditor, a collector, recorder, sifter and judge of oral traditions about the recent or remoter past.” According to Mark Gilderfus, Herodotus “checked his information against the reports of eye-witnesses and participants and also consulted the documents available to him—inscriptional records, archives and official chronicles.”

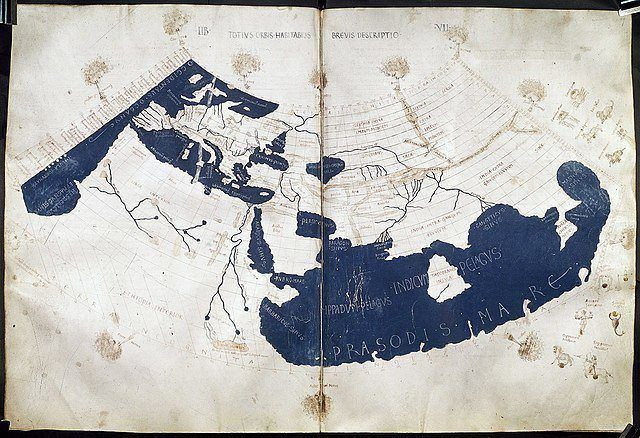

Collingwood correctly qualifies that The Histories of Herodotus could not but derive very little from written sources or “historical records” since there were few of these. This heavy reliance on oral sources restricted the writing of history among Greeks to events that happened “within living memory to people” with whom the author could have “personal contact.” The Greeks could not write “all embracing” accounts of the remote past and of the peoples of the world, “ecumenical history, world history.” For Collingwood, this lack of a worldly historical view meant that the ancient Greeks lacked a proper “historical consciousness.” Now, it is true, as Burrow notes, that Herodotus’ book “embodied extensive geographical and ethnographic surveys” of a variety of ethnic groups in the Mediterranean, North African, and Persian worlds, their clothing, diet, marriage, funerary customs, health and treatment of disease. It is for this reason that he is regarded, along with Hecataeus (b. 549 BC), as the originator of ethnography, the study of the culture of other peoples, for his “indefatigable questioning” of different ethnic peoples about their customs and morals. Still, I am inclined to agree with Collingwood that the unity of the historical mind of Herodotus was “only geographical, not an historical unity.” It was only after the conquests of Alexander the Great, and the creation of the Hellenistic and Roman empires, that the world became more than a geographical unity for the onset of a historical consciousness, which presupposes as a major condition an awareness of the histories of other peoples, reflections on the broader patterns of history as whole.

What about contemporary claims that other peoples were just as historically accomplished as the ancient Greeks? I will address these claims later on. For now, I will bring up John Van Seters’s thesis, articulated in a superb book of historical scholarship, In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History (1983), that an Israelite inaugurated the historical tradition of the West in the sixth century BC, roughly a century before Herodotus, in the so-called Deuteronomistic (Dtr) history of the Old Testament from Joshua to 2 Kings. The term “Deuteronomistic history” was coined in 1943 by the German scholar Martin Noth to explain the origin and purpose of the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. Noth argued that these books were the work of a single 6th century BC author. Elaborating this argument, backed by extensive sources, Van Seters uses the following criteria to identify history writing in ancient Israel: A) It has “a specific form of tradition in its own right” (as opposed to being merely incidental) to “explain or give meaning” in a literary way to the way things are, showing thereby “some awareness of the historical process” “to account for social change” and “provide new legitimation.” B) History writing is not primarily about the accurate reporting of past events, but involves recalling the significance of past events, as we find in Dtr history. C) While history writing examines the causes of present circumstances, in the world of antiquity at large “these causes were primarily moral;” modern theories of causation or laws of evidence should not be used as criteria. D) History writing has to be national or corporate in character, as was the case in Dtr history; chronological reporting about the deeds of kings do not constitute history.

Van Seters brings out the best of the annalistic form of writing in the Near East; for example, he shows that chronicles did date events rather precisely to day and month of the year, with some chronicles showing evidence of “research” or “a gleaning of materials about the past from various sources.” While these chronicles do not yet constitute history writing proper, they “created the potential for the historical ‘research’ and reconstruction of the past that is indispensable to the development of history writing.” What made Dtr history more than a chronicle was, “above all,” the fact that it was a history of a “people’s past,” of the founding of a “nation under Moses, through the conquest under Joshua and the rule of judges, to the rise of the monarchy under Saul and David.” In Dtr history, “the royal ideology is incorporated into the identity of the people as a whole” (rather than the ruler alone). “The doctrine of Israel’s election as the chosen people of Yahweh set the nation apart from other peoples…All other callings and elections, whether to kinship, priesthood, or prophecy, were viewed in association with the choice of the people as a whole…Nowhere outside of Israel was the notion of special election extended to the people as a whole.”

Van Seters shows similarities between the Dtr historian and Herodotus. If the former “gathered his own material…in the form of disparate oral stories,” so did Herodotus derive “very little” from written sources, or ‘historical’ records; his work was mostly based on eyewitness accounts.” All Hebrew historiography is written from a theological perspective,” but so is the book of Herodotus, The Histories, strongly interested in divine providence. “Like Herodotus, the Old Testament exhibits a dominant concern with the issue of divine retribution for unlawful acts as a fundamental principle of historical causality.” Both works are characterized by a thematic unity and a sustained prose narrative about a people conscious of their national identities (though Van Seters barely says anything about the emergence of a Greek national identity centered on their freedom in contrast to Asiatic despotism).

In reply to Van Seters: it is true that in Herodotus’ account the deities did play a role in human affairs, dreams, oracles and omens. But all in all, I am inclined to accept John Gould’s judgement that Herodotus “took the possibility of supernatural causation in human experience as seriously as he took the involvement of human causation.” In fact, Herodotus was “cautious in admitting” the presence of gods at work in human actions, not because of religious disbelief, but because of his “uncertainty” or “implicit acknowledgement of the limitations of human knowledge in such matters”, sometimes offering alternative possibilities for the occurrence of the events, or declining to identify the particular god involved. Herodotus’ list of reasons for the Persian war emphasized human motives, arrogance, excessive pride, blind enjoyment of riches, lust for power, which brought the wrath of gods, their intervention, but which nevertheless pointed to historical explanations relatively free of divine influence, which was not the case in Deuteronomistic history. By the time we get to Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, written a few decades after Herodotus’ Histories (430 BC), the gods ceased to influence directly the course of events, history is entirely caused by the actions of human beings, even if the historical actors remained guided by a belief in gods, oracles, or divinations.

Herodotus consciously addressed the issue of historical accuracy in a way that the Dtr historian did not. He may have relied almost entirely on eyewitness accounts in writing about the contemporaneous subject he was addressing, the Persian Wars, but once we reach Thucydides, we have a historian who amplify the need for historical veracity, for accuracy in the reporting of events, contrasting his inquiry with that of “prose chronicles, who are less interested in telling the truth than in catching the attention of the public, whose authorities cannot be checked”. He willfully restricted himself to contemporary history and eyewitness accounts knowing that the “passage of time” made accounts of early Greek history “unreliable.” This is the point. Even if we were to agree with everything Van Seters says, Herodotus was just the beginning of Western historiography. While Near Eastern and Israelite historiographical traditions ceased, stagnated, or barely improved, Europeans would go on to build upon their earlier achievements, and eventually develop a full historical consciousness, which is incredibly hard to achieve.

According to J.B. Bury, known for insisting that history should be a “science” rather than a branch of “literature,” Thucydides’ book was “severe in its detachment, written from a purely intellectual point of view, unencumbered with platitudes and moral judgments, cold and critical.” For Nietzsche, Thucydides was “the grand summation, the last manifestation of that strong, stern, hard matter-of-factness instinctive to the older Hellenes.” What Nietzsche admired, though, was not Thucydides’ neutral impartiality per se, but that his values were not that of a Platonist seeking to escape the harsh reality of human struggle and conflict in a realm of perfections. It was Thucydides’ realism, his ability to deal with the world as it was that appealed to Nietzsche, his rigorously clinical assessment of human nature. Edith Hamilton, author of the once very popular and gifted book, The Greek Way (1930), insists that Thucydides wrote his book “because he believed that men would profit from a knowledge of what brought about that ruinous struggle precisely as they profit from a statement of what causes a deadly disease.” Hamilton brings out Thucydides’ concern with the causes of the war, how he differentiated triggering incidents affecting the timing from the ultimate cause of the war. The confrontation between Athens and Sparta was not generated by misguided humans who could have been dissuaded into a different course of action; no, the Athenians were driven to imperialism, seeking threatening alliances against Sparta, by the natural human obsession with dominating others; and Sparta was driven to react knowing that lack of action would simply invite further hostilities by the Athenians and others. This is why Thucydides wrote a book “written not for the moment, but for all time.” In the words of Hamilton: “It was something far beneath the surface, deep down in human nature, and the cause of all wars ever fought. The motive power was greed, that strange passion for power and possession which no power and possession satisfy. Power, Thucydides wrote, or its equivalent wealth, created the desire for more power, more wealth. The Athenians and the Spartans fought for one reason only—because they were powerful, and therefore compelled to seek more power. They fought not because they were different—democratic Athens and oligarchic Sparta—but because they were alike. The war had nothing to do with differences in ideas or with considerations of right and wrong. Is democracy right and the rule of the few over the many wrong? To Thucydides the question would have seemed an evasion of the issue. There was no right power.”

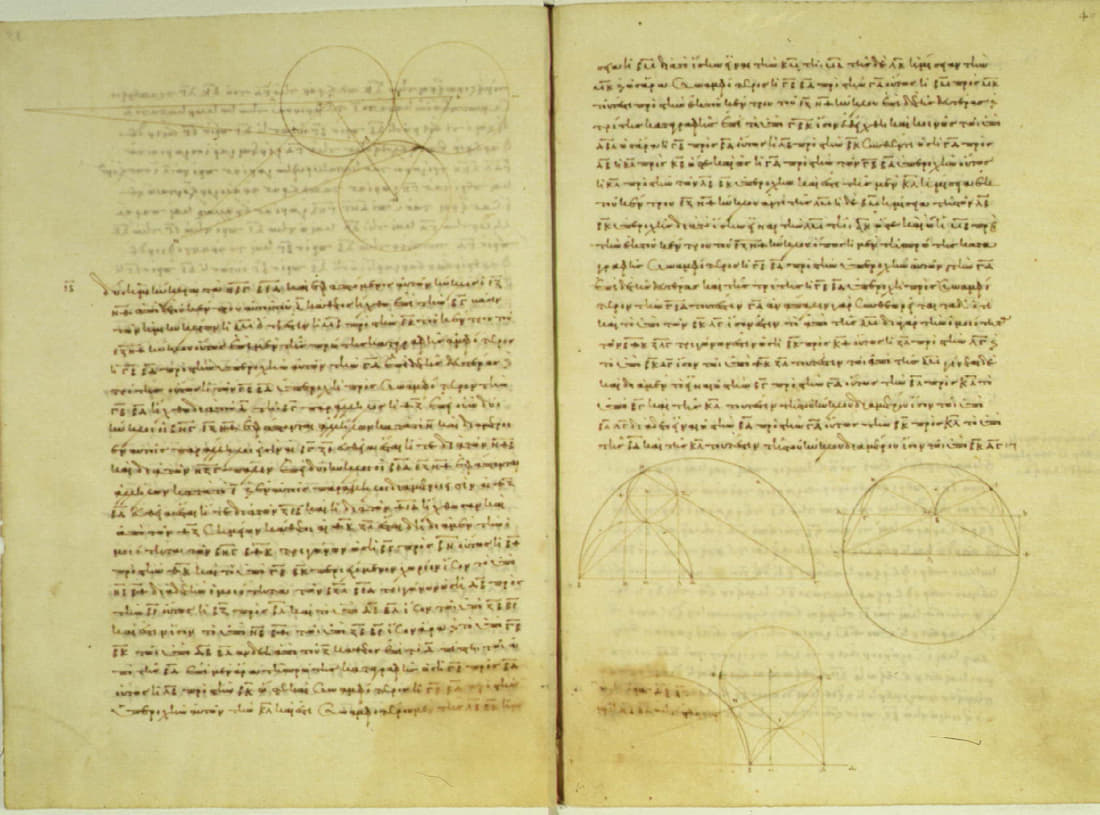

This clinical analysis of human nature in history would never find expression in the historiographical traditions outside the West. There are many timeless insights in Thucydides about the natural impulses of humans and their varied expressions in different characters and circumstances. Among my favorites is: “Self-control is the chief element in self-respect, and self-respect is the chief element in courage.” He and Herodotus started a historiographical tradition that would last continuously for over a thousand years. We can only go over the surface. Diodorus Siculus (first century BC), known for writing Bibliotheca Historica in 40 books, of which 15 survive intact, mentions many historians on whose works he relied upon. Some refer to this book as a “Universal History” both for its comprehensive coverage (from the mythic history of the destruction of Troy up to the death of Alexander the Great, including the early centuries of Rome), and for its worldly geographical description of Egypt, India and Arabia to Europe. He called it “Bibliotheca” in acknowledgment that he was assembling a composite work from many sources. This was not a history based on eyewitness accounts but a history based on the authority of prior historical authors/sources. The authors he drew upon include Hecataeus of Abdera, Ctesias, Ephorus, Theopompus, Hieronymus of Cardia, Duris of Samos, Diyllus, Philistus, Timaeus, Polybius, and Posidonius.

Siculus however was really a “compiler” rather than a universal historian since his work was descriptive in character, lacking an interpretative scheme. His predecessor Polybius (200-118 BC) may be said to be the original ecumenical or universal historian, in full awareness that in trying to answer the question in his book, Histories, why “the Romans succeeded…in bringing under their rule almost the whole of the inhabited world” and writing about how “the affairs of Italy and of Africa are connected with those of Asia and of Greece and all events bear a relationship and contribute to a single end,” he was indeed, in his words, the “first” “to examine the general and comprehensive scheme of events” and to look at history as an “organic whole.” In answering this question, Polybius raised the analysis of historical causality to a higher level of precision, by adding the “how and why” to the “who, what, where, and when” of Thucydides. He sought “to record with fidelity what actually happened,” with profuse references to prior historical accounts. Since Polybius covered a long-time span of history, 264-146 BC, unlike Herodotus and Thucydides, he could not rely on eyewitness accounts only. Fortunately, in his time, there were already many authoritative “works of previous historians who had already written the histories of particular societies at particular times,” including Rome’s own careful preservation of memorials and ancestral portraits.

His universal perspective was also visible in his effort to provide a sweeping explanation of the rise and fall of civilizations in general, expressing for the first time, in a cohesive manner, the principle of cyclical history. States experience a natural cycle similar to biological organisms, characterized by growth, zenith, and decay. Primitive kinship first emerges and develops into monarchy, monarchy devolves into tyranny, and eventually tyranny is replaced by the aristocratic rule of the best (the men of virtue, piety, and courage who created Rome). This rule then degenerates into oligarchic privilege and excess, followed by democracy and finally, mob rule. He believed that the Roman state was superior to all prior forms of government in combining the best of three forms of rule, monarchical (elected consuls), aristocratic (senate), and democratic (popular assemblies. But in his estimation, while this mixed policy could slow down the cycle, it could not deter the eventual decomposition of Rome.

Another revealing quality of ancient Western historiography was its preoccupation with the moral character and personality of great men. This individualism, rooted in the heroic aristocratic ethos of Indo-Europeans, as expressed in their timeless bards and poems, which recited the heroic deeds of legendary figures, with the main characters identified by name and personality, as was the case in the Iliad, would find expression in the preoccupation we already noted above about human nature and the personal qualities of leaders, a phenomenon utterly lacking in non-western historiography. Who can forget the famous Parallel Lives of Plutarch (46-120 AD), mandatory reading for every young European man not long ago? Nineteenth century “positivists,” who believed that historians should remain objectively preoccupied with the facts alone without judgments, downplayed Plutarch as a historian for his moralistic judgements about the virtues to be emulated and the vices to be avoided in his illustrations of great men. Yet, Plutarch “read voraciously, and faithfully reported what he found in a wide variety of sources.” He was “one of the most educated men of antiquity” who knew and quoted “all the major Greek historians” and supplemented his narratives with information from letters, inscriptions and public documents. His Lives were not hagiographies glorifying great men, but an effort to demonstrate the importance of rational self restraint against irrational passions, exhibiting a high sensitivity to the dynamics of human motivation, the interaction of contrasting traits and how they can complement each other within the same character, combined with keen observations about the physical appearance of the characters, thereby showing a keen insight into the variety and complexity of human behavior. Never in the history of the non-western would we witness a book like Plutarch’s Lives, which consists of a series of paired biographies of the great men who established the city of Rome and consolidated its supremacy in comparison to their Greek counterparts, written with such elegant prose and narrative flair.

It has been said that Greek/Roman historiography was limited by its view of an unchanging human nature. Michael Grant, in The Ancient Historians (1970), says that “Plutarch has no idea of dynamic biography…The ancients were still mostly convinced that a man’s character is fixed; at any point in his life, he is what he always was and always will be.” This idea, we shall see below, would be rejected by modern historians around the 1700s, starting with historians of the “Scottish Enlightenment,” with their stage theory of history and their observation that with the rise of commerce and constitutional monarchies, there was a noticeable “improvement of manners” among men. This view also nurtured the equally influential and related current of “historicism,” which came in many conflicting varieties, but essentially argued that all human activities, such as science, art, customs, philosophy, are shaped by their history, not by an unchanging human nature.

It is more complicated. Herodotus did imply in his ethnographic observations that human nature manifests itself differently (in customary practices) in different geographical settings. The claim that the cyclical view of history “was entailed by a belief in an unchanging human nature” forgets that this view postulates a dramatic alteration in the characters of humans, from virtuous qualities during the rise of states, to decadent traits as wealth, peace, and ease become the new reality. The decline of the Roman character is a pervading theme of Roman historiography; already apparent in Cato the Elder (234-149 BC), author of Origins, of which only fragments survive, about the beginnings of Rome up until the victory over Macedonia in 168 BC. Cato eulogized the “Spartan” austerity and simplicity of the early men who built Rome, and lamented the effeminate influence of Greek learning. Sallust (86-35 BC) saw the old Roman virtues of frugality and piety decline under the influence of luxury and Asiatic indulgences and taste, in the first century BC. “Growing love of money and the lust for power which followed it engendered every kind of evil. Avarice destroyed honour, integrity and every other virtue, and instead taught men to be proud and cruel, to neglect religion and to hold nothing too sacred to sell… Rome changed: her government, once so just and admirable, became harsh and unendurable.” But, according to Sallust, it was not all about character decomposition; he also saw an intensifying civil strife in late republican Rome between two factions: the old patrician class in control of the Senate, and the plebeians in control of the popular assemblies. Sallust, who was “a popularis” supporter of Caesar, praises Tiberius Gracchus in his The Jugurthine War (41-40 BC), recognizing the Gracchi brothers as “vindicators of the liberty of the people” against the “shamelessness, bribery and rapacity” of the old aristocracy, as he put in The War With Catiline, grabbing the spoils of war and leaving citizen farmers landless, as they were burdened with prolonged military service.

Along with its psychological portraits, Western historiography was uniquely characterized by an “elaborated, secular, prose narrative” combined with a literary ability to draw the reader into the events and personalities, in startling contrast to the bureaucratic, impersonal, and annalistic reporting that one finds for centuries in non-western historiography. Roman historians were educated with strict rules for prose composition, and in the art of literary rhetoric. They took delight in their character portraits. Criticizing them for their moralizing judgements betrays a lack of appreciation for their psychological insights, the inevitability of judgements in historical writing and the importance of bringing out the dramatic character that is actual history. Here is Sallust writing about Lucius Sergius Catilina (108-62 BC), a Roman politician and soldier, corrupted to his innermost being by his lust: “His unclean mind, hating god and fellow man alike, could find rest neither waking nor sleeping; so cruelly did remorse torture his frenzied soul. His complexion was pallid, his eyes hideous, his gait now hurried and now slow. Face and expression plainly marked him as a man distraught.” Not until Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in the late 1700s, would anyone see the need to supersede the historiography of ancient Romans. Sallust, Livy, and Tacitus were thought to be unsurpassable in their narrative abilities, character portraits, analysis of Roman’s political history and detailed description of its wars.

Livy (59 BC-AD 17), immortalized for his monumental history of Rome in 142 books, of which 35 survive, from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in 753 BC through the reign of Augustus in Livy’s own lifetime, is widely acknowledged as a “superb narrator.” He understood that his accounts of early Rome have “more of the charm of poetry than of sound historical record,” although future antiquarians have learned a lot about the foundational myths of Rome from these accounts. As in Sallust before him, in Livy, as John Burrow writes, “the question of moral fibre, nurtured by war, weakened by peace and ease, became the core of Roman history.” Livy raised to a higher level of explanatory sophistication the social historical perspective already incipient in Sallust, by accentuating the significance of the conflict between the old patricians and the plebeians, which he traced back over the centuries, recounting how these two classes had managed to get along with the abolition of debt enslavement, the redistribution of land, and the eventual opening of the highest offices (consulships, censorships) to wealthy plebeians, and how in the first century BC this consensus broke down as different sections of the plebeians, a rich elite allied with the patricians, and a poor class of smallholders, who were the backbone of the citizen army, could not resolve their differences. Upon returning from military service to their neglected farms, these small holders, as they struggled to pay debts and taxes, would lose their farms, which made the practice of citizen soldiers obsolete, and led to the rise of private professional armies. It was Livy’s view that Rome had managed to rise and survive major threats, such as the disaster of Cannae, insofar as the upper classes had acted in moderation, bringing the plebeians to rule alongside them, and redistributing the spoils of war. Roman “firmness” and “sternness” was rooted in this social reality, whereas Roman decadence was rooted in the lustful rapacity of a wealthy oligarchy expropriating the citizen farmers. At the same time, Livy also pointed to demagogues who stirred up the plebs towards mob rule out of their tyrannical ambition. It has been said that the historiography of ancient times contained truths valid “for all time.” In his Discourses on Livy (1517), Machiavelli explained, after a close reading of Livy, that all forms of government—monarchical, aristocratic, and democratic—are flawed, and that it was the good fortune of the early Roman republic to combine traits from these three. The inherent conflict of interests between the nobles and the people can turn out to be constructive as long as there is an institutional balance of power in which tribunes of the people can wield power. There is never an ideal political order in which conflict is avoidable.

Perhaps the most admired Roman historian is Publius Cornelius Tacitus (56-120AD). Tacitus enjoyed a very high reputation from the late sixteenth to the late seventeenth century, admired by Gibbon for “the force of his rhetoric…to instruct the reader by sensible and powerful reflections.” He wrote primarily about the relations between the Emperor and the Senate, not the wider world of the Empire, based on the testimony of eyewitnesses, published transactions of the Senate, news of the court, collections of emperors’ speeches, and memoirs. In his didactic concern “to ensure that merit is recorded, and to confront evil deeds and words with the fear of posterity’s denunciation,” it has been said that he was a moralizing historian. His focus was on the motives of the characters, exposing hypocrisy and dissimulation. Some praise the brevity of description of his Latin style, their “epigrammatic” character, or lack of ornamentation. The period he covered, mostly the first century AD, offered only meager examples of virtue—which may be why he praised the Germanic peoples in what may be his best-known work, the fascinating ethnographic essay titled Germania. Linked to the Third Reich, this essay would also play a key role in the construction of a historiography identifying freedom as the most important ideal of Western history. He observed the Germans in their own terms rather than in light of Roman values, showing admiration for German sexual temperance, dignity, courage, and loyalty—without falling prey to the modern myth of the noble savage, describing as well their drunkenness, idleness and quarrelsomeness. It was this lack of discipline, he believed, that gave Romans an advantage over the formidable German warriors. In the early modern period, as Germania became increasingly known, it encouraged historians to delve deep into the pre-Roman past of Europe. Historians would discover a conception of freedom that predated the Greek, Roman and Christian conceptions—what I would call, in my book Uniqueness of Western Civilization (2011), a primordial ethos of aristocratic and heroic freedom. Francois Hotman, in his Franco-Gallia (1573), concluded, after a thorough study of numerous chronicles of Europe’s early history, that the ancient kings of France were elected and could be deposed, and that French representative institutions, the Estates General, were descended from the old Germanic assemblies of aristocrats. Future authors would argue that the feudalism of the Middle Ages, the contractual relation between lords and vassals, was derived from the Teutonic comitatus, the brotherhood of warriors. Montesquieu located this Germanic freedom in the Anglo-Saxon nations, which he developed into a modern doctrine of republican liberty, and identified Britain as the best example of the preservation of Germanic freedoms, whereas in France he saw a nobility that had surrendered its liberty by becoming a bureaucratic servant of the absolutist state. The constitution of Britain, after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, consisted of a mixture of monarchical, aristocratic (House of Lords) and democratic elements (Commons), with freedom of thought.

The Emerging of a Christian Historical Consciousness

For all we have said about Greek and Roman historiography (and there were other historians, such as Suetonius, Appian, and Casius Dios) cotemporary scholars invariably agree that the ancients remained a “non-historical” people. Herbert Butterfield is convinced “the Greeks did not achieve historical mindedness, and never could have achieved it, because they had the wrong view of time and the time process.” The Greeks “only knew of a comparatively short history behind them—they thought that the historical past extended back for only a very few hundred years.” But even in the case of the Romans, despite some of their long-term accounts, including a 1400-year history by Casius Dios, Collingwood insists that Roman historians thought of Rome as an “unchanging substance,” “the eternal city,” experiencing cyclical changes but no identifiable stages of development. Livy never sought to explain how Roman institutions came to be, how they changed over time, other than noticing, if I may add to Collingwood’s explanation, the virtues that made possible its rise and the vices bringing about its decline. It was a history without periodization about a city that seemed to be ready-made before history began. Roman historiography was also “particularistic,” self-centered around Rome, without grasping the historical dynamics of other people and their place within the historical process. Tacitus distorted history, Collingwood adds, by “representing it essentially as a clash of characters” portrayed as either “exaggeratedly good” or “exaggeratedly bad.” As talented as Tacitus was in his character-drawings, his approach encouraged the narrowly circumscribed perspective of seeking the causes of historical events in the personalities of the main actors—a retrogression from the world historical perspective of Polybius.

The Marxist historian E.H. Carr, author of a 14-volume work covering the first twelve years (!) of the history of the Soviet Union, argues similarly that “the classical civilization of Greece and Rome was basically unhistorical.” For Thucydides, “nothing significant had happened in time before the events which he described and nothing significant was likely to happen thereafter.” He goes on to explain in his insightful small book, What is History? (1961), that a cyclical view of history, the sense that history is “not going anywhere,” is devoid of a proper historical consciousness. One must have a sense that there is a “direction in history” to interpret the past properly. While a historian does not have to believe that history is progressing “towards the goal of the perfection of man’s estate on earth,” without a conception of progress, which entails a history that is indeed characterized by development, such as an increasing capacity to understand and master the laws of nature and improve the living standards of people, we can’t speak of “historical consciousness.” Carr does not believe in “Divine Providence,” a “World Spirit,” or “Manifest Destiny,” that is, in an all-powerful force guiding men and the course of events. But he believes that “it was the Jews, and after them, the Christians, who introduced an entirely new element by postulating a goal towards which the historical process is moving—the teleological view of history.” It was “Jewish-Christianity” that gave history “meaning and purpose.”

According to Collingwood, Christianity contributed the following to the eventual rise of a modern historical consciousness: the universalism that all persons are equal in the sight of God, that “all peoples are involved in the working out of God’s purpose,” and that therefore a Christian can’t remain content with the particularistic history of one people but must strive for a universal history. The events that occur in the world must be ascribed to the workings of Providence, which means that one must try to detect an intelligible pattern in the overall history of humans, and treat earlier events as leading up to, or preparing for, God’s ultimate plan. This means, I would add, that in order to make sense of history’s pattern, history must be divided into epochs, each identified for its contribution to progress and for the ultimate plan.

The flaw in this interpretation is that it does not draw a distinction between the Old and the New Testament view of history, and the subsequent Hellenized and Romanized Christian conception articulated in the first centuries AD. The Old Testament, to be sure, offered a purposeful and directional view of history from the beginning of time, from the Creation and the expulsion from Paradise of Adam and Eve, as a result of their original sin, to the second beginning of mankind with Noah, after the flood, followed by God’s promise of land to Abraham, demonstrated in the liberation of Jews from Egyptian captivity, followed by numerous events with references to peoples and civilizations in the Near East, Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria Persia and Jerusalem. The Hebrew Bible, Van Seters is correct, offered a dramatic long-term narrative of a people intensively preoccupied with their past, the first accounts to go beyond the Royal annals of the Mesopotamian/Egyptian empires, to produce a history of a people as a whole, the Jews, with quasi universalist aspects in its account of the Creation and the Flood.

The Old Testament conception, nevertheless, was about a particular people, the Jews, and, in this respect, it was not universal. It was a conception that remained preoccupied with the Jewish historical experience, to a final act of God that would signal the end of history, with dreams of a Messianic kingdom, as it grew pessimistic about the actual events of its history with the lost of Jerusalem, the destruction of the Temple, and with the dispersion and exile of Jews in foreign lands. The Bible as a whole, both Old and New Testaments, did not try to make sense of actual human historical events beyond the experiences of Jews; and did not try to discover a meaningful pattern in the empirical happenings of world history. History in the Bible is meaningful because it is oriented toward some transcendent purpose, the future expectation of a Messiah, but this expectation is not seen to be developing through successive historical stages since the truth has already been revealed. This is a view that Karl Lowith holds in his philosophical meditation, Meaning in History (1949). History is directed by the providence of God’s supreme insight and will, but God’s ways are hard to make out and cannot be comprehended by reason. The message of the Bible is that we must trust God’s justice in spite of manifest evil in the world, and faithfully wait for justice to be done on the Day of Judgement. The Biblical conception is similar in some respects to the Greek cyclical acceptance of fate, in the way it looks at history through all the ages as a story of mere genesis and disintegration, action and suffering, pride and sin, as a “continuous repetition of painful miscarriage and costly achievements which end in ordinary failures.”

But Lowith is rather indifferent towards the historiography of subsequent Christians who sought to discover in actual history the spiritual unfolding of salvation. Even thought the New Testament as such does not seek out to make sense of the actual history of the Hellenistic-Roman world from which it emerged, subsequent Christians, as Butterfield says in The Origins of History (1981), “could not help vindicating the idea of the Jesus of History, Jesus the man who had lived at a certain time and in a definite place.” The religion of Christianity “was fastened to the hard earth” through “their continuing concern about the possible imminent coming end of the world, and their contact with Greek philosophy” and, I would add, through the very concept of the Incarnation and the Cross. Christianity departs from the Old Testament in the consummated advent of Jesus which signifies that God has given His grace through the hands of His Son who in his sacrifice has brought redemption to all humankind. Humans are no longer fully corrupted but are newly capable of achieving ethical and eschatological goals in this world. The Christian God is not impersonal, unknowable, and separate from our world. He is both transcendental and immanent, for in the Incarnation, and the idea that Christ is both fully God and fully human, the unfathomable God of the Old Testament finds concrete expression in history. Christianity recognized the dignity of the material world and its ability for expressing the Spirit. Christ is the image of the invisible deity here on earth and human action can bring about the world’s transformation.

In line with the incarnation and immanence of God on earth, Jesus added an “ethics of love, or compassion,” which cultivated “a new sensitivity to human suffering,” which motivated Christians to struggle against evil in this world, which set in motion a historical process of moral progression. This religion brought the hope that it was possible to create a “better world,” for it was a religion that no longer saw suffering as unchangeable, but called upon believers to feel responsibility for the suffering of others. In contrast to Greek pagan ethics and Roman stoicism, which held that it was folly to struggle against the destiny of human limitations and realities of the world, there was a feeling of hope and progress embedded in the ethics of Christianity according to which humans on this earth could improve the human condition and bring about the advent of the Kingdom of God. Non-western religions conceived of salvation as something to be achieved by escaping into the “world behind” or the “world beyond.” But among Christians a sense emerged that history was not a cycle of time but a “forward-moving” process, a linear movement from Creation to the “end of time.”

But we also need to add that it was only with the Hellenization and Romanization of Christianity in the first centuries AD that we see philosophers and historians trying to make sense of the connection of God and world history. The New Testament taught that God had connected himself to the happenings of the world through the historical figure of Jesus in the flow of time from the Creation to the eventual Second Coming, which made it impossible for Christians to view history as cyclical but instead postulated a beginning, a central event, and an ultimate goal. The historians of the first centuries AD would take this idea further by making Christian sense of the history before the coming of Jesus, and the history of their own times. Irenaeus (130–202) thus interpreted the Old Testament as the preparation for the New, as an “upward” development which demonstrated the divine “education of mankind.” God, by becoming man through Christ, restored humanity to being in the likeness of God, which humans had lost in the Fall of Adam. He saw an upward movement from the period of infancy in which Adam failed God’s command and elicited God’s punishment, to that of Christ (the new Adam) who represented the new head of humanity and undoes Adam’s disobedience. This idea of the “education of mankind” was developed further as Christians wrestled with the historical meaning of Greek philosophy as well as the meaning of Rome as a “universal” empire in God’s providential plan. Early Christians neither rejected outright nor accepted Greek philosophy completely, but took a historical view by arguing, as Justin Martyr (100–165) did, that Greece represented a stage in the growth of truth towards fullness in the revelation of Christ. Christ was “known in part even by Socrates.” Clement of Alexandria 150–215), likewise, wrote about God planting the seeds of Christian revelation in Plato and Aristotle.

As the expectation of the Second Coming weakened, Christians developed a conception of historical time that went beyond the finality of the Last Day, guided instead by the promise of redemption in the course of time, for the Creation was not perfect to begin with, but needed time to grow and mature. Before the Last Day, Christians had a historical role to play: “the good news must be preached to all the heathen.” For God to accomplish his mission to mankind, a long span of time may be required. Origen of Alexandria (185-253) and his disciples strove to give meaning to the history of Rome. The “seeds” of Christianity had been sown by Christ in every human since Creation; God had attended to the best in Greek as deliberately as he had revealed the Law to the Jews. The universal peace created by Rome was intended to create the conditions for the foundation of a universal Christian Church. Christians could not therefore discard as futile, as part of a meaningless cycle, the histories of Greece and Rome, for these histories were also part of the divinely ordained progress of humanity.

With the conversion of the emperor Constantine the Great (272–337), the Pax Romana came to be widely accepted as God’s instrument for the dissemination of the Gospel over secure roads and seas. It was the historian Eusebius (260/265-339), a close advisor of Constantine, who integrated Rome into Christianity’s “upward” “education of mankind,” generating thereby the possibility of a truly universalist conception of the concrete history of humans. He did so in his Chronicle and his Ecclesiastical History, within a time scale and a chronological time-line that included the rulers and dynasties of the Assyrians, Egyptians and other peoples, as well as the main figures and events of the Old Testament, the work of the Apostles to the deaths of St. Paul and St Peter, through to the making of Christianity into the official religion by Constantine in 313. Eusebius provided a chronology of the major world historical events, placing the birth of Chris in the year 5198 from Adam or 2015 from Abraham, on the basis of many documents and textual sources to ensure a proper record. He was the author of many books based on carefully collected materials, a man of indefatigable industry, though we must not assume he was a better historian than the Greeks/Romans, who were literary masters of prose, engaging narrators, and insightful psychological analysts. In the words of Michael Grant, Eusebius’ narrative was “uninspiring,” “dull, muddled and haphazard,” with a “cumbersome, obscure and slovenly Greek.”

While Saint Augustine (354-430) was not a historian, he offered a profound expression to the idea that truth is inseparable from historical time and that history points towards an end entailing “the education of the human race.” Augustine rejected the Greek idea that history goes on repeating itself endlessly through time and that nothing new emerges with each cycle. Any cyclic view is inherently unable to grasp the meaning of time. In his Confessions, he asked: “For what is time?” He answered: “If nothing passed away, there would not be past time; and if nothing were coming, there would not be future time; and if neither were, there would not be present time.” Therefore, humans could not have conceived of time if history was characterized by cycles repeating themselves throughout endless ages. In The City of God, he argued that God created time: “For, though Himself eternal, and without beginning, yet He caused time to have a beginning; and man, whom He had not previously made He made in time, not from a new and sudden resolution, but by His unchangeable and eternal design.” From this initial creation of man in time, in the beginning, we can witness thereafter, in the flow of historical time, “the education of the human race.”

Robert Nisbet, however, pushes too far the argument that there is in Augustine an idea of progress in a linear and cumulative way. Lowith may be more judicious in his claim that “for Augustine the historical task of the Church is not to develop the Christian truth through successive stages but simply to spread it, for the truth as such is established.” But it is hard to deny that Augustine was interested, in the words of Butterfield, “in the whole drama of human life in time.” Nisbet does make a good case that “it is the Greek strain in Augustine that causes him to put God in a developmental, progressive light.” We read in Aristotle that everything has a telos, a purpose, a striving to actualize its highest potentialities, and within man there is a potential for rational and moral perfection. Augustine appears to see the unfolding of this potentiality in the course of historical time rather than, as the Greeks did, within the biological lifetime of individuals on their own. Influenced perhaps by Eusebius’ attempt to write the actual history of humans within a Christian scheme, Augustine did write of epochs, with an eight-stage referring to the resurrection of Christ, and history culminating in a last stage, a blissful period on earth, prior to entry of the blessed into heaven. Conflict, suffering, torment, fire, destruction, would be endemic, until the attainment of the heavenly city, where humans would be “delivered from all ill, filled with all good, enjoying indefeasibly the delights of eternal joys, oblivious of sins, oblivious of sufferings.”

Other historians would follow, such as Paulus Orosius (375/385-420 AD), a pupil of Augustine, who wrote The Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, “considered to be one of the books with the greatest impact on historiography during the period between antiquity and the Middle Ages,” integrating into a Christian scheme the history of humanity starting with the Creation up to the times in which he lived. Scholars acknowledge him as “the first Christian universalist history” with his argument that there were four successive historical empires, Babylonia, pagan Rome, Macedonia and Carthage, followed by a fifth empire, that of the Christian Rome of his time, as the inheritor of all the achievements of the past. But something was missing in the early medieval Christian universalist histories: a lack of integration of the superior historical inquiries of the ancient Greeks (Herodotus, Thucydides, Polybius) and Romans (Livy, Sallust, Tacitus), with their higher preoccupation with checking the trustworthiness of their sources, explaining the reasons for the occurrence of events, and writing detailed narratives with excellent prose. One can indeed say that the ancients would not be surpassed until modern times.

But we must not thereby neglect the achievement of medieval historians in their integration of the new barbarian Germanic kingdoms within the Christian scheme, ascertaining the designs of Divine Providence in the events and kingdoms witnessed. The “universalism” of the History of the Franks by Gregory of Tours (539-594), a Gallo-Roman aristocrat, consisted of a few opening pages summarizing Biblical events, the Incarnation of Christ, and the history of the Church, before narrowing the focus to Gaul, in what was then a very localized European world of isolated regions. He related many miracles as examples of the ever-present power of God in the occurrence of events, with portents as warnings from God of things to come, such as lights in the sky, comets, wolves in the city. Reading this book as an undergrad, I relate to John Burrow’s observation about Gregory’s recording of countless acts of violence, homicidal feuds, in an impassive fashion, as if these things were natural, drily recounting Clovis’s habit of unexpectedly bisecting people with an axe, while believing that Clovis “walked before Him with an upright heart and did what was pleasing in His sight.” It is not that he lacked any feelings, as we can sense in a passage where he laments the death of children in a plague: “And so we lost our little ones, who were so dear to us and sweet, whom we cherished in our bosoms and dandled in our arms, who we had fed and nurtured with such loving care. As I write, I wipe away my tears” [76]. Gregory simply took for granted the imperatives of power.

For Burrow, Gregory can “hardly” be viewed as a “great historian,” for his narrative was “too episodic, too uninterested in generalization and context.” But things would improve with the onset of the Carolingian Renaissance, which brought a revival of letters, accompanied by wide-scale copying of classical texts, under the reign of Charlemagne (768–814). A product of this age was Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne (830), which became a model for subsequent biographies, such as Bishop Asser’s Life of Alfred the Great (893). Einhard was fortunate to have access to the work of Suetonius, a biographer during the time of Tacitus, author of Lives of Illustrious Men (the poets Terence, Virgil and Horace), including Lives of the Caesars. Suetonius is known for avoiding the heavy moralizing of Plutarch, “looking at personages with a cooler and more disenchanted eye,” and for attributing to Julius Caesar the famous phrase “the die is cast” when he crossed the Rubicon. Einhard offered keen insight into Charlemagne’s political success, battlefield strategy, foreign and domestic policies, friends, enemies, and personal habits. But the Carolingian empire soon disaggregated into separate feudal kingdoms, and, in the overwhelmingly rural world of this age, we find instead a type of historical writing that paid homage to a few Christian universalist principles before focusing almost entirely on the episodic events of local and national regions. It is hard for humans to have a historical consciousness without discerning a developmental pattern in history, accumulation of innovations, continuous growth of knowledge, improvement in manners and morals, to allow them to transcend a conception of time in terms of the natural cycles of the seasons and the cyclical succession of civilizations and dynasties. Traditional cultures tend to be, by their very nature, unhistorical, and therefore not able to develop a proper historical consciousness.

Nevertheless, progress there was, if intermittent and slowly. Countless chronicles, which laid the groundwork for the nationalist histories of ethnic Europeans in the future, were produced during the Middle Ages: The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (written in the late 900s, now recognized as a key historical source during the period following the Roman presence and preceding the Norman invasion in 1066), Chronicle of the Slavs (1170), Chronicle of Livonia (describing the conquest and conversion of Latvia and Estonia), Chronicle of Prague (completed in 1119, starting with the creation of the world, then describing the legendary foundation of the Bohemian state, and ending in 1038), Chronicle of the Poles, Chronicle of Novgorod (from the 900s to 1400)—to mention a few. These chronicles, as Ernst Breisach says, “usually reported events, item by isolated item, and their reason for recording an event was not its effects on the subsequent course of events but its being noteworthy in its own right or for instructing human beings about the spiritual cosmos they lived. In a chronicle, the conversion of one person could outweigh whole battles; the deeds of a humble woman would outrank the deeds of kings; and miracles, omens, visions, prophecies…could hold their own among the most impressive secular events.”

The emerging concept of causality, in which a given state of affairs was accounted for in terms of antecedent factors or events, evident in the work of Thucydides and Polybius, was abandoned in medieval historiography. Great historical works there were, but few and far in between. One of the most respected is Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Although the aim of this work was didactic, to record examples of goodness and wickedness, Bede is acknowledged as a “measured” historian “completely in control of his theme,” producing a history of the English peoples “generally chronologically lucid…[and] scrupulous in giving his sources.” Covering the history of England from the time of Julius Caesar to the date of its completion in 731, this book is considered one of the most important “primary” references on Anglo-Saxon history. Geoffroy de Villhardouin’s The Conquest of Constantinople, an eyewitness account of the Fourth Crusade (1199–1204), is also estimated by Burrow to be a proper history book in having a “coherent continuous narrative” rather than being a mere chronicle of events. Likewise, Burrow sees Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, depicting the Anglo-French rivalry during the Hundred Years War, as the work of “a master of fluent, controlled and relevant narrative.” William of Malmesbury’s The Deeds of the Kings of the English is judged by Breisach as an “encyclopedic survey,” widely read for its vigor and learning and for “reaching a literary level superior to that of preceding chronicles.” With the Roman historian Suetonius as his model, Malmesbury was a “careful, accurate, and conscientious writer,” who portrayed historical actors vividly.

But as much as medieval Christian historians tried to make sense of the course of history, they were frustrated in their inability to establish a clear connection between the idealized City of God and the chaotic and violent City of Man. Augustine, when asked why did God allow the city of Rome to be sacked by the Visigoths (in 410 AD) if the history of man was guided by Providence, drew a sharp contrast between the City of God, eternal, heavenly, awaiting us in the future, and the City of Man, characterized by pride, self-aggrandizement, and endemic conflict. He did not see in the City of Man, which reflects the actual history of man, a process of cumulative improvement, but a “shallow and corrupt reflection of the heavenly city because its founders” were “sinful men of the world.” The City of God, which reflected the ideals that God wanted for this world, would come only after the City of Man had been brought to an end. Augustine could not integrate the ideals of the City of God with the City of Man. The City of God represented the unchangeable ideals of Christianity, whereas the City of Man represented the changeable (unessential) values of man in the flesh. Augustine, and medieval Christian historians, could not overcome this dualism, because they could not detect actual progress in the City of Man. They were men, to use a Hegelian phrase, with an “unhappy consciousness,” a consciousness that experiences itself as divided within and against itself, frustrated by its inability to see the unity of God and human history. The historical consciousness of medieval Christians would have to await the modern era to see this unity, at which time it was secularized into a liberal idea of progress.

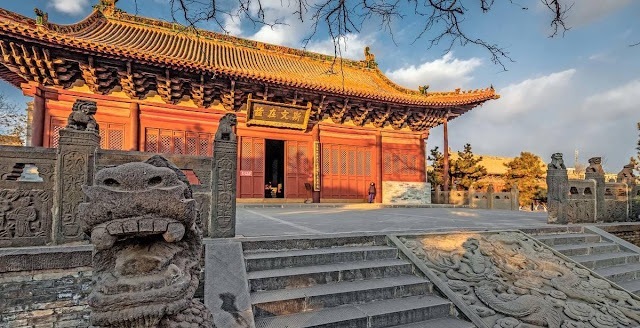

The Stalled Development of Chinese and Islamic Historiography

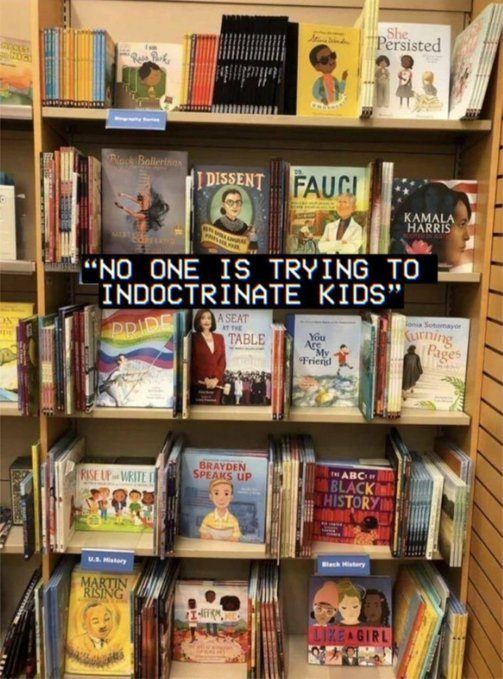

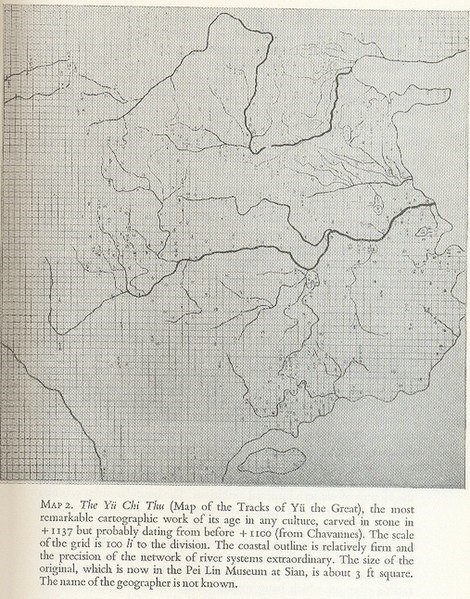

Did the modern Chinese write better histories than ancient Europeans? Hegel said that “no other people has had a series of historical writers succeeding one another in such close continuity as the Chinese.” In academia today students are being asked to “substitute a Europe-centered approach for a global approach” to correct a Western bias that assumed “that the Western style of historical writing is superior in everyway.” We now have books (such as “the impressive two-volume Global Encyclopedia of Historical Writing“) in which students learn how the historiography of Africa, Asia, and Latin America “rivals that of Western historiography.” The edited collection by historians from across the world, Turning Points in Historiography: A Cross Cultural Perspective (2002), cleverly tells us that history writing is not a “monopoly of the West…interest in the past appears to have existed everywhere and in all periods.” Are they serious that interest in the past can be equated with a tradition of history writing? Not quite, as the editors soon acknowledge (if implicitly) that “writing” has to be a key criteria: “it is well known that history and its writing did not begin in Greece” but “further to the east and earlier.” But this is not the contending issue either. Herodotus himself praised the Egyptians for “their practice of keeping records of the past.” It so happens that all the historians included in Turning Points in Historiography rely on what the book calls the “Western” scientific approach to history—rigorous use of sources and analytical precision—to make their case against “Europe-centered approaches.” None of these academics can undo the veracity that the Chinese tradition of history writing (deemed to be the only real competitor to the West) established in ancient times, the “annals-biographic form of dynastic historical writing,” with its moralistic tales as to “whether or not Tao was present in a certain period of history,” persisted with minimal changes for centuries right until Europeans brought their historical professionalism.

China is indeed the only civilization that can be said to have generated a continuous historiographical tradition, as Hegel understood. This same Hegel, however, would go on to say that it is nevertheless the case that their annals “fail to show any development.” In Turning Points in Historiography there are two very scholarly chapters seeking to show “new directions” in China. The first by T.H. Lee merely shows that in the period 960-1126 there was a “renewed” emphasis on moral teaching based on the reaffirmation of Confucian values, coupled with an increased emphasis on “historical criticism.” We are initially made to believe that this criticism amounted to rigorous questioning to determine the validity od the sources. But Lee, who supplies 89 bibliographic notes at the end of his chapter, soon admits, after a tortuous effort to show “new directions,” that “although Chinese historians were committed to recording historical events factually, they never developed a theory of historical criticism, at least until the end of the eighteenth century.”

The Greeks, Thucydides in particular, started historical criticism of sources, but it was really during the Renaissance that Europeans began to conduct a systematic study for the verification of sources. Lee admits, moreover, that Chinese history books in the period he examines “had yet to exhibit any tendency in employing causal interpretation” beyond showing an awareness that “events were related.” As much as Lee tries to bring Chinese historians closer to the standards of modern Western historiography, telling us that the Chinese understood that “when all the relevant facts are put together, and carefully collated and criticized…the truth will then reveal itself,” he cannot but conclude: “I admit that I have searched in vain for this analytical approach. The idea of causation, incipient as it was, did not continue to attract historical thinkers in imperial China; concern for supra-historical causes prevailed and overwhelmed the post Sung thinkers.” By “supra-historical causes” he means the ancient Chinese idea that history writing should be about the revelation of Tao in history, that is, with the didactic aim of showing that those dynasties that were successful had received the Mandate of Heaven, and those dynasties that were failures had lost the Mandate. The Chinese did not even develop a theory of dynastic cycles properly speaking, in the sense of identifying the causes for the rise and fall of dynasties, as the Romans did in identifying within human nature how the simplicity and frugality of early Rome had nurtured virtues that made its rise possible; and how the ease and affluence that came with successful conquests had nurtured vices that were leading to its decline.

Not even in the eighteenth century did the Chinese manage to transcend the Mandate of Heaven view of history. This can be established by examining the very words and conclusions of the second chapter in Turning Points in Historiography, which ostensibly seeks to demonstrate that China’s historiography underwent a major turning point in the 1700s, leading to a historiography comparable to that of the West during the Enlightenment. The title of this chapter, authored by the respected scholar Benjamin Ellman, is “The Historicization of Classical Learning in Ming-Ch’ing China.” In tedious detail, trying to squeeze every drop of evidence he can, with 113 bibliographical notes, but only barely filling a spoon, Elman concludes that by 1800 we see in China the use of “inductive methods by evidential scholars [that] indicated that they had rediscovered a rigorous methodology to apply to historiography” entailing “analysis of historical sources, correction of anachronisms, revision of texts.” Yet, he has to acknowledge, for otherwise he would have been dismissed as delusional, that this so-called “evidential research” of the Chinese “did not yet equal the ‘objective’ premises of German historicism” and that it only “resemble their European Enlightenment contemporaries.”

We will get to the Enlightenment and German historicism later on. Let it be said now that the “evidential research” of Chinese historians did not resemble the Enlightenment at all. Historians of the non-Western world like to give themselves airs about how they have deeper historical insights by implying that they know both Western and non-Western histories. In truth, their knowledge of the West rarely rises above generalizations bespeaking of their recollections of one or two undergrad surveys of European history. The “evidential research” of the Chinese had nothing to do with an emerging scientific attitude. To the contrary: it was an attempt to ensure a more accurate determination of the ancient Chinese classics as part of a revival of the authority of these texts in the name of a ritualistic conservative reaction. It was for the sake of ensuring the authenticity of ancient texts that Chinese historians cultivated a philological reading to determine which of many editions of the classics were really original and which copied or forged additions of later centuries. It is true that these “evidential” scholars were tired of the bookish Sung and Ming Neo-Confucians, their endless “rationalistic” commentaries on books, and thus they called for the study of “concrete subjects,” philology, history, astronomy, geography, and the like. But there was no resemblance between this and the Enlightenment, which, for starters, came in the heels of a Newtonian revolution, about which the Chinese had no idea.

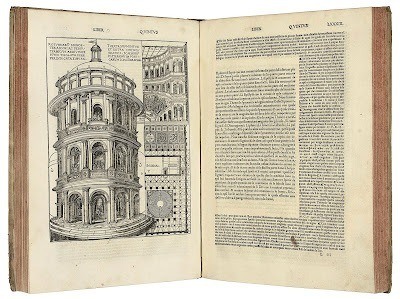

The Western-educated Chinese historian, Kai-wing Chow, questions the hyped up phrase “evidential research” in his book The Rise of Confucian Ritualism in Late Imperial China (1994), arguing that this period witnessed not a philological revolution but the “rise of Classicism, ritualism, and purism.” The “evidential” (k’ao-cheng) movement was a response to the threatened position of the Chinese gentry, an effort to restore an elite culture which had been considerably weakened by Ming commercialization. The vision of this movement was conservative, recovery of the “original” or “pure” Confucian norms and language. They were dedicated to philological precision in their efforts to achieve or recover the pure classical traditions. “Filial devotion, loyalty to the monarch, and wifely fidelity”—these were their mottoes combined with “punctilious observance of hierarchical relationship, and the exaltation of the ritual authority of the Classics.” As it is, the “philological revolution” Elman saw emerging in 17th–18th-century China had already been pioneered by 14th–century Italian humanists in their “rediscovery” of lost ancient Roman classics. Starting with Petrarch (1304–74), who discovered several texts of Cicero, including letters, and verified that these were actually written by him. Lorenzo Valla (1407–54) carried to maturity this philological program by developing sophisticated methods of linguistic analysis to determine age and authenticity. The best-known example of this textual analysis was his determination that the Donation of Constantine, a testament in which Constantine bequeathed his power and wealth to the Church, was actually a forgery.

Turning Points in Historiography has a chapter on the “ascendancy” and “inspirational” work of the contemporary Subaltern School of Indian historians—without asking why India, a civilization thousands of years old, never generated a historiography until Western historians brought their professionalism. The Times of India cited the following words from R. C. Majumdar, a highly respected historian of Indian history: “One of the gravest defects of Indian culture, which defies rational explanation, is the aversion of Indians to writing history. They applied themselves to all conceivable branches of literature and excelled in many of them, but they never seriously took to the writing of history, with the result that for a great deal of our knowledge of ancient Indian history we are indebted to foreigners.” The journalist who wrote this article went on to say: “For a country that claims to have a 5000-year-old civilization…There was little recording of the past, only a retelling and that too by poets who mixed fact with fiction and myth with reality.” In the words of Oswald Spengler: “in the Indian Culture we have the perfectly ahistoric soul.”