“Critique of Violence” (Zur Kritik der Gewalt) is notorious for its obscurity, which, at least partly, is due to the impossibility of translating several of the key terms used by Benjamin into English.

The immediate encapsulation of the task of a critique of violence conveyed in the German title and the first couple of sentences is entirely lost in the English translation. An etymological clarification is therefore important if we aspire to understand what a critique of violence consists of.

Critique (Kritik) should not primarily be understood as a negative evaluation or condemnation, but in the Kantian tradition of judgement, evaluation, and examination on the basis of means provided by the critique itself.

A more significant problem is however the translation of Gewalt—which in German carries the multiple meanings of (public) force, (legitimate) power, domination, authority and violence—with the English “violence” which carries few of these senses (particularly, institutional relations of power, force and domination or even non-physical or ‘symbolic’ violence).

That the task of a critique of violence is to be understood as expounding the relationship of violence (Gewalt) to law (Recht) and justice (Gerechtigkeit), is thus much less artificial and obscure.

Two further etymological clarifications are however necessary to fully understand the task of Zur Kritik der Gewalt. Recht, as the Latin Ius, carries the meaning of both rights and law (as in the general system of laws), which is juxtaposed to specific laws, Gesetz corresponding to the Latin Lex. Sittliche verhältnisse, translated to “moral relations,” presents a more significant problem in terms of translation.

In English it is not immediately clear why the sphere of law and justice can be understood as the sphere of moral relations. Morality carries the Kantian tradition of an abstract universal law (Moralität) in English, than the Hegelian tradition (Sittlichkeit). In Philosophie des Rechts, Sittlichkeit is the term used for the political framework of ethical life, that is, the family, civil society and the state.

Violence is thus to be critiqued on basis of its relations to law and rights within the framework of ethical life in the state (sittliche Verhältnisse). For a cause” Benjamin writes “becomes violent, in the precise sense of the word, when it enters into moral relations.”

Benjamin is thus not interested in force or violence of nature (Naturgewalt); but the violence present within the framework of the society, and ultimately, the state.

The critique of violence can only be undertaken through the philosophy of the history of violence (or we might add, in a “deconstruction” of the philosophy of the history of violence), Benjamin argues. In his “deconstruction” of the relationship between violence, law and justice, Benjamin erects several pairs of opposition.

However, as Derrida pointed out, many of these deconstruct themselves. The first such pair of oppositions is natural law (Naturrechts) and positive law (positive Rechts), which even though they in general are understood as antithetical (natural law is concerned with the justice of ends, positive law is concerned with the justification of means) share a fundamental dogma, namely that a relationship of justification exists between means and ends.

For this reason, the two theories agree that violence as a means can be justified if it is in accordance with the law. Benjamin raises the following objections against this dogma: if the relation of justification between means and ends is presupposed, it is not possible to raise a critique of violence eo ipso but only applications of violence.

Hereby, the question of whetherviolence in principle can be a moral means even to a just end is made impossible to address. By insisting on critiquing violence in itself, Benjamin challenges the fundamental dogma of jurisprudence, namely, that justice can be attained if means and ends are balanced, that is, if justified means are used for just ends.

The question, thus, is how violence and law relate to one another? Benjamin argues that the intimate relationship of violence and law is twofold. Firstly, violence is the means by which law is instituted and preserved. Secondly, domination (violence under the name of power (Macht)) is the end of the law: “Law-making is power-making, assumption of power, and to that extent an immediate manifestation of violence.”

Benjamin distinguishes between lawmaking violence (rechtsetzend Gewalt) and law-preserving violence (rechtserhaltende Gewalt) on basis of whether the end towards which violence is used as a means is historically acknowledged, i.e., “sanctioned” or “unsanctioned” violence (named respectively “legal ends” and “natural ends”).

If violence as a means is directed towards natural ends—as in the case of interstate war where one or more states use violence to ignore historically acknowledged laws such as borders—the violence will be lawmaking. This violence strives towards a “peace ceremony” that will constitute a new historically acknowledged law; new historically acknowledged borders.

The establishment of borders after a war is a clear example of the institutionalisation of a relation of domination inherent in all lawmaking violence. In guise of equality before the law, the peace ceremony is a manifestation of violence in the name of power; “in a demonically ambiguous way,” Benjamin writes, the rights are “‘equal’ rights: for both parties to the treaty, it is the same line that may not be crossed.”

This demonically ambiguous equality of the law, Benjamin writes, is analogous to that which Anatole France satirically expressed when he said: “Rich and poor are equally forbidden to spend the night under the bridges.”

In contrast hereto, if violence as a means directed towards legal ends—exemplified by compulsory general conscription where the state forces the citizens to risk their lives to protect the state—the violence will be law-preserving.

The distinction between lawmaking violence and law-preserving violence is however deconstructed in the body of the police and in capital punishment, whereby the “rotten” core of the law is revealed, namely, that law is a manifestation of violent domination for its own sake. In both capital punishment and police violence the distinction between lawmaking and law-preserving violence is suspended.

Capital punishment is not merely a punishment for a crime but the establishment of a new law; police violence, though law-preserving can for “security reasons” intervene where no legal situation exists whereby the police institute new laws through decrees. In capital punishment and police violence alike, the state reaffirms itself: law is an immediate manifestation of violence or force and the end of the law is the law itself.

This violence of the law—the oscillation between lawmaking and law-preserving violence visible in police violence—is explained by Benjamin with reference to the Greek myth of Niobe.

Niobe’s boastful arrogance towards Leto—she having fourteen children and Leto only two—challenges “fate,” (Schicksal). The never defined concept of “fate” seems to refer to a relation of power (Macht). What Niobe challenges is not the law, but the authority or the legitimate power of Leto. When Apollo and Artemis kill her sons and daughters, it is thus not a punishment but the establishment of a law (“neue Recht zu statuiren”).

Niobe is turned into a crying stone (a statue) which is a physical manifestation of the law (the statute) as the power of the gods instituting “a boundary stone on the frontier between men and gods.” For this reason, Benjamin writes, power (Macht) is “the principle of all mythic lawmaking.”

Having now expounded the relation between law and violence, the question of the relationship between law and justice can be raised. Benjamin is not only speaking in metaphors when he writes: “Justice is the principle of all divine end-making, power the principle of all mythic lawmaking.”

Justice is an end which in principle cannot be reached within the realm of law: justice belongs to the realm of religion and it is not something we can obtain deliberately through law or reason: “For it is never reason that decides on the justification of means and the justness of ends: fate-imposed violence decides on the former, and God on the latter.”

Benjamin is however fundamentally interested in justice; Zur Kritik der Gewalt is the closest we get to a Benjaminian “theory of justice”. The impossibility of justice within the immediate manifestation of violence/force in the mythic “power-making” of law makes the destruction of law in principle “obligatory.”

The political general strike that merely aims at a coup d’état is therefore insufficient; the “force of law” can only be overcome if law in principle, and hereby state power as such, is destroyed. What is called for is therefore a proletarian general strike that aims at the destruction of all state power.

A paradoxical perspective in Benjamin’s text is that even though justice is transcendent (it is God who decides upon the justness of ends) it does not mean that human actions cannot be an expression of divine justice. The problem, as Derrida saw, is that we can never know whether actions have been a manifestation of divine violence.

Justice is possible (but not knowable)through an act of divine violence, which in all respects stands in complete opposition to the mythic violence of law: “If mythic violence is lawmaking, divine violence is law-destroying; if the former sets boundaries, the latter boundlessly destroys them; if mythic violence brings at once guilt and retribution, divine power only expiates; if the former threatens, the latter strikes; if the former is bloody, the latter is lethal without spilling blood.”

Divine violence is exemplified by God’s judgement on the company of Korah, who without warning or threat and without bloodshed is annihilated by God: the earth opens beneath them, swallows them, and closes again without leaving any mark.

In contrast to mythic violence, divine violence does not aspire to institute as law a relation of domination: divine violence accepts sacrifice. This is not sacrifice for its own sake like the murder of Niobe’s children, but “for the sake of the living” (the company of Korah is annihilated not for the sake of God but for the sake of those who are spared). “In annihilating” Benjamin writes, divine violence “also expiates” (entsühnend); it is however not the “guilt” (Schuld) that is atoned for by the divine violence; divine violence purifies the guilty, not of their guilt but of the law.

How can we understand the purification of the guilty of the law by divine violence? What is “pure” (rein) about divine violence (die göttliche reine Gewalt)? The German rein as the English pure carries the double meaning of something clean, and something absolute and unalloyed.

Firstly, divine violence is pure (meaning clean) because it has not been bastardized with law; it is pure as before the fall of man; it is pure from the guilt of the law (the guilt Niobe feels for the death of her children). Secondly, divine violence is “pure” (meaning absolute or unalloyed) because of the way it relates as a means towards an end.

Where mythic legal violence does not differentiate between mediate violence (violence as a means towards and end) and immediate violence (a manifestation of anger, or a relation of domination), divine violence is “pure” and immediate because it puts forward independent criteria for means and ends.

Where mythic violence conflates means and ends, divine violence separates means and ends. As Benjamin argues, just ends can only be decided by God, and no law can be given for justified means; what we have is only a guideline (Richtschnur).

The sixth commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” is an example of such a guideline. Benjamin’s use of the word Richtschnur is very telling in this context: “Thou shalt not kill” is exactly not a law (Recht) but a guideline (Richt-schnur). A Richtschnur (which in German also is known as a Maurerschnur) is a mason’s line: a string (schnur) which is used to measure or correct (richten) out a plane for a building by the masons or bricklayers.

A Richtschnur is an approximation used practically to build a house. To build a good house the masons, in general, would have to follow this Richschnur but sometimes, because of a broken ground, a good house could only be built if the Richtschnur is ignored.

By substituting law (Recht) with the almost homophone Richt, Benjamin establishes the fundamental difference between mythic power (mytische Gewalt) and divine power (göttliche Gewalt). The commandment is not law but a guideline which in general would have to be followed for human beings to live a good life, as the masons in general have to follow it to build a good house. There might however be situations where it would have to be ignored.

Neither is the commandment law in the sense that a judgment of an act that ignores the guideline can be derived from the commandment: “No judgment of the deed can be derived from the commandment,” Benjamin argues “and so neither the divine judgement nor the grounds for this judgment can be known in advance.

Those who base a condemnation of all violent killing of one person by another are therefore mistaken.” This misunderstanding has to do with the general misunderstanding, argues Benjamin, that just ends can be the “ends of a possible law.” This misunderstanding is grounded in the belief that just ends are capable of “generalization,” that it, in other words, is possible a priori to discriminate between right and wrong.

This “contradicts the nature of justice,” Benjamin argues, “for ends that in one situation are just, universally acceptable, and valid are so in no other situation, no matter how similar the situations may be in other respects.” For this reason, no law can incapsulate justice.

The only thing we have is the “educative power” (erziehriches Gewalt) of the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” which can educate us how to live a good life in the same way the masons can learn from their Richtschnur. The commandment “exists not as a criterion of judgement, but as a guideline for the actions of persons or communities who have to wrestle with it in solitude and, in exceptional cases, to take on themselves the responsibility of ignoring it.”

What are these exceptional circumstances? For Benjamin, the decayed mythic violence of the law of the modern state seems to make up such exceptional circumstances: the destruction of all legal violence and the state becomes an “obligatory” task for the pure immediate violence; divine violence.

The proletarian general strike and the abolishment of state power which constitutes a break with the oscillation between lawmaking and law-preserving violence will lead to a foundation of a new historical epoch (neues geschichtliches Zeitalter).

Here, we see why Derrida summarizes Benjamin’s position as “messianico-marxist or archeo-eschatological” (Derrida, Force of Law). The Critique of Violence is Benjamin’s political demand for a revolution: “the existence of violence outside the law, as pure immediate violence,” Benjamin writes, “furnishes proof that revolutionary violence, the highest manifestation of unalloyed violence by man, is possible, and shows by what means.”

Benjamin is “messianico-marxist” in that he argues that divine violence signals the coming of the Messiah in form of the revolutionary general strike which will bring a new historical epoch.

He is “archeo-escatological” in that he argues that the eschatology of the revolutionary general strike, manifested in the true war (wahrend Kriege) or the multitude’s Last Judgement on the criminal (Gottesgericht der Menge am Verbrecher).

The multitude’s judgment on the state, will “expiate” the crimes committed by the mythic violence of law and return us to the time before the decay (Verfall) of the law: “Once again all the eternal forms are open to pure divine violence, which myth bastardized with law.”

In Benjamin’s final condemnation of mythic violence, the Judaeo-Christian connotations become apparent: “Verwerflich aber is alle mythische Gewalt.” Verwerflich meaning unrighteous, something that has to be condemned, comes from the verb Verwerfen, to dismiss or to abolish, which again comes from the verb werfen meaning to throw: the law is thus as the Fall of man: an unrighteous and condemnable (Verwerflich) deed that has dismissed (verwerfen) the guilty from Paradise.

Divine violence, however, has the power to purify the guilty of the law. In this way, Benjamin calls for a revolution, which also carries the original astronomical meaning of the completion of a cycle: the revolution which constitutes a new historical era will return human kind to the time before divine power was bastardized with law; in a word “archeo-eschatology.”

Signe Larsen main interest lies within political theory and philosophy of law.

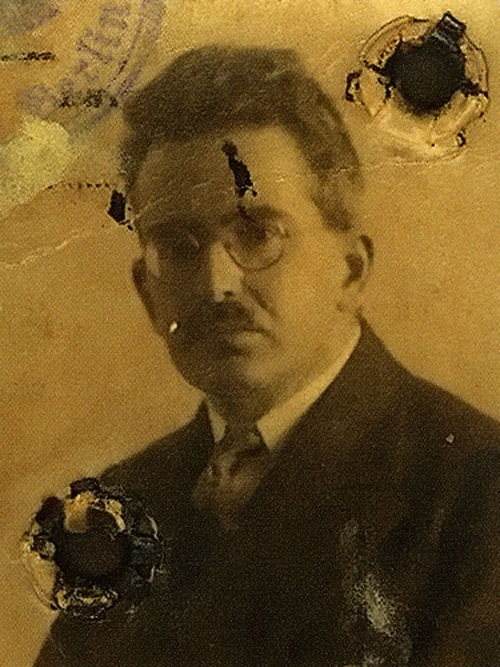

The photo shows Walter Benjamin’s passport photo, ca., 1928.