Critical thinking is simply a bad label for practical wisdom. What gets taught as “critical thinking” has nothing to with thinking, life, let alone wisdom.

In other words, “critical thinking” is simply an invention of the education-industry to further enslave students’ minds (but that’s another topic).

Wisdom is even buried in the very root of the word “critical,” which derives from the Greek verb krinein, “to decide,” or “to judge.” Neither process is possible without wisdom, which is knowledgeable discernment.

To have the ability to judge or decide is not a skill – it is process of reflection, which in its root sense means, “to turn back” one’s thoughts and consider closely.

Practical wisdom, then, is to turn back and rediscover the habit of looking for meaning, value and for truth. Since humans are social creatures, we already possess the ability to think this way.

Only ideology makes us forget to follow our proper and true mental inclinations.

But given the way the educational system functions, ideals are never emphasized.

Practical wisdom is also “humanistic thinking,” which is concerned with the moral improvement of the individual and then, by extension, of society.

How can we rediscover the habit of practical wisdom? We can do so, by focusing on those aspects of our cognition that skill denies, such as, doubt, questions, ideals, symbolic thinking, the imagination, harmony, and moral judgment.

When we look for meaning and value, we begin with doubt, with hesitation, with being unsure, because we have to decide between two or even more possibilities.

Doubt gives us pause, which we often need in order to think things though.

There are two important characteristics of doubt: skepticism, which is a state of disbelief but also an invitation to view an idea or proposition carefully; and wonder, for we ask, how can this be?

Doubt is the very beginning of reflection, of turning thoughts over in our minds, because doubt allows the mind to open up to possibilities unknown.

Doubt breaks down the barriers of assumptions and launches us into the process of building anew. We must be courageous doubters in order to search for value and meaning.

Once doubt pervades the mind, we begin to ask questions. Most people fear questions because nothing uncovers ignorance (a state of mindlessness) faster than a question.

When we ask questions, we are not looking for answers but seeking, inquiring after, the truth (which is faithfulness to reality, both material and ideal).

As a result, there is a strong link between questions and freedom, because only people who are truly free can ask questions; those enslaved in any sense cannot ask questions, because questions have the potential of destabilizing the status quo.

Thus, questions are a threat to those in power. And as for enslavement, it comes in many forms – the most pervasive in our culture is the avoidance of complexity. We want everything to be simple.

And here is a strange conundrum: we live in a world that is highly complex and the technology we use daily is highly complex – and yet we put this complexity to simpler and simpler uses, such as language pared down to is bare minimum, as in a text-message. We all have skill with technology – but we are therefore thinking less and less with language.

Here’s an important question to ask – does a good worker need to doubt and ask questions? Or does a good worker simply need to employ skill and expertise? If we cannot formulate questions, are we truly free?

If we accept that questions are an inquiry into truth, then we are led into asking a rather famous question – what is truth?

In effect, truth is an ideal. It is not a material thing, but it is something that humanity greatly values.

An ideal is an idea that possesses value and meaning. There is no human culture which does not value truth.

Of course, there have been many attacks on the notion of truth – that it is a cultural construct, or that it is closely connected to individuality (hence the term, “truth is relative”).

We’re all familiar with the usual dull arguments – since we all have different ideas of what truth is, there is no universal definition of truth; and so every culture in the world creates its own truth; my truth cannot be your truth – and some people even more radically suggest that there is no truth; or put more bluntly, truth is only a matter of personal opinion. So, if truth does not exist, why bother looking for it?

Ultimately, these are dead-end arguments since they do nothing to advance thinking, nor do they help us to understand why the search for truth is essential to practical wisdom.

Briefly, to say that there is no such thing as truth, or that truth is relative, is a contradiction since we are being told that both these statements are indeed true – and should be universally believed, which makes no sense at all. How can anyone suggest that there is no truth and then expect us to take this statement as the truth?

We have only to look at the world around us – and we find that humanity continues to conduct itself with the idea of truth – people in all cultures want to be right and not wrong, they want to be good and not bad.

Truth should not be confused with belief (which can be personal) – we may believe one thing at one time in our lives and then come to believe something completely different later on in our lives.

For example, Nazi Germany believed in murdering Jews. Modern Germany does not believe this. Beliefs change – truth does not, because it is an ideal. So, in our example, the truth remains the same – murder is wrong.

We may misunderstand an ideal or misinterpret it, but truth does not change. This unchanging quality makes it an ideal. Ideals help us to choose and decide how we want to live our lives.

Ideals are intangible structures, blueprints, with which we derive meaning and value. Why do we feel good when we do good things? And why are we riddled with guilt when we do bad things? Why do we want to love and be loved? Why are we sympathetic?

These are all questions of ideals, of truth, of value, of meaning. Through ideals, we become educated in our goodness. And the truth is – we want to be good. Think of it – all those things that we cherish (love, kindness, hope, goodness, decency, etc.) are ideals.

When we say ideals are examples, we have begun to think symbolically. What does this mean? Simply that we get into the habit of looking for ideals by way of symbols, that is, examples. Light is a symbol for truth and goodness; its opposite, darkness, is a symbol for falsehood and evil.

Symbols give us something concrete, something material, which we can use to start thinking of an ideal (value and meaning), which cannot take on physical form.

The world over, water is symbol of life – and is it any wonder, therefore, that scientists looking for life on Mars are looking for water? The search for life in outer space is both symbolic and ideal.

We know there is life on the planet earth; and since there are planets in our solar system and in space, we have made terrestrial life into an ideal, assuming that life requires certain properties in order to exist – and it is this ideal that scientists search for.

But to think symbolically also means that we have to be imaginative. Imagination is the ability to see relationships between things and between ideas.

To use the imagination is to see the underlying truth of things. Thus, for example, to want freedom is an imaginative act, because it is insight into what we really value and what gives us meaning.

Freedom is a particular kind of relationship between the individual and society. To want freedom means that we see the essential purpose of life – to have freedom is to live as we see fit – and it also means that we see the truth of what it means to be alive.

Symbolic thinking is the process of uniting ourselves with ideals. Freedom is an ideal – and we individually unite ourselves to this ideal way of living: We want to be free.

Closely allied to symbolic thinking is the concept of harmony, which is the ability to see relationships even in things and ideas that may seem at first to be diametrically opposed to one another.

In other words, it is the ability to see how things and ideas fit together. All too often thinking involves an agonistic attitude – ideas need to be “argued (demonstrated)” or even “attacked,” and “defended.”

To look for harmony is a crucial aspect of practical wisdom, since a habit of seeking convergence and relationships advances thought, which means that relationships engender newer ideas.

These various aspects of practical wisdom are dependent upon the reason why we need to think in the first place.

Practical wisdom is about forming moral judgments that provide us with value and meaning, both of which suggest that we want to understand how we ought to live and what we ought to do.

Practical wisdom is about educating our moral character, through which we can discover how we ought to live in order to be good in a good society, and what we must do to be good in a good society.

Thinking, therefore, is never done in a vacuum. Thinking is always about context – and humanity’s context is the world.

And what is the world? It is the construct in which we live our lives – and as such, it is ideas placed upon the physicality of the planet earth to make our lives happy and fulfilling and to allow each of us to understand what gives us meaning and value.

Let us now start the process of rediscovery and come to understand what we ought to do to gain and possess practical wisdom so that we may know how we ought to live and what we ought to do in the good society.

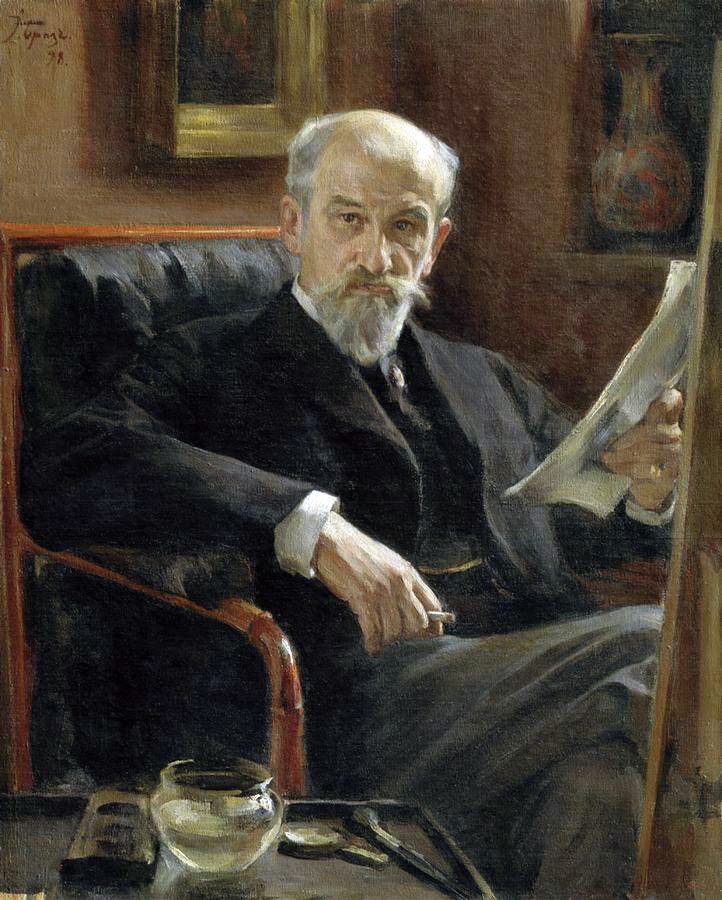

The photo shows, “Portrait of the Artist Alexander Sokolov,” painted by Osip Braz, in 1898.