1. Polish Peskiness Brought Down the Soviet Union, While The Soviets Transferred The Baton Of Imbecility To Educated Westerners

Is it the Bigos (hunter’s stew), is it the Zurek, is it the Blintzes, is it the Pierogi, or the Krupnik which makes the Poles so damned obstinate, so pesky?

Or is that a people, whose nobles went against the current in the sixteenth century by devising a noble system of democracy (an elected monarch with a functioning parliamentary legislature) when other European countries were becoming increasingly absolutist, really don’t like being bossed around by bumptious authoritarian idiots?

Or is that a people who were written off the map for more than a hundred years don’t like being written off or out of history, and that a people who fought and successfully defended themselves against the Bolsheviks in 1919-21, only to be invaded by the Soviets and Nazis, don’t like being victims of the deranged imperial dreams of others?

Or is it that a people who were duped into becoming a communist country and Soviet vassal have inoculated themselves against being duped again by ideas that promise to be very heaven but turn out to be hell?

Or is that a country whose Catholic identity was just too strong for the communists to successfully suppress continue to hang onto their religious identity when Western Europeans view their own history, and religious heritage, with a mixture of ignorance and shame (unfortunately without being ashamed of their own ignorance)? One Polish refugee from communism, Aleksander Wat, in My Century, thought that

“Poland’s mainstay was not in revolts but in “disengaging from the enemy,” specifically, the country’s overwhelming Catholicism, precisely that parochial, obscurantist, and often vulgar Polish Catholicism, which, however, purified itself and grew deeper “in the catacombs” and truly found its shepherd in the person of the Primate, Cardinal Wyszyński. That Catholicism made the Polish soul impervious to the magic of “ideology” and the knout of praxis, and it was not the rebellious writers and revisionists who caused the Polish October but – apart from Stalinism’s crumbling power and cohesiveness – the steadfast, constant, unyielding mental resistance of that Catholic nation, its “dwelling” in transcendence.”

Whatever it is, though, those Poles sure are pesky for anyone who thinks they should roll over and take a boot on their necks. They probably vote in such large numbers for the Conservative Law and Justice party just to give the finger to the Western Europeans elites who all want the Poles to come to their party of endless progress – and self-annihilation.

In the upside-down world represented by the European Union and mainstream Western European political parties, it is authoritarian to oppose dismantling the values of Christendom which gave the West its greatest achievements. Likewise, West European elites cannot stand the fact that a predominantly Catholic country has the temerity to want to defend its Catholic tradition from a group who might be more smiley than the previous Soviet bullies, and who generally tend to like to get their way with promises of giving or withholding large pots of money rather than bringing in tanks. But the pesky Poles wipe off their smiles and make them hot under the collar when they say thanks for the money and trade deals, but no thanks to the tactic of welcoming Muslim migrants and refugees to transplant not only themselves in their flight from economic and political hardship but their traditions and, in too many cases, their pan-Islamist aspirations on a remaining national bastion of Christian soil. The Western European elite wants all opposition to its values and institutional overhauling to fold in exactly the same way as they themselves are folding to their geopolitical enemies. They seem to struggle to understand why a country, whose workers openly took to the streets against the communists in 1956 and then again from 1980 formed the union, Solidarity, to defy, with eventual success, their Soviet masters, won’t simply take the money and obey. Why they think they will succeed where the Soviets failed is but one more example of how all the mountains of bureaucratic EU drivel is a cipher of mental vacuity, merrily redesigning the world in the image of its own emptiness – the confirmation, if one will, of an intelligentsia which once spawned, Being and Nothingness, merely becoming nothingness. And whereas the Western elites, like their US counterparts, all accepted the eternally enduring presence of the Soviets, the Poles became the spearhead of what would ultimately inspire others from Soviet satellite countries to also stand up to their Soviet masters.

Yes, there were many things that bought about the demise of the Soviet Union, from a disastrous war in Afghanistan to a nuclear power plant accident, which revealed the dangerous incompetence of trying to preside over nuclear power with a system in which raw power and ideology always trumped over truth and competence, to a US president, depicted by the intelligentsia as a cross between Bozo the clown and a third rate actor who thought he was a cowboy, who defied the conventional wisdom – that the Soviet Union was an undefeatable superpower – by upping the arms race to levels which bought an already ailing economy and a gerontocratic power, loosening its grip through age and a generational power transfer, to its knees.

But one could not underestimate the peskiness of the Poles when it came to the fall of communism. There was the outspoken and very pesky Polish Pope who had inspired the formation of Solidarity, and who refused to go along with the rot in the Church that was all for Christian Marxist/communist dialogue, and liberation theology, itself little more than a Soviet propaganda front posing as Christian teaching. And then there was the pesky Polish priest who was closely connected with Solidarity, Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, who was murdered by members of the security service. His murder only served to ensure that Solidarity would be an even bigger thorn in the side of the communist government than it had been before.

Generally, though, it is the sad fact that when the Soviets were well on the way to losing the military war, they were already defeating the West in the propaganda war. Their victory was pyrrhic because their attempts at open-ness and reform proved to be as disastrous as the rest of their attempts to realize the dreams of a bunch of ideas spearheaded by people who thought their knowledge and philosophy could create a system that was both perfect and unprecedented. All that was left was to leave their communist allies presiding over their satellite dependencies in the lurch, and walk away from a political system that was taped together by lies and people spying on each other, and an economic system that could not produce enough bread, let alone computerised arms systems to rival the US. (Whether to their credit or not remains to be seen, but the Chinese had already decided to drop the economic system while holding onto the political system). So, the Soviets had a bargain basement jumble sale where Western grifters and con-men like William Browder, the grandson of the American communist party leader Earl Browder, and the local mafia scooped up the assets of a country.

And while almost all the Soviet scholars went over night from being media talking heads and clueless political scientists explaining why détente was a very good deal, to historians scratching their heads over why the biggest event since the Second World War took place without them having a clue it was coming – that wannabe American cowboy Bozo and a handful of his anti-Soviet advisors, who had been reading a few astute economists who had identified the gigantic budgetary hole covered by creative accounting, which involved simply transferring next year’s income to this year’s, who saw what the Poles saw – that Soviet power was just one more in a long line of heavily guarded Potemkin villages.

Though to be fair to the smarts of the Soviets, while they could not run a country, they sure knew how to dupe the minds of Westerners. For just as from the time of Lenin’s take-over to Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, the Soviets had managed to convince many of the leading minds of the intelligentsia in North and South America, Western Europe and Australasia about the virtues of Soviet communism, up until its demise, the Soviets had created all the key critical phrases and “talking points” that radicals of the 1970s and 1980s would use when it came to the power politics of the Cold War. They would all castigate Regan as a warmonger for calling the Soviet Union an evil empire, for devising a bomb that would kill people without destroying buildings, for walking back on détente and upping the arms race, and for having the temerity to plan a missile shield system that was thereby, according to the radicals and Soviets, increasing the likelihood of nuclear war, even though, they would add, with absolute assuredness and without a blink, it was a scientific impossibility. The dialectic of imbecility had already been a successful experiment, conducted by the Soviets upon the better educated saps in the West.

For anyone who can recall, the media reported almost daily on the well-meaning protesters in Western Europe wearing gum boots, rainbow dyed tee-shirts, peace signs and carrying their kiddies on their shoulders – while on MTV, Sting, like so many singers who believe that being able to knock out a good tune gives them a terrific handle on geopolitics and how to achieve world peace, having taken time off from saving the Amazon, was earnestly intoning: “If the Russians love their children too/ How can I save my little boy from Oppenheimer’s deadly toy?? (Allow me to put it on the public record, so that on Judgment Day I can say in my own defense – for all my sins, Lord, no matter how hummable his tunes, I could never stand the sanctimonious strains of Sting.) All their anti-nuclear protests were directed at weakening military opposition against the Soviets – for, they intoned repeatedly, it was NOT the Soviets, but the USA who was bringing the world to the brink of destruction. This was of course before the next (pre-COVID) all-encompassing catastrophe – global warming/climate change, which would push aside nuclear disarmament as the source of hyperbolic panic requiring an elite of wise and all-knowing saviours.

The most radical Westerners thought they were super smart in being non-Stalinist, non-Soviet Marxists. But they were to use the phrase coined by the pesky (Lithuanian born) Pole, Czeslaw Milosz, “captive minds.” This is perhaps why, in spite of not being attracted to the grey lump that the Soviets had served up as communism, Western radical students could not tolerate Soviet dissidents being given any kind of platform. I was studying in West Germany in 1984 and recall a poorly attended talk by a Soviet dissident. The West German university students booed him for being a US Cold War stooge.

Today the tactics and narratives that the Soviets had fostered long before the Cold War in creating disunity in the USA by fueling racial strife so it becomes a civil war, are now not only commonplace in universities and schools but in corporations and the White House itself, which approves of critical race theory being taught even in the military. The communist strategy of subversion was all mapped out in detail by the KGB defector Yuri Besmenov, and his book, Love Letter to America, written under the pseudonym Thomas Schuman. But his warning was already a generation too late – at the moment, the US was poised to win the Cold War, it had lost its mind (its universities, its media, Hollywood and other idea-brokering institutions) to the same terrible ideas that the Poles and others were trying to shake off.

The legacy of the communist victory – leaving China alone to pick up the spoils – is now so obvious, that half the US sees it. And it is certainly not those US citizens who control the formation and circulatory flow of the ideas of the ruling class. It is also significant that two of the best recent books that are diagnosing the spiritual, intellectual and social suicide of the Western world are by Poles, Ryszard Legutko, and Zbigniew Janowski. The former is a member of the European Parliament as well as the author of The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies, and more recently, The Cunning of Freedom: Saving the Self in an Age of False Idols.

Legutko came to prominence a couple of years ago thanks to the stupidity and bellicosity of students and staff at Middlebury who, having slapped up posters and a Facebook page denouncing Legutko as a “f****ing homophobe and sexist,” prevented him from speaking about the dangers of totalitarian democracy engulfing “free societies.” The public talk having been cancelled, the professor who invited Legutko to the college had his nine students hold a secret ballot (yes, this is how free students are today in an American university) to see whether Legutko should give the intended lecture to them.

They voted yes (sanity prevailed for a moment), and he did manage to commence his lecture to the professor’s small class. But as more students filed in and word got out, that too was subverted and Professor Legutko was escorted off campus. I doubt if any of the staff or students had the wherewithal to even read his book, let alone ask whether their confirmation of the “thesis” of Legutko’s book was really making a better world. They were just like anti-Semitic Christians, who never understood that their tactics only served to illustrate the deficiencies of their own personal faith, character, and behaviour. Unfortunately, the world is made more by the deficiencies of who and what we are and do than by the neatness of our (ostensible) moral reasons and ideas. But good luck finding twenty professors in the USA who know or care about that.

Just as some Muslims kill people to protest against those who publicly dispute that Islam is a religion of peace by referring to violent imperatives in passages of the Koran and hadith, elite students and academicians of today want to end hate, serve social justice and overcome all oppression by screaming at and shutting down anyone who thinks that they are just a bunch of bullies, know-it-alls, and spoilt brats, who know nothing serious about society or even justice. Though there are spoiled brats in Poland (and members of its intelligentsia) who also want to join the mental and spiritual suicide being undertaken by their Western counterparts, and whom the Western elites are recruiting into its ranks.

Hence a group of them, who had sought to enforce a ruling of the European Court of Human Right’s work that proscribed all religious symbolism from schools, also hauled Legutko before a District Court in Kraków. His crime? Apparently, it was calling them “spoiled little brats.” Sadly, just last month, Legutko found himself attacked again by students and members of the Philosophy Department of the Jagiellonian University, where Legutko teaches.

The reason for this was his letter to the university Rector about the dangers of the university having put in place a Western style administrative department for equity grievances. The letters – which are appearing in the Postil – illustrate the same pathetic and sanctimonious reasoning, self-serving moral platitudes, and appeal to authority as are found today in every Western university – confirming yet again that philosophers are not inoculated against being seduced by their own moral vanity, and are no more inclined than anyone else to take on the burden of historical memory, when required to think for a moment about what ethically fragile and generally unwise creatures, such as we do with the machinery of abstractions, once it is set up to ensure social control.

Janowksi, like Legutko, grew up under communism, but he returned to Poland last year, after thirty-five years in the USA. From my correspondence with him, Janowski is a born teacher, and it seems that he found many US students who greatly appreciated what he had to teach. But he was worn down by the mental midget-ism and wokeness that had taken over the university, along with the university administration who would periodically carpet him for his contrarianism.

As anyone who knows the least thing about Western universities today, university administrators have mastered the racket of having students and the state pay their exorbitant salaries, while simultaneously shutting down, and clearing out all genuine intellectual work in the Arts and Humanities, and while creating the safe spaces so their students learn that all whites are racists and that the USA is the most racist country in history.

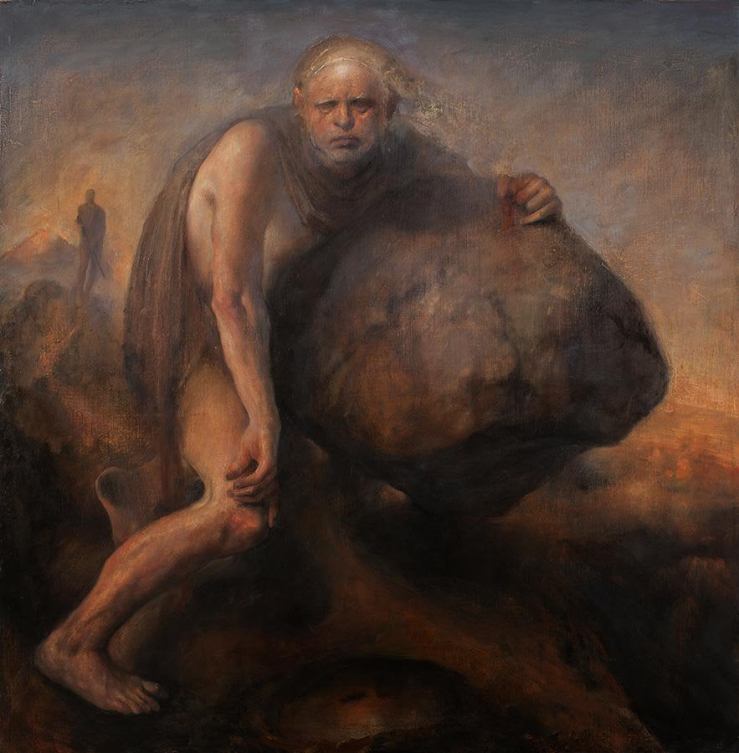

Janowski has captured this farcical replay of totalitarianism in the USA (if I may borrow Marx’s tweaking of Hegel on history) in his excellent book, Homo Americanus: The Rise of Totalitarian Democracy in America. But before looking more closely at the works by Legutko and Janowski, I want to briefly discuss that earlier generation of pesky Poles who were trying to bring down communist totalitarianism – one of them, Leszek Kolakowski, was Janowski’s PhD supervisor, and hence a direct source of inspiration for him.

2. Poles Against Communist Totalitarianism

While there is a very long list of Polish critics of communism, I suspect that the two most well-known to Western readers are Leszek Kolakowski and Czeslaw Milosz, the former a philosopher, the later a poet. Given that communism is a poetic fabrication, resting upon a metaphysical contrivance, it is fitting that philosophers and poets expose its centre as being nothing more than thoughtless and abstract words; that is, words that are void of the sediments of soul that good poets are attuned to access, or the conceptual sharpness that provides philosophical insight into our actions and the world.

The central feature of Milosz’s Captive Mind, written in 1951, when the young Kolakowski was still a believer in communism, is its depiction of poets and writers whose love of words and art eventually lead them all to betray their muse as they (for diverse reasons from their own ideological need to believe, and their self-induced blindness to economic and political opportunity to fear) succumb to mental captivity.

In Milosz’ own case, we are not dealing with a particularly political animal, even though the Captive Mind provides some valuable reflections upon how the ideology of communism and its “philosophy” of dialectical materialism kills the spirit. Milosz, though, was a man who could distinguish between what is truly venerable in poetry, and hence why commitment to it cannot be compromised by ideological fiat, and vacuous verbosity.

The cross roads that placed Milosz between the choices of following the power and opportunities that came from using his pen in the service of power or keeping true to the muse, was very similar to Kolakowski – who might have been an ideological hack had philosophy not remained his true love. And it was also his love of philosophy that enabled him to see the sheer untruth of the endeavour he was devoting his faith to.

Communism is a jealous God, and it is a philosophical God that requires total metaphysical possession of the mind (to be sure it is also a crippled philosophical God demanding crippled minds). Its claim to possess the scientific method, dialectical (historical) materialism, to enable its practitioners to identify the objective laws of history, and the larger historical meaning of the political and economic circumstances of the hour, is a big claim that reality rebukes at every opportunity.

Kolakowski had a keen metaphysical sense and that sense runs through his philosophical writings where the “big questions” remained his philosophical preoccupation until his death. Back in the 1950s, it was becoming clear to Kolakowski that dialectical materialism was a very small – and ultimately paltry – box of mental tricks when it came to dealing with the “big questions” that required really using the powers of the mind.

In some ways, communism was always about one’s mental powers, whether one really wanted to develop them, or whether one was happy to learn and apply a philosophical dogma and defend it at all costs. Marx would always resort to invective when anyone disagreed with him; and in that respect, he set the precedent of what one had to do – bully, threaten and silence one’s opponents – if one wanted to protect a set of doctrinal principles and commitments – the method of dialectical materialism – from philosophical critique.

Thus it was that Lenin, who had read very little philosophy, took time away from his revolutionary screeds and tactical writings to study Hegel’s Science of Logic (and just in case anyone might think he was not serious, it was not the shorter Logic of the Encyclopedia but the big thick one!) – the study remains clear for all and sundry to read thanks to his disciples preserving his notebooks as if they were holy writ.

The “study” is mostly transcription, and gloss with comments and marginal scribblings – all of which confirm that Lenin was completely clueless about what Hegel’s philosophy was. Thus like a deranged school master after all the screaming and dribbling (“Hegel conceals the weakness of idealism;” “ha-ha he’s afraid! Slander against materialism Why??”), he also found things in Hegel he could give big ticks to (“excellent!” “subtle and profound!” “a germ of historical materialism,” and such like).

Lenin already knew that history is made up of material forces which are dialectical, and that communism is the dialectical resolution of the class antagonisms of history. But serious Marxists believed that anyone who really wanted to enter into the inwards of the development of history had to read their Hegel. Albeit, by never forgetting that philosophy, as Marx had explained, consisted of two teams, idealists (those who thought the world came from their own heads) and materialists (the smart ones who knew there was a world outside of the head).

Thankfully, cholera had taken Hegel out before he had to read this nonsense, which was first aired by Marx’s pal, Ludwig Feuerbach, who failing to understand that when Hegel wrote a work on logic, he was writing (to be sure, it was a radical exposition and argument) on the process involved in how we think. Feuerbach, to great applause from Marx, criticized Hegel for not understanding that if he closed his eyes and wandered unawares into a tree, the bump would teach him the tree existed independently of his thought or knowledge about it. Pathetic, isn’t it?

Even Marx, as he got older, realized that really Hegel (he and Engels would refer to him affectionately in their correspondences as “the old boy”) was a much smarter dude than Feuerbach, who by then had taken his materialism to such dizzying heights as coming up with the formulation “one is what one eats” – in the German it looks cleverer – and thus becoming a forefather of today’s dietary obsessives.

Still, Marx thought that Hegel had grasped that history develops through antagonistic forces which give birth to an immanent resolution, which will ultimately enable man to reconcile himself with his essence as a cooperative labouring being. This was, to put it mildly, a cross between a trivial dilution and very silly application of Hegel’s rather profound, if ultimately unsustainable, account of how our thinking and knowledge (and hence the sciences) develop. So just as Marx and Engels had already told him, Vlad could now claim that Hegel, though a bourgeois, had been a real asset for the communists.

Lenin’s other great work of philosophical criticism was Materialism and Empirio-Criticism. It was, mainly, though not exclusively, a polemic against Ernst Mach and Richard Avenarius (two philosophers very little read today). One might well ask what on earth would a critique of two post-Kantians, trying to identify the role of cognitive operations within modern science. has to do with overthrowing the Tsar and sparking off a global revolution against capitalism? Good question. The answer is – to repeat – that Marxism was always a philosophy, and that Marxist philosophy considered any other explanation about how to think, and even what should be thought about, as an existential threat.

One of the many dangers of making a metaphysic dictate the direction of social, economic, political and cultural development is that it is a recipe for paranoia – having exaggerated what it can achieve, it then exaggerates the damage which other ideas, which do not fit into that metaphysics, may do.

This was all interestingly bought out in the book Encounters with Lenin by the Bolshevik apostate, Nicolai Valentinov (who also wrote under the name Nikolai Valentinov-Volski). He had the misfortune of telling Lenin in a conversation that he found Mach and Avenarius interesting – at which point Lenin went ballistic, frothing at the mouth and screaming about two authors, which Volski points out, he obviously had not even read. (It was only later that Lenin would sit down with their books and belatedly prove the point that even when he read their books, he failed to understand their point).

So, really being a Marxist or a Leninist boils down to a very simple and stupid thing – believing that Marx and Lenin are always right about the essential way the world is and how to fix it. The fascist decalogue simply stated “Mussolini is always right,” which made it explicit that anyone donning the black shirt should also take out his brain. Mussolini though, preferred his brainless followers to believe in the myth of the nation instead of the scientific truth of historical materialism – so at least Mussolini knew the difference between myth and science (even if he knew as little about the science of society as the Marxists did).

By insisting that their brand of socialism was scientific, Marxists were really saying that Marx had discovered a method for understanding human nature, history, society and political economy which was unassailable. So, Marx was always right. The same line of reasoning then led to the faith that Lenin was always right/Stalin was always right/Mao was always right, etc. Little wonder that the Bolsheviks so effortlessly followed the fascists in making a complete unity of their leader, their party and their people (at least the ones that did not need to be liquidated or re-educated in slave labour camps).

Of course, as the schisms got too big to hide – which is the inevitable consequence of a thinking that is both uncompromising and murderous – Marxists had to have a Reformation and work back to the beginning. Which was why the post-Stalinist, New Left, wave of Marxists also returned back to the “salon” and classroom, where Russian communism originated, i.e., among the class of intellectuals and university students – only this time, they did have a developed world to take over, and the task of institutional capture had been set out by Antonio Gramsci. But that is a whole other story.

This long excursion into Marxism-Leninism as a philosophy is really to highlight the question, how could any serious philosopher not see that this is a path to mental captivity? That a number of people, who were philosophically gifted, nevertheless capitulated, is akin to Milosz’ account of seriously gifted writers and poets becoming ideological hacks.

Kolakowski may have started going down the road to ideological hackdom. In spite of the broad sweep of the claim, one cannot help but detect a certain autobiographical note in the title as well as the opening sentence of his book from 1988, Metaphysical Horror” “A modern philosopher who has never experienced the feeling of being a charlatan is such a shallow mind that his work is probably not worth reading.”

In Metaphysical Horror Kolakowski presents the horror through the optic of a Spinozian spin of Cartesian skepticism: “If nothing truly exists except for the Absolute, the Absolute is nothing; if nothing truly exists but myself, I am nothing.” For my part, I cannot help but see this as a metaphysical extrapolation of a soul that in saving itself from the Absolute of Marxist Leninism, but asserting its own foundational certitude, is left wondering – if all of its world and its life’s meaning amounted to nothing.

Perhaps I am reading too much into this which is pitched in a manner commensurate with the timelessness of the metaphysical disposition. But as I have said, both communism and modernity are the creations of the metaphysical imagination. And having freed himself from the captivity of Marxism, Kolakowski dives into the metaphysical imagination, with its Absolute, with the kind of resolve that only a true disciple of philosophy as the search for the Absolute and the absoluteness of life’s meaning, could muster: “Once we know,” he offers in that same work, “that errors and illusions occur, questions about a reality which can never be an illusion, or truths about which no mistakes are possible, are unavoidable.”

But whereas Marx and all his progeny end up being what Eric Voegelin, the Austrian philosophical contemporary of Kolakowski and refugee from Nazism, identified as “gnosticism,” then the search for the Absolute may become, as it did for Kolakowski, a humbling affair in which one realizes that there is, again from Metaphysical Horror, “No access to an epistemological absolute, and …no privileged access to the absolute Being which might result in reliable theoretical knowledge.”

How to face up to this without absolutizing one’s own self, with all its aspiration to know, and accepting the ceaseless limits of its knowledge, is to avoid falling into the trap of nihilism. Sometimes it takes a man almost a life-time to lay out the aspect of his soul that leads him to turn off the path that seems secure and easy, but is ultimately a dead end. Kolakowski’s metaphysical writings strike me as the expression of an aspect of his soul – his character – that had to be released through exploring the most pressing conundrums that have been woven into our civilization, through the symbols of religion and the questions of philosophy.

In any case the philosopher in Kolakowski realized as a young man, with everything before him, that the stodgy metaphysical mush that passed for philosophy in communist Poland was connected to the grim reality of daily life that passed for socialism. Not being able to simply go along with the idiocy and lies any longer – a visit to Moscow in 1950 had already shown him what idiots were running the show – in 1956, he fired off a number of missives that contrasted socialist myths and reality. One, “The Death of Gods” (available in the collection of essays, Is God Happy?) seems to be the work of a writer torn between the idealism of his old self and the determination of the new self to be uncompromising about the truth:

“When at the ripe age of eighteen, we become communists, equipped with an unshakeable confidence in our own wisdom and a handful of experiences, undigested and less significant than we like to imagine, acquired in the Great Hell of war, we devote very little thought to the fact that we need communism in order to harmonize relations of production with the forces of production. It rarely occurs to us that the extremely advanced technological standards here and now, in Poland in 1945, require the immediate socialisation of the means of production if crises of overproduction are not to loom over us like storm clouds. In short, we are not good Marxists. For us, socialism, however we go about arguing for it in theoretical debates, is everything but the result of the operation of the law of value. Defended with clumsy arguments cobbled together from a cursory reading of Marx, Kautsky or Lenin, it is really just a

myth of a Better World, a vague nostalgia for human life, a rejection of the crimes and humiliations of which we have witnessed too many, a kingdom of equality and freedom, a message of great renewal, a reason for existence. We are brothers of the Paris communards, the workers during the Russian Revolution, the soldiers in the Spanish Civil War.

We thus have before us a goal that justifies everything….

We believed that socialist rule would naturally lead to the swift and total disappearance of national hostility, nationalist prejudice and tribal conflict. Instead we found that political activity which goes by the name of socialist can encourage and exploit the most absurd forms of chauvinism and blind nationalist megalomania. In culture these manifest themselves in the form of naive deceptions and infantile sophistry, but in politics, concealed behind a thin façade of traditional internationalist slogans, they assume the much more dangerous and sinister form of colonialism.”

Another from that same year was “What is Socialism?” which is basically a list depicting the totalitarian reality of life in a communist country, that is preceded by the sentence, “Here, then, is a list of what socialism is not,” and first on the list was “a society in which someone who has committed no crime sits at home waiting for the police.”

It is true that Kolakowski was not alone in speaking out against what socialism had become and he was swept up in a hopeful wave of defiance and bravery. And it is this importance of this bravery that cannot be underestimated when one considers how totalitarian regimes come undone: ideas are nothing in themselves, they are made by people and they make people. That is to say, bad and stupid ideas only take off and become instruments of annihilation, cruelty and stupidity because they appeal to and help make people who are ready to kill, be cruel, imprison others who aren’t as stupid as they are, that is people who will stop at nothing to get their way and who have no doubt about the rectitude of their view of the world and the solutions to its ailments.

All the pesky Poles mentioned in this essay would have had an easier and cushier life in Poland and the USA had they just gone along with the cruel and stupid ideological conformists and enforcers, who had and have all lost their minds, hearts and souls. Milosz could not have come up with a more prescient title than the Captive Mind if he had to depict what is happening today. But the shocking thing is how easily today our Western intellectuals and academics have entered into mental captivity.

In part, this is because they had already swallowed the poison of liberal freedom that both Legutko and Janowski address. And whereas they had done so in the tenured and most comfortable of circumstances, the writers, poets, philosophers whom Milosz depicts in the Captive Mind had lived through a time of extraordinary suffering. The poet Beta (a pseudonym for Tadeusz Borowski), for example, had been in Auschwitz, and witnessed and chose to survive by doing all that was required of him by his Nazi masters.

Perhaps souls like Borowski were simply harder to ensnare, and perhaps we in the West have been breeding monsters of ignorance who have now become ignorant monsters, and they are so sensitive they suffer like someone upon the rack if they but think of anyone who does not believe that the sum total of their knowledge (which could fit on a tiny packet of cards) for understanding and judging the past, present and future of the human race suffices for total emancipation.

For, let’s be real –ideologues typically enter into a state of apoplexy when someone challenges their diagnosis or remedies of a state of affairs which they designate as social injustice because they do not want anyone challenging their authority – the “injustice” is just a “trigger” (hence the need for trigger warnings) sending them into states of rage. This is not to deny the existence of social injustices; but today’s woke would not know how to identify, let alone fix, an injustice (for that would require thoughtfulness, and nuance) if it were ripping out their entrails.

When one reads Milosz, one is saddened by humans with characters and talents who were lost to communism, when one reads today’s woke journalists or academics or listens to the hysterical screaming of the kids demanding the world be what will make them feel safe (no police, for example, or no “whiteness”), the sadness is not in characters that have been lost, but in characters that have been malformed from the moment they could talk, and thus who have no notion of what it is to think.

The first wave of pesky Poles had often initially swallowed the poison of socialism. Milosz and Kolakowski had both had promising careers with the communist regime – Milosz was a cultural attaché in the United States and Paris, though falling foul of the party, he was able to find political asylum in France and then move to the United States. His Captive Mind was an early exposé of what communism did to the soul and it which quickly became a modern classic.

Kolakowski’s intellectual journey away from socialism was a far slower one – from believer to “revisionist,” during the so-called “Gomulka thaw,” when the Polish communist party itself was seeking for new ways to socialism, to disbeliever. As an exile, first in Montreal (where he taught at McGill) in 1968, Berkeley (University of California) in 1969, and then Oxford in 1970, he was free to philosophically engage in the two topics that seem to me (though I have not read his entire corpus) to be his major preoccupation: the metaphysical needs of the human spirit, and the disaster of Marxism as an “answer” to that need.

In the West he saw first-hand how the kinds of ideas that he had believed in in his youth were being recycled by the New Left. The irony was that Kolakowski himself had been something of an inspiration for the New Left. To them , and any others who were interested, Kolakowski would have to spell out what everyone (except a historically insignificant number of Trotsky supporters and the New Left) knew – Stalinism had Marxist roots a theme that would be developed at length in his magisterial three volume study Main Currents of Marxism (written between 1968 and 1976, and originally appearing in English in 1978).

Prior to that, in 1973, the English historian and anti-nuclear weapons activist, E. P. Thompson, had written an extremely long piece, “An Open Letter to Leszek Kolakowski,” for The Socialist Register. Thompson was a pioneer of the British New Left, and a founder of the Marxist journal, The New Reasoner which would morph into the New Left Review. He had achieved some fame with his book of 1963, The Making of the English Working Class. I bought the book, as an earnest young man, some forty years ago, and while, it contains serious history which indicates what Thompson could have been without the romanticism and Marxism, it is, nevertheless, about as riveting as a trade union meeting. (Thompson liked Blake – and I love Blake – but sadly Marx ruined his mind and nothing of Blake’s poetic brilliance seeped into his writing.) I quote from its opening paragraphs to give you an idea of the kind of Marxist casuistry, doggerel and dogma that cluttered his mind:

“This book has a clumsy title, but it is one which meets its purpose. Making, because it is a study in an active process, which owes as much to agency as to conditioning. The working class did not rise like the sun at an appointed time. It was present at its own making. Class, rather than classes, for reasons which it is one purpose of this book to examine. There is, of course, a difference. “Working classes” is a descriptive term, which evades as much as it defines. It ties loosely together a bundle of discrete phenomena. There were tailors here and weavers there, and together they make up the working classes. By class I understand an historical phenomenon, unifying a number of disparate and seemingly unconnected events, both in the raw material of experience and in consciousness. I emphasise that it is an historical phenomenon. I do not see class as a “structure”, nor even as a “category”, but as something which in fact happens (and can be shown to have happened) in human relationships.”

Hello! Are you still there?

In 1978, the bit about not seeing class as a structure would become the source of a theoretical dispute between him and the French structuralist Marxist Louis Althusser – he who strangled his, equally mentally disturbed, wife. Althusser even wrote a book about it, in which he revealed that his Mum was at the root all those problems in his life that capitalism was not to blame for – i.e. whatever part of his mind and soul Marx had not destroyed was finished off by Freud.

In any case, before Althusser was a garden variety philosophical wife-strangler (and funnily enough this domestic act did not irrevocably damage his brand with Marxist feminists), and an ex-asylum inmate roaming the Parisian streets in his pyjamas exclaiming, “I am the great Althusser,” he was the epitome of Parisian Marxist cool – close to the trés cool Derrida and Foucault – and hence a leading light for those wanting to lead the rest of us poor saps into a world free from the murderousness of private property.

The Althusser-Thompson dispute was a dreadfully tedious piece of rationalism, in which Thompson ostensibly defended Marxism as empiricism. To be fair, in the windbaggery department Althusser was a veritable Zeppelin in comparison to Thompson’s mere hot air balloon, and, to change metaphors, in the great Marxist “bake-off,” it was a rather drab English mince-pie, albeit garnished with some slices of wit, versus a delicate Parisian soufflé – light, with an airy texture that requires years and years of dedication to understanding how to generate enough hot air by merely blowing long and hard enough into one’s selected chosen ingredients – a little Marx, tossed with a dollop of Lenin, and throw in a pinch of Spinoza: voilà who would need to know anything more.

Long before this and even before the Open Letter, Kolakowski, who I suspect was more given to blintz than soufflé, did a review of Althusser in the 1971 issue of The Socialist Register. It concluded that Althusser amounted to “empty verbosity which … can be reduced either to common sense trivialities in new verbal disguise.” I mention this just to give those readers who were not there a picture of what was passing for serious thought among Marxist intellectuals when Kolakowski was teaching at Oxford, and around the time Thompson’s “Open Letter” was published.

The major purpose of the hundred-page Letter was to express Thompson’s personal “sense of injury and betrayal” that Kolakowski had left the team. In the typical self-congratulatory moral tones that have become the hallmark of the post-Stalinist left, Thompson instructed Kolakowski that he did not affirm his allegiance to the Communist Party (though he never realized that he did not need to do so to be their stooge in the nuclear disarmament campaign) – he was committed to the “Communist movement in its humanist potential.”

Even such a rhetorical gem – in an attempt to ingratiate himself with Kolakowski – as “Communism was a complex noun which included Leszek Kolakowski” could not conceal the fact that Thompson, for all his reading and historical digging, was a know-all and hence, in spite of all his learnedness, was another Western useful idiot. Thus, the irony in the title of Kolakowski’s “rejoinder” to Thompson: My Correct Views on Everything. For what is obvious to anyone who reads My Correct Views is that Thompson, whose Open Letter the Marxist critic Raymond Williams himself (most tellingly) calls “one of the best Leftist pieces of Leftist writing in the last decade” (one can only imagine how bad the others were) is an “embarras de richesses” of clichés and abstract vacuities, expressing a depth of moral self-delusion that enables Thompson to glide over the true suffering of people living in a system that politically ensures a society without private property. Thus, he is able to write with a great sweep of his quill that “to a historian, fifty years is too short a time to judge a new social system.” Kolakowski, as one might expect, does not let this pass. But the real strength of Kolakowski’s rejoinder is in his own admission of modesty:

“I share without restrictions your (and Marx’s, and Shakespeare’s, and many others’) analysis to the effect that it is very deplorable that people’s minds are occupied with the endless pursuit of money, that needs have a magic power of infinite growth and that the profit motive, not use value, rules production. Your superiority consists in that you know exactly how to get rid of all this and I do not.”

Near the conclusion of the rejoinder, Kolakowski takes up this theme of the complexity of the problem when he writes:

“This does not mean that socialism is a dead option. I do not think it is. But I do think that this option was destroyed not only by the experience of socialist states, but because of the self-confidence of its adherents, by their inability to face both the limits of our efforts to change society and the incompatibility of the demands and values which made up their creed. In short, that the meaning of this option has to be revised entirely, from the very roots.”

As excellent as Kolakowski’s three volume analysis of Marxism was, not least for addressing the spiritual longing that reside within its materialist heart – thus for Kolakowski, understanding Marxism requires thinking about Plotinus, Meister Eckart, Jacob Böhme, and Nicholas Cusa as well as the usual philosophical suspects of German idealism and the young Hegelians – it did not halt the Gramscian inflexion that had taken hold of British Marxism. That was mainly thanks to the New Left Review which had been translating Gramsci and hence introducing him to British intellectuals. Though by then Thompson had fallen foul of the far slicker and more theoretically savvy Perry Anderson and his faction within the New Left Review.

Also, sadly for the battle that Kolakowski was fighting, Althusser was but one of the Parisians who were to 1968 what the young Hegelians had been to 1844-48. A slew of “radical chicsters” were sexing up a philosophical, literary and sociological potpourri of Marx peppered with dollops of de Sade, and Nietzsche and sprigs of Heidegger – they were attacking totalizing narratives, and embracing the emancipatory potential of the marginals (Foucault extended his emancipatory largess from prisoners to paedophiles), who were deployed in the grand game of leading us to emancipation.

So. while Kolakowski was providing a lengthy and perceptive analysis of how the gulag gruel of communism came to be, the game plan had changed and the New Left were in the process of dropping the workers for any other group that could be construed as a minority. Old style British Marxists naturally enough were not so hot about all this – after all they (at least the serious ones) had wracked their brains over the three volumes of Capital, the Grundrisse, and the six volumes of Theories of Surplus Value – and they fought a losing battle against the French post-structuralists over who would be the hegemons of the university and the new society at large.

The theoretical disputes mattered as little in the late 1960s and 1970s as the disputes within and between Bolsheviks, Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries had mattered prior to the breakup of the Russian empire – what mattered was that a generation of educated young people with all their radical certitudes (in all their diversity) about power, oppression, capitalism, Eurocentrism and the panoply of social injustices and victims they would rescue were catapulted into positions of pedagogical authority by a society wishing to reproduce itself through educating its professionals. The Soviets knew exactly what was going on – for it was a replay of the process that had, albeit with the catalyst of the Great War, led to the demise of the Tzar, and were able to fuel the youthful arrogance of the class they could count onto hand them a (too belated) victory.

Kolakowski, though, could do nothing to stop this, any more than he could have stopped a flood with an umbrella – he was not only of the wrong generation, but on the wrong side of historical experience. He was the past and a man of considerable experience about the nature of communism. But it was the generation who saw themselves as being of the future who were indeed making the future– and their sense of experience was generally (with the exception of the casualties of the Vietnam war in the US and Australasia) one of sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll and educational and job opportunities.

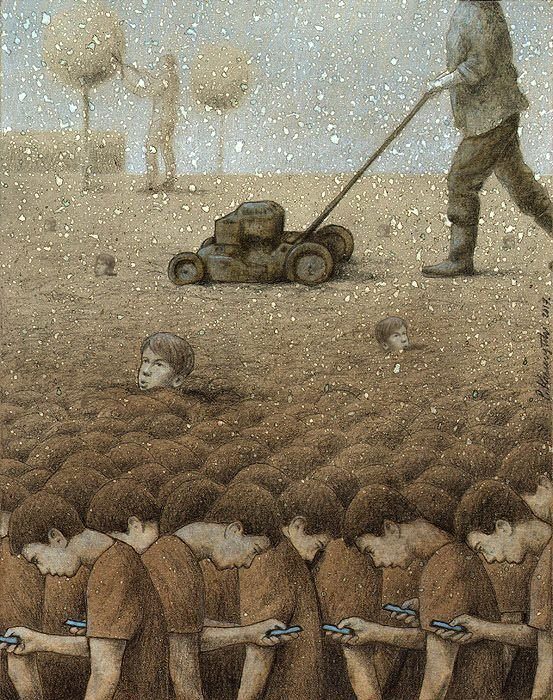

Even when the economic impediments of the 1970s kicked in, the model of mass education for social reproduction had been set, and then it was just a matter of time before the curriculum had been so politicized that the universities would become what they are now – managerially administered industrial sites for the making of a compliant globalist workforce shorn of the old bulwarks of sociality from the family, to the church, to the nation, and refabricated on the basis of race, gender and sexual preference.

Apart from Kolakowski, Milosz and Wat, trying to get Westerners to see the how, what and why of totalitarianism, the Polish historian Andrezj Walicki, especially his writings A History of Russian Thought from the Enlightenment to Marxism (1979), and Marxism and the Leap to the Kingdom of Freedom: The Rise and Fall of Communism (1995) provided an in-depth critique not only of Marxism, and its development but of the various ideological dreamings that helped turn Russia and its Soviet empire and satellites into a world that reflected back what designs of perfection actually deliver.

More to the point, the class of intellectuals in the West who might have benefitted from historical knowledge about the intellectual product of communism were not that interested in such writers or their diagnosis. Sadly, then, there was no contest, for the young professors and students, between Derrida/ Foucault versus Walicki /or Kolakowski –the former were superstars (and they were clever in the same way that a kid that can count to a hundred in Latin, balancing a stick on the end of his nose while juggling bunny rabbits for a while is clever), while the latter really knew they were talking about, especially when it came to how ideas of absolute liberty, and equality and the end of oppression would turn out.

But the professors and their students were interested in identifying all the things they were sure they could fix, not with learning about how little they actually knew. Ambition, arrogance, rhetoric, formulae, facileness, slogans – indeed the exact same ingredients of self-making that had been the brew and bake of the old left, was the brew and bake of the new left. Men like Kolakowski, Walicki, Milosz, Wat were voices for such old virtues as humility in the face of historical complexity and the need to accept the limits of human achievement and the inevitability of error, weakness and ignorance.

Around much the same time, as Kolakowski was starting his life in the West, another Polish writer and refugee from communism, Leopold Tyrmand, who had written a modern anti-totalitarian classic setting down the routines of communist daily life, The Rosa Luxemburg Contraceptives Cooperative: A Primer on Communist Civilization (1972), also (Notebooks of a Dilettante [1970]) reported that at a dinner party in America “a distinguished Negro writer” asked him what percentage of the population would vote anti-Communist if there were free elections in an Eastern European country.

When Tyrmand responded that, if the elections were really free and all positions could be presented, and if there were no fear of persecution, then it would be about 85 percent, the writer responded, “I don’t believe it”- a little later exclaiming more heatedly, when Tyrmand tried to explain how things worked in Poland: “It’s impossible! It’s against any logic!” And that really is the point: people who have no knowledge about something are convinced they do, provided they think it is the kind of thing they think is of political importance.

This is what ideology and education do. This is what the captive mind is. But in Milosz’ work of that title, minds were generally captured by circumstances harrowing, fearful and brutal enough to draw out a certain weakness of the soul. But today in the West it is liberty itself that has exposed the weaknesses of soul that now presides over the political and social institutions of the West. And whilst there are some fine diagnosticians of the current and very likely fatal pathology of the West, two Polish authors, Ryzsard Legutko, and Zbigniew Janowski have written works that take us into the heart of the matter.

3. Exposing The Dialectic of Totalitarian Freedom

When Hannah Arendt wrote what would become a class of political science, The Origins of Totalitarianism, liberal democracy was considered to be a form of government in which the state had clear identifiable limits. This distinction between a state that had limitations and freedom was not just a theoretical one – people wanting to escape from the control of the state and a particular ideology had, if they could manage to get there; somewhere to escape to.

Thus, it was that a number people, including the Polish intellectuals mentioned above, who could not stand the lack of freedom, the brutality, the ideological imbecility, the incessant brainwashing and ludicrous lies of communism fled to the West. It was much the same for people escaping from Nazi Germany – though the poor bastard communists who escaped from Nazi Germany to the Soviet Union were frequently caught up in the anti-foreign campaign of the great purge and all too often found themselves in gulags or simply before a firing squad. One of the distinctive insights of Arendt’s book was her argument that the French Declaration of the Rights of Man did not serve as a means to prevent the rise of forces that would lead to totalitarianism, but rather exposed groups of people who lay outside the protection of the nation and thereby found themselves as victims of persecution within the nation.

This insight of Arendt’s is a good example of how an idea, or principle may develop into its opposite. And although Marxists generally loved to talk of dialectics, anyone who really thought dialectically could see that Marxism was a power for the extinction of all classes and ideological enemies that were perceived as obstacles to those who lived off the narrative that they enforced on others. That is, it was simply a will to power of a bunch of people who thought they knew how to rule their world to get what they wanted – which they think everybody wants – no private property, and no religion etc. for example.

One might say that the reason for this is that the dialectic that transpired was between the willfulness of a group wanting their world to be a certain way and the stubbornness of the world (i.e. lots of other people) to resist that way. The problem has to do with ideology itself. For reality (including real human beings) refuses to simply yield to abstractions that only exist due to not taking into account those parts of reality that the subject or knower simply has no inkling of or care for. Communism was just one example of that failure. Fascism was another. And liberalism is yet another.

Liberalism, though, has been somewhat slower in revealing its totalitarian essence (though some – to take three very different kinds of people – like de Maistre, Tocqueville, and Newman clearly saw its weaknesses), and, unlike Fascism and Communism, its shortcoming did not require death or labour camps. But the time of revelation is now upon us. Would that it were not the case – would that liberty could prevail over all else. But it cannot, for liberty is a concept of some complexity, and even then, it is, at best, only an aspect of a life, and when we seek to make any aspect of life the essence or condition of life – we mess up.

Ryszard Legutko’s The Demon in Democracy, and The Cunning of Freedom: Saving the Self in an Age of False Idols, and Zbiegniew Janowski’s Homo Americanus: The Rise of Totalitarian Democracy in America examine the mess.

Part of the mess simply comes from ideology itself – the desire to simplify the complexities of the real to conform to a narrative, pattern of policy and legislation and the institutions of social reproduction which will solve our most pressing problems. The problems of political obligation, of who has the right to decree what must be done to whom, and who must be followed in order keep the peace between members of the social body, are perennial.

Problems between “groups” and within them have led to a relatively limited number of solutions – this is because the problems are very similar as are the means for solving them: someone or few must make decisions that the community must comply with, there must be some way of passing on succession etc. In this respect all “political” organization is inevitably hierarchical and elite-based–obviously how the elite is selected and what is expected of them varies significantly.

Historically, that elite had evolved out of the power they displayed – usually this display was exhibited on the battlefield, though power to engage the gods was always another aspect involved in the power formation and distribution of the society. Monarchy and aristocracy are generally and essentially derived from military victory, and the power of the monarch is also derived from capacity to command the requisite alliances that sustain the peace between potential contesting powers.

Although Plato and Aristotle had envisaged a kind of political order based upon the best ideas and insights that could organize a society – until modern times this was merely a philosophical pipedream. But modernity itself, in its technological and administrative and economic and political innovations is inseparable from the emergence of a new elite, whose bread-and-butter was (as the philosopher John Locke called it) “the way of ideas.”

As the number of people appealing to and living off ideas spread the entire way of understanding political authority changed. Modern social contract theory was one symptom of the change – for each of the contract theorists envisaged a rational reconstruction of the origins of social and political development. More important than the fact that a handful of philosophers were writing about the rational foundations of society and political authority was the fact that a public who were interested in discussing ideas generally, and, more specifically, how a society should be organized was developing.

The tensions between the Americans and the British crown provided the opportunity for a relatively small group of educated men to draft a new political order in a world relatively unencumbered by past vestiges of authority, that would in turn inspire a class in a part of the old world able to find its moment in the ruins of a financial and social breakdown that it had helped on its way. For good and bad, France, albeit initially for only a relatively brief time, had provided the old world with a new way of doing and speaking about political authority.

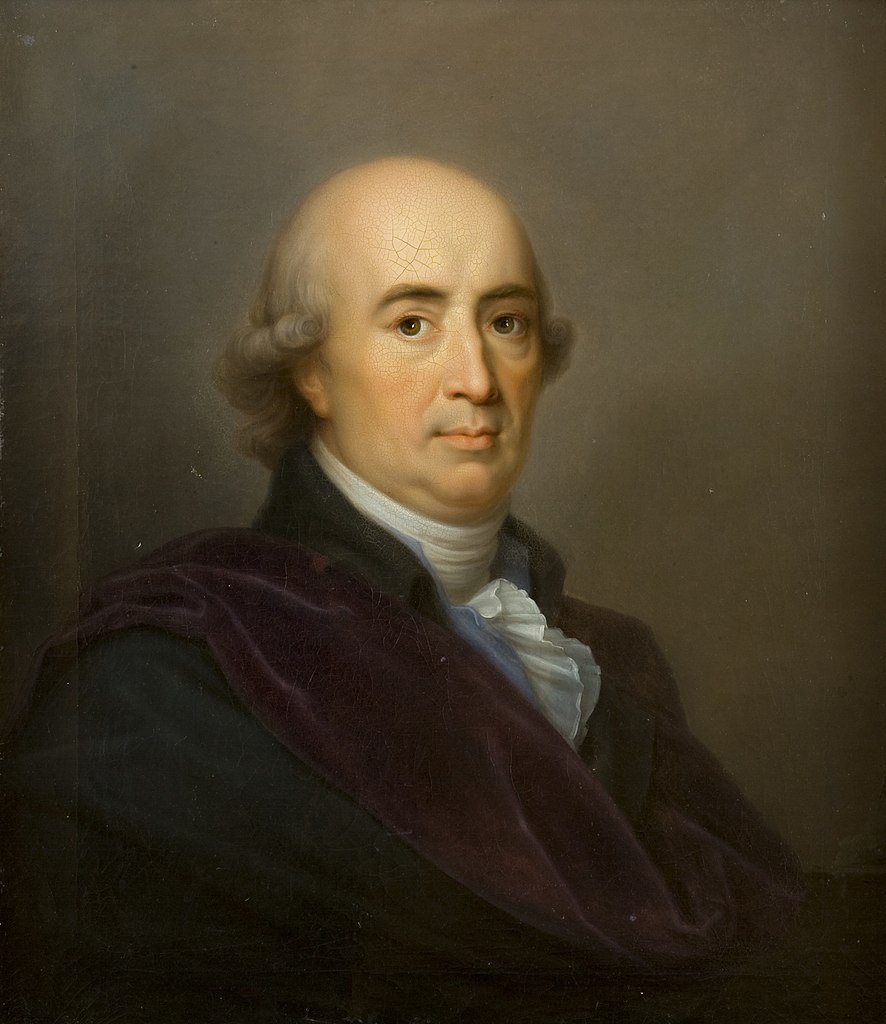

For all the chaos of the French revolution, and the geopolitical consequences that it triggered, politics and ideology became increasingly entangled. The history of the very word ideology comes from one of the revolution’s great survivors, a philosopher and political economist, Destutt de Tracy. That is, politics became not only something that concerned people interested in ideas, it itself became equivalent to a practice which primarily required getting the right ideas to fit a world which would conform to the ideas that its educated elite had about it. There were ideological differences between different thinkers and members of the public, but thinking of politics as a political matter was becoming increasingly commonplace, so that political choices were invariably ideological choices.

This is the background against which Legutko’s book needs to be read. For the young students and staff who tried to prevent him talking at Middlebury are so sadly ignorant of where they fit within the larger forces that have bred them that they simply dismiss him as a conservative -i.e., they reduce him to an ideology – whilst seeing themselves as the guardians of freedom and justice and human decency.

The operative word though is that they are guardians, and they guard what they think, which is all too little to do justice to the scale of the problems we can divide between the perennial and the peculiarly modern. Were they aware of that, the first idea they would have to dispense with, apart from their own faith in their knowledge, is that the kinds of problems that all people including modern people inherit and generate do not all have a neat – if indeed any – solution.

The idea that there is a political pattern with a happy ending, a pattern that politically eliminates the tragic features of life is completely crazy – and even non-religious people, who are thoughtful, should be able to appreciate that one benefit of believing in the after-life is that we do not become burdened by things we cannot achieve – nor completely delusional about our capacities to do what only a God would have the power to do such as see how all things fit together. (Which is why of all the metaphysicians, I have always had a soft spot for Leibniz).

Not surprisingly, people who think they know how things all fit, and hence how to politically solve our problems tend to be very similar – irrespective of their particular ideological convictions. One is reminded of the French fascist author Drieu de la Rochelle agonizing about which team to choose as there was so little real difference between them.

In terms of his reputation, he chose the wrong one, his friend Malraux the acceptable one – but both chose murderous regimes. In terms of the character of the people who are drawn to become ideologically and politically involved Legutko observes of the transition in Poland from communism to liberal democracy how swiftly “former members of the Communist party adapted themselves perfectly to liberal democracy, its mechanisms, and the entire ideological interpretation that accompanied these mechanisms. Soon they even joined the ranks of the guardians of the new orthodoxy.” This is because they were first and foremost guardians, and in this respect no different from the Western politician who immediately adapts the ideological ideas to political realities that he must confront.

While guardians can quickly switch ideologies, today they are programmed to think ideologically. And, for me, the power of Legutko’s analysis lies in his recognition of the depth of the problem of ideology itself. For while during the Second World War, or the Cold War liberal democracy looked – and indeed was – so much better than the alternatives, the fact remains that it rests upon abstractions such as freedom and equality which, if taken as things in themselves, are not only socially damaging, but which also contribute to the elimination not only of actual freedoms, but of aspects of sociality which are intrinsic to humans convivially cooperating and bonding across time. Thus, the kind of love a parent has for its child, or that exists between husband and wife, and even between friends simply cannot be fathomed if we think exclusively in terms of qualities like freedom and/ or equality. Living relationships are intrinsically and necessarily sacrificial.

The broken families that litter the liberal democratic world, are testimony to the triumph of liberty in the formation of relationships, but they are also symptomatic of the problems that befall a society in which the sacrificial is ousted by a mélange of pleasure, comfort and abstraction. Where the problem of broken families makes itself most conspicuous is where the material resources which, though no surrogate for love, enable other forms of communal engagement are lacking – that is among the poorest sections of the society.

Being from privileged backgrounds or at least being able to access resources which gave them opportunities that those dwelling in ghettoes do not have, the Middlebury brats threatening to silence Legutko were particularly outraged by his diagnosis of the damage done by the sexual revolution, warnings against marriage break-down and abortion. For the ideologue such warnings must be ideologically dismissed because they are conservative.

But the truth, of Legutko’s warning, is palpable amongst the American blacks, that is amongst the class which these imbecilic brats claim to somehow speak for and represent, along with single mothers from the white underclass whose domestic life is so frequently one of violence at the hands of men who move in with them when it is convenient to do so, and out as soon as a better opportunity arises. (More’s the pity that most students who study the social sciences and humanities would have no idea of the writings of Theodor Dalrymple aka Anthony Daniels).

It is sheer thoughtlessness that could lead one to think that freedom is a panacea for solving the kinds of problems that can only be dealt with by foregoing freedom, by accepting sacrifice – and the sacrifice that is paid for by single mothers, abandoned by the children’s fathers confirms the dialectical entanglement in which freedom frequently generates its opposite.

Thus, it is that Legutko, and this is also true of Janowski, which has also led him to track down J.S. Mill’s complicity in this madness, warns his readers that the breakup of the world into the seekers and enemies of freedom is ridiculous.

As indicated by the subtitle of the Freedom book Legutko recognizes that liberal democracy’s promise of salvation is idolatrous. It is not that liberty does not have its place amongst those aspects of the human spirit that give meaning and value in a life or to a collective, but an aspect is not a god. The endless search for the realization of liberty ultimately becomes a tearing down of the social and personal dwellings of the spirit that give it a purposeful sense of place.

The cloud of the abstract replaces the solidity of real relationships, with their compromises and imperfections, and the regular routine duties which are the condition of their nourishment. Liberty today has become indistinguishable from the short-lived thrill of a sexual encounter – “the sexual revolution,” says Legutko, “is arguably the most extreme manifestation of the episodic nature of man.” That something as ephemeral as the sex act can become the basis of an identity to be used as a foundation for the structuring of society – thus requiring an endless array of writings and university courses about its importance – is indicative of a people infantilizing, and pleasuring its way into hell.

Progressives think that their virtue will not only spare them this fate, but will contribute to them creating very heaven. But these are people whose “virtue” has no benign existential bearing, nor even basic moral bearing in so far as they are members of a class whose power is predicated upon the narrative they learn, conform to, preach, and protect at all cost.

Hence, diversity, identity, equity and such like are the institutional paper currency of the will to power of a poorly educated, highly ambitious, envious, and endlessly egocentric elite who base everything upon identity and representation because they are so devoid of any real self. Their freedom is their emptiness – and their creation, as Legutko, names one chapter in his Freedom book, is “the wretched world of absolute freedom.” Such freedom is what Isaiah Berlin had defended as “negative freedom” in “Two Concepts of Liberty.” And when communism was offering something that was positively revolting, negative freedom looked like it had much going for it. Thus, Berlin’s essay, which Legutko had once considered to be inspirational, now appears to Legutko, merely a “collection of platitudes and falsehoods.”

For Legutko, far from being an ideal that was self-explanatory and invaluable, freedom has proven to be a philosophical problem – and in the West it has “got into the hands and minds of dogmatists who turned it first into a rigid, ultimately fruitless formula, and then into an ideological tool to promote a liberal model of society that I found increasingly dubious.”

The problem that has been revealed to anyone with eyes to see is the problem that “once one particular group’s freedom is confused with the legal framework of freedom, then the language of freedom is likely to become mendacious” – and that is exactly what has happened over the last two generations or so in the Western world. In an essay in the first volume of Janoswki’s collected edition of writings by J.S. Mill, Legutko had pointed out how the harm principle simply becomes the means for a group wanting to entrench practices previously considered socially undesirable making the mores, that had been intrinsic to social development, a pariah position – as has happened now with the dismantling of the traditional family and its roles.

The great myth of liberalism is that everyone’s freedom can be maximized – so as Legutko puts it – it is a society that would resemble “a department store in which everything is offered, everyone can find what they want, no one feels undeserved, one can change one’s preferences, and even the most selective desires can be satisfied.”

Peoples that were once enemies now get along swimmingly well because all get what they want – hey you can get the burka, and I can get the bikini briefs that best display my twerk – provided, of course, the submit to the rules, which require a severe surgical reconstruction of what one actually wants. This is the squared circle of a society, one in which two fundamentally incompatible loyalties – loyalty to one’s own community, and loyalty to an infinitely open system – are falsely seen as both desirable and achievable.

I used the word myth above, but the myth is really little more than a lie. And the chaos of the Western world is in large part the result of the exposure of the lie as lie, which has brought out the savage and tyrannical reaction of the “de facto rulers, educators, ideologues, guardians, and censors for all members of the society.” That chaos has been facilitated, in no small part, by the elevation of such abstractions as “human rights” which simply enable the proliferation of claimants for conditions which someone has to supply, and recognition for qualities and behaviour which someone has to give, which only fuel the expansion of a class who control not only actions, but words, and thoughts right down to which pronouns are permissible.

Against the modern doctrinal approach to freedom that has been enwrapped in a dialectic of tyranny, Legutko, drawing upon Aristotle and Plato, defends a more nuanced and classically developed notion of freedom that moves from the unlimited and unconstrained idea of freedom of a self with its vacuous sense of dignity and hedonistic drives to an understanding of the self as requiring an inner strength that results from cultivating the virtues and hence taking on the sacrifices that are the precondition of those virtues.

In Plato and Aristotle freedom as such was never a virtue, rather it is a quality of the self that is an out-growth of the development of the virtues. Readers familiar with Aristotle will recall his famous distinction between those who are slaves by nature and those who may through circumstances fall into slavery, which is suggestive of freedom being as much a disposition and not simply a legal or political one.

In this sense the classical position offers a stark reminder of how mistaken modern philosophy has been in taking abstract political goals and abstract characteristics as sufficient in themselves, whilst failing to take into account the cultivation of the self through service and obligation. Legutko reflects upon the positive freedom to be found in such lives as the philosopher, the entrepreneur, the artist and “aristocrat,” whilst drawing his reader’s attention to how each type easily becomes distorted in its modern formation because the modern self is based upon an original fundamental failure to understand not only the soul and its needs, but how the failure to cultivate its development results in the kind of mess we inhabit.

It is the lack of cultivation of free inner selves that Legutko identifies as what has been lost in the obsession with emancipation that has only emptiness as its goal. Near the conclusion of the Cunning of Freedom Legutko observes – “Living is a constant process of making sense of what’s finite in the light of what’s infinite, and of what’s contingent in the light of what’s absolute.”

The West’s tragedy is, in part at least, the ruin that comes from a failure not only to understand the laws of the spirit, but from the ideological spread of a way of thinking and being, in which those laws are buried under the weight of the finite’s own self obsession and delusions about its infinitude.

What we now have is a great mass of deluded selves constituting a pyramid presided over by the emptiest and most deluded, by the people who claim to know the All that needs to be known (the infinite as such), but who in fact know next to nothing about themselves or the world.

One only has to think of the fact that the academic study of literature in the most prestigious universities in the world does not teach how to better fathom human lives, souls, and characters, with their respective trials, circumstances, fatalities, triumphs and defeats, virtues and flaws, but to read texts as ciphers of power relations constituted by identity types. Professors and students endlessly repeat Althusser’s view of the social world as consisting of subject-less structural “bearers” in the grim and endless identity struggles for “emancipation.”

While the word emancipation is a void, defined by nothing more than the absence of oppression, we may glean some meaning of the word from the common French post-structuralist alignment of Sade (with his gargantuan mechanics of death for the pleasure of the killers), Nietzsche (with his fantasy of higher men and supermen who are beyond good and evil and are the creators of value), and Marx (with his view of unalienated life being bound up with our labouring cooperative essence).

As a vision statement it looks (in the immortal words of Johnny Rotten) ‘”Pretty Vacant,” but that is the point. For what we are witnessing now is a carbon copy of Russian’s nineteenth century with its alliance of intelligentsia and students: the complete preoccupation with emancipation and the dehumanization of any who impede their “emancipation.”

Thus, the meaning of life is read exclusively in terms of unequal power relations, and the dyadic norms that they see as all important – oppressor/ oppressed, privilege/ equity, inclusiveness/ exclusiveness, whiteness/ non-whiteness, diversity/ lack of diversity, rich/ poor, cisgender/sexual fluidity. In what became the Soviet Union, once the politicized Russian intelligentsia successfully broke down and then took control of all social and political institutions, they moved from having dehumanized their enemy (those on the wrong side of the normative dyad) into a phase of extermination.

It is the first phase of the totalitarian reality of the United States today that is the subject of Janowski’s Homo Americanus, a searing indictment of how every-day and valuable freedoms in the United States – especially the freedom to “openly or publicly” express “opinions which are not in conformity” with “what the majority considers acceptable at the moment” have become suffocated by a surfeit of democratic intrusions, into “virtually all aspects of man’s existence.”

Though it is not so much the opinions which the majority hold, but the opinions which the majority of the elite hold that are the problem. This is one of two instances where I think Janowski mistakes the sentiments and ideas that circulate amongst the ideas brokers in the US with the majority of the population.

The other is in the opening sentence, “Only few Americans seem to understand that we, here in the United States, are living in a totalitarian reality, or one that is quickly approaching it” strikes a note of warning. But given that now almost half the country believe that their president was not elected, were Janowski’s book more widely publicized I think it would have a huge audience. These are trivial matters in a book that I think is as relevant to today as Bloom’s Closing of the American Mind was a generation ago – though I think Janowski’s diagnosis is far sharper, and not given to the kind of (Straussian) idiosyncrasies that make Bloom’s version of history look like a library shelf.

Perhaps the sentence that best sums up Janowski’s “thesis” is: “The anti- communist opposition, just like Western political scientists, did not understand that 1989 was not a moment of liberation, but the moment when one collectivist ideology (communism) was replaced by another collectivist ideology (democracy).” I think this is a brilliant insight into the historically complex and dialectical entanglements which may help us identify the vast expansion of democracy beyond “its electoral confines” so that today “Equality is our New Faith.”

Although it is indicative of the high speed of acceleration occurring right now, as this elite program steam rolls over all resistance, that the word equality is viewed with less favour than it was even last year, when Janowski was still writing the book: for now, the New Word/Faith is Equity. Though, Homo Americanus is not so much an argument for this claim as a testimony of it. And for all the many authors Janowski engages with to depict the tragedy he is witnessing, the writing reminded me of none so much as Joseph Roth who chronicled the rising historically unstoppable evil of Nazism. St. Augustine’s Press are to be congratulated for publishing a book that is so urgently needed and yet so out of step with the pre-occupations and obsessions of mainstream academia today.

Nevertheless, the fact that it is a small independent (albeit quality) publisher that has taken on Homo Americanus rather than a major academic or commercial publisher is indicative of the times. For it would never have got through the gatekeeping staff within the major presses, who simply cannot get enough books on sexual or (non-white) racial identity, oppression, and emancipation. Mainstream publishing today is generally committed to ensuring that the USA follow its elite headlong into oblivion.