We are happy to have this opportunity to speak with Colonel Jacques Baud about Alexei Navalny, a man touted in the West as a “hero.” Colonel Baud sets the record straight.

The Postil (TP): Now that an Oscar has gone to the documentary Navalny, and given your own excellent book (The Navalny Case: Conspiracy to Serve Foreign Policy), which rigorously undermines everything that this documentary presents as the “truth,” please help us understand, and get beyond, this “mystique” of Alexei Navalny. What is it about Alexei Navalny that appeals to the West?

Jacques Baud (JB): Like other characters picked by the West (like Juan Guaido in Venezuela or Svetlana Tikhanovskaya in Belarus), he gives the image of a new, good looking, younger, more dynamic leadership. He is very present on social networks, where he has the vast majority of his audience. He therefore speaks to a young audience (mainly 15-30 years old) which is very influential and sensitive to Western propaganda on social networks. Like his Venezuelan and Belarusian counterparts, he has no real experience of politics.

A more demanding audience sees this as a disadvantage, but for a younger audience, they have not been “compromised” in the political system.

In Russia, he is relatively unknown outside the big cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg. Generally speaking, the Russian public is more demanding than the Western public and more traditional in its preferences. This is why it appeals to a public that is not very politically active. In the West, we have a totally wrong perception of its importance on the domestic political scene. As with Juan Guaido, the West overestimates the popular support for this marginal opposition.

For the United States, the advantage of selecting challengers who are unknown to the general public is that it is easier to create myths. We have today in the West, especially in the 15-30 age group, individuals who have very little general culture, no real-life experience, not the slightest bit of knowledge about foreign cultures and who see the world through Instagram. Especially in the United States, when you see how any influencer can trigger collective hysteria, you see that it is not difficult to create heroes artificially.

The Western media present him as the “leader” of the opposition in Russia. However, even the fact checkers of the very Atlanticist French newspaper Libération, recognized that he is simply the most visible opponent. He is part of the so-called “off-system” opposition, composed of small groups often located at the extremes of the political spectrum that are too small to form parties.

In 2010, on recommendation of Garry Kasparov, Navalny was invited to the United States to attend the Yale World Fellows Program. This is a 15-week non-degree training program at Yale University, offered to foreign nationals, identified by US neocons as “future leaders” in their respective countries. It is his only credential and his only real “accomplishment.”

In Russia, Navalny advocates for the rights of small shareholders in large companies. He created an Anti-Corruption Fund (FBK), which won him sympathy in the West, but also a lot of mistrust in Russia. For his accusations against Russian personalities seem to be more driven by politics than by facts. In 2014, he was convicted of libel against Duma deputy Alexei Lisovenko. In 2016, the Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Swiss Confederation dropped a complaint improperly filed by Alexei Navalny against Artyom Chaika, son of Yuri Chaika the Prosecutor General of Russia. (In 2020, Yuri Chaika, Prosecutor General of Russia was removed from office by Vladimir Putin, for suspicions of corruption, without apparent ties to his son’s case). In 2017, the Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov, filed a complaint against Navalny for defamation and won. In 2018, Navalny lost a defamation suit against businessman Mikhail Prokhorov.

TP: How well-connected is Navalny to Western power-brokers?

JB: Navalny and his organization are largely supported financially by former Russian tycoons, such as Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Besides this, the Navalny affair is part of a US-led influence scheme that combines resources from NATO’s Center of Excellence on Strategic Communication, the UK Integrity Initiative (II), the US National Endowment for Democracy (NED), and others, such as Conspiracy Watch in France.

The II was created in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian crisis, and in November 2018, the British government confirmed that it was funding it. It is run under the aegis of the British Foreign Office (FCO), responsible for the Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6) and the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in charge of cyberwarfare, associated with this initiative. It is funded by the British Ministry of Defense and Army, the Lithuanian Ministry of Defense and NATO, and aims to combat Russian disinformation in Europe. The II uses the BBC and Reuters to promote an “official” narrative, while the II is built around private intelligence and IT marketing networks, agencies such as Bellingcat, and relies on national “clusters” made up of correspondents in each participating country.

The NED was created in 1983 in order to take over some of the CIA’s tasks, so that the latter could concentrate on more ” robust ” activities. It is an NGO (or, more accurately, a “quasi-NGO”) funded mainly by the US government and Congress. Shortly after its creation, The New York Times described it as follows:

On its website, the NED does not specify who receives its funding, but a 2006 US embassy cable from Moscow indicates that it funds Navalny’s Democratic Alternative movement. An analysis of the projects financed by the agency suggests that Navalny and his associates receive about $1.8 million per year.

Furthermore, on October 9th, 2020, John Brennan, former director of the CIA, tweeted:

Imagine the prospects for world peace, prosperity and security if Joe Biden were President of the United States and Alexei Navalny were President of Russia. We’re almost halfway there …

In short: “We are working on it!”

Without going into all the details here, Navalny as a politician is of no interest to anyone, neither in the West nor in Russia. I don’t even think that the United States seriously believes that he could be an alternative to Vladimir Putin. In reality, he’s just a small cog in a larger project to subvert Russia. Let me remind you that the objective of the United States is the disintegration (officially: decolonization) of Russia. The Navalny affair is symptomatic of a great country (the United States) that has become incapable of rising higher than its main competitors and has been reduced to seeking to destroy those who seek to surpass it. In fact, Navalny is the symbol of the United States’ weakness.

TP: He has a long history of criminality, is a convicted felon, and is serving time. What political faction, if any, does Navalny represent in the Russian political scene?

JB: Politically, his image is not very bright. In 2007, he was expelled from the center-right party “Yabloko” because of his regular participation in the ultra-nationalist “Russian March” and his “nationalist activities” with racist tendencies. He is an activist for ultra-nationalist causes. At that time, he shot a video where he mimes shooting Chechen migrants in Russia is eloquent. In October 2013, he supported and encouraged the race riots in Biryulyovo, castigating the “hordes of legal and illegal immigrants.” In 2017, the progressive American media outlet Salon, claims that “if he were American, liberals would hate Navalny far more than they hate Trump or Steve Bannon.” In 2017, the left-wing American media outlet Jacobin, even referred to him as the “Russian Trump.” In fact, as the American Foreign Policy Magazine of the American University of Princeton noted in December 2018, he emerged thanks to far-right groups, and his ideas make him more akin to what is called “populist” in the West. I suggest you watch this excellent interview with two Russian left-wing activists by Aaron Maté of The Grayzone, which illustrates the gap between reality and what our media is saying about Navalny.

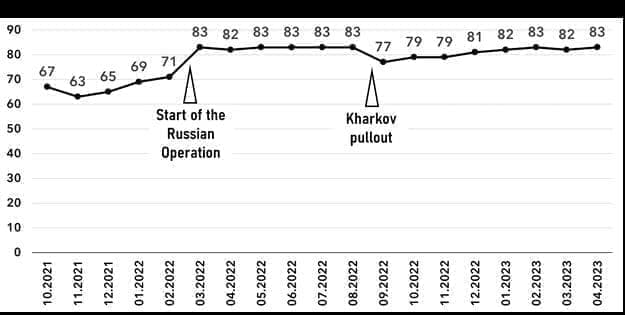

Approval rate of Vladimir Putin

Of course, our media suggest that there was “a first Navalny” and that he has since changed. Thus, in February 2021, in a TV program devoted to Navalny, a Swiss journalist claimed that “from his ultra-nationalist beginnings and his anti-migrant declarations, there is almost nothing left in Navalny.” This is pure disinformation. In April 2017, Navalny told the British newspaper The Guardian that he had not changed his mind. In October 2020, a journalist from the German magazine Der Spiegel asked him, “A party had expelled you because of your participation in a Russian nationalist march in Moscow. Have your views now changed?” Navalny replied: “I have the same views as when I entered politics.”

In order to better demonize Vladimir Putin, the West claims that he is a nostalgic of the USSR and maintains a confusion between today’s Russia and the USSR of the Cold War. This confusion makes it possible to hide the fact that the main opposition to Vladimir Putin (even if moderate) is the Communist Party. Moreover, I remind you here that the USSR included Ukraine and that the Soviet leaders who committed the most crimes (such as Josef Stalin, Leon Trotsky, Moisei Uritsky, Genrikh Yagoda or Lavrentiy Beria), were neither of Russian nor Orthodox culture.

Attempts are being made to portray Navalny as the victim of the Russian “regime” because of his beliefs and his political influence. The French media RFI suggests that he has been banned from running in the 2018 presidential election for political reasons. This is incorrect. In fact, the reasons are legal, exactly as practiced in other countries: Navalny was then serving a probation sentence in connection with the Yves Rocher affair.

Navalny began his career as an entrepreneur in the 2000s. Following a common practice in Boris Yeltsin’s Russia between 1990 and 2000, he bought up companies in order to privatize their profits (an illegal practice that led to Vladimir Putin’s fight against certain oligarchs, who ended up taking refuge in Great Britain or Israel). In the first case (Kirovles), Navalny received a 5-year suspended prison sentence.

But the most “controversial” case is the one involving the French cosmetics house Yves Rocher. It’s a relatively complex affair, with a tangle of companies and accounts, some of them offshore. The best description of the case can be found in the Yves Rocher press release and on Wikipedia (in Russian!) In short, it’s a case of embezzlement through abuse of an official position, pitting the Russian state against Oleg Navalny. In 2008, Oleg Navalny, Alexei’s brother, was a manager at the Russian Post Office’s automated sorting center in Podolsk. To facilitate the delivery of Yves Rocher products to the sorting center, he pressed the French company to use the services of a private logistics company: Glavpodpiska (GPA), which belongs to the Navalny family. There is clearly a conflict of interest and a situation of corruption, which has led to an official investigation. It is important to note here that Oleg Navalny is the main defendant, while Alexei Navalny is “only” an accomplice. This is why Oleg has been sentenced to 3 and a half years’ imprisonment and Navalny to 3 and a half years’ suspended sentence.

Oleg and Alexei Navalny appealed this decision to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), arguing that the sentence was politically motivated. Contrary to what some Western media claim, the ECHR did not invalidate this judgment, as it did not judge the substance of the case, but its form. On 17 October 2017, the ECHR issued its verdict, partially upholding the two brothers on certain points of law and concluding that the Russian justice system should pay them compensation. However, it rejected the allegation that their conviction was politically motivated (paragraph 89).

In fact, after Navalny was charged in the case against the French firm “Yves Rocher,” he was placed under probation, under the terms of which he had to report twice a month to the Russian corrections authority, until the end of his probationary period (December 30, 2020).

Navalny’s failure to comply with this obligation led to his arrest in early 2021. He had already broken this rule 6 times in 2020 (twice in January, once in February, March, July and August), but the Russian authorities had then shown leniency. As the Swiss TV correspondent in Moscow observes, Navalny “has never been sentenced to prison, unlike many other opponents.” So, despite his many offences, and contrary to what is claimed in the West, Navalny has benefited from unusual leniency. So much so, in fact, that some (conspiracy theorists) in Russia believe he is being used by the Kremlin to weaken the main opposition parties.

In order to claim that the revocation of his suspension is politically motivated, some say that Navalny was physically unable to fulfill his obligations. France 24 declared that he was unable to do so “because he was simply hospitalized in Germany.” France 5 explained that “he was in a coma,” and Swiss television (RTS) that “he was convalescing in Germany after his poisoning.” These are simply lies.

In fact, his obligation to report was suspended by the Russian authorities for the duration of his hospitalization at the Charité in Berlin. The Charité hospital doctors’ report, published on December 22, 2020, confirmed that he had been discharged from hospital on September 23, 2020 and that his symptoms had disappeared on October 12, 2020.

On December 28, the Russian prison authorities sent Navalny a warning (copied to his lawyer and press officer) to report for duty, but he ignored it.

In fact, since September, Navalny has been involved in the final editing phase of his film on Putin’s Palace. That’s why he won’t be returning to Russia until the end of January 2021. The Russian penitentiary authorities could hardly have disregarded this new offence of almost 3 months and revoked his suspended sentence. Navalny no doubt hoped to benefit once again from the authorities’ leniency; but with the broadcasting of his film, and his calls for sanctions against Russia, this was probably naive on his part… Because under these circumstances, even if the Russian authorities had wanted to show – once again – leniency towards him, this would have been incomprehensible to Russian public opinion.

TP: The documentary presents him as a serious threat to Putin. Is there something that these documentary filmmakers know which leads them to this conclusion?

JB: No, Aleksey Navalny is neither the main, nor the most important, nor the most dangerous opponent in Russia, he’s simply the most visible. He has only marginal significance in Russian politics.

Navalny has adopted the concept of “smart voting” or “tactical voting” in order to attract votes from the extremes of both the right and the left – which are not sufficiently numerous separately to field candidates in the elections. The principle of Navalny’s “smart voting” is to give your ballot to anyone but a member of the United Russia Party (Vladimir Putin’s party). It therefore works on a logic that is not based on preference, but on hatred…

The opposition associated with him is far from democratic and unified. It gathers disparate factions of the non-parliamentary opposition ranging from the extreme right to the former Stalinist communist party.

It comprises individuals who are opposed to the system, but who have neither a common vision nor a program for the future of the country. It is also a young opposition, which is informed by social networks and is relatively unstable. It is therefore essentially an opposition that seeks to overthrow Vladimir Putin without being able to provide an alternative. This explains why this heterogeneous opposition has only a very minor support in Russia. Navalny’s electoral strategy shows that he has no plans for Russia, and that the aim here is not to seek the best for Russia, but to destabilize the current government. This is why the West supports Navalny.

In fact, the Western narrative tends to suggest that the Russian population’s choice is limited to Vladimir Putin and Aleksey Navalny. This situation is very similar to what was observed in France during the presidential elections of 2017 and 2022: Emmanuel Macron was facing Marine Le Pen, the candidate of the extreme right. Then the choice of the voters was very simple: they picked the one they hated the least. In the case of Russia, the problem is even simpler, because Vladimir Putin’s popularity is considerably higher than Macron’s, while Navalny is almost unknown.

Thus, the only effect of promoting Navalny is to diminish the importance of the systemic opposition, the only one able to counter Putin. So I think Vladimir Putin should thank the Western propaganda media for weakening his opposition!

Navalny’s popularity in Russia peaked in 2020-2021, after his alleged poisoning and the movie on Putin’s alleged palace. But looking at the number of protesters across Russia at this point, one has to admit that the support to Navalny is marginal.

Navalny approbation rate

Number of protesters across Russia on January 23, 2021

TP: Then, there is the well-known incident of Navalny’s “poisoning.” Could you shed some light on this?

JB: On August 20, 2020, during his flight from Tomsk to Moscow, Alexei Navalny is taken by violent stomach pains. The flight is diverted to Omsk so that he can be hospitalized urgently. At this stage, no analysis or indication allows to determine the exact nature of Navalny’s ailment, but his spokeswoman claims that he was deliberately poisoned. Rumors on social networks about a bad combination of alcohol and drugs are quickly dismissed as “defamatory” by our media. They readily prefer – without any evidence – a more fanciful version: a poisoning with “Novitchok” ordered by Putin.

As soon as Mr. Navalny arrived at the hospital in Omsk, Russian doctors diagnosed a metabolic disorder. About ten minutes after his arrival at the hospital, they administered atropine, in order to avoid complications in case of intubation, as explained by the Russian opposition media Meduza. The problem is that since atropine is a product also used as an antidote for nerve agent poisoning, some conspiracy theorists have deduced that the doctors “knew” that he had been poisoned with Novichok, an extremely dangerous nerve agent that was allegedly used against ex-agent Sergei Skripal, in 2018.

But if this had been the case, the medical staff in Omsk would have received him with proper protective equipment! On Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Dr Aleksandr Sabayev explained that the doctors quickly realized that it was a metabolic problem and administered atropine at a much lower dose than that used in cases of poisoning.

In fact, we know what Russian doctors found in Navalny’s blood and urine, thanks to a photo of a document published by the Russian opposition website Meduza. Since no signs of nerve agent were found, our media simply did not report it!

On December 12, The Times of London, followed by the New York Post and DW, claimed that the Kremlin had attempted a second poisoning of Navalny in the Omsk hospital before he left for Germany, accusing Russian doctors of “complicity.” These media are simply liars and invent a conspiracy theory. In fact, the report of the German Charité Hospital, published in The Lancet on December 22, reveals that Navalny had a German doctor by his side in Omsk, 31 hours after the onset of his symptoms – that is, as early as Friday, August 21 – and that by the time he was transported to Germany “his condition had improved slightly.” Thus, according to the German doctors, their Russian colleagues not only stabilized Navalny, but their treatment was effective. So Navalny’s relatives and our media lied (once again).

There is little evidence to assess the relevance of the Western accusations of 2018 and 2020. The analyses carried out by the German, French and Swedish military laboratories in September 2020 remain classified and have not been published nor shared with Russia, despite its requests. As it stands, therefore, we have only the scientific results published by the doctors who treated Navalny in Omsk and Berlin, the declassified version of the OPCW report and – to a certain extent – the government’s answers of 19 November 2020 and 15 February 2021 to questions from German parliamentarians.

The analyses of the military laboratories suggest in vague terms the presence of Novitchok (but their content is unverifiable). The observations of civilian doctors tend to contradict their conclusions, while the government’s answers seem much less categorical than the media and hide behind military secrecy when the facts seem to contradict the declarations.

On August 24, the Charité hospital declared in a press release that the clinical analyses “indicate intoxication by a substance of the cholinesterase inhibitor group.” However, the doctors in Omsk had not detected any. So: conspiracy? No, not necessarily. As the opposition media Meduza says, the German doctors were looking for evidence of poisoning, while the Russian doctors were looking for the cause of Navalny’s illness. Since they were not looking for the same thing, their results were different, but not inconsistent.

In October 2020, the Swedes released the results of their analyses, noting that “The presence of [REDACTED] has been confirmed in the patient’s blood.” The name of the substance is blacked out, so we don’t know what it is. But we can assume that if it were Novichok (as Western countries expected), there would be no reason to conceal it. On January 14, 2021, the Swedish government refused explicitly to declassify this result in order “not to harm relations between Sweden and a foreign power,” without specifying whether it was Germany or the United States. So, we don’t know what’s going on, but we do know that Sweden is a country where honor is a fiction subject to political interest: already in the Julian Assange affair, the Swedish government had literally “fabricated” the rape accusations against him, according to Nils Melzer, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture.

On December 22, 2020, the analyses of Navalny’s fluids published by the Lancet as an appendix to the Charité doctors’ report is one of the few documents available containing scientific data. They allow us to draw a number of conclusions. For example, the presence of cholinesterase inhibitors could simply be explained by the antidepressants Navalny took himself, most likely in combination with alcohol. This would explain why his symptoms are totally different from those of Sergei and Yulya Skripal in 2018, who are claimed to have been victims of the same poison. It should be noted that neither the Skripals’ nor Navalny’s symptoms are consistent with neurotoxic poisoning.

Furthermore, the German doctors’ documents reveal that when the French, Swedish and OPCW took their samples – 15 days after Navalny’s arrival in Germany – his cholinesterase levels were close to normal.

At this stage, these French, Swedish and OPCW laboratories were only able to detect “cholinesterase inhibitors,” but not the substances found at La Charité, such as lithium or drugs, which were thought to have caused them to appear. In the absence of published results, we don’t know exactly what they found, but it’s likely that having no other explanation for the presence of these inhibitors, they were led to conclude that it was Novitchok.

By keeping their results secret, these laboratories had probably not anticipated that the German doctors would publish the results of their analyses. Thanks to the latter, the hypothesis that Navalny was the victim of accidental poisoning appears more likely than deliberate poisoning.

Navalny must obviously have known this, just as he must have known that these results were going to be published; and it was probably to disqualify their conclusions that, the day before the Lancet article was published, Navalny staged his telephone conversation with an “FSB agent.”

TP: Is Navalny yet another “anti-Putin” tool of the West? Or is the documentary simply capitalizing on the emotionalism surrounding the war in Ukraine?

NB: In fact, since the early 1990s, the central tenet of American strategy has been to maintain its supremacy on the international stage. This is the Wolfowitz Doctrine. Until the early 2000s, the United States had the advantage of having as an adversary a Russia rebuilding after the fall of communism, and a China that did not yet have the economic importance it has today.

The Bush administration’s withdrawal from disarmament agreements in 2002 created mistrust in Russia. This explains why President Putin is seeking to assert his country’s position and its right to security. This led to Vladimir Putin’s speech in Munich in 2007, which the United States took as a declaration of war.

This situation has led the United States to adopt a destabilization strategy that includes support for non-systemic opposition.

The American strategy against Russia is very comprehensive and includes a wide spectrum of means. It is described in detail in a set of two documents drawn up by the RAND Corporation, the Pentagon’s main think tank: Extending Russia: Competing from Advantageous Ground and Overextending and Unbalancing Russia. The war in Ukraine is the most visible since February 2022, but there are also the tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Transnistrian region, the destabilization of Syria, etc. The support for Navalny is part of this overall strategy.

The paradox is that Russia got involved in Ukraine to protect the people of Donbass, which is a very popular cause in Russia. The same goes for Crimea, which was an autonomous entity just before Ukraine became independent in December 1991. Moreover, Vladimir Putin’s popularity, already very high, has been further boosted by the terrorist attacks carried out in Russia by Ukraine and supported by all Western countries.

So, Navalny is part of a comprehensive effort to discredit and ultimately to isolate Russia on the international stage. However, the impact of this campaign on the internal situation in Russia is debatable. The patriotic sense of the Russian population is very high and even Navalny’s partisans tend to support the government. For instance, I noticed that non-systemic opposition websites very often show different views from those of the West. Although there is still a domestic opposition to the Special Military Operation, we can see that it remains very stable and marginal.

TP: Thank you so very much for your time. Any last words?

JB: It’s ironic to see European politicians taking up the cause of Navalny, an extreme right-wing nationalist, who approves of the annexation of Crimea (and declared in the pro-western Moscow Times that he wouldn’t give it back if he came to power ), who has never expressed a concrete project for Russia, who has sought to enrich himself through embezzlement, and who represents none of the values that Europe claims to defend!…