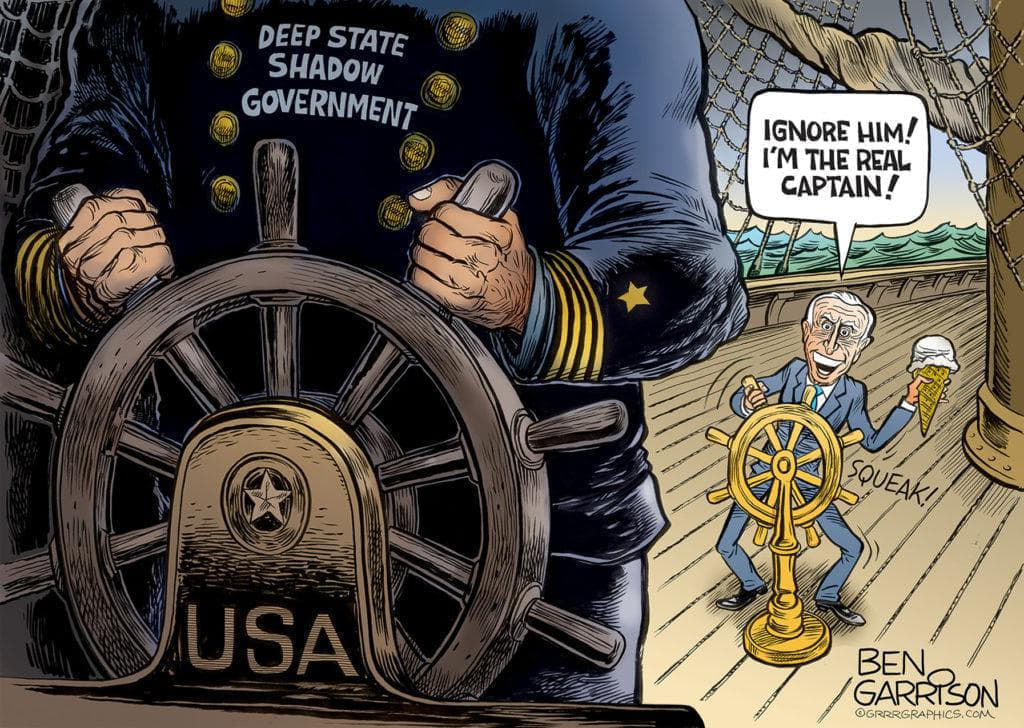

The “managerialization” of the State, imposed with arrogance after 1989, in fact corresponds to its neutralization or, more precisely, to its subsumption under the economic moment that led to the materialization of Foucault’s prophecy: “one must govern for the market, instead of governing because of the market.”

The inversion of the traditional power relationship ended up causing the transition from the market under State sovereignty to the State under market sovereignty: in complete liberal cosmopolitanism, the State is now a mere executor of market sovereignty.

Ceremonially celebrated by the new post-Gramscian Left and by its program (more and more clearly coinciding with that of the liberal elite), the abolition of the primacy of the State has contributed to liberate not the dominated classes, but the “wild beast” of the market.

In the era of the State with limited or dissolved sovereignty, the prerogative of superiorem non recognoscens is acquired in a stable and direct manner by the globalist elite of the neofeudal lord, which exercises it through organizations reflecting its interests—from the ECB to the IMF. The planetary economic has conquered the status of a power that does not recognize anything as superior.

The aforementioned private and supranational entities annihilate any possibility of addressing with public resources the dramatic and pressing social issues linked to labor, unemployment, growing misery and the erosion of social rights.

In the absence of the eticizing power of the State, the liberal-libertarian plutocratic elites openly preach and quietly practice, in their own interest, wage moderations, control of public accounts and, naturally, the sanctioning of eventual non-compliance. At the same time, they can recover everything they had lost through class conflicts, id est everything positive that in the Novecento—the century of labor and social conquests, and not only of “political tragedies” and genocidal totalitarianisms—the workers’ movement had managed to achieve: from the entry of law into the workplace to the formation of trade unions, from free education for all to the foundations of the welfare state.

Moreover, classist economic fanaticism can easily use the ideologies of the past, linked to ignominiously failed political projects, as a negative symbolic resource to legitimize itself. It can now present itself as preferable to any previous political experience, or liquidate a priori any project of world regeneration and any utopian-transforming passion, immediately assimilated with the tragedies of the twentieth century.

The proclamation of the End of History was raised, since 1992, as the ideological compendium of the world today entirely, subsumed under capital. Emblem of the destinalist philosophy of the capitalist progress of history, it succeeded in installing in the general mentality the need to adapt to the new power relations. And all this, moreover, with the awareness—cynical or euphoric, as the case may be—of having reached the end of the Western historical adventure, completed with the universal freedom of the planetary market and with humanity reduced to the condition of solitary consumer atoms, with an abstractly unlimited will to power and concretely coextensive with respect to the available exchange value.

Functional for the general alignment with the imperative of ne varietur, the postmodern demystification of the great meta-narratives proceeded hand-in-hand with the imposition of a single grand narrative permitted and ideologically naturalized in a single perspective admitted as true: the worn-out storytelling and the abusive liberal vulgate of the destinalist End of History in the post-bourgeois, post-proletarian and ultra-capitalist framework, inaugurated with the fall of the Wall and with the real cosmopolitization of the capitalist nexus of force.

Suffice it to recall here, as a concrete example drawn from our present, the role of the so-called “Non-Governmental Organizations” (NGOs). These, together with multinational and deterritorialized companies, have challenged the predominance of States. Behind the philanthropy with which these organizations claim to act (human rights, democracy, saving lives, etc.) is hidden the naked private interest of transnational capital.

Non-Governmental Organizations, in reality, claim from below and from “civil society” the “conquests of civilization,” the “rights” and the “values” established from above by the masters of the levelling globalism that “per sé fuoro” (Inferno, III, v. 39), the new financial conquerors and the custodians of the great business of the supranational market under the hegemony of private capitalist speculation.

Such conquests, rights and values are, consequently, always and only those of the competitive global class, ideologically smuggled as “universal”: demolition of borders, overthrow of rogue states (i.e., of all governments not aligned with the unipolar and American-centric New World Order), encouragement of migratory flows for the benefit of corporate cosmopolitanism, de-sovereignization, deconstruction of the pillars of bourgeois and proletarian ethic (family, trade unions, labor protection, etc.).

From this perspective, under the humanitarian veneer of NGOs, we discover the Trojan Horse of global capitalism, the tableau de bord of the cosmopolitan elite, with its ruthless fundamental rule (business is business) and its assault on the sovereignty of States.

If they are not analyzed according to the scheme imposed by the hegemony of the financial aristocracy, Non-Governmental Organizations reveal themselves as a powerful means to circumvent and undermine the sovereignty of States, and to implement point by point the globalist plan of the ruling class, in search of the definitive liberalization of the political regulation of sovereign national States as the last strongholds of democracies.

The clash between Non-Governmental Organizations and the laws of national States does not hide, as the masters of the discourse keep repeating, the struggle between the philanthropy of “love for humanity” and inhuman authoritarianism; on the contrary, we find the war between the private dimension of the profit of transnational groups and the public dimension of the sovereign States under their siege.

Specifically, for those who venture beyond the glassy theater of ideologies and assert the volonté de savoir of Foucauldian memory, on the horizon of globalization as the new scenario of the cosmopoliticized conflict between master and servant, Non-Governmental Organizations appear as the ideal instruments for the imposition of a political agenda matured outside any democratic process and exclusively protective of the concrete interests of the hegemonic class.

The latter, by the way, using the diligent work of the anesthetists of the spectacle, defames as “sovereigntist”—the umpteenth fraudulent category coined by the neo-language of the markets—anyone who does not definitively say goodbye to the concept of national sovereignty. A bastion of the defense of democracies developed within state spaces still resistant to the New World Order (which is post-democratic to the same extent that it is post-national), the objective is that the very notion of national sovereignty be ideologically degraded to an instrument of aggression and oppression, of intolerance and xenophobia.

Diego Fusaro is professor of the History of Philosophy at the IASSP in Milan (Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies) where he is also scientific director. He is a scholar of the Philosophy of History, specializing in the thought of Fichte, Hegel, and Marx. His interest is oriented towards German idealism, its precursors (Spinoza) and its followers (Marx), with a particular emphasis on Italian thought (Gramsci or Gentile, among others). he is the author of many books, including Fichte and the Vocation of the Intellectual, The Place of Possibility: Toward a New Philosophy of Praxis, and Marx, again!: The Spectre Returns. This article appears courtesy of Posmodernia.

Featured: Corrupt Legislation, mural by Elihu Vedder, in the Lobby to Main Reading Room, Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C.; painted in 1896.