An immortal figure, except for his political career, Abel Bonnard (1883–1968) was a member of the Académie française and one of the most popular writers of the interwar period, prompting Céline to call him “one of the finest French minds”. His prolific output includes poetry, travelogues, novels, biographies and a section in the tradition of the French moralists of the Classical Age, including his essay L’Amitié (Friendship), published in 1928.

In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle devotes two chapters to the polysemic meaning of friendship. Philoi thus goes beyond the simply “friendly” concept we are familiar with, to mean sociability and reciprocal affection. It covers the relationships that animals, lovers (as Tristan sings to Isolde at the home of Marie de France: “Bele amie, si est de nus:/ Ne vus sans mei, no je sanz vus“), various family members. Aristotle not only explains these different relationships, but also distinguishes, as Cicero and Montaigne would later do, three types of friendship, which are different in nature and not simply in degree: the first, the most vulgar, is that based on interest and therefore usefulness; next comes that which is akin to pleasant companionship, but which is only the image of true friendship; the third, which relates to the good and enables the fulfillment of virtue between good men.

True friendship, which, unlike the accidental character of “familiar relations formed by some circumstance or utility” (Montaigne), is immutable and can only be born among virtuous men, “friends by virtue of a certain good and a certain resemblance” (Aristotle). This friendship is that of the absolute choice of a being in whom we recognize our similarity in terms of virtue, which is just as beneficial, whether it emanates from us or from another man of value, the friend being for Aristotle “another self.”

However, if Aristotle’s whole question of friendship is to be placed within the broader framework of a reflection on the Good, this notion may sound barbaric to modern ears. Indeed, the history of philosophy since Antiquity has witnessed a gradual shift away from the idea of a transcendent Good, independent of man and objective, gradually giving way to the notion of freedom. For Hegel, the spirit becomes aware of its own nature through history, and by becoming conscious, by moving from the in-itself to the for-itself, humanity gradually liberates itself: “To make the external world everywhere conform to the concept of freedom once recognized, such is the task of the new times,” were the last words he uttered in his very last lecture. The cardinal value of our time has thus become Freedom, i.e., man’s ability to be an active subject in history, to do good as well as evil, to have “within himself the possibility of both the absolute something and the absolute nothing” (Weininger, Sexe et caractère, 1903).

Abel Bonnard takes note of this change and now understands that the men who can lay claim to friendship are those who are similar in terms of freedom rather than virtue; he writes in Les Modérés: “Those who have really done something must be noble; they cannot be pure.” The author strives to defend an aristocratic conception of humanity, in which only a few great souls can be differentiated, “a small number of beings without any relation to all the rest, noble, superior or charming” (L’Amitié). In this world, where men are abstractly reputed to be free and equal, Abel Bonnard is quick to remind us that an elite does exist, a community of equals among the unequal, of men running the gauntlet with Rimbaldian “free liberty,” i.e., taking it violently in hand. Nobility of soul requires us to be absolutely modern, to act out this passage from Happiness to Freedom: “But why regret an eternal sun, if we are committed to the discovery of divine clarity—far from the people who die in the seasons” (Rimbaud). All men are now free, but only a few know how to make themselves worthy, and those who are worthy can earn that august passion that is friendship. At the exact opposite end of the spectrum are the literal and botanical antipodes, the clumsy onlookers, embarrassed by silly qualities of psychological characterization. As welders of trivialities, they rely on adventitious elements such as occupation, “passions” and habits to compose their relational circles, all of which have nothing to do with a man’s deeper character.

Only true friendship can exist today between men who are fundamentally free, explains Bonnard, between what we will call distinguished men, both by their eminently superior character and by their delicate manners and refined tastes. The character of such men is complex and requires several common traits.

An “intimate richness” must pre-exist friendship between “spirits of the same rank,” for how can one extend oneself into the world without first having delved into oneself, without having plumbed the depths of one’s solitude? Men in the crucible of experience have acquired an autonomy that is the first impulse of freedom, since to be free is to be able to begin to make sovereign decisions about one’s life. It is because a man has differentiated himself from the masses that he can have an original vocation in the world, and it is in this that he can be a regular friend, with whom we can finally find a spirit to our measure that can exalt us, reminding us of Theognis’ words in his Sentences, “Nobility of soul is learned from noble souls.” In this sense, Bonnard sees in leisure the possibility of “completing ourselves” and gaining in subtlety so as to be able to communicate something to our fellow man: without deep inner work, without distinction, without introspective impulse, without radical originality, speech is reduced to impudent chatter. The friend has something of himself to offer, his otherness; and this is where man can begin, Bonnard tells us, echoing Otto Weininger a few years earlier: “Male friendship is a trade based on the sharing of the same idea or the same ideal; in other words of something that unites them without ceasing to belong to each of them in particular.” That said, the beginning of friendship in Bonnard’s work is not essentially a matter of ideas, but takes place well upstream of the “commerce of intelligences.” Beyond mutual sympathy, the two friends must have a similarity of nobility and grandeur, of instincts and tastes: they must be able to sense in each other the nobility of the race. The original potential of friendships thus comes primarily from compatible characters.

Perhaps this is what the quest of our lives here on earth is all about: to find worthy company with men who, among other eminent qualities, share the most incoercible: a taste for the absolute. In Aurélien, Aragon writes unforgettable pages on this taste for the absolute that embraces Berenice, plunging her into a vertigo that “is accompanied by a certain exaltation, which we will recognize at first, and which, always exerting itself at the sharp point, at the center of destruction, risks making unwary eyes mistake the taste for the absolute for the taste for unhappiness.” But above all, those who are pierced by the absolute are in search of “the embodiment of their dreams, [of] living proof of greatness, nobility, the infinite in the finite,” and escape the vicissitudes of the centuries. Distinguished men with a taste for the absolute are the shooting stars of this world: they are men unaffected by the turmoil of the centuries, atemporal men, pilgrims of the Absolute with an imperishable character; these are the monads we must try to grasp if we are to enliven humanity. Let us become demiurges, spewing the lukewarm and the apocryphal whites; let us find the men of our race, with whom we share the same burning fire; let us rummage through the apparent mire without reluctance to “look in the scum for someone rare and exquisite.” Happiness, a backward clown, drags its feet and begs, but what does it matter to us as long as there are still works to freely aspire to.

As we have just seen, the distinguished man, polished by the centuries, is above all a profoundly unique man, but not a lonely one. It is because he has understood the limits of his own monadic finitude that the distinguished man seeks to confront other souls, for “as soon as a man reaches a certain inner richness, he feels that what he has done does not express his whole nature” (L’Amitié); and so he must confront reality. As Simone Weil teaches us in the lines devoted to friendship in Formes de l’amour implicite de Dieu (Forms of God’s Implicit Love), this reality, the place where we encounter exteriority, is synonymous with the materialization of contradictions. “Friendship is a supernatural harmony, a union of opposites,” she tells us, namely “the preservation of the faculty of free consent in oneself and in the other,” leading to equality. To project himself into the world, man must be differentiated, freely disposing of himself. He must be both a stranger to himself and an inhabitant of the world, enriching himself without being distorted by it. Abel Bonnard sprinkles his short essay on friendship with aphorisms and ties these contradictions together laconically: “Friends are loners together,” which should be read with Simone Weil in mind: “There is friendship only where distance is preserved and respected.” As Aristotle was fond of reminding us, man is a sociable being, and so he cannot do without a vital attachment to that other himself: friendship takes on its full meaning when we live together.

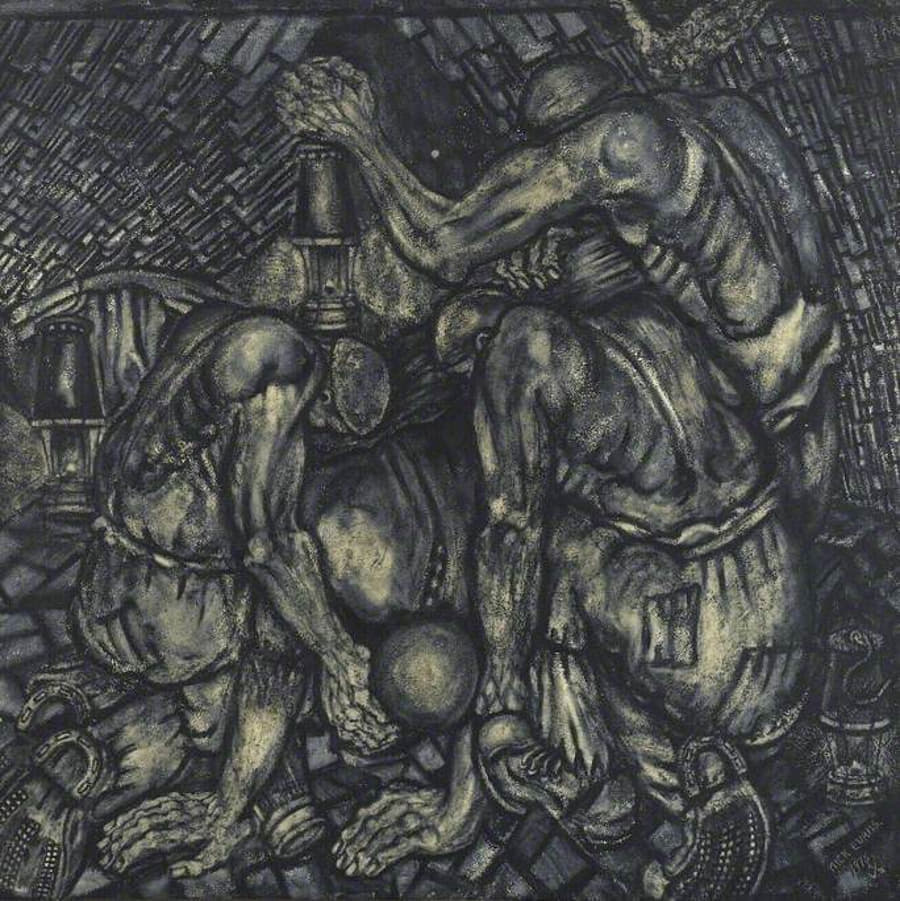

For Aristotle, living is initially assimilated to feeling and thinking, but this world of potentiality must be embodied: “Power is conceived by reference to action, and it is in action that the essential lies” (Nicomachean Ethics). Friendship in power must be actualized, that is, man must manifest his inner life through action, by committing his own freedom to the world. Friends are above all men who are ready to compromise themselves, and it is by giving themselves to the world that they can give life to their sensibility and learn: “When someone enchants us with his rich and profound experience, it is not the case to demand from him a spotless neatness. If he had wanted to keep it, he would not have learned so much. The most virtuous follow the straight path, which is, by definition, the one that passes through the fewest places. The purest cannot also be the richest” (L’Amitié).

Friendship between sovereign men unfolds both in space and in time, i.e., within a historical framework. Aristotle places friendship precisely within a communitarian and political reflection (“the deliberate choice of life in common is friendship; the end of the state being therefore the good life, all this exists only for this end”, Politics) on the different types of government, which he structures in a ternary fashion (kingship, aristocracy and republic, with their degenerate forms respectively: tyranny, oligarchy and democracy). The types of friendship differ according to the political regime, with those allowing the most friendship obviously being preferable. Contrary to Aristotle, who suggests that, among decadent forms, democracy is the one that best allows for friendship in that it brings together a priori more equal subjects, and to Derrida, who fantasizes about a future democratic promise in Politiques de l’amitié, Bonnard realizes that democratic egalitarianism does not allow for friendship because it does not understand the differentiation of beings: “In a world without elites, there are no more friendships.” In addition to the egalitarian fad that disregards any qualitative differences between individuals, democracy has given rise to “friendships” based on self-interest.

We find eloquent illustrations of these utilitarian friendships in Barrès’ Romans de l’Énergie Nationale, which depicts the various financial and parliamentary compromises of democracies, and which undoubtedly influenced Bonnard. Thus, in Les Déracinés, an impossible understanding is born, a heartbreak between the seven young men who, freshly landed in Paris, meet in front of Napoleon’s tomb at Les Invalides to seal their destiny: “Destiny, duty, culture; these are the three terms in which Sturel, Saint-Phlin, Rœmerspacher were to sum themselves up. Suret-Lefort, for his part, was thinking of appearances; Racadot and Mouchefrin, of pleasure; Renaudin, of food.” In fact, since “all individuality poses as the enemy of the spirit of community” (Weininger), any true friendship in a democratic regime has to be transgressive: it has to be completely at odds with the established bourgeois order, with the cozy little nest in which it is easy to let oneself snooze comfortably in the middle of winter. Let us go even further: if friendship is automatically corrupted in a democratic regime, as Bonnard argues in Les Modérés, it is precisely because it is the only democracy worth having, being a “differentiated egalitarian social order,” being that of men free and equal in nobility, who, by their height, strike down the bleating voters. In his Éloge de l’ignorance, Bonnard castigates republican, universalist, egalitarian and scientistic (and therefore reasoning and aspermatic) education, which produces a “sinister dearth of men.” Against this, Bonnard aspires to a Nietzschean cultural revolution, which aims to bring passion, instinct and action to the fore rather than cold reason and pure intellectualism, for man is made to “poetically sublimate and transfigure the world and its secrets, not to elucidate them.”

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche stresses the “fundamental antagonistic relationship” between man and woman. This book was bound to exert some influence on Bonnard’s contradicter, who is adamant about the impossibility of women’s access to friendship. For him, the empire of friendship is unconquerable for them, because the planes of abstraction and conceptualization belong to the male mental universe. Clearly, women’s intelligence does not play a comparative role to that of men; rather, it is used quite differently: women (to be understood here, as with Weininger, as the absolute feminine principle and not as empirical women) are immersed in the world and its intrigues, and do not, unlike men, attempt to abstract themselves from it using their intellectual faculties. The friendship that can be attributed to women between themselves is also a deception and stops at the stage of pleasant companionship, since women do not walk on the crest of ideas and cannot get rid of the specter that love constitutes for them. “Friendship” for women, even when it is a matter of masked rivalry, can only take on, ironically, the finery of intimacy, the discovery of its exposure and sexualization: “Women reduce the other to his sexuality… What interests a woman in a human being is first and foremost his love affairs” (Weininger). This permanent cult of the present, this impossibility of historicization, this subjection to love, is what women lack in order to build a friendship, requiring temporalization, constancy and projection. For Schopenhauer, women are much more frontally in the present than men, “the being of instantaneity, of immediacy,” and “all that is present, visible and immediate, exercises over them an empire against which neither abstractions, nor established maxims, nor energetic resolutions, nor any consideration of the past or the future, of what is distant or absent, can prevail” (Essai sur les femmes).

Friendship between men and women is also a chimera, as this same friend explains, since friendships between the sexes can only be the cover-ups for love, its bastard forms: they “are nothing, or they are the contained, attenuated, weakened, unconscious or, by themselves, modest and quiet expression of a loving feeling.” In this sense, friendship can only be a subtle declension, half-confessed and avowable, which has more to do with pleasant Aristotelian companionship mixed with a fine amorous projection, as is particularly clear with the case of “men who, under the name of friends, are only former suitors, reduced to modesty.” These friendships, while necessary to the flow of a life that occasionally includes moments of entertainment, cannot touch the “deep life,” enriching friends with a consequent contribution. True friendship does not consist in the shameless unveiling of oneself, nor can it accommodate the shenanigans of lies. Worse still, such habitual friendships can provide support for a man’s self-love, as if he were donning “the gaudy garb of the young leading man,” and for the woman, whose power of seduction is always to be tested, among her friends whom she would consciously or unconsciously assimilate to a flock of courtiers. Yet friendship cannot be a place for equivocation: “love has at least that in itself, that one is forced to prove oneself, instead of these so-called friendships being affections without expense.” Bonnard, gathering his thoughts, synthesizes as follows: “Those of our friends whom we love best are perhaps only women we could have loved. By the subtlest of artifices, we delude ourselves into believing that we escape with her from the eternal intrigue of the sexes.”

If friendship between men hovers far above love, friendship between men and women can never fully detach itself from it; in detumescence, it becomes a bastard form of it, while beyond it, an amplification of friendship between a man and a woman can only transmute into love. It is precisely in the bosom of love that friendship between a man and a woman can be fully tasted; so it is no coincidence that, after the developments we have just attempted, Aristotle equates friendship between husband and wife with the aristocratic regime. It is a tribute to love to find friendship in it, for it is a great pity, Bonnard teaches us, that most lovers love each other in order to escape the idea of friendship, and worse still, that most lovers love each other without friendship. Throughout Les Poneys sauvages, Déon portrays “friendly lovers” following a set course: Georges, a traveling journalist, and Sarah, a wandering Jewess, masculine woman, inveterate seductress, delirious soul, eternally elusive. Tenderness is often taken for granted between the lovers, but supreme love cannot do without a deep friendship, woven like a nearby reclining bed around them: “After embracing as if to perish together… after having given each other everything, they were charmed to be able to say everything to each other.” If the human is found at the juncture of man and woman, perhaps the androgynous alone can be resurrected in love, like Tristan finding Isolde, or René and Florence uniting to perfection in Toledo in Comme le temps passe.

Love or friendship, both presuppose an impossible perfect unity, which remains the prerogative of the divine. Bonnard’s conclusion, “true poetry, on the contrary, is to always increase ourselves, without ever being sufficient, and to sink into ourselves without excluding ourselves from the Universe,” echoes Simone Weil’s lines on friendship: “Pure friendship is an image of the original and perfect friendship which is that of the Trinity and which is the very essence of God. It is impossible for two human beings to be one, and yet scrupulously respect the distance that separates them, if God is not present in each of them. The meeting point of parallels is infinity.”

Théo Delestrade writes from France. This articles appears through the kind courtesy of PHILITT.

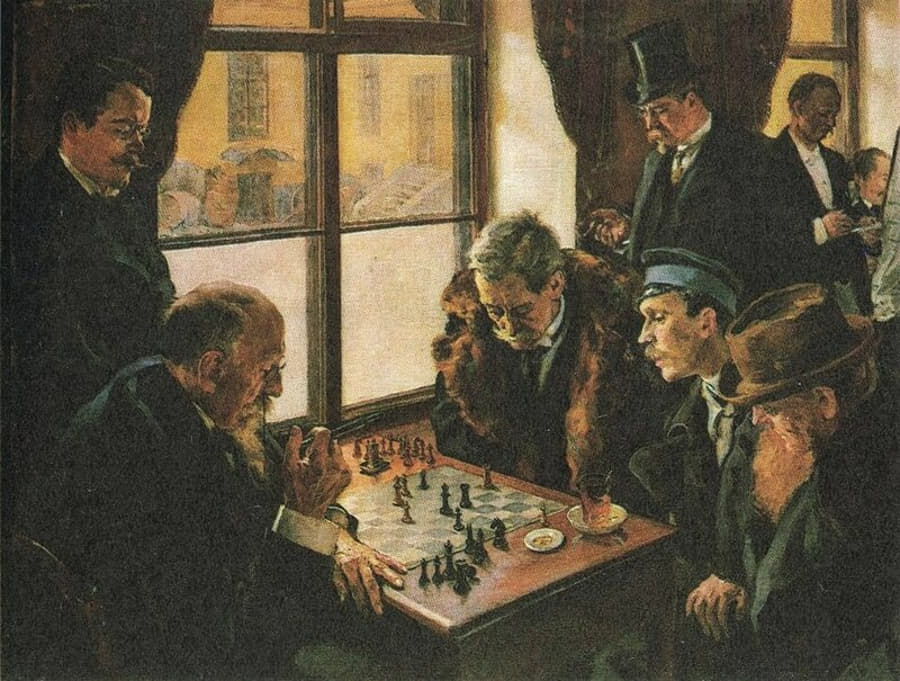

Featured: Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape, by Thomas Gainsborough; painted ca. 1750.