1. A Brief Intellectual Biography

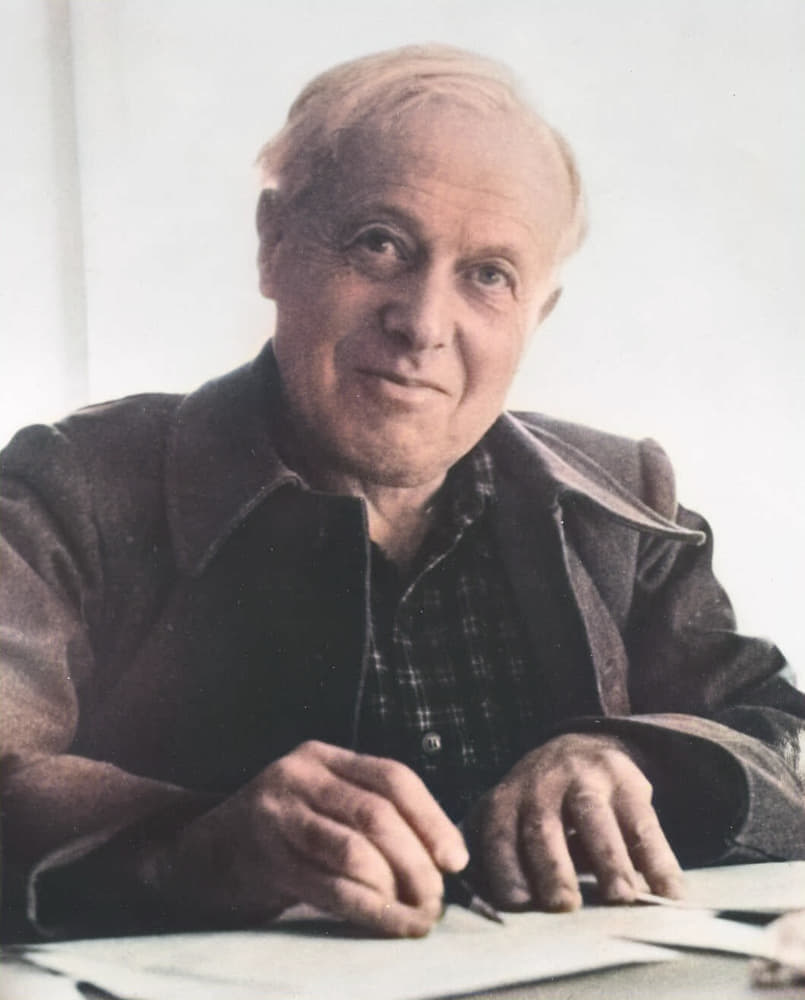

I wrote the second part of this essay for the annual meeting of the Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy Fund, on the Commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the death of the German-American thinker, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (1888—1973). That part was originally written for those who already know of his work, which is a very small group indeed. The voice it is written in reflects not only the circumstances and interests of the audience for whom it was written, but it reflects the emphasis, which I think might be of value to those who know nothing of him. Hence for those who have never heard of Rosenstock-Huessy before, a few biographical details may be warranted.

He was born in 1888 into a family who were of Jewish blood but had no interest in their tradition. His mother was as little moved by her son’s conversion to Christianity as she was by the tradition of her ancestors. Of his conversion, Rosenstock-Huessy said that there was no road to Damascus; his baptism seemed a natural progression from his interest in philology and history, and he simply thought that every word of the Nicene Creed was true. He received a doctor of laws at the age of 21, with the inaugural dissertation, “Landfriedensgerichte und Provinzialversammlungen vom 9.-12. Jahrhundert, (Courts of Peace and Provincial Assemblies from the 9th to the 12th Centuries).” And few years later, he completed his Habillitation (the German degree that is usually a prerequisite for becoming a university lecturer), with the deesertation, “Ostfalens Rechtsliteratur unter Friedrich II (East Westphalian Legal Literature under Friedrich) .”

By the age of 24, he was a private lecturer, teaching German Private Law and German Legal History at the University of Leipzig, before joining the German war effort. He served as an officer, and while fighting in the Battle of Verdun he had, what he himself called, a vision of the providential nature of war and revolutions and their indispensable role in making us and the world we now inhabit. That idea would first take preliminary form in 1920, in the work, “Die Hochzeit des Kriegs und der Revolution (The Wedding of War and Revolution).” This was followed by more complete versions, Out of Revolution: Autobiography of Western Man (1938) and Die europäischen Revolutionen und der Charakter der Nationen (The European Revolutions and the Character of Nations) (1951).

These works focussed upon the unity of the European revolutions, which he derived from what he saw as the first total revolution in the West—the Papal revolution, an event involving a complete rejuvenation of the Church that led to Pope Gregory VII’s excommunication of Emperor Henry VI over the practice of lay investiture. The popular support for the Gregorian position was perhaps most evident in the Church ridding itself of married clerics. The central argument of the works was that the Western revolutions that followed—the Italian Revolution (the Renaissance), the German Revolution (the Reformation), the English Revolution, the American Revolution (which he depicts as a half-way house revolution), the French and Russian Revolutions—were not only decisive in the formation of the modern European nations and their character, but gave birth to the social materials and commitments/ the faith that would flow into the world wars, and thereby draw the entire world into an unstable unity.

The story he tells is one in which providence (and not the wills of men) forces us into a condition where we must confront each other in dialogue, draw upon our respective traditions as we seek to navigate a common future—or what he called a metanomic society—if we are to achieve any lasting peace. A metanomic society is not to be confused with the progressive, globalist order that asphyxiates living spirits in conflict so that they may all be presided over by an elite of the good, the true and the beautiful—and the extremely wealthy. Rather it is one of persistent tensionality, as nations and peoples meet at the crossroads of a universal history of faith and war and revolt (sin and disease). On that cross road we encounter the various pathways and epochs (“time-bodies”) opened by founders who often stand for inimical life-ways, and yet we have to find a way to stand or perish together.

The works on revolution were themselves but parts of a more complete attempt to outline his vision of a metanomical society, Die Vollzahl der Zeiten (“The Full Count of the Times”), which would almost take him fifty years to complete. There he formulates the problem confronting the species, as one of making contemporaries of distemporaries—for we all come out of different “times.” Die Vollzahl originally appeared as the second volume of the work published in 1956—1958 as Soziologie, and has more recently appeared under the title he intended as, Im Kreuz der Wirchlichkeit: Soziologie in 3 volumes (Vollzahl appears as volumes 2 and 3 in that edition.) The two parts of the work are divided into one dealing with spaces—it is called Die Übermacht der Räume, which Jurgen Lawrenz, Frances Huessy and myself have translated and edited as The Hegemony of Spaces. The second, as I have indicated, deals with “the times.” The plurality adopted in the titles is important—for much of what Rosenstock-Huessy sees as destroying the human spirit is the adoption of the metaphysical and mechanical ideas of time and space as blinding us to living processes and the role of spaces and times in our lives, especially the opening up new paths of the spirit, involving a new partitioning of time.

The first volume of Soziologie/ Im Kreuz der Wircklichkeit is devoted to laying down Rosenstock-Huessy’s methodological critique of what he sees as the philosophical disaster that has culminated in what he calls, in the culminating section, “The Tyranny of Spaces and their Collapse,” the triumph of the Cartesian dissolution of all life into mechanical space paired with Nietzsche’s aestheticization of life which leaves the more fundamental tyranny untouched. That tyranny comes from the failure of a world increasingly dependent upon professionals devoted to ideas and ideals to understand the living powers of social cultivation and us substituting abstractions for living processes. The key idea of that volume is that play had always been conceived as a preparation for life, by sequestering spaces for play which enable people to focus upon the requisite undertaking we are engaged in. Play enables us to develop a more controlled, a more distanced and hence abstract understanding of life. It also aids us in developing our focus and capacities that may assist us in the tribulations that befall us in “real” life. Play is the species’ greatest source of education. It is thus not a mere afterthought to survival but as intrinsic to our nature as to our social formation and history.

Those familiar with Johan Huzinga’s Homo Ludens will be familiar with how play forms the basis of reflective life, though I think Rosenstock-Huessy makes this the basis of sociology, and human social roles, and by doing so does far more with it, especially in how he identifies the way in which the reflective consciousness has generally downplayed the more primordial social emotions and priorities required for developing pathways of life, in which we find our place and commitments in the world. Lifeless essences—“the individual,” “man,” “free will,” and such like—which can be moved about by the mind of the intellectual on a blank canvas of mental space are treated as real, while real forces of shame, admiration, gratitude, behests, affirmation, negation (I am taking a random selection from powers Rosenstock-Huessy denotes within a larger sociological breakdown) whilst still socially operative are not even noticed by most scholars and researchers.

It would be remiss of me not to mention another preliminary aspect of his intellectual biography. Prior to the First World War, Rosenstock-Huessy was the teacher of the most important Jewish philosopher of the twentieth century, Franz Rosenzweig. Their friendship and his lectures led to Rosenzweig considering to follow his cousins (the philosopher, Hans and author, Rudi Ehrenberg) and Rosenstock-Huessy into the Christian faith. At the last minute, after attending a Yom Kippur service, as a farewell gesture to the faith of his ancestors, Rosenzweig decided that he would “remain a Jew.” Rosenzweig’s “conversion” experience led him to seek out Rosenstock-Huessy again and enter into a dialogue about Christianity and Judaism.

In 1916, the two friends engaged in a heated but brilliant exchange, in which each defended his own faith and criticized that of the other. The correspondence has been translated into English and edited by Rosenstock-Huessy in Judaism Despite Christianity. It is the most important Christian-Jewish dialogue ever written. Rosenstock-Huessy left Germany as soon as Hitler came to power, but he did return in 1935 to help launch Rosenzweig’s Collected Letters. Rosenzweig, by then was deceased, and the correspondence between him and Rosenzweig played a special part in that collection. In my book, Religion, Redemption, and Revolution: The New Speech Thinking of Franz Rosenzweig and Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, I have written the only extensive account of the intellectual relationship between Rosenzweig and Rosenstock-Huessy, that draws attention to how they believed that they were, in spite of irreconcilable differences of faith, fighting on a common front against the kind of abstract and philosophical thinking that has dominated the West and is now destroying it. Both, in different ways, undertook to explicate the power of their respective traditions and what those traditions uniquely brought to our understanding of experience. Whereas Rosenzweig has a small audience in the academy (and I make no excuse for the fact that I find the academic reception of Rosenzweig in the US and Germany to be a bowdlerisation of his thinking so he can fit the “ethical” and “political” prejudices that now dominate the academy), Rosenstock-Huessy is almost completely unread today.

Before coming to the United States Rosenstock-Huessy had played an important role in seeking to build bridges between Protestants, Catholics, and Jews. He wrote, Das Alter der Kirche (The Age of the Church) with Joseph Wittig and collected a mountain of material arguing against Wittig’s excommunication—the excommunication would subsequently be overturned. He also played a leading role in the formation of the Patmos publishing house and the setting up of the journal Die Kreatur, both ventures in religious cooperation directed against the forces of resentment that were fuelling the Marxist and Nazi ideologies. In addition to his academic work and writing, after the First World War, he worked for a while with Daimler Benz, editing a magazine for the firm and its workers. He would also play a leading role in fostering cooperation between students, farmers and workers. In the United States he would continue that aspect of his work by helping set up Camp William James, which has been said to have inspired the Peace Corps. He was also the first director of the adult education initiative of the Academy of Labour in Frankfurt, and then between 1929 and 1933, vice-chairman of the World Association for Adult Education. I mention this just to emphasize that just as Rosenstock-Huessy did not belong to one discipline, (he was not a legal scholar, philosopher, sociologist, historian, nor philologist, classicist, nor theologian) yet every work he wrote storms through these and other disciplines, he was also not simply an academic. Like Goethe, whom he quotes incessantly, his focus was life itself, not just ideas.

Admired by Martin Buber, and Paul Tillich with whom he corresponded, and W.H. Auden, who wrote a preface to his I am an Impure Thinker, but unlike so many other German emigres to the US, settling in Dartmouth, he had no doctoral students, and was essentially living and writing as an exile.

2. Commemorative Essay

Unlike every other essay I have ever written on Rosenstock-Huessy, this commemorative one is written for an audience who already knows who he is. Each member of this audience has encountered Rosenstock-Huessy in his or her own way: some are family members, some were his students, others, like myself, simply stumbled onto him. Each member of the audience also has his or her own reasons for how Rosenstock-Huessy’s teachings have mattered in their own lives. Further, there is also a common desire to see his work gain a wider readership and larger influence.

In spite of the indefatigable efforts of Freya von Moltke, Clinton Gardner, Harold Stahmer, Frances and Mark and Ray Huessy, Lise van der Molen, Michael Gormann-Thelen, Eckhart Wilkens, Norman Fiering, Russ Keep, and many, many others (I apologize to the many I have not included here) to gain the audience his great corpus deserves, he remains almost unknown to university professors and teachers and their students, as well as the rest of the population. The efforts of his family, former students and friends have also contributed to preserving his work digitally, which means that scholars in the future have a vast treasure trove of materials to explore, if ever his name does catch fire. Those who contributed to this effort, and those who invented and made available the technology, belong to a common time. Rosenstock-Huessy was a man of his time, who reached back into times usually only of interest to historians and anthropologists, whilst thinking forward both to warn us of the dangers of our time, and to galvanize our faith in a time of greater concordance, one in which love, faith and hope converge so that we may better be able to achieve tensional bodies of solidarity—what he called a “metanomic society”—rather than persist in the cycles which lead us periodically back into hell.

Some of the people I have mentioned have now passed, others are still doing what they can to see his work take on a larger body of those who hear the urgency and respond to the perspicacity and grand sweep of his analysis of what being alive means, how it matters, and how lives over multiple generations have been formed.

Those of us who are party to this commemoration, irrespective of personality differences and styles of what we think may be the best tactic to gain a larger audience, irrespective of what we even think of each other, we are together because the trails and encounters of our individual lives have awoken in us a common appreciation of the “genius” of a man who has brought us together so that what we say, to each other and about each other, in his name, matters. Rosenstock-Huessy fought his entire life against the one-sided polarities which have divided philosophers into idealists and materialists, and thereby led them into metaphysical entrapments where pride in purporting to know the All subsists alongside a litany of errors which prevent us from knowing what really is important, what really matters, what really bears fruit.

It was Rosenstock-Huessy who most schooled me in the importance of our responses to the contingent circumstances that befall us, to the loves that move us, to the faith that focusses our observational powers about what matters in our lives, to the power of speech to bind or divide us, and to the times which flow around and through us, and how times are socially formed.

Each person here will know the major moments in the trails of their lives, even if not the countless trails of their ancestors whose offshoots they are, which led them to Rosenstock-Huessy. In my case, it was coming across Harold Berman’s Law and Revolution, while simply running my fingers across a library shelf in the library at the University of Adelaide, just as I had completed my PhD, which would become my first book, The Metaphysics of Science and Freedom: From Descartes to Kant to Hegel. Had I not been attending that university, had I not been at that section in the library, randomly walking by shelves, had the university not existed, Australia not been discovered, the printing press not invented, had that title not caught my attention (I had just taken up a job involving teaching a subject I had designed, called “Justice, Law, and the State”), had its position on the shelf rendered the book invisible, I may have never heard of Rosenstock-Huessy. And Harold Berman would never have written that book had he not been Rosenstock-Huessy’s student in Dartmouth. And my life would never have taken the trajectory it has had I not picked up that book, and you would not be reading this essay.

I may have remained caught up in the metaphysical grip of a way of thinking that has been as pernicious as it has been influential. I was certainly in the grip of that thinking when I encountered him. But I had already reached a stage where I was finding philosophy far closer to spiritual death than most ever realize. In my case, I can truthfully say philosophy was killing me when I encountered Rosenstock-Huessy. On that point, along with his friends Rudi Ehrenberg, Viktor von Weiszäcker, and Richard Koch, Rosenstock-Huessy always saw that the severance between nature and spirit was a life-threatening disease—and, for those who do not know it, and who have some German, I cannot recommend strongly enough his Introduction to the edition, with Richard Koch, of writings by Paracelsus—Theophrast von Hohenheim. Fünf Bücher über die unsichtbaren Krankheiten, whose subtitle in English reads, Five Books on Invisible Diseases, or Chapter 8, “Das Zeitenspektrum” (“The Time Spectrum”), from Heilkraft und Wahrheit (Healing Power and Truth).

When, thanks to Berman’s book, I picked up Out of Revolution, the opening sentences of Chapter One, “Our passions give life to the world. Our collective passions constitute the history of mankind,” struck me with such power that I was stunned. I suspect others in this audience may have experienced a similar feeling when they first read something by Rosenstock-Huessy, that feeling of being overwhelmed by an insight and how it is expressed, and feeling that this is someone who sees and knows important things. I know that not everybody responds this way to Rosenstock-Huessy. That is especially so with university people. I have had almost no success in sharing my enthusiasm and love of Rosenstock-Huessy.

Apart from my own failures to interest people in his work, the question of why he has not received a larger academic audience has to do with many things. First there is his style. His writing is sprawling and associative, connecting things specialists do not connect. His voice teeters on the conversational and it is laced with anecdotes drawn from every-day experience that do not resonate with an academic audience. His writing rarely, if ever, fits into a discipline—and hence, as he recounts in Out of Revolution, the university did not know where to put him, or what to do with him. His Sociology is many things, but it is most definitely not a traditional Sociology. He dismisses Weber and Pareto with barely a sentence each, but he connects himself with Henri de Saint-Simon, and proceeds to hail him as the founder of Sociology. He writes constantly about language, but he does not do Linguistics, and he almost only ever mentions linguists to rebuke them. Likewise, his writings on Christianity barely engage with theologians, and he finds theology as a discipline to be barren. That he disparages the importance of the mainstream (quasi-Platonist) understanding of the soul’s survival after death makes even his Christian faith look suspect to theologians.

The academic mind is inducted into an area of specialization, and that comes with being confronted with, and being required to participate in, various disciplinary debates and consensuses. He never agrees with any of them, whether it be the Q hypothesis in biblical studies, or the dual Homer of classicists. And he bypasses almost completely what Egyptologists have to say about ancient Egypt, with the odd expression of disapproval, relying for his interpretation of ancient Egypt on the basis of his own readings of Egyptian hieroglyphics. He frequently draws attention to the shortcomings of Philosophy. Where he does engage with philosophers, as in, say, his concluding chapter on Descartes and Nietzsche, in The Hegemony of Spaces, Volume One of In the Cross of Reality: Sociology, or with Descartes in Out of Revolution, he has such an original take that it also falls on deaf academic ears.

Then there is the overall vision. He has a providential reading of history, and the role played by wars and revolutions as the great powers of providence, at a time when providential history has almost no academic representatives. Even the Marxists have largely dropped the teleologism in Marx. But teleological history is not the same as providential history. The key point about his providentialism and how that differs from the progressivist academic orthodoxy of today is perhaps most easily understood if we distinguish between a cast of mind which looks to ideas and ideals, and attempts to rebuild society around the normative claims it makes. This is the standard way in which the philosophically influenced mind works—to be sure Marx transferred the site of development to the material plane, but, for all that supposed break with idealism, his position was still one of postulating what he already knew to be the best (ideal!) society (communism) and looking for how it would be realized. He missed two things that are intrinsic to Christian doctrine and to Rosenstock-Huessy.

First, reality is revealed, and not the result of thinking it through to its end. Secondly, our reality is inseparable from our sins. It is how we build with that that matters. The philosophers teach ethics. They do so because they believe that if we can act without error we will make ourselves and our world much better. This is idealism pure and simple. The difference between Christianity and philosophy and its predilection to instruct us in ethics and designing laws to make a better world stands in sharp relief to what Christianity is doing when we think about Peter and Paul, the two pillars of Christ’s Church. One was a weakling and a liar; the other a zealot and witness to murder. The Church is a creation of sinful flawed creatures. That is why Rosenstock-Huessy saw it as a miracle, and its very existence a confirmation that Jesus was the Son of God. It is the recognition of the salvation of the fallen, the forgiveness of sin, redemption through grace not the potency of our virtue and intelligence that is constantly at work in Rosenstock-Huessy’s writings. Thus too, Rosenstock-Huessy sees war and revolution as the greatest creative occasions not because they are good things, not because he is calling for a revolution in which we implement what we think will be the better future, but because they are symptoms and signs forcing us to recognize the dead ends we have reached: they are spiritual diseases. They reveal us at the end of our tether, and are the preconditions of our ways of dying into a new form of life. One of the inner secrets Rosenstock-Huessy sees in Christianity is that it teaches how we must die into new life.

Rosenstock-Huessy also makes Christianity the root of the tree of universal history, in a century where the academic mind has largely been devoting itself to a neo-pagan revival, as most evident in the importance of what Rosenstock-Huessy calls the four dysangelists of Marx, Darwin, Nietzsche and Freud, each of whom is involved in destroying the traditional components of every civilization, including Christian civilization. While Rosenstock-Huessy goes deep into why the various pillars of civilization exist and why their modern destroyers are so destructive, he is as little interested in defending tradition for the sake of tradition, as in congratulating those who think that we have simply outgrown traditions because we are smarter and better. But he is interested in the collected learning of the species, of the creative, revelatory and redemptive aspects of life which accompany how we organize our lives, how we orientate ourselves as we command and call, declare, and refuse, and then occupy the different fronts of reality that our lips and hearts and hands have opened up.

We all occupy different positions in the various fronts we encounter through our various social allocations, from the family to the division of labour, to our culture, and so forth. A tradition is only a tradition in so far as it is a living pathway of spirits; pathways can run out of spirit; they can be merely dead ends. The tension between anchorage and dwelling, and the spirit’s movement and growth is one of the most important of the species. Societies can be equally doomed by a refusal to grow spiritually, by idolizing their traditions, and by becoming unhinged as the enticements of our desires and imaginings sever us from sacrificial requirements intrinsic to love’s existence and movement.

Rosenstock-Huessy takes cognizance of the fact that all life is about mutation and transformation (which is why he identifies with the Christian fathers who saw Heraclitus as a Christian before Christ’s birth). The power of the language of religion, he would say in Practical Knowledge of the Soul, lies in it, addressing the secrets of transformation. We can never be alert to mutation and transformation if we neglect the importance of contingent encounters, or the creative opportunity that a moment may call for. The meaning of our actions are only revealed through our responses to the circumstance of the moment—not by our plans and intentions. Thus Rosenstock-Huessy emphasises that responsiveness is a condition we ever find ourselves in—not “cogito ergo sum,” as he famously said, but “respondeo etsi mutabor.”

Knowing when to preserve and when to jettison, how to respond to the requirements of the time and circumstance, how to know whether the powers of the tradition are alive or dead, having a sense for which of the hidden powers of the future are to be fought for and given over to, that is part of the cross of our suffering, the trial of our lives, the test of our faith. This is something that is simultaneously something that we are never sufficiently prepared for but what we most need to be educated for. This is also why Rosenstock-Huessy, in the first volume of his In the Cross of Reality, places such importance on how games or play prefigure in our lives—they are means for preparing us for the serious and the unpredictable contingencies which require on our part an astuteness of observation and a strength of character. Neither of these qualities are particularly highly valued by a modern education system which prioritises principles ostensibly encompassing the sources of all our greatest social problems and their application which will ostensibly solve them. The sporting field, though, is a preparation for the battlefield, and the “battlefield” or “theatre of war” is the most serious space in which life is tested.

Rosenstock-Huessy’s view of life owed much to his experience on the battlefield. His conceived War and Revolution amidst the horror of Verdun. The sense of urgency, of trauma, of the horrors we are capable of unleashing, and of what is required for our survival, as well as what contributed to the nations of Europe killing each other on such a scale are woven everywhere into his writing. They give his voice a sense of reality that comes from being covered in mud and splashed with blood, from watching his comrades killed in combat. It is a voice that does not simply come from the study, which I suspect is why those who live in and from the study and the classroom rarely respond to it. That is also why how he approaches the great task of building a lasting peace has nothing in common with the far more popular figures such as Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Jacques Derrida, Jacob Taubes (who for a year corresponded with Rosenstock-Huessy), Giorgo Agamben, Slavoj Žižek and Alain Badiou, all of whom sought to implicate the modern radical project of emancipation within the theo-political one of the messianic. And they, like their less theologically sensitive contemporaries, such as Gilles Deleuze, and Michel Foucault, who have had such an important influence on the ideas circulating in the Arts and Humanities, all view traditions and social roles as if they were explicable through the dyad of oppressor and oppressed, and hence as if what mattered most in a life was that it could be lived according to one’s desires.

But they also want to expose the shaping of desires by the dominant social powers and the ideologies that sustain their privilege, as that very shaping of desires also is a symptom of oppression. Emancipation thus always comes back to appetites, and sociality magically forming some chemical compound to be released in utopia or the “to come.”

However philosophically clever and satisfying the above thinkers are to students and professors who think that ideas exposing who has more, and how much more “power” we will have when emancipated, Rosenstock-Huessy had no time for such vapid analyses that betray the idealistic vapours of their conjuration. Thus he rarely mentions any of the major figures of twentieth century Marxism in his major writings. In some letters, we discover that he thought the revival of 1848 in the age of world wars was a disgraceful failure to read the times. He also lets off steam about Habermas, Adorno and Bloch, while he seems oblivious to the French structuralists and post-structuralists who had started to make a name for themselves in the 1960s and who would go onto play such a large part in the kinds of political narratives coming out of universities in the last forty or so years.

In sum, what the generation who came of age as they were being educated in the 1960s came to see as the great voices of orientation, the very voices which came to play an ever bigger part not only in university curricula, but in policy, were either unnoticed or dismissed by Rosenstock-Huessy. The idea that the greatest problem confronting the species was to overthrow the forces of oppression to emancipate the self we—and those who think just like us—identity with was completely alien to Rosenstock-Huessy. And it is the lack of such a core principle in his work that also continues to alienate him from readers who are of, or trained by the academy.

Whereas the academy has come to play a major role in the narratives which have now come to define the West, neatly now summed up as policy formulations of Diversity, Equity and Inclusivity, Rosenstock-Huessy saw freedom as both a decisive feature of what we are and of the better, more Christ-like, world. It is inseparable from the Holy Spirit, and his take on freedom is yet again an indication of how he diverges from the commonplace distinctions of philosophy which are now so engrained in the mind of the educated public, and the way his faith informs his eyes and ears and throat and heart.

Please indulge me the following excursus into the history of modern philosophy. For if we understand the underlying connections between the modern elevation of the value of freedom, the specific meaning that freedom takes on in the modern context (one very different even from classical philosophy), and the underlying metaphysical parameters within which it emerged, we are in a far better position to appreciate how we are still very much entrapped in the mental prison that Rosenstock-Huessy was trying to break open. We will also better appreciate why Rosenstock-Huessy’s Christian solution is a genuine solution to what commenced as a dream (Descartes’ dream) and has become a living nightmare.

The modern philosophical view of freedom emerges in the broader metaphysical dualism of determinism and voluntarism. They are the polarities which Descartes appealed to in his claim that there were two fundamental substances which provide the basis for all of our understanding of reality—one is immaterial (the mind), the other is defined by virtue of it being extended (the body). Mind, though, in Descartes solely consists of cognitive operations, so the voluntarism in Descartes is strictly limited to acceptance or negation, while the body is construed entirely deterministically. While the particular means identified by Descartes as required to explain causation was abandoned thanks to Newton’s demonstration of the fact (not hypothesis as he proudly declared) of action at a distance, the far more important philosophical contribution made by Descartes was the metaphysical redefining of the world as a totality of laws operating through causal mechanisms, i.e. determinism.

The German idealists (though not Hegel), but especially Kant, the young Schelling, and J.G. Fichte developed the voluntarist metaphysics that is so widely embraced today. In Kant that voluntarism was purely limited to our moral claims, but it finds it most complete form in J.G. Fichte, the major philosophical figure in the Romantic and nationalist movements in Germany, who is barely read today. Fichte had taken the Kantian and Rousseauian idea of freedom being submission to a law which we give to ourselves and extends it to any and every activity where there is human involvement. Thus life itself as we fathom it and participate in it through our consciousness of it and ourselves, for Fichte, is but the self-conscious postulation of the ego. Hence the world is but a fact-act, and our relations are all potentially contractually formed, albeit on the basis of some intrusions by the non-I, which are, inter-alia, racially determined (hence his nonsense on the German character.)

The highpoint of Fichte’s fame was in 1806, when he delivered his Addresses to the German Nation, which was a call for the unification of the German people into one nation to counter the Napoleonic conquests. By the 1830s his fame had dropped away, but his influence had impacted indirectly upon the romantic radicalism of the young or neo-Hegelians. In spite of their name, the young/neo-Hegelians were generally radically anti-tradition and anti-institutionalist and in this respect deeply opposed to Hegel’s philosophy of the reconciliation of the Enlightenment spirit of diremption. They are mainly remembered today because its “members” included Karl Marx. The most philosophical amongst them was probably Ludwig Feuerbach whose critique of Hegel was to be repeated by the young Marx. The two figures in that group that are most conspicuously Fichtean in their philosophical formulations were August Cieszkowski, and, Max Stirner. Cieszkowski is all but completely forgotten, but while Stirner’s work of anarcho-individualism, The Ego and Its Own was philosophically light-weight compared to Fichte, his name has survived, in part due to the merciless polemic against him by Marx and Engels in The German Ideology, but also because he would be an important influence on Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche, though, was also deeply influenced by Schopenhauer, whose polemics against Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel contain some of the best comic lines in the history of philosophy.

Schopenhauer’s philosophy also proceeds by way of metaphysically uniting determinism and voluntarism. He does this by making the will the underlying creative material power of the universe, which is also inseparable from the representations that accompany its incessant drive. He had, so he claimed, bridged materialism and idealism by uncovering the nature of Kant’s notoriously elusive thing-in-itself—Kant had claimed “the-thing-in-itself” was a necessary postulate of reason, that we could never understand, because it lay beyond the mental strictures of our “experience”—it lay outside the parameters—the a priori elements of what he called the faculty of understanding. Nietzsche would simply appropriate this hybrid of material determinism and the will as the fundamental power of the universe.

But whereas Schopenhauer’s response to this was to seek retreat by withdrawing his mind from the world and the restless tumultuous will that was the source of all our suffering, Nietzsche merged a physiological/ biological (determinist) view of human beings with the more Fichtean and Stirner one of heroic potency. Nietzsche ridiculed “the heroic,” a term being bandied about by Carlyle (also an admirer of Fichte), but his superman is a call for the breeding of just the type Fichte had made the high point of his philosophy.

The same deterministic-voluntarist hybrid, albeit without the philosophical self-consciousness and deliberation of Fichte or Schopenhauer, is also in Marx. He claimed to have demonstrated the necessity of socialism arising from the break-down of the bourgeois mode of production, whose laws he had claimed to identify in Capital. But the movement between bourgeois and socialist society was also predicated upon the revolutionary act by the industrial working class, i.e. that act and class were the sine qua non of socialism. In spite of his constant refrain that consciousness was determined by society and not the other way, Marx himself laid out a theory of ideology which would be essential to the radical thinking of the next century. For without clearing away the ideological distortions which protected the ruling class that action might not occur. The proletariat, in other words, needed to be educated, needed to have their consciousness raised. His theory contained two irreconcilable “absolutes”—one (the reality of the capitalist mode of production) studied by the scientist , the other (a non-existent future socialist and then communist society) appealed to by the revolutionary. Eventually the revolutionary Marx quietly adopted the kind of voluntarism that would define Leninism: that moment came when Russian Marxists asked Marx if they could bypass capitalism taking hold in Russia and leap straight to a socialist society. He replied, Yes—and with that he tactility renounced the deterministic basis of his own theory: consciousness could in fact determine social being.

The one philosopher who grasped the importance of the metaphysical bifurcation that had been playing itself out since Descartes was Hegel. He had argued that the modern metaphysical bifurcation of determinism and voluntarism was but one more unfortunate legacy of the Enlightenment’s division of the world into the finite, and infinite, which, he argued, rests upon a dogmatic (and philosophically false) belief that the finite is not a moment within the infinite, but a separate part of it. That is, it cuts us off from the world that it purports to exhaustively define so that we can understand all its laws. Hegel was correct to see the dialectical relationship between determinism and voluntarism. His mistake was his faith in philosophy itself—and even how he pits faith against philosophy involves the error that explodes his entire edifice. That error is most visible in the key to his entire corpus, his lesser known book, Faith and Knowledge. While it provides a brilliant analysis of the philosophies of Kant, Jacobi, and Fichte, it is based upon a completely false understanding of faith.

Although Hegel admired Hamann, and wrote a very positive and lengthy appraisal of him, had he read him more closely he would have realized that faith is not something arrived at when knowledge reaches its end. The idea that faith was required when knowledge reached its end was what the Romantics had in common with Kant, and it was this that Hegel kept finding and criticising not only in Kant, Fichte, and Jacobi, but young Schelling, Schleiermacher, Fries and other contemporaries. His point was like Kant, who had denied any knowledge of the thing-in-itself, only to tell us a lot about it, they all speak of the limits of knowledge only to tell us what they know lies beyond knowledge, and how we too might know it! While Hegel’s argument against the philosophers and theologians is compelling, it, nevertheless, misses the point—that faith is what leads to knowledge and indeed to the life you have, not what takes place outside or beyond it. It is utterly existential, and world-making.

When one sees the ruin of Hegel’s life-time work, a system with nothing but rubble to be picked up by subsequent generations we cannot help see (I at least) the deep failure that incubates within philosophy. For none has done a better job than Hegel in demonstrating that any subject we consider is only what it is because of its predications. The more knowledge we bring to/have about the subject, the more we see what it is. That is a very clever defence of science and the importance of knowledge as a systemic enterprise—but it overstates the importance of reason and ideas and underestimates the things that Rosenstock-Huessy emphasises which are required in knowledge and which I talk about at the end of this paper. Thus it is, for Hegel, that to know the part requires knowing the All that informs the part. That is a brilliant metaphysical insight, and it sends Hegel on the path of writing The Science of Logic and The Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Science, and the most magisterial account of the history of philosophy ever given, as it demonstrates how his philosophy is the culmination that recognizes the conceptual development and labour that led to him.

If philosophy from its origin aspired to the God’s eye view, it is Hegel who has the eye of God. Or so it would be the case if he were correct, though we can see how silly it is when we start to look at some of the errors of judgment he displays in his Philosophy of Nature, especially. But our life is not formed in the study, nor by denoting the dynamic of our contradictions. It is formed by the faith that has carried us to where we are as it also moves us to our next action. This by the way was why the deeply religious Hamann liked Hume so much and forgave him for his more enlightened nonsense. Hume understood that faith is a motivation where all our knowing can be sceptically broken down if we pose the right questions to it.

Hegel, aside, the disjuncture between determinism and voluntarism remains very much with us in our confused world. Here Hegel’s genius retains its relevance. For we can see that because the greatest faith in the Western world today is faith in their ideas about the world and they themselves are caught up in the constant oscillation transpiring between the polarities of the metaphysical spectrum upon which their ideas “pop up.” More often than not the oscillation (Hegel’s dialectic of contradiction) transpires within the one narrative. An extremely common one involves being drawn into identifying the determinations of identity (gender, race, ethnicity etc.), whilst at the same time rallying behind the (wilful, i.e. idealist driven actions) overcoming of those determinations by changing our ideology.

The contemporary soul, in sum, in so far as the modern project is to a very large part a philosophical—an ideational—creation is torn between two absolutes, the absolute of the universe and the social forces that are treated as naturalistic variations of ideological social power, and the absolute of emancipation in which the rights of the oppressed subject triumph over the unjust imposition of the privileged. But the concept of emancipation is also implicated in the other metaphysical oscillation concerning freedom which accompanies the determinism/ voluntarism dyad, which was at the centre of Kant’s (unsuccessful) attempt to provide an unassailable metaphysics. That was the division between freedom as the formulation of a categorical imperative (i.e. the capacity to make unconditional universal moral commands) and simply giving into the appetites (our appetites, in this schema, are simply bodily determinations). From the Kantian perspective surrendering to our appetites is the antithesis of freedom—so much so that he holds that no act is free if is affected even by the tiniest degree by an appetite.

Kant aside, the idea of freedom has become extremely commonplace today, although the idea of our freedom requiring removing the strictures upon the appetites is the view of freedom to be found at its most brutally honest form in Sade, and in a more humorous version in Rabelais’ less semen and blood-stained depiction of the kind of giants we could be were we free of religious superstition, priests, bad rulers, lawyers, scholastics, etc.

The liberal view of freedom, which goes back to Locke and takes persons and their property as the bastions of liberty, mediates between the appetites unbound, and the binding required of other appetitive beings. That human nature is nothing but appetites in motion is also an offshoot of the deterministic metaphysics of the modern and is laid out by Spinoza and Hobbes, and it will be this view of the self without freedom or faith in its own dignity that will be a major impetus for Kant’s critical philosophy.

The politics of emancipation in the West (and they have no real resonance outside of the West today), though drawing upon “moral” posits which give it normative leverage (the leverage of shame), is the dialectical resolution of the modern components of the idea of freedom. It incorporates the satiation of one’s appetites, the right of respect (dignity) for having one’s appetites and determinations (being/ identity), control of education to enable the breaking up of oppressive/ traditional forms of social reproduction to enable this dignified/ appetitive self, as well as the political demand that this emancipated self receives the resources, whether through reparations, or career and office holding opportunities distributed on the basis of one’s being/identity, that enable its perpetuity. Indeed as we are witnessing, the emancipated self requires for its realization a complete overhaul of the entire political, economic, pedagogical and social spheres. That it has generated an all-encompassing alliance between the state, corporations and those who determine which ideas are to be taught and publicly tolerated in order to sustain this new world of new selves also requires an unprecedented technocratic, bureaucratic and ideocratic alliance.

All of this is as remote from Rosenstock-Huessy as pretty well any other kind of campus-initiated politics that have grown out of the student revolution and its aftermath. In sum, then, for Rosenstock-Huessy the secret of freedom is not disclosed by Descartes, Spinoza, Roussea, Kant, nor Fichte nor Sade, a decisive influence in the French pot-pourri of Bataille, Blanchot, de Beauvoir, Sartre, Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze and Guattari, who have played such a huge role in the Arts and Humanities in the Western world, nor Marx nor Nietzsche. even if Rosenstock-Huessy finds things in Marx and Nietzsche which he sees as valuable. It is to be found in the partitioning of time, and the foundation of a new time. For Rosenstock-Huessy the great partitioning occurred with Jesus, for it would both bring an end to all of what he called “the listening-posts” of antiquity, that is the distinct life-ways of tribes, empires, city-states, and the diasporic Jews bound by their God, their belief in His promise, their prophesies and expectation of a Messiah, as well as breathing new life into them by raising them to another socio-historical plane and purpose.

Rosenstock-Huessy’s argument about where Christianity fits into the larger scheme of a universal history can be seen as a variant of the kind of accounts we find in the writing of people like Frédéric Ozanam, Christopher Dawson, and G.K. Chesterton, though I think once the second (and third, depending upon the edition) volume(s) of his Sociology are factored in with the two studies (the German and English versions being organized differently and having somewhat different emphases) of the European revolutions then his account is sui generis. Like any historical account, and especially when it covers such a massive array of events, some of its findings as well as the stations on its way are disputable.

However, that he provides an account of history in which he draws attention to so many variables being of consequence for the world we now live in, and that he does so balancing structural (especially in the Sociology—though, it would also be the structural features of his study of the European revolutions that would lead to a preface to the Die europäischen Revolutionen being written by the doyen of structuralist/systems theory Political Science, Karl Deutsch) and contingent features lays out a great research project that remains largely neglected. Although Berman’s two volumes of Law and Revolution is an important contribution to the development of that project.

But just as the Christian centre of his universal history has left his work being neglected, the method is also something that leaves the work being neglected. That he has a method is something he makes clear in the first volume of his most methodical writing, the first volume of In the Cross of Reality/Sociology. But just as his understanding of freedom has nothing in common with the philosophical way in which freedom has developed, his method is what he calls the cruciform one in which there are no such things as objects per se or subjects per se, even if we are to retain that philosophical language, which Rosenstock-Huessy only very occasionally does, nor are future and past unmediated by each other.

We all find ourselves torn by what we each bring to a situation, as well as what has gone into creating the situation which takes us far beyond what can be encapsulated in the words of subjectivity of objectivity. Words like subject and object have such philosophical importance because of the philosophical willingness to eliminate the complexities which overly complicate the process of having clear and distinct ideas. The terms are the result of a decision to simplify reality so it is better controllable. The terms subject and object conceal an array of actions, circumstances, occasions, historic and semiotic backdrop and inherited lexicon and knowledge-pool, as well as the associations and memories that we have and do not even know we have until we speak. “Speech,” and Rosenstock-Huessy folds writing into Sprache/speech—discloses us to ourselves as much as it communes with others—and these in turn are enmeshed in what he calls our prejects, what calls us and pulls us from the future, and trajects, which push us.

At the most critical moments we are literally torn apart between competing directions, in and at the cross and the cross roads. This is also why Rosenstock-Huessy also deviates so decisively from the general tenor of the modern mind which thinks that through its intentions and designs it will get the world it wills, as if the self and world are not inexhaustible mysteries which are revealed by the word and over time through our participation in life, but substances to be analysed into clear and distinct ideas and synthesised so that we can be masters of ourselves and the world. In sum, the modern philosophical position which has seeped so deeply into the world is one which exists in defiance of the Holy Spirit through its elevation of the self as subject, or, which is in essence no different, the elevation of our understanding of “the All” whose most important determinations have been identified by our great luminaries.

Rosenstock-Huessy is a counter-Enlightenment thinker, in the vein of Hamann, in so far as he prefers to throw himself on the ground and pray in the midst of that cross-road because he knows how fragile we and our minds are. He would rather trust the Holy Spirit than the technocratic spirits which have emerged out of the modern philosophical imagination and its limited but insufferably proud understanding. His writings are testimony to that Spirit. What I recounted earlier about the way I came to Rosenstock-Huessy, and what have suggested about the way everybody has come to him is exactly the kind of meaningful event in a life that Rosenstock-Huessy has taught me to appreciate the living presence of Holy Spirit. But thinking thus, and seeing the world thus necessarily puts him at odd with the entire academic mind-set of today which, at its worst, see the world and our participation in it through a technocratic/and or ideological template, and, at best, through the systemicity we may gather through positioning ourselves within the sciences, including the human sciences.

The Holy Spirit though is not a thing, and certainly not anything that can be adequately incorporated into a social or human science, at least so long as the sciences proceed according to the strictures that were designed to study nature in its mute “object” manner. But that approach to nature also involves us blinding ourselves to ourselves. On that front it is most interesting to compare Rosenstock-Huessy’s comparison, in Der Atem des Geistes, of the respective insights and ways and means of Michael Faraday with those of Eddington. Rosenstock-Huessy rightly indicates, no science of anything would be possible were it not for the breath of inspiration of a founder of a hitherto unknown pathway of the spirit, and the inspiration (the shared breath) that the founder is able to instil in others who follow down that path as they take us further into unexplored aspects of life. Nietzsche had claimed that the ascetic ideal in Christianity prioritised truth in such a way that it opened up a pathway for science, but Rosenstock-Huessy takes seriously what most philosophers simply ignore and that is the personal dimension and interaction of those involved in research, and the spirit that binds them in their inquiry. Thus he addresses not only what knowledge is for, but for whom it is for.

I will return to this toward the conclusion of this essay but here I wish to emphasize Rosenstock-Huessy’s recognition of the primacy of the elemental component of a living process is what is invariably left behind in abstraction. As I have hinted already what Rosenstock-Huessy teaches about Christianity, and what he finds in Christianity is what has mainly been lost, especially by theologians, about why it is important: what it reveals about life.

We live in an age where doctrine and abstraction proceed as Siamese twins, where it assumes that a doctrine such as is embodied in the Christian teaching came out of someone’s head, rather than out of lives lived, and it is what was picked up and then taught by the lives lived in devotion to a particular person, a person acknowledged and revered by those who witnessed him as a person who was both man and God, someone from whom their lives took on such a meaning that they saw themselves as being reborn through their faith in him. Rosenstock-Huessy had said that his faith was something he grew into because could never understand “why everybody did not believe the Nicean Creed.” Those are not the words of someone who thinks abstractly, but rather someone who has an uncanny perspicacity, the ability to see the relationship between the spirit and flesh of Christendom and the words that those believers at Nicaea formed with such precision and purposefulness. What Rosenstock-Huessy sees as exemplified in Christianity is the illustration of the word becoming flesh: life, teaching and actions belong together, as he writes in his masterful essay, “ICHTHYS”: they are a trinity, and as such they are the cure against what Rosenstock-Huessy identifies as “the three infernal princes—of the senses, of thought, and of compelling authority.”

But it is precisely because in forming a world where ideas matter so much we have not become better attenuated to life and its commands and demands but we have deafened and dumbed and blinded ourselves as we deal in words that lack life. We misuse and abuse names that once had power, and now they reflect back our own emptiness and powerlessness, our preference for the dead and the mechanical over the real that is love’s creation. We simply cannot fathom the experiences that gave rise to the names that created the Christian world—the experiences have become completely invisible to us because the words are but husks.

Rosenstock-Huessy’s most systematic work was his Sociology: In the Cross of Reality, which was divided into a critique of the hegemony that spatial thinking had come to play in the world, culminating in the suffocating tyranny of its imposition that had been ensconced philosophically, and an account of the times that have made us into planetary neighbours. While he often had praise for Nietzsche, he saw that the arc of modern philosophy from Descartes to Nietzsche was a fateful one for modern people. For we have become swept up in a technocratic view of life (going back to Descartes) in which the world and we ourselves are but components or resources to be dissolved into an infinitude of space, measured and reincorporated and reconfigured to conform to the plans and machinations that are supposed to emancipate us. Much of The Hegemony of Spaces is devoted to the importance of roles and the way in which they socially position us for our cooperation in making our way in the spaces we operate within. The philosophical prioritising of spaces in an age where philosophism has undermined and in many way supplanted the ways and the role of the Church also comes with the target of eliminating roles so that people better pursue their individual happiness. The rationale of roles within the family, the workplace, the school, which provides our named placement in the social order, which induct us, and steers us through the processes where we must learn the difference between shameful acts and the responsibilities which come with our role, is bound up with the fruits that we all must socially harvest if we are to have concordance and growth. Once again Rosenstock-Huessy sees the reductive and destructive force of the materialism/ idealism truncations and their naturalistic/ scientistic counterpart cutting away at how we are able to access and creatively participate in the spiritual development of the species. The grave threat facing “modern man,” requiring that he “outrun” it, is sterility, a sterility of spirit that also shows itself in its suicidal self-destruction, in its concentration camps, in its danger of turning the life-world into a gigantic factory.

If the motherless Descartes was the mother of this world, the fatherless Nietzsche aspired to be the true father who would give birth to the superman who would rule the earth. For Nietzsche the modern world is the barren offspring of the “marriage” of scientism (Descartes) and aestheticism (Nietzsche). Both swallow up the complexity of real life with their abstract fantasies. Nietzsche holds out the promise of meaning that has been shorn off our lives as but mechanical parts of the universe by Descartes. It is a deluded promise made by a man who saw much but missed much, most notably the sterility which becomes satiated by imagined children being a substitute for real children.

The second volume of Rosenstock-Huessy’s great masterpiece was devoted to one overarching theme, an account of the great times that have contributed to a universal history. The infinitization of space has as its corollary the infinitization of time, which is another way of saying the reduction of all the social creativity that has formed different times, different epochs, different generations, different ages of the spirit. Rosenstock-Huessy’s contribution to countering the spiritual and existential mass murder of reducing us and our lives, our traditions and achievements, our future hopes, and our faith and loves to spatial confinements and mechanisms is to draw us into what he calls the Full-Count of the Times.

The work as anyone knows who has read it brims with brilliance: it betrays the kind of erudition that is the preserve of the most learned of his especially learned generation; it teems with brilliant aperçus, and it makes the most marvellous connections across periods that convey an entire sense of meaning and spiritual purpose to great periods of time. Of course, it is a specialist’s nightmare. But, apart from the dire need it has of an editor who may have salvaged some of the syntactical leaps which drag entire paragraphs into thin air without leaving any trace of meaning behind, it is a work which consciously seeks to connect the lost and forgetful man of the mid-twentieth century with the multiform conditions of which he is the sociological, historical and spiritual heir.

Although he is, as I have repeated throughout a Christian, he explains in numerous works why being a Christian is not simply defining one-self against other religions and gods, but is to enter into a tradition which is founded upon the incorporation and reinvigoration of the living beyond death that precedes it. For Rosenstock-Huessy being a Christian means being open to God’s creation, voice and promise, and one cannot do that if one comes with a theologian’s or philosopher’s truncated and distorted understanding of God. A god is a living name on the lips of people—a people’s existence is bound up with the spirits they serve, the voices they respond to, what they hold sacred, the commands of their god. Rosenstock-Huessy often made the point that people first needed to understand the gods before they could begin to understand what they were talking about if God’s name arose.

And talking about God was already a sign that one was missing the point. The living God is meaningful only in relationship, in communion, in prayer and obeisance and supplication. But in so far as one is trying to explain the spiritually living to the spiritually dead, one has to imaginatively enter into life worlds remote from our own, life worlds we might never have thought about, but without which we simply would not be what we are. Few, apart from Herder, have laboured as much as Rosenstock-Huessy to explore the historical, sociological and broader cultural conditions which are part of the human story. It is the fact that, for all our differences, we are part of one family. This is why the Aborigine is the kin of the modern office worker, though on the surface they may as well live on different planets. How have we come to inhabit such different worlds, with our different traditions, our different ways of world-making, our different orientations and priorities, our different “gods” and values, hopes and expectations?

But no less important is the question, how is it that in spite of these differences we not only live on one planet, but we find ourselves conscious of the fact that there are so many different worlds, different calendars, different cultures etc. and that we also can speak to and of each other? These questions are burning ones still and Rosenstock-Huessy’s project (here he is very much following the pathway of Herder) is one which requires we drop the philosophical nonsense and norms of Western imposition and listen to each Other. Yet one more irony is that it is precisely those who do the philosophical imposition, who see the world through its norms, who are most hostile to the universal message of Christianity, and its response to the universal condition of human suffering.

Rosenstock-Huessy had an uncanny knack for tapping into that suffering and for entering into the different life worlds, as he looked to the powers and spirits that animated them, the circumstances which exhilarated and terrified them, and the creations and prayers that distinguish them. In antiquity he identified four distinct life-worlds: the tribe, the empire, the Jewish diaspora and the Greek city state. For Rosenstock-Huessy if we fail to understand the spirits of these groups and their legacies we can never appreciate Christianity. If we fail to see the power behind animism, and the powers that connected human beings with their ancestral animal teachers and tribal ancestors, if we fail to appreciate how polytheistic societies arose and what they generated, and what crises befell them, if we cannot appreciate what the Jews learnt from their enslavement and exile, why they awaited a messiah, how will we be able to appreciate the miracles that may spare us from the hellish darknesses that have always befallen civilizations, and peoples?

Rosenstock-Huessy lived through the world war(s) (he believed, rightly in my view, they were but the one event) and fought in one of its phases. But what he saw was that in spite of the horror and darkness, there was survival, and he very much saw that capacity for survival as coming out of the spiritual reserves provided by the Christian faith. The importance of Christianity lies in large part in the spiritual reserves that it has absorbed from peoples and practices who knew nothing of it. We are, for Rosenstock-Huessy, bonded by the realities that different faiths and orientations have discovered and generated and which are part of us and our world, in spite of what we might want to think or believe. Thus he writes in The Secret of the University (Ray Huessy provides this quote in his marvellous introduction to his new edition of The Fruit of Our Lips): “We must all create originally (like the pagans), hope in expectation (like the Jews), and love decisively (like Christians)— that is to say, we must take part in the beginning, end, and middle of life.”

What Rosenstock-Huessy expresses here as an existential truth, an observation about ends and beginnings and the middle of history, is preceded by the life of Jesus, whom he accepts and follows as the Son of God, the genuine middle, “the hinge-point” of history, the moment where the ages are cleft into BC and AD by a life that shakes up the worlds that preceded it and sets them on a new path. In The Fruit of Our Lips, Rosenstock-Huessy talks about the spiritual dead ends that had been reached that provide the opening, the need for Jesus to be the answer to the human prayers:

Jesus was in fact the end of our first world. He took the sins of this first world upon himself. This sentence simply recognizes the fact that in separation, tribal ritual, the temple of the sky-world, poetry in praise of nature, and the messianic psalms, were all dead ends, {in the immutability of their one-sided tendency}. In this sense Jesus’ death sentence was the price of his being the heir of these fatal dead-ends. They slew him because he held all their wealth and riches in his hand, heart, mind, and soul. He was too rich not to share in the catastrophe of the all-too-rich ancient world. {So it was his duty to be the one condemned by the king, the one sacrificed by the priest, the poem of the poet, and the one foretold by the prophet} (41),

It is interesting to note in passing how the more philosophical minded trying to fathom our historical condition can, as Agamben, Badiou, Taubes and Žižek have done, take Paul seriously, but not Jesus (Žižek, the most clownish of these characters at least provides a clownish account of Jesus as a monster who fits into his Marxian-Hegelian-Lacanian schematic overriding of history and spirit). That they take the teacher more importantly than the one whose life gives meaning and purpose to the teaching conforms to the type that Rosenstock-Huessy saw as so unfit to teach because their priorities do not conform to how life and the spirt of life works. What we teach is only actual when it is lived first.

The gospels are not a compilation of doctrines but the record of a life that bears fruits that must be taught and carried into actions. And the life that was lived was what it was in large part because of when it was lived. The who and the circumstance and the encounter are all part of the spirit of the truth and its power. The realization of the power of the life of Jesus required respondents who would take his life and take his teachings into the world so that new pathways of life, new lives could be formed. Jesus’s life was the seed to be spread while, says Rosenstock-Huessy, “The four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are the lips of the risen Christ. These lips bore fruit because Jesus was also an answer to their prayers. The four Evangelists lay down their human limitations at the foot of the cross and transform their individual experience into a contribution to the community.” What the modern secular minded person can easily dismiss as merely the stories told by believers and fanatics, in Rosenstock-Huessy’s eyes reveals something astonishing—and the problem with the smug dismissal lies in the complete disjuncture between cause and effect. The irony is all too conspicuous in so far as the great principle of continuity in Greek thinking is the dogma of the equivalence in power between cause and effect. And yet we see the refusal to acknowledge this very principle by those who otherwise invoke it all the time.

For the Christian something great can indeed come from something tiny, the character of a thousand years can be born from the flame of faith in hearts awed by the words and deeds done by the right person in the right time. Faith and miracles go together, and they are intrinsic to Christianity, beginning with the miracle of the world’s creation, and the story of the fall that comes from a lack of faith/trust/ obedience in God’s promise.

How faith is formed owes much to who has the faith and what it is in. Jesus lived but it mattered who responded to him, and who responded to them. That he had the respondents who had their faith is also, from this point of view, this faith-held view, and that they reported their accounts of the life of Jesus and what he taught in the order they did is yet another miracle, or what Rosenstock-Huessy more prosaically refers to as “remarkable.”

“There is” observes Rosenstock-Huessy” a remarkable sequence in the authors of the four gospels”:

Jesus’ name in the old church had four parts: Jesus, Christ, Son of God, Savior. The four Greek initials of these four names were read as Ichthys (fish). The four gospels proclaim this name. Matthew the sinner knew that the Lord was his personal savior (= Soter); Mark knew him from the beginning as the Son of God (Hyious Theou); Luke saw Christ who had converted Saul, to whom Jesus had never spoken (for Paul, Jesus could be nothing else but exclusively Christ); John, the kindred spirit, knew him as an elder brother, that is, he thought of him as “Jesus,” personally.

In spite of Rosestock-Huessy drawing upon biblical scholars and traditions to make his case, one thing that I have not seen anyone else address with such startling insight is his claim about the way in which the gospels form a unity through their positioning on different fronts to different communities. And it is this approach that I see as providing an invaluable example of how our history should be told. It takes the most important, the most world-shaping, book in the world and demonstrates how it is a living example of the circulation of spirit, how truth is polyphonic, how it is nothing without the bond between speaker and listener, how the specific speaker and the specific person/community being addressed matter—and concomitantly how any idealistic reduction, i.e., dissolution of the living encounter and the teaching expressed in that account dies if it is diced up and regurgitated as mere ideas. Allow me to quote two passages from The Fruit of Our Lips, the one tells us something important about the speaker/ writer, the other about the listening community:

1. John writes as an eye-witness who knows the minutest details when he cares to mention them. The apostle is the author of the gospel, and that is why it carries authority.

2. All four gospels are apostolic. Matthew was the converted publican {among the apostles}, and he wrote under the eyes of {Peter and the sons of Zebedee and} Jesus’ brother in Jerusalem before the year 42. Mark obeyed Peter. Luke lived with Paul. John dictated to a Greek secretary.

3. Matthew wrote in Hebrew, not in Aramaic, and he was the first to write.

4. Mark states bluntly that he is quoting Matthew (47).

and:

John spoke to people who knew the arts and sciences; Luke spoke to the greatest high churchmen and Puritans of antiquity; Mark spoke to the civilized inhabitants of the temple states. But thanks to his “bad taste,” Matthew penetrated to the most archaic layer of all society, to the tribal layer of ritual, and so Matthew gave us a version of the gospel that was to become the most universal and fundamental characteristic of the new way of life. The Mass and the Eucharist, the inner core of all worship, is identified in Matthew [26:26–29]. Since he made clear that by His sacrifice Christ had purchased the salvation of the sacrificers, the scripture now says: At every meal, the sacrifice that is the bread and wine speaks to the dining community and invites us to join our Master on the other side, so to speak—on the side of the victim (92-93).

Finally on the importance of Christianity as “the hinge point of history”—and I should emphasise that it these few citations do not remotely compare to the detailed case Rosenstock-Huessy makes in the Full Count of the Times—what matters as much as what preceded Christianity by way of the creations, loves and practices that flow into it and that it redeems, is what it puts an end to by becoming a stumbling block:

I may not relapse into tribal ritual or Pharaoh’s sky-world; Hitler, who tried to do just that, stands revealed as a madman. The other streams are similarly blocked: the modern Greeks, the physicists, and the modern Jews, the Zionists, are certainly not the Greeks or Jews of antiquity. The Greeks glorified the beauty of the universe; our physicists empty it of meaning. The Jews praised God; the Zionists raised a university as the first public building in Jerusalem. So the roadblock of the Word is simply a fact; not one of the streams of the speech of ancient men surges through us directly any more (45).

Rosenstock-Huessy’s reading of history and the role of Christianity as a universalising, planetary forming force stands in complete contradiction to the modern liberal mind which believes it and it alone has found a way to reconcile all the traditions and faiths of the world, thereby illustrating that it is no less a universal dogma than the Christian faith—but it is a dogma that proceeds by deception, the deception of purporting to respect the very traditions it destroys by squeezing their essence into the pre-formations it finds tolerable. Lived faiths are born through and from bloody sacrifices—the blood and sacrifice are as intrinsic to the existence of the faith as to its truth.

Thus, the Jewish Bible and Old Testament and Koran are as bloody books as ever have been written. They are an affront to the vapid comfortableness of the liberal mind which does not want to acknowledge the blood and horror behind its own birth—believing it escapes its reality by virtue of the sanctimony of its moral accusations against its ancestors. In place of harrowing and astonishing testimonies of despair and salvation, of battles and renunciations, of dogmas that require an all or nothing commitment, liberalism distils a religious—moral essence which it drops into an abstract mush. It presents a morally vacuous and existential picture of life’s meaning devoid of real conflictual devotional differences, a safe-space free from micro-aggressions and hate. It presides over the waste land of spirits deprived as much of authority as of their memory.

The liberal spirit is pure tyranny in which all the gods are interchangeable because they have been defanged and folded into the air of ideas and ideals. They are as loveless as they are vacant. They promise the freedom that comes from the right of sensual and racial and ethnic identity in which real differences of the sort thrashed out by Rosenstock-Huessy and Rosenzweig in the midst of war in 1916 are only of importance to the extent they may indicate degrees of demanding, having, and blaming the oppressive privileged Other. This cast of mind is the antithesis of the dialogical spirit as exhibited in the amicably acrimonious exchange between Rosenstock-Huessy and Franz Rosenzweig, an exchange that changed both their minds and opened up new paths for both of them: they both discovered more about their commitments, and priorities, their faiths, what they each held as unnegotiable in so far as they could not lie to themselves about what had made them who they were: and then they joined beyond themselves and beyond their trajects.

One of the most shocking things that we face in the Western world, particularly Western Europe with Muslim immigration is not simply a demographic transformation which the host population has not been prepared for, but the entire process is transpiring without a modicum of understanding being demonstrated in the media or education system about why an encounter must change all parties to it, why that is an opportunity for grace, for new creations of the spirit. Instead, we are witness to a people whose sense of tradition is more than a millennium and a half old encountering a people who have almost entirely lost all sense of communal historical continuity, a people now so spiritually bereft they have little but their stuff and distractions, their escape pathways in booze and drugs and hyper-sexualized culture (that only makes them despicable to Muslim migrants) to show for themselves. Is it any wonder that the Muslim youth are so embittered and willing to embrace causes where they can take direction from a God that lives in their hearts and gives them meaning and purpose that is an alternative to the wasteland that they see all around them?

The liberal narration that predominated among the political and pedagogical classes can only bring to the discussion the same failed abstractions that are tearing itself apart. The Rosenstock-Huessy-Rosenzweig dialogue, as I once said in a lecture in a university in Istanbul, provides the “model” of what a dialogue between inimical faiths must involve. Without such dialogues there can be no friendship, and no birth. But an understanding of the importance of friendship and conflict being in what it gives birth to, again something of such importance to Rosenstock-Huessy, has no meaning in a world in which ideas have supplanted living connections.

Not surprisingly the liberal mind cannot bear to read the Christian Rosenstock-Huessy, preferring to dismiss him as an anti-Semite so that he need not be heard, while the Jewish Rosenzweig is simply reduced to an aesthete and ethicist, a forefather of the pure ethicist Emmanuel Levinas, whose Jewishness never gets in the way of his Greekness, which makes him academically sellable to Jews and Gentiles, who can only look back at past animosities as Christian prejudice and Jewish victimhood. The tyranny of spatial thinking is how it cuts away at the times that provide defining and differentiating characteristics of peoples, and their respective spirits and pathways.