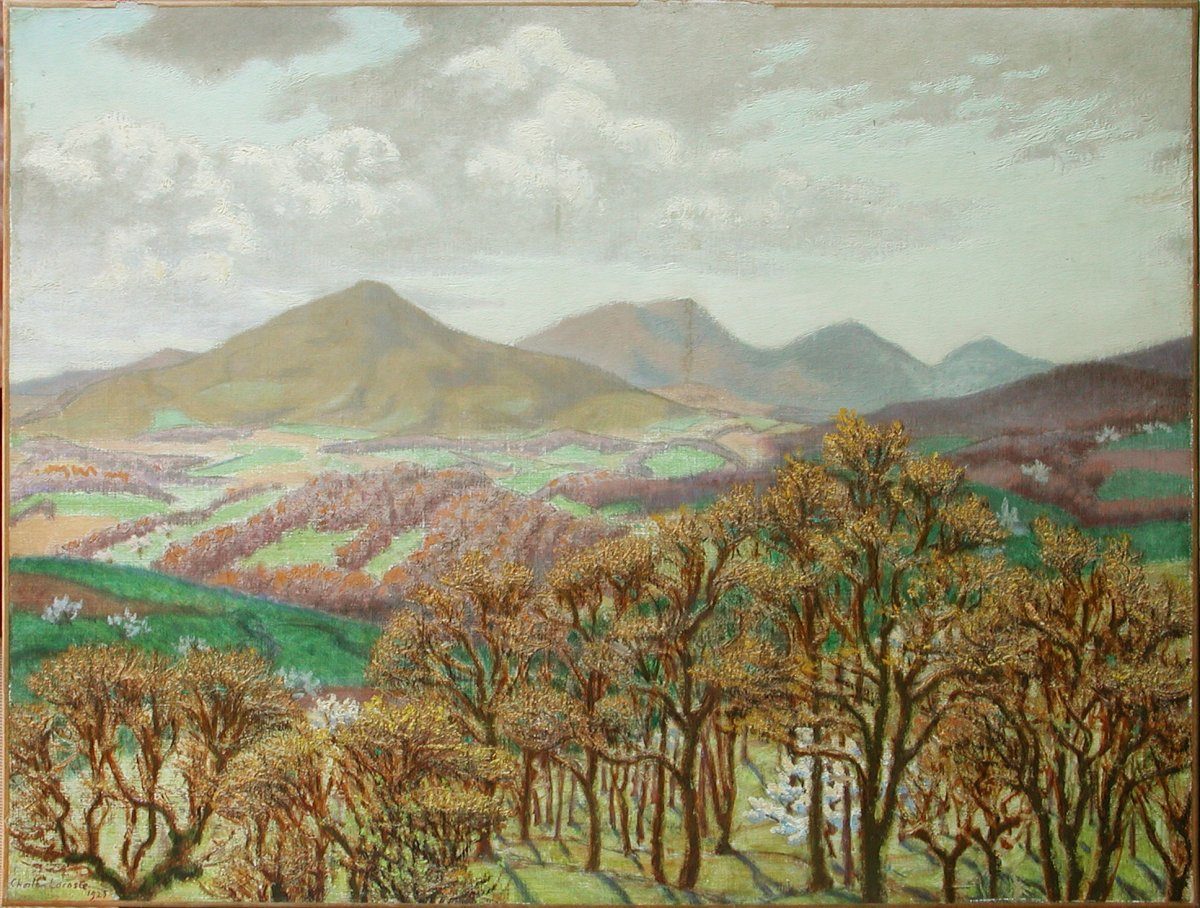

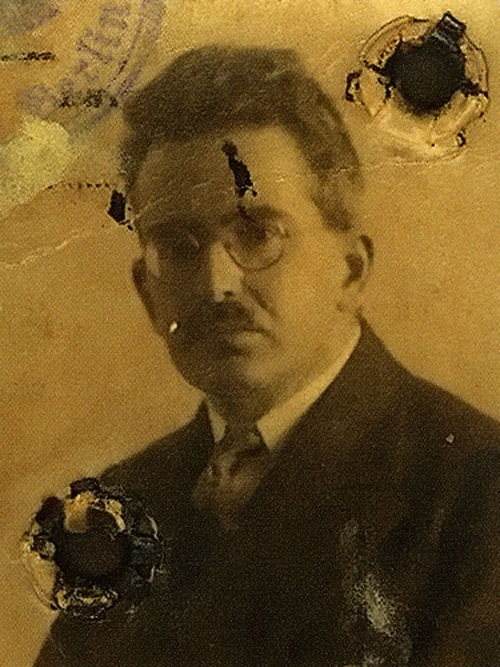

Grégoire Canlorbe continues his intriguing interviews with people who are forging new ways of understanding the world. This time around, he is in conversation with Emil O. W. Kirkegaard, who is a Danish intelligence researcher and freelance data scientist. Learn more at his website. Before you ask—there is no connection with existentialist philosopher, Søren Aabye Kierkegaard. However, Emil Kirkegaard’s great-grandfather, Harald Rudyard Engman, was a Danish dissident, anti-Nazi artist, who was exiled to Sweden during Word War II. The featured image is a work by Harald Engman. We are so very delighted to have Mr. Kirkegaard join us.

Grégoire Canlorbe (GC): Your name is notably associated with the study of stereotype accuracy—especially those stereotypes underlying immigration policy preferences in Danes. How would you sum up your research in this field?

Emil O.W. Kirkegaard (EOWK): It all began some years ago, around the time of my father’s 50th birthday (in 2014). I was visiting Sweden, because his girlfriend is Swedish, and my father decided to rent a house in Skåne, occupied East Denmark, for the birthday party.

Some years prior I had read Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate, and recalled that he made some reference to the accuracy of demographic stereotypes. Checking out the supporting references, I found the same names repeated many times: Lee Jussim and Clark McCauley (all the cited works are in an edited book, Lee et al., 1995). I Googled the names of the authors and found a copy of a book chapter with the great title, The Unbearable Accuracy of Stereotypes. It contained a neat summary of the evidence, as it was at the time (Jussim et al., 2009).

I realized there was an entire scientific literature on this topic, one that wasn’t as stupid as my general impression of social psychology. Recall this was in the middle of the early years of the replication crisis, with priming results falling left and right. After that, I checked out the library (that is, Library Genesis, the Russian pirate library), and found that Lee Jussim had written a book in 2012, Social Perception and Social Reality: Why Accuracy Dominates Bias and Self-Fulfilling Prophecy, and I immediately started reading it (Jussim, 2012). While reading this book, I immediately saw the connection to Bayesianism, which I was familiar with because I had long been reading the blogs from people in the Silicon Valley rationalism movement (focused on LessWrong in those days; now mostly reduced to the Scott Alexander-verse).

Say that you’re judging some person for some trait, say being anti-social. The prior belief is the initial guess about some individual based on whatever demographics one can immediately glance at, whether this is sex, age, country of origin, race, name, clothing and so on.

As such, the question of stereotypes is easy to attack scientifically: simply ask subjects to estimate the group means of various groups, and see how well these line up with reality. In fact, a decent sized, but haphazard, set of studies had been done like this, and they pretty much invariably turned up strong evidence of accuracy (the exception being when the data assumed to represent reality was questionable (see, Heine et al., 2008).

At the same time, I had just started studying immigrant outcomes in Europe, and had in my possession a big dataset from Denmark, where we had crime rates, mean incomes, rates of use of social welfare, educational attainment, and unemployment for some 70 immigrant groups in Denmark, as grouped by country of origin (or of their mothers (Kirkegaard & Fuerst, 2014).

In other words, I had the perfect criterion data to study stereotype accuracy in Denmark, and I knew that similar data existed for other European countries, so there was a way to expand afterwards (Kirkegaard, 2014b; 2015). I then found a way to buy survey data fairly inexpensively. We first conducted a pilot study and found quite large accuracy, despite recruiting unrepresentative people online (such as from my Facebook!).

I then managed to raise some funding from friendly sources, and our first big study was published in Open Psych journals in 2016 (Kirkegaard & Bjerrekær, 2016a; 2016c). I tried to do things right, from the start: large sample size (about 500), pre-registered analyses, and open science practices (open access, data, code, and reviewing).

As mentioned above, I was familiar with the replication crisis issues in social psychology and did not want to contribute to such poor practices. I also knew that my results would get attacked by leftists, and thus had to be extra strong to withstand scrutiny (Gottfredson, 2007; Kirkegaard, 2020). However, our results were crystal clear—the main aggregate stereotype correlated r = .70 with real differences—and the results were closely in line numerically with the findings that Lee Jussim had summarized.

The idea of linking this data to the immigration preferences was good, and obvious in hindsight, but it wasn’t mine. Noah Carl was the first to combine the two ideas in his 2016 paper, also in Open Psych (Carl, 2016). After reading his paper, I knew the next step forward was to measure all three variables in a single study: real group differences (insofar as government data can tell), stereotypes (estimates of those differences), and finally policy preferences for the same groups.

When looking at immigrant groups, it was obvious that popular opposition to immigrants was closely in line with the actual immigrant groups with high rates of social problems, whether crime or welfare dependencies (so in practice, against Muslim groups). I teamed up with Noah for a study like this, and we wanted to get it out somewhere “mainstream.”

So, we tried a bunch of social psychology journals; with not much luck. One editor, Karolina Hansen, at a Polish university, told us we needed to explicitly state, multiple times, that Muslims were not causing their own misfortunates, whereas our study was agnostic on this topic. I guess I should not be so surprised since, despite being in Poland, she has a Danish last name, so was probably infected by the Woke memeplex.

Unfortunately, it was around that time that troubles began for Noah Carl, and he had to divert time to defending himself against the communist campaign and its friends in the media (Carl, 2019). It didn’t end well; and he was fired. We managed to finally publish this work in 2020 (Kirkegaard et al., 2020).

To return to the question, I would say that my work in this field has just begun, and I expect to publish a bunch more studies on immigrants, stereotypes and their links to intelligence. We are currently finishing up a big study in the Netherlands, with similar results. The last part is important, because from an intelligence research perspective, having accurate stereotypes is simply a manifestation of the general factor of intelligence, already strongly correlated with general knowledge.

So, one should see pervasive correlations between stereotype accuracy and intelligence. And, in fact, that is the case. Some left-wing psychologists and their media cheerleaders hilariously tried to brand this as a negative aspect of intelligence (Khazan, 2017; Lick et al., 2018; Sputnik News Staff, 2017).

GC: A well-known investigation of yours deals with the dataset of OKCupid’s users. You especially focus on the association of cognitive ability with self-reported criminal behavior—and with religiousness. Could you tell us more about it?

EOWK: Back in 2010, or thereabouts, I discovered the OKCupid dating site, and used it myself. The dating site really was very special, as no other dating site collected so much interesting data on their users. Most dating sites attempted only crude social matching, or even dumber things like astrological signs. However, OKCupid was started by a mathematician, and he had a better idea, despite having no background in psychology.

As a big fan of open science, I was wondering how to get a copy of the data for my own curiosity. I teamed up with a programmer to do a scraping (automatic download) of the website, and we managed to download data from nearly 70,000 users. Mind you, a lot of these profiles are essentially empty and not useful. But still, the dataset is amazing, and one can typically use about 10-30k users in a study, depending on which variables are desired and which subgroups.

Again, in the spirit of open science, we wanted to share this data with the world, so we sent our paper to review at Open Psych (Kirkegaard & Bjerrekær, 2016b). I don’t recall exactly how it happened, but some mainstream social psychologists started retweeting my tweet to the data (e.g., Brian Nosek of OSF), and eventually the SJWs joined in (Oliver Keyes was a notable nutty blogger who wrote some rambling blogpost on this, since apparently deleted), or maybe the other way around.

In any case, it ended up being a global media event of sorts, where we got featured in various big outlets: Wired, Forbes, Vox, Vice, even Fortune magazine. A guy I went to school with, in 2006, called me and wanted some input for an article he was writing for the Danish state media. The data on the website was really already public, and just required a free user (some of it). It’s just that when this data sits in 70,000 profiles, it is not as useful for analysis as when it is in a spreadsheet-type format. The task of scraping could be done by a chimpanzee, and involves visiting random profiles and copypasting the data into a big spreadsheet. In fact, the website itself wrote in its user agreement that users should consider the data public (“You should appreciate that all information submitted on the Website might potentially be publicly accessible. Important and private information should be protected by you”).

In the end, OSF deleted the copy of the dataset on their service, following a copyright complaint from OKCupid’s owners. Someone reported me to the Danish data protection agency, and they sent me some questions in a threatening manner, which I didn’t answer; and then after a few months, they gave up the case. The media never reported on this dropping of the case. So, in the eyes of the media and the public, it appears I was accused and presumed guilty of some crime; when, in fact, a case was not even filed against me in court.

Aside from all, the dataset is really quite something. This is because the questions on the site were mostly made by users themselves; and because of this, some of them asked about things that psychologists would not dare to ask about. They are also a lot more diverse in topics than what interests psychologists. We have published some studies looking at intelligence estimation based on some 14 questions with high g-loadings; and intelligence scores from these do in fact relate to religiousness, crime (self-reported, not optimal), political interest and so on, in the usual ways (Kirkegaard, 2018; Kirkegaard & Bjerrekær, 2016b; Kirkegaard & Lasker, 2020).

This is doubly interesting because the data was filled out by users knowing well that other users would be reading their answers; thus suggesting that social desirability bias should be large here. Evidently, it is not large enough to remove the usual associations. Later on, the website got bought out by Big Dating, that also owns Tinder and others, and the website is now a low quality clone of Tinder; a shell of its former glory. Sad! The most interesting remnant of the website, aside from this (unfortunately) partial copy of the site’s database (and others that exist), is that the founder wrote a book on some analyses he did (Rudder, 2015). It’s really a commercialization, and not a very good at that, of the old OKTrends blog. Fortunately, internet polymath Gwern has archived the blog, so people can, and should, read the unredacted analyses.

GC: Your university background is linguistics. Do you believe race differences may be manifested in language? What are your thoughts about Umberto Eco’s remark that “the language of Europe is translation”?

EOWK: I did a bachelor degree in linguistics, starting in 2010. Before that I studied philosophy for two years, but I was disillusioned with that department and the field, and did not finish the degree. I was always good with language in school, and since I was already interested in the philosophy of language, branching out to linguistics was not a big step.

Honestly, though, studying linguistics had a big advantage: there were no class attendance requirements, so I could avoid going to classes (these are a waste of time). This freed up a huge chunk of time, and allowed me to sleep during the day and work at the night, whenever this was practical (I have non-24 disorder). Passing exams was really mostly a matter of writing three essays (10-15 pages in length) every 6 months, one for each class that one took that semester. Each class was usually based on some book or some papers, which you read. All in all, writing a paper takes perhaps two days, editing included, and reading the required material takes maybe another three days; so we’re looking at about fifteen days of work every 6 months.

In Denmark, the state pays students a stipend to study, about US $800, and there is low-cost, subsidized student housing available too. So, this income is livable; and one can even invest some of it in Bitcoin on the side (Moon Inc.). The rest of the time, I used unwisely to play too much on the computer. But still a large proportion of the time I used to self-study psychology, genetics, statistics and programming. When I was doing the master’s (candidate) in linguistics, in 2015, I was already good enough that a high-profile professor wrote to recruit me for his startup in genetics. That ended my career in academia, not that I was keenly interested in pursuing a linguistics PhD.

So, with my unusual linguistics background aside, what about race and language? It’s hard to say because linguists are, generally speaking, non-quantitative people, and don’t look at these things, except in bland ways. There are some findings on how the physical shape of humans differ by race, and this affects the sounds they produce. Africans have notably larger lips and a broader nose (for cooling), and this results in slight differences in the sounds they make. I don’t think this is very important, however.

More interesting in the big picture are associations between culture and language (an extreme version is called linguistic relativity); and of course, some cultures are vastly more complex than others. Some languages are really quite simple, lacking words for most scientific concepts, some for even basic mathematics, like counting. I am not aware of any formal study of ethnic group IQs and their language features. Economists conduct these kinds of studies, trying to spot relationships between psychological traits and languages, and how this should be reflected in economic outcomes. Best thing they have come up with is that languages that allow dropping of pronouns are higher in some good stuff (Feldmann, 2019; He et al., 2020; Mavisakalyan & Weber, 2018).

There is a big dataset of language features called The World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS), which is used to study this stuff (the field is called linguistic typology). It has data for some 2700 languages last time I looked, and these are given geographical coordinates, countries, and so on. One could match this to ethnic IQs and national IQs, failing that, and maybe something useful would come out of this. Honestly, I have not looked, because I don’t think anything interesting will come out of it. I did take an initial look at the data from a quantitative perspective in a preprint never published (not even submitted anywhere, (Kirkegaard, 2021); I posted it as a formal preprint for the purpose of this interview).

The national data is rather small for languages, because of the extensive family relationships between them. So, the effective sample size is less than the number of countries. Biologists are familiar with this problem, and have standard phylogenetic regression methods to handle it, and linguists also (they do it in a worse way), but economists less so. I think it is better to proceed here with ordinary national IQs work, and expanding to the genetics of these, á la what Davide Piffer has been doing since 2013 (Piffer, 2013; 2015, 2019, 2020a, 2020b), and what we did in our big 2016 paper looking at the genetic ancestry of countries and their subdivisions (Fuerst & Kirkegaard, 2016). I am not familiar with Umberto Eco, so I have no comment on that quote.

GC: As an avowed proponent of eugenics, do you share the belief in COVID-19 pandemic’s purifying role? What is your assessment of the reservations on negative eugenics that Charles Darwin—while acknowledging the attenuation of natural selection in Victorian England—expressed in The Descent of Man? Namely that “the surgeon may harden himself whilst performing an operation, for he knows that he is acting for the good of his patient; but if we were intentionally to neglect the weak and helpless, it could only be for a contingent benefit, with an overwhelming present evil.”

EOWK: COVID-19 almost only kills old people who are no longer reproducing, so it has no eugenic or dysgenic effect. If one wanted to be really cynical, one could say that by killing off a bunch of unproductive people, it is easing the state’s welfare budgets, though causing large initial costs in healthcare.

I agree with Darwin. There is an uneasiness with realizing the problem of dysgenics and doing anything about it. Galton himself commented on this in his autobiography (1908): “Man is gifted with pity and other kindly feelings; he also has the power of preventing many kinds of suffering. I conceive it to fall well within his province to replace Natural Selection by other processes that are more merciful and not less effective.” So, how can we do things more mercifully? Many have thought about this problem (Glad, 2004).

I submit that we don’t need to do too much. Some countries have already managed to reduce the intelligence-fertility relationship to quite a weak negative or null association through existing social policies and cultural changes (Kolk & Barclay, 2019; Meisenberg, 2008; Reeve et al., 2018).

Aside from that, we have the tools at hand to reverse the problem: embryo selection and genome editing. With the latter, we can edit embryos to remove some known errors, insofar as these are known (typically well-known genetic disorders). The former technology has been here for years, but needs to be augmented with a modern genomics approach, and to get rid of the communist ethos that prevents this from happening (Anomaly, 2018; 2020; Anomaly & Jones, 2020).

Interestingly, survey evidence shows that large fractions of the world population, with notable differences between countries, are already in favor of such technology, and this fraction is increasing over time, just as it did when the original IVF technology emerged (Pew Research Center, 2020; Zigerell, 2019). On the technology side, we need to figure out how to produce a lot of egg cells (sperm are plenty!), and combine these with the best sperm cells if possible (sperm selection), nurture the resulting embryos, and pick the best combination of genes among the sibling embryos according to the best genetic prediction models.

This approach was outlined in Gattaca back in 1997, so this is hardly new. We just need to get serious about it. Galton suggested the same more than 100 years ago (“I take Eugenics very seriously, feeling that its principles ought to become one of the dominant motives in a civilised nation, much as if they were one of its religious tenets”).

If we let the power of capitalism achieve this, we can all have healthier, smarter, prettier, more creative children, and work towards improving our Kardashev score. Considering the current way Western elite thought is moving, there is probably not so much hope for this. Richard Lynn made similar forecasts in his 2001 book, Eugenics: A Reassessment.

GC: A nation’s collective intelligence partly lies in its average IQ. It also lies in its ability to network the various individual IQs within it in an efficient way, i.e., in a way allowing the nation to solve challenges and to prevail in intergroup competition. Efficient networking within a national brain notably includes intragroup competition for innovation—and the shifting of resources towards sound innovators, i.e., individuals bringing a way of thinking which is different, novel, but also more efficient than the previous admitted thought patterns. Do you sense a correlation between average IQ and efficient networking? Historically, which nation performed best in terms of intragroup cognitive collaboration?

EOWK: It’s a tough question because competing nations throughout history have not generally been so easy to compare, since they differ in population size, and change their borders and thus populations over time as well (e.g., modern Austria vs. Austria-Hungary vs. Greater Germany). The ultimate test of inter-group competition is warfare, and so one can look at which countries are very good at this, or have good standing militaries (Karlin, 2020). One can go beyond looking at who won a lot of wars.

One can look at efficiency specifically, and for World War II, there are some numbers here on the combat efficiency of soldiers from the warring states. Though these were calculated by the US army after the war, it probably won’t surprise many to learn that Nazi Germany’s soldiers were the most efficient in per capita terms. Specifically, the research computed the worth of a solider, setting the Nazi German one to 1.00, yields values of 1.10 Americans, 1.45 British, and >4 Slavic (Polish or Russian) (Kretaner, 2020; Turchin, 2007). Details of the calculations are hard to find, and I have been unable to find numbers for World War I or any other wars.

But I admit to not being a military historian and not having spent more than a few hours looking. Peter Turchin talks a lot about this collective efficiency. He uses the term, Asabiya for this, from the great Islamic golden age thinker, Ibn Khaldun. We can make some guesses though. Group efficiency is higher when people have a feeling of belonging.

Most academic research finds negative effects of ethnic/race diversity on social trust (Dinesen et al., 2020), and given the iniquitousness of ethnic voting in democracies, and the endless anti-European hatred from the European left, it’s hard to disagree with a diagnosis of an overall negative effect of ethnic diversity on collective effectiveness.

We currently live in a time of extreme political polarization (mostly Europeans versus other Europeans in the same countries), mostly caused I think by the radicalization of the global media by communist Woke theories from academia. Zach Goldberg is doing great work on this topic (Goldberg, 2019a; 2019b).

China, on the other hand, is going strong in terms of collective efficiency, insofar as their human capital allows (corruption is endemic outside WEIRD populations; (Henrich, 2020)). All this aside, collective efficiency is positively affected by national average intelligence, and this shows up in any kind of analysis one does. Intelligence is at the individual level related to trust, honesty, competence at any job, patience and so on. So, it is not surprising that countries with smarter people outcompete others by large margins (Kirkegaard & Karlin, 2020).

GC: You dedicate yourself to exploring the relationship of personal names to factors like social status, intelligence, age, and country of origin. What are your conclusions at it stands? Do you subscribe to the Jewish belief that someone’s name predicts his destiny?

EOWK: I’ve never heard of this Jewish belief, but it is certainly true that names have associations with outcomes in life. You see when most social scientists discover such patterns, they immediately think it results from some kind of discrimination (the so-called second sociologist fallacy: any group difference is caused by discrimination by the above average groups). They devise experiments to show that people preferentially hire people with higher status names, and so on (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004; Oreopoulos, 2011). Yes, I am sure one can find some evidence of this stuff. It goes back to the stereotype discussion initially. People act in a crudely Bayesian manner; they use whatever information about an individual they can find. Sometimes researchers give people only names, and so of course people will use such information until they can get better information. This is both rational and not a big mystery.

My entry into this topic was, again, due to nice data presenting itself, but in a less useful format. A Danish newspaper bought government statistics about first names of people living in Denmark, specifically about their average incomes, crime rates, and so on. This data were then published on a website, sort of. There was a search function and one could look up any name to see the stats for that name; but no way to download all the data.

Together with a friend, we figured out how to get the entire dataset behind this website. We then carried out a bunch of analyses of this. We confirmed the usual “S factor” pattern. Maybe we should call this Thorndike’s Rule, as he wrote in 1920: “a still broader fact or principle—namely, that in human nature good traits go together. To him that hath a superior intellect is given also on the average a superior character; the quick boy is also in the long run more accurate; the able boy is also more industrious. There is no principle of compensation whereby a weak intellect is offset by a strong will, a poor memory by good judgment, or a lack of ambition by an attractive personality. Every pair of such supposed compensating qualities that have been investigated has been found really to show correspondence.” (Quoted from Gwern’s page on correlations).

Anyway, in our data, names with higher mean incomes were also, on average, less crime prone, and worked better jobs and so on (Kirkegaard & Tranberg, 2015). So, for every name, one can score it on this composite measure of social status, or “general socioeconomic factor,” as I called it in 2014 (Kirkegaard, 2014a), in a study of countries. I got the idea from reading Richard Lynn and Gregory Clark’s books in short succession (Clark, 2014; Lynn & Vanhanen, 2012). Clark talks about how everyone is born with a latent, genetic score for this generalized social status; and the various social status indicators in life are an imperfect indicator of this (and the other part being mostly luck).

However, if one relies on last name data, one can actually see that the heritability of the latent general social status is about 75%. This finding replicates across many datasets from different countries, even in Maoist China. It’s really quite astonishing. I realized then, that the same thing can be said for countries and subpopulations inside countries, such as immigrant groups (Kirkegaard & Fuerst, 2014).

In our follow-up study, we were also able to show that average intelligence measured in the Danish army correlated quite well with this general social status of names (Kirkegaard, 2019). Personally, I don’t think having a funny name does much to harm one’s career; and it’s a quite simple matter to change it these days, if one really thinks so.

The fact of the matter is rather than funny parents give their kids funny names, and low status parents their kids low status names, and so on. This results in first names being differentiated by genetic propensity for social status, despite not being a family. One can even see dysgenics this way in our Danish data, as higher social status names had fewer “kids;” a kind of pseudo-fertility measure; and so these reduce their share of the population over time. Elite families dying out is a familiar finding for many historians.

GC: It is sometimes asked whether our ontological concepts (causality, identity, quantity, and so on) are intended in the human mind to relate to objective properties of the observed things. Or, on the contrary, only serve as molds, allowing the human mind to clarify, organize the empirical data; but having nothing to do with the content of reality. It is also asked whether the human mind is able to draw its concepts from an immaterial dimension reached through suprasensible perceptions. Or, on the contrary, is condemned to rely on itself—and on sensible experience. What is your take on such issues?

EOWK: That philosophy is a waste of time. For those few who still want to wade into this territory, I highly recommend Alan Sokal’s writings on ontological realism, quantum mechanics and postmodernism (Sokal, 2008; Sokal & Bricmont, 1999).

In my opinion, the best philosophy is written by working scientists or philosophers with a very close relationship to science (and I don’t mean doing some pop-neuroscience). For those wanting to put a label on me, I like to refer to myself as a neo-positivist scientific realist. This is essentially the view that evolution favors organisms that have some level of accuracy of their perception of the real world, which come equipped with a bunch of mostly adaptive cognitive biases (“tinted glasses”), and that through rigorous application of the scientific process, we can better see reality as it really is.

Unfortunately, I don’t think that social science is close to this scientific ideal, being staffed by the wrong people, with the wrong incentives. Social science would do better if we fired everybody who works there, and hired some random physicists to figure things out. This is essentially what Dominic Cummings did in order to win the 2016 Brexit vote, his blog has a bunch of stuff on this.

GC: Going back to linguistics, you may have heard of the proposition “Est vir qui adest.” Namely the anagram for Pilate’s question to Jesus, “Quid est veritas?” What does such connection inspire to you? Which one of Jesus or Pilatus is the chad—and which one the virgin?

EOWK: I generally don’t read fiction, so I am not overly familiar with the Bible stories. Considering that Jesus supposedly died as a childless Virgin (if we disregard the Mary possibility), and Wikipedia tells me that Pilate apparently had a wife, and we don’t know anything about any potential children. So, it boils down to the interesting question of whether Jesus was as holy as he claims to be (i.e., the Gospels claim him to be!), considering the base rate of fertility rates among cult leaders. On the balance of probabilities, I am going with Chad Jesus and the groupies theory, and may God forgive my atheist sins!

GC: Thank you for your time. Would you like to add something?

EOWK: These were some very far reaching questions. You certainly have a talent for interviewing. Maybe you can get a job at Playboy!

The featured image shows, “Nyboder with figures, evening,” by Harald Rudyard Engman, painted in 1931.