High in the steeple the bells were conversing. Two of the younger ones were vexed and spoke angrily, “Is it not time we were asleep? It is almost midnight, and twice have we been shaken, twice have we been forced to cry out through the gloom just as though it were day, and we were singing the call for Sunday Mass. There are people moving about in the church; are we going to be tormented again, I wonder? Might they not leave us in peace?”

At this the oldest bell in the steeple said indignantly, in a voice which though cracked had lost none of its solemnity, “Hush, little ones! Are you not ashamed to speak so foolishly? When you went to Rome to be blessed, did you not take an oath, did you not swear to fulfil your duty? Do you not know that in a few minutes it will be Christmas, and that you will then celebrate the birth of Him whose resurrection you have already celebrated?”

“But it is so cold!” whimpered a young bell.

“And do you not think that He was cold, when He came into the world, naked and weak? Would He not have suffered on the heights of Bethlehem had not the ass and the ox warmed Him with their breath? Instead of grumbling and complaining, let your voices be sweet and tender in memory of the canticles with which His mother lulled Him to sleep. Come, hold yourselves in readiness. I can see them lighting the tapers; they have constructed a little manger before the Virgin’s altar; the banner is unfurled; the beadle is bustling about. He has a bad cold, the poor man; how he sneezes! Monsieur le Curé has put on his embroidered alb. I hear the approaching sound of wooden shoes; the peasants are coming to pray. The clock is about to strike the hour—now—Christmas! Christmas! Ring out with all your heart and all your might! Let no man say that he has not been summoned to midnight Mass.”

II.

It had been snowing for three days. The sky was black, the ground white; the north wind howled through the trees; the ponds were frozen; and the little birds were hungry. Women, wrapped in long mantles of brown wool, and men in heavy cloaks slowly made their way into the church. They knelt and with bent brows murmured the answer as the priest said, “And the Lord said unto me, ‘Thou art my Son, whom this day I have begotten.'” The incense was smoking, and blossoms of hellebore, which are the roses of Christmas, lay before the tabernacle in the light of the tapers. Behind one of the pillars, near the door of the church, knelt a child. His feet were bare. He had slipped off his wooden shoes on account of the noise they made. His cap lay on the floor before him and with clasped hands he prayed, “For the soul of my father who is dead, for the life of my mother, and for me, for your little Jacques, who loves you, O my God, I implore you!” And he knelt all through Mass, lost in the fervor of his devotion, and rose only when he heard the words,—

“Ite missa est.”

The people crowded together under the exterior porch. Every man lighted his lantern, and pulled up the collar of his cloak; and the women drew their mantles closely around them. Brrr! how cold it was! A little boy called out to Jacques, “Are you coming with us?”

“No,” said he, “I have not time;” and he started off on a run. He could hear the village people far away singing the favorite carol of olden France as they walked home,—

“He is born, the Heavenly Child.

Ring out, hautbois! ring out, bagpipes!

He is born, the Heavenly Child;

Let all voices sing his advent!”

III.

Jacques reached the thatched cottage at the far end of the hamlet, nestling in a rocky hollow at the foot of the hill. He opened the door carefully, and tiptoed into a room in which there was neither light nor fire.

“Is that you, little one?”

“Yes, mother.”

“I prayed while you were praying. You must be half asleep; go to bed, child. I do not need anything. If I am thirsty, I have the water-jug here where I can reach it.”

In a corner of the room near Marguerite’s bed, Jacques turned over a litter of ferns and dry grasses, stretched himself upon it, drew the ragged end of a blanket over him, and fell asleep. Marguerite, however, did not sleep. She was thinking, and her thoughts wrung tears from her eyes. She was evoking the happy days when her husband was with her, and life seemed so full of hope. She lay still, so as not to waken her boy, her head thrown back on the bolster, the tears trickling off her bony cheeks, her hand pressed to her hot chest.

Marguerite’s husband had been the pride of his village, a hard worker and an upright man. At the call of the Conscription he went to the wagon train, for he was a good driver, kind to his horses, a man who made his own bed only after having prepared their litter. He spoke with pleasure of the time when he had been “in the army of the war,” and would say laughingly, “I carted heaps of glory in the Crimea and in Italy.” His return to the village was a source of rejoicing. He had known Marguerite as a child; he now found her a woman, and married her. They were poor, Marguerite’s trousseau consisting of a three-franc cap, which she bought in order to make a good appearance at the church ceremony. They owned the cottage,—a miserable, dilapidated hut; but they were happy in it because they worked hard and loved each other. The village people said, “Marguerite is no simpleton. She knew what she was about when she married Grand-Pierre. The sun does not find him abed. He is strong, saving too, and no drunkard.”

Yes, Grand-Pierre was a good workman, spry, punctual,—a man of much action and few words. He had resumed his old trade, and drove his teams through the mountains for a man who was quarrying granite. He drove four stout-haunched, wide-chested horses, and excelled in manœuvring the screw-jack, in balancing the heaviest blocks, and driving down the steep declivities that opened into the plain. When he came home after his day’s work, he found the soup and a jug of cider on the table, and Marguerite waiting for him. Everything smiled upon them in the poor little home, where there was soon a willow cradle.

But happiness is short-lived. There is an Arab proverb that says, “As soon as a man paints his house in pink, fate hastens to daub it black.” For eleven years Pierre and Marguerite lived happily together and laid their plans with no fear of the future. Then misfortune came and made its home with them. One raw, foggy winter’s day Grand-Pierre went out to the mountain. He loaded his wagon; and after having left the dangerous passes of the road behind, he sat on the shaft for a rest, and leaned against a great block of granite. He was tired; and lulled by the swaying of the vehicle and the monotonous jingle of the bells, he involuntarily closed his eyes. After a little the left wheel went over a great limb that lay across the road. The shock was violent. Pierre was pitched from his seat; and before he could move, the heavy wheels rolled slowly over him and crushed in his chest.

The horses went their way unconscious of the fact that their driver, their oldest friend, lay dead behind them. They reached the quarriers and stopped at the door.

“Where is Grand-Pierre?”

Inquiries were made at once. Men were sent to the cottage. Marguerite grew anxious. As the light failed, they took torches and went up the mountain, shouting, “Hello there, Grand-Pierre!” but no voice answered. At last they came upon the poor man lying in the middle of the road on his back with outstretched arms. The wheels had cut through the cloak and the edge of the rent was crushed into his chest and black with blood.

All the villagers followed the corpse to the church and the cemetery, and held out their hands to Marguerite, who stood white and immobile, like a statue of wax, muttering mechanically under her breath, “O God, have pity! have pity!” Jacques was then in his tenth year. He could not appreciate the greatness of his mother’s sorrow, and only cried because she did.

Then misfortune had followed misfortune,—poverty, illness, misery. And so through this Christmas night Marguerite lay stifling her sobs as she recalled the past.

IV.

Jacques rose at dawn, shook off the dry grasses that stuck to his hair, and went over to his mother. Her eyes were half closed, her lips very white, and there were warm red spots on her cheeks. When she saw the boy, she made a faint movement with her head.

“Did you sleep, mother? Do you feel well?”

“Yes; but I am very cold. Make a little fire, will you?”

Jacques searched every corner of the hut, looked in the old cupboard, went through the cellar which had formerly contained their supplies, and said,—

“There is no wood left; and there are no roots either.”

“Never mind, then. It is not so very cold, after all.”

Jacques picked up a stone, hammered at the nail that secured the strap of his wooden shoe, slipped his foot into it, pulled his cap down over his ears, and said resolutely,—

“I am going out to the mountain to get some dead wood.”

“Why, you forget that to-day is Christmas, my child!”

“I know; but Monsieur le Curé will forgive me.”

“No, no, you must not go; it has been prohibited.”

“I will see that the rural guard does not catch me. Please let me go; I will be back soon.”

“Well, go, then.”

Jacques put his pruning-knife in his pocket, threw a rope over his shoulder, and opened the door. A gust of wind thick with snow dashed him back and whirled through the room.

“What a storm!”

“Holy angels!” cried Marguerite; “it is the white deluge! Listen, little one: you are not warm enough. Open the old chest where your father’s things are, and get his cloak,—the cloak he had on when they brought him home. Wrap it around you, and see that you do not take cold. One sick person in the house is enough.”

Jacques took the cloak, upon which a twig of blessed box had been laid. It was one of those great black and white cloaks of thick wool and goat-hair, with a small velvet collar and brass clasps. There was a gaping black rent in it, and here and there an ugly dark spot. It was very long for Jacques, so Marguerite pinned the edges up under the collar. When he was halfway out of the door she called out to him,—

“Jacques, if you pass the Trèves do not forget to say a prayer.”

V.

Jacques started off at a brisk pace. There was not a human being to be seen anywhere. The fields were gloomy and desolate. The snow seemed to shoot along horizontally, so violently was it lashed by the north wind. On the high, frosted limb of a poplar a raven was croaking. Jacques stopped every now and again to knock off the snow which gathered and hardened on the soles of his wooden shoes. He was not cold, but he found his cloak very heavy. He had gone a long way and had reached the first undulations of the mountain, the edge of the forest, when he stopped petrified before the rural guard, who appeared suddenly at a turn in the road, imposing with his cocked hat, his sword, and the word “Law” glittering on his belt.

This Father Monhache, who had been a sapper before he became a rural guard, was greatly dreaded in the land. He was the terror of the village boys, for whenever he found any of them stealing apples, shaking the plum-trees, or knocking down nuts, he swore at them terribly, and then led them by the ear to Monsieur le Maire, who sentenced the delinquents to a paternal spanking. Jacques was therefore aghast when he found himself face to face with this merciless representative of the authority.

“Where are you going, Jacques, in this devil of a storm?”

Jacques tried to concoct some story to explain his expedition; and before he had decided which would be the most effective, he caught himself saying simply,—

“I am going to the mountain, Father Monhache, to get some dead wood. We have none at home, and my mother is ill.”

The old guard dropped an oath and said in a voice which was by no means harsh,—

“Ah, so you are going to the mountain for dead wood, are you? Well, if I meet you in the village this evening with your fagot, I will close one eye and wink the other, do you understand? And if you ever tell anybody what I said, I will pull your ears.” And he walked off with a shrug. He had not gone ten feet when he turned and shouted, “There is more dead wood in the copse of the Prévoté than anywhere else.”

VI.

“He is not such a bad man, after all,” thought Jacques.

He was now climbing the mountain, and it was a hard struggle for his little legs. Every now and then he heard what he thought was a moan in the distance,—the breaking of a limb under the weight of the snow. Look as he would through all those branches, he could not see a single blackbird, nor even a jay. Not a little mouse ran along the slope. A few intrepid sparrows alone, black spots on the white ground, hopped about in search of food.

Measuring his steps to the time, Jacques began to sing in a low tone,—

“He is born, the Heavenly Child,—”

and walked along with a great effort, leaning forward. He sunk into hollows where the snow was deep. He knew that he was not far from the copse of the Prévoté, so he took courage, though he stubbed his foot against the hard, concealed ruts, and tumbled into holes. Father Monhache was right; there was surely no lack of dead wood at the copse of the Prévoté.

Over the shivering heather and the crouching brier, lay the fallen branches in their furrows. Jacques fell to work; and how he toiled! He had taken off his cloak, that his movements might be freer. His legs sunk deep in the snow. His hands and his arms were drenched and chilled, while his face was hot and wet with perspiration. He would stop every minute or two to look at his pile of wood, and think of the bright flame it would make in the hut.

When he had all he could carry, he tied it in a fagot, threw his cloak over his shoulders, and started along the shortest cut to the village. His legs trembled. Now and then he was compelled to stop and lean against a tree.

VII.

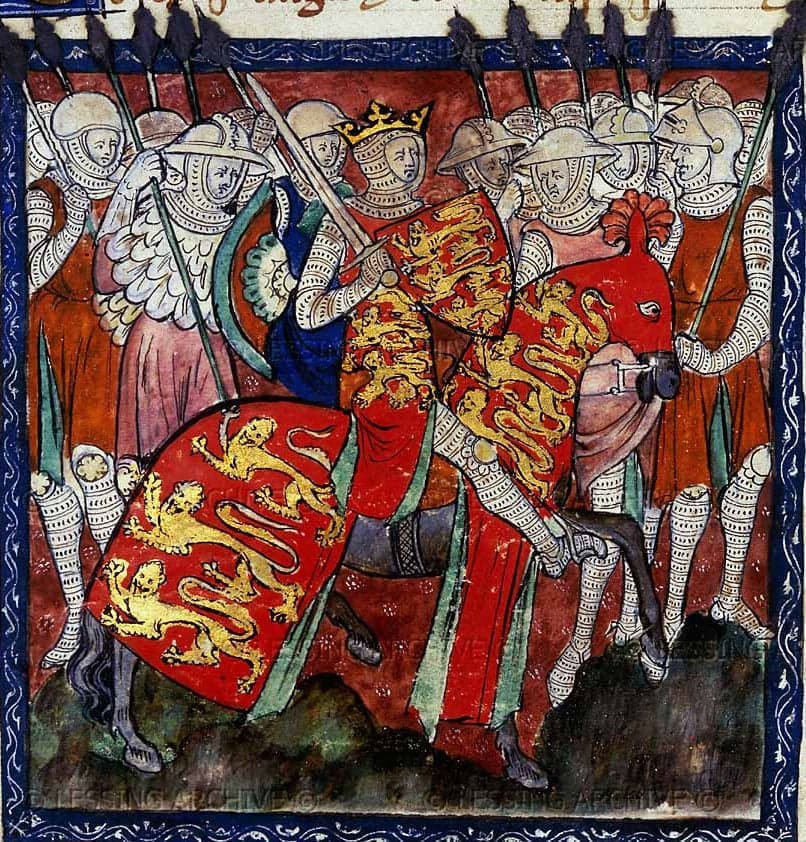

After a little he came to a cross-road. This was Trèves. In the days of the Romans it had been called Trivium, because of the three roads that met there. On that spot had formerly stood an altar to Mercury, the protector of roads, the god of travellers, and the patron of thieves. Christianity had torn down the Pagan altar and replaced it by a crucifix of granite. On the pedestal, gnawed by lichens, one may still find the date, A. D. 1314. During the Hundred Years’ War the statue was shattered, and the cross-road strewn with its fragments. Then, when the foreign element which sullied our land had been cast out, when “Joan, the good maid of Lorraine,” had returned the kingdom of France to the little king of Bourges, the statue was raised, and from that time it has been the object of special veneration through the country. Every peasant bows before it, and even the veterinary, who delights in laughing at priests, would not dare pass the Trèves without raising his hat.

With his hands nailed to the cross, his brow encircled with thorns, the Christ hangs, as though he were calling the whole world to take refuge in his outstretched arms. He seems enormous. In the folds of the cloth which girds his loins wrens have built nests that have never been disturbed. His face is turned toward the East; and his hollow, suffering gaze is fixed upon the sky, as though he were looking for the star that guided the Magi and led the shepherds to the stable in Bethlehem.

VIII.

Jacques did not forget his mother’s instruction. He laid down his fagot, took off his cap, and there, on his knees, began a prayer, to which the wind moaned a dreary accompaniment. He repeated some prayers which he had learned at the Catechism class; he said others too,—fervent words that rose of themselves from his heart. And as he prayed, he looked up at the Christ, lashed by the storm. Its parted lips and upturned eyes gave it an expression of infinite pain. Two little icicles, like congealed tears, hung on its eyelids, and the emaciated body stretched itself upon the cross in a last spasm of agony. Jacques began to suffer with the suffering embodied there, and he was moved to console the One whom he had come to invoke.

When his prayers were said, he took up his fagot and started on his way; but before he had left the cross-road behind him, he turned and looked back. The Christ’s eyes seemed to follow him. The face was less sombre; the features seemed to have relaxed into an expression of infinite gentleness. A gust of wind shook the snow that had accumulated on its outstretched arms. One might have believed that the statue had shivered. Jacques stopped. “Oh, my poor God,” said he, “how cold you are!” and he went back and stood before the crucifix. Then with a sudden impulse he took off his cloak. He climbed upon the pedestal, then putting his foot upon the projection of the loin-cloth, and reaching about the shoulders, he threw the cloak around the statue.

When he had reached the ground again, “Now, at least, you will not be so cold!” said he; and the two little icicles that had hung on the eyelids of the divine image melted and ran slowly down the granite cheeks like tears of gratitude.

Jacques started off at a rapid pace. The cruel north wind blew through his cotton blouse. He began to run, and the fagot beat against his shoulders and bruised them. At last he reached the foot of a declivity and stopped panting by a ravine sheltered from the snow and the wind by a wall of pines. How tired he was! He descended into the ravine and sat down to rest, only for a minute, thought he,—just a minute more, and he would be up again and on his way to his mother. How tired he was! His head, too, was very hot, and felt heavy. He lay down and leaned his head against the fagot. “I must not go to sleep,” he said. “Oh, no, I will not go to sleep;” and as he said this, his eyelids drooped, and he became suddenly engulfed in a great flood of unconsciousness.

IX.

When Jacques awoke he was greatly surprised. The ravine, the snow, the forest, the mountain, the gray sky, the freezing wind,—all had disappeared. He looked for his fagot, but could find it nowhere. He had never seen or even heard of this new country; and he was unable to define its substance, to circumscribe its immensity, or appreciate its splendors. The air was balmy, saturated with exquisite perfumes, and it exhaled soft harmonies that made his heart quiver with delight.

He rose. The ground beneath his feet was elastic, and seemed to rise to meet his step, so that walking became restful. A luminous halo hovered about him. Instead of the old torn cloak, he wore a mantle strewn with stars, and it was seamless, like the one for which dice were cast on the heights of Calvary. His hands—his poor little hands, tumefied with chilblains, and which the cold had chapped and creviced,—were now white and soft like the tips of a swan’s wings. Jacques was amazed, but no feeling of fear agitated him. He was calm and felt strangely confident. A great burden seemed to have been lifted from his shoulders; he was as light as the air, and aglow with beatitude.

“Where am I?” he asked; and a voice more harmonious than the whispering of the breeze answered,—

“In my Father’s House, which is the home of the Just.”

Then through a veil of azure and light a great granite crucifix arose before him. It was the crucifix of the Trèves. Grand-Pierre’s cloak, with the rent across it, floated from the shoulders of the Christ. The coarse wool had grown as diaphanous as a cloud, and through it the light radiated as from a sun. The thorns on his brow glittered like carbuncles, and a superhuman beauty lighted his countenance. From fields of space which the sight could now explore came aerial chants. Jacques fell upon his knees and prostrated himself.

The Christ said,—

“Rise, little one; you were moved to pity by the sufferings of your God,—you stripped yourself of your cloak to shield him from the cold, and this is why he has given you his cloak in exchange for yours; for of all the virtues the highest and rarest is charity, which surpasses wisdom and knowledge. Hereafter you will be the host of your God.”

Jacques took a few steps toward the dazzling vision and held out his arms in supplication.

“What do you want?” said the Christ.

The child said, “I want my mother.”

“The angels who carried Mary into Egypt will bring her to you.”

There was a great rustle of wings, and a smile shone on the face of the granite Christ.

Jacques was praying, but his prayer was unlike any that he had ever said before. It was a chant of ecstasy, which rose to his lips in words so beautiful that he experienced a sense of ineffable happiness in listening to himself.

Far away, on the brink of the horizon, pure and clear as crystal, he saw Marguerite borne toward him on billows of white. She was no longer pale, worn, and sad. She was radiant, and glowed with that internal light which is the beauty of the soul, and is alone imperishable. The angels laid her at the foot of the crucifix, and she prostrated herself and adored. When she raised her head there were two souls beside her, and their essences blended in one kiss, in one burst of gratitude. The granite Christ wept.

X.

High in the steeple the bells are conversing. The two younger ones are sullen. “The people in this village are mad. Why can they never be quiet? Were not yesterday’s duties sufficiently tiresome?—midnight Mass, Matins, the Mass of the Aurora, the third Mass, High Mass, Vespers, the Angelus, to say nothing of supplementary chimes. There was no end to it! And now to-day we must begin all over again. They pull us, they shake us,—first the toll for the dead, the funeral service next, then the burial. It is really too much! Why will they never leave us in peace on our frames? Our clappers are weary, and our sides are bruised with the repeated strokes. What can be the matter with these peasants? Here they come to church again in their holiday clothes. Father Monhache wears his most forbidding scowl; his beard bristles fiercely; every now and then he brushes something from his eyes with the back of his hand. His cocked hat has a defiant tilt. The boys had better be on their guard this day. Far down the road there, I see two coffins, one large and one small. They are lifting them on the oxcart; see! But what is that to us, and why are we expected to ring?”

The old bell, full of wisdom and experience, reproved them, saying,—

“Be still, and do not shame me with your ignorance. You have no conception of the dignity of your functions. You have been blessed; you are church-bells. To men you say, ‘Keep vigil over your immortal souls!’ and to God, ‘O Father, have pity on human weakness!’ Instead of being proud of your exalted mission, and meditating upon what you see, you chatter like hand-bells and reason like sleigh-bells. Your bright color and your clear voices need not make you vain, for age will tarnish you and the fatigues of your duty will crack your voices. When years have passed; when you shall have proclaimed church festivals, weddings, births, christenings, and funerals; after having raised the alarms for conflagrations, and rung the tocsin at the invasion of the enemy,—you will no longer complain of your fate; you will begin to comprehend the things of this world, and divine the secrets of the other; you will come to understand how tears on earth can become smiles in heaven.

“So ring gently, gently, without sadness or fear. Let your voices sound like the cooing of doves. A torn cloak in this world may be a mantle of eternal blessedness in the next.”

Maxime Du Camp (1822 – 1894) was an inflentual French writer and friend of the more famous Gustave Flaubert.

Featured: Carrying of the Cross, by Raphael; painted ca. 1516.