“I think a curse should rest upon me – because I love this war. I know it’s smashing and shattering the lives of thousands every moment — and yet — I can’t help it — I enjoy every second of it.”

These words, spoken by Winston Churchill to Violet Asquith on February 22, 1915, suggest a soul dislodged from the fundamental attitude proper to a member of Christian civilization. This attitude towards a war that was wrecking the vestiges of Christendom is not really surprising when we consider Churchill’s well-known membership in the Order of Freemasonry (from 1895) and his also well-known, at least to historians, initiation into the Neo-Pagan Druid Order (from 1908).

The existence and influence of such men as Winston Churchill are the only explanations for the blind inhuman ferocity with which World War I was pursued by the belligerents during the years 1914-1916. The theological, philosophical, and ideological positions of Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty and chief architect of the Gallipoli landings in 1915, simply exemplify the general loss of a Christian consciousness on the part of the leaders of the great Western Powers.

This complete lack of adherence to even the most basic principles of traditional Just War doctrine, was simply incomprehensible to Pope Benedict XV. Why would a war be tolerated which, unlike all others up until that date in European history, seriously threatened to wipe out a vast percentage of the young men on the Continent? Why would not the leaders of Britain and France, chastened and awakened after suffering the loss of 624,000 men in the Battle of the Somme alone, enthusiastically take up consideration of any proposal for a reasonable peace? Why were most of the peace initiatives during the years 1917 and 1918, treated to bemused dismissal and scarcely hidden contempt?

Pope Benedict XV, during the most critical year in contemporary history 1917, found himself confronting men who, like Churchill, appeared to have jettisoned “outdated” humane and moral concerns. That this new non-Christian understanding of conflict and war was not just to characterize the conflict of 1914-1918, is shown by Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s and President Franklin Roosevelt’s drafting and signing of a version of the Morgenthau Plan at the Second Quebec conference of 1944 in which they pledged to turn the heavily urbanized and industrial nation of Germany “into a country primarily agricultural and pastoral in its character.”

What we can say with certainty is that July 1914 inaugurated a generation of political and military slaughtering which was often perpetrated for the sake of “Progress.” It was the dramatic end to an unparalleled era in European history, an era of civil and, on the whole, international peace. It is quite possible that the casualties of all European wars since the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte (1815) did not exceed in number the figure for a single day’s losses in any of the great battles of 1916.

War 1916: Stalemate , U-Boats, and Blockades

December 1916 marked a watershed in World War I. It was a moment when the increasing futility of the military stalemate on the Western Front, induced one side of the conflict – the Central Powers – to seriously consider a negotiated peace. Contrary to a certain simplistic understanding, a desire for a cessation of hostilities and negotiations does not necessarily originate from an experienced position of vulnerability and relative inferiority.

There was a definite long-range prudence and maturity revealed in the Central Powers’ (the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Turkish Ottoman Empire) efforts towards a negotiated peace late in 1916. Not all of it can be attributed to the accession of devote and eminently humane Karl I to the Austrian Imperial Throne and the Hungarian Royal Throne at the death of his great-uncle Franz Josef in November. This “maturity,” which I speak of, can be shown by the fact that these Powers were actually “winning” the war to an extent.

Their military position and advantage appeared for all to see with their knocking the Entente ally, Romania out of the war and conquering Bucharest itself in the beginning of December 1916. Seeking to compensate for the British attempt at a starvation blockade of food and supplies to the Reich, the German military had ordered submarine warfare. This new kind of warfare, which targeted both enemy and neutral shipping, was roundly condemned by Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, the Papal Secretary of State, in the autumn of 1915, speaking of it as “appalling and immoral.”

For the Germans, both during and after the war, this conflict on the open seas was only an attempt to offset the unrestricted blockade imposed by the Entente Powers, which was, also, contrary to established international law. The Great War thus became “as much a war of competing blockades, the surface and the submarine, as of competing armies.”

The German Peace Offensive

The complete stalemate in the Western trenches plus the ruthless warfare at sea, serves as the backdrop of the German Peace Note of December 1916. From the evidence, it appears that Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany believed that everyone (i.e., the leaders of all of Great European Powers) secretly desired peace but that each belligerent was reluctant to be the first to admit it openly. The content of the German Note was simple and clear enough; some commentators called its tone “arrogant.”

Whatever the tone, the Note stated that the war was one of unprecedented fury that threatened to destroy the material and spiritual progress which the 20th century had such a right to be proud of. The Central Empires had amply demonstrated their might and would continue to fight boldly if this peace initiative was ignored. They were, however, desirous of putting an end to the bloodshed. If the Entente Powers agreed to immediate peace negotiations, the Central Powers would guarantee existence, honor, and freedom of development, and would do everything possible to restore lasting peace for the nations then engaged in conflict.

To this German Peace Note, there was no papal response. Benedict XV and Cardinal Gasparri would later, on March 7, 1917, explain, in a letter to the Cardinal-Archbishop of Cologne, that the reason for the coolness of the papal response to the peace gesture on the part of the German Kaiser was that a communication had been received from the British Government, which said that any intervention on the part of the Pope would be “ill-conceived” by Britain and France.

Benedict’s view was that if he offended the Entente Powers at that time, any future efforts would be met with outright antagonism. Moreover, since the Note lacked specific mention of a proposal for the reestablishment of independence for the Kingdom of Belgium, Benedict and Gasparri were not convinced of the usefulness of the initiative. So the Kaiser’s Peace Proposal came to naught. This German peace initiative is usually forgotten by conventional accounts of World War I.

What is also forgotten is the fact that it was only after the failure of this initiative that all restrictions on submarine warfare were lifted. German strategy in this war from the beginning was characterized by a great willingness to gamble. This appeared justified for the Germans at the time on account of the fact that the numbers, both in terms of man power and in terms of production capacity, were heavily skewed against them.

For example, the Entente enjoyed an immense economic superiority over the Central Powers with a combined national income 60% greater. The combined Allies also had 4.5 times as men as great a population as compared to the Germans, Austrians, and the Turks with 28% more men mobilized for the war effort. The policy of the Germans prior to early 1917 and the failure of their peace venture was to sink, without warning, ships believed to be carrying war supplies to Britain.

The German General Staff believed that such a gamble would bring about the defeat of Britain before the United States could make an effective military contribution to the war. This strategy was tried 3 times in 1915, when the Lusitania and Arabic were sunk. It was because of such actions that the German Empire found itself confronted with the outward, rather than just the covert, animosity of the American Republic.

The Pope’s First Moves

Even though British and French disapproval had prevented Pope Benedict XV from taking up the peace proposal made by the German Emperor in 1916 and identical pressure had persuaded him to remain officially aloof, although privately supportive, from the clandestine effort by Blessed Emperor Karl of Austria to establish a back-channel connection to France via his brothers-in-law, Prince Sixtus and Xavier of Bourbon-Parma, both Entente officers, Benedict and his Secretary of State were not inactive in pursuing what they say to be the only “solution” to the conflict, immediate peace and the restoration of the European status quo ante.

In this, they were joined by a whole menagerie of political groups and individuals who were moved by various motives, ideological principles, and, likely, simple human empathy to demand an end to the suicidal European conflict.

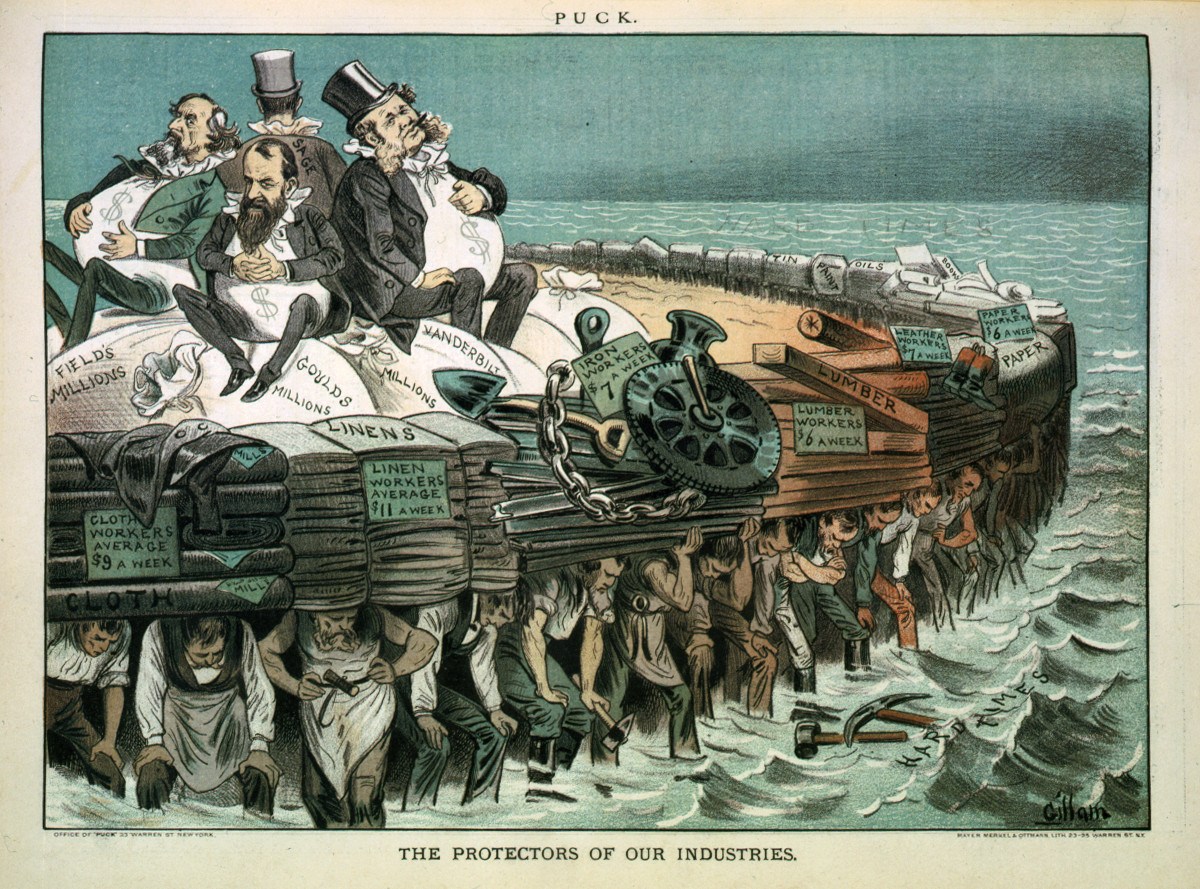

For those on the Left, this war was simply proving to be a capitalist enterprise in which the “military-industrial complex” was benefitting and capitalist nations were attempting to ruthlessly expand their markets. For the traditionalist Right, the war was proving to be just what many had, all along, feared it would be, the catalyst of European social, economic, and political breakdown. This rightist analysis seemed to be conclusively demonstrated by the February Revolution in Russia in 1917 in which the ancient Monarchy was toppled and a provisional parliamentary government put in its place.

It would be this unhistorical, rootless Russian parliamentary regime that the Communist coup d’état would topple in the famous October Revolution in that same year. We can perhaps see the mental make-up of the man when we realize that Woodrow Wilson became ecstatic when he heard the news of the fall of the Russian Imperial Dynasty and then naively stated that, “Now Russia is fit for a league of honor.” The US president, of course, meant that now Russia, having shed its age-old Monarchy, would continue the War as one of the “enlightened” Democratic Powers.

He, also, revealed, in this outburst, that his campaign theme of 1916 “He Kept Us Out of War,” was not to be taken as final. Within a month, the United States, also, would be in this enlightened and “liberating” League. Here, contrary to the implicit beliefs of the Democratists, it was the democratic republican government of Russia in 1917 that wanted to continue fighting the war against the Germans and Austrians. It was the Emperor Nicholas II who was of the view that peace must be concluded quickly for the survival of Russia.

It was for precisely this reason that Lloyd George, the war-enthusiast “Methodist Machiavelli,” who refused to accept the Russian Imperial Family into exile in Britain since the Prime Minister viewed Nicholas as a traitor to the Entente cause. Remember, the Russian general’s phone which ought be “smashed” in order not to receive from the Emperor any order contrary to the provocative mobilization ordered by Minister of War, Sukhomlinov and General Yanushkevitch in August 1914.

What was the immediate cause of a new and final papal effort to halt the slaughter was the efforts of a man who was well-known to the Vatican. The leader of the German Catholic Center Party, Matthias Erzberger was the primary agent of the Imperial Government in its efforts of 1915 to keep Germany’s former ally Italy out of the war.

In this mission, Erzberger had worked closely with the Vatican and had meetings with Pope Benedict himself. Now, Erzberger, in the summer of 1917 after the US declaration of war against Germany but before significant involvement in the European theater of American troops, had been “converted” to a non-annexationist position, that is one which held that Germany should conclude a peace based upon the pre-war borders.

Benedict XV believed that Germany was the key to a successful peace process. Unlike the Entente Powers, Germany and Austria were in control of large areas of occupied territory, most especially Belgium, whose restitution was for the Entente the sine qua non of any settlement.

Benedict began with the premise that only the indication of willingness on Germany’s part to evacuate occupied territory would persuade the Entente to come to the negotiating table. Benedict and Cardinal Gasparri made careful preparations, in the winter and spring of 1917, for what would become their historic peace initiative. In May, in anticipation of the Peace Note, the Pope made personal contact with Blessed Emperor Karl and Empress Zita of Austria.

The Pacelli Factor

If the Germans were the key to peace, Benedict would need a trusted and skilled envoy who could fashion, in conjunction with the Germans, a plausible proposal for peace to present before the Western Allied Powers. That young cleric was Eugenio Pacelli, the priest who would occupy the Papal Throne during the 20th century’s next conflagration – a conflagration, by the way, which was almost the direct result of the failure of the Allies to accept the peace carefully crafted by Archbishop Pacelli. Msgr. Eugenio Pacelli was not a unknown factor at the Vatican in 1917. The Pacelli family had long been involved in Vatican affairs.

The two-year old Eugenio had been brought to the death bed of Blessed Pius IX who is reported to have said, “Teach this little son well so that one day he will serve the Holy See.” He had attended the elite Instituto Capranica, the seminary attended by Benedict himself, and Pacelli, like Benedict, had become a protégé of Cardinal Rampolla during the Cardinal’s years as Secretary of State under Leo XIII.

For those who understand the importance of the Fatima message, it cannot be without significance that Eugenio Pacelli was consecrated as a bishop, and then given the honor of the pallium, on May 13, 1917 (the first day of the Fatima apparitions in Portugal) in a ceremony in the Sistine Chapel by Pope Benedict XV himself. The Pope wanted to give Msgr. Pacelli as much prestige as would be necessary in the royal courts of Germany for this most important peace venture.

If it were not for the eventual contemptuous dismissal of the Pope’s Peace, Archbishop Pacelli’s mission to Germany in this critical year of the war would have been a complete success. After arriving at the royal court of Bavaria (there very much used to be such!), Archbishop Pacelli found the opportunity of making a personal overture, in the name of Benedict XV, to Kaiser Wilhelm himself.

For a man who had been trained to display a complete self-control and dignified comportment, it was indicative of the Emperor’s frustration and emotion when he, with quivering lips, angrily responded to the papal letter which asked him to redouble his efforts to hasten the advent of peace even though it should be at the expense of some of the German objectives.

Wilhelm said that he could not conceal his annoyance at the fact that his own peace efforts of December 1916 had been “snubbed by Benedict XV in so unheard of a manner as not to have merited the courtesy of some reply.” While maintaining complete composure, Archbishop Pacelli stated that certain actions of Germany, for example the deportation of Belgian workers, did not give the Pope reason to attach much confidence to the peace overtures.

According to Walter H. Peters, “The Emperor seems to have taken this argument in good part. He admitted that although the action looked bad at first sight, it had not been against international law. He could not be forced to run the security risk of allowing civilians to remain behind German lines.” Despite the friction and voiced complaints, the meeting with Nuncio Pacelli seems to have made a very positive impression on the Kaiser.

In his autobiography published in 1922, after his abdication and during his exile in Holland, Wilhelm II described his impression of the young Archbishop Pacelli at this critical meeting — critical for what would become Pope Benedict XV’s most important intervention in the World War. The Kaiser describes Pacelli as having, “an aristocratic, likeable, and distinguished appearance, with great intelligence and impeccable manners, the perfect model of a high prelate of the Catholic Church.”

This favorable impression, and the potential within the papal appeal, led the Kaiser, within two weeks, to follow up on the issues discussed at this meeting. On July 12th, the Kaiser arranged a dinner meeting at which the German Chancellor was to present the final draft of a peace resolution which was to go to the German parliament, the Reichstag.

Wilhelm was pleased with the draft since it repeated the statement that the Emperor himself had made in his Address from the Throne of August 4, 1914, in which he stated, “We are not animated by any desire for conquest.” It, also, repeated the statement that Germany had taken up arms only to preserve her independence and to keep intact her possessions.

This was the basic text passed by the Reichstag, with some slight alterations made due to the increasing influence of Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff. On July 14, 1917, the revised peace resolution was laid before the Kaiser, along with a reply that was to be sent to the letter presented by Archbishop Pacelli.

The Kaiser, seeing that the letter was dated August 13 – meaning the Chancellor had intended to significantly delay the German response to the Pope’s letter – said, “Vier Wochen, das ist unhöflich gegen den alten Pontifex!” (“Four weeks, that is discourteous towards the aged Pontiff!). Archbishop Pacelli was delighted with the German response to the Pope’s proposals.

After meeting for two days with the German Chancellor, he returned to Rome on July 25th, with an understanding that the German government was now ready to accept papal peace proposals. Pope Benedict then used this occasion to present his very specific peace proposal to the British representative at the Vatican, Count de Salis.

The Holy Father gave him several sealed envelopes. Each contained a copy of the historical Papal Peace Note of 1917. The British Government was asked to forward the note to France, Italy, and the United States whose governments were not represented at the Vatican. The die was cast.

The Papal Peace Note of August 1917

The Papal Peace Note was very straight forward and apparently non-controversial. It does not seem possible that it could have received such a negative response from several of the warring parties. In the introductory paragraph, the Pope enumerated appeals he had previously made in general terms. He said that the time had come to propose concrete and practical propositions. The task of adjusting them and completing them he would leave to the nations themselves.

The specific proposals were seven in number: 1) Substitution of Moral Force of Right for Law of Material Force; 2) A Simultaneous and Reciprocal Decrease of Armaments; 3) The Establishment of International Courts of Arbitration to Adjudicate Conflicts between Nations; 4) True Freedom and Community of the Seas; 5) Reciprocal Renunciation of War Indemnities; 6) Evacuation and Restoration of All Territories Occupied During the War; 7) Examination in a Conciliatory Spirit of Rival Territorial Claims [e.g., the question of Alsace and Lorraine].

The National Responses to the Papal Peace Proposals were as follows:

Germany: “For a long time His Majesty [Wilhelm II] with profound respect and sincere gratitude had followed the efforts of His Holiness to assuage the sufferings of war…and to hasten the end of the hostilities. The emperor sees in this most recent step of His Holiness a new proof of the noble and humanitarian sentiments, he entertains the lively hope that…success may come to the papal appeal.”

Austria-Hungary: Blessed Emperor Karl I gave an enthusiastic endorsement to the Papal Peace Note.

Bulgaria (one of the Central Powers): King Ferdinand replied to the Peace Note on September 26, 1917, in terms of reverence and loyalty.

Ottoman Empire: The Sultan of the Turkish Moslem Empire, Mehmed V, in an autographed letter on September 30, said that he was “deeply touched by the lofty thoughts of His Holiness.”

France: No direct response to the Pope’s Note. Merely a sharply worded statement issued by Foreign Minister Ribot to the British Government indicating that they (the French) did not intend to have an official statement in writing communicated to the Holy See. The British Government was asked to, “discourage any further attempt on the part of the Papal Secretary of State in the direction of an official intervention between the belligerents.”

Italy: In an address to the Italian Senate, Baron Sydney Sonnino, Italian Foreign Minister, stated that the Note was nothing but the work of Germany and that the proposals were utterly impracticable.

Britain: Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Minister (famous for the Balfour Declaration), responded in a very non-committal way: “His Majesty’s Government, not having as yet been able to take the opinion of their Allies, cannot say whether it would serve any useful purpose to offer a reply or, if so, what form such a reply should take. Although the Central Powers have admitted their guilt in regard to Belgium, they have never definitely intimated that they intend either to restore her to her former state or entire independence or to make good the damage she has suffered at their hands.”

Papal Peace Meets American Democratic Messianism

Wilson’s Intervention “What does he want to butt in for?” Here we have the unique first response from President Woodrow Wilson upon the presentation of the Pope’s Peace Note to him at the White House in August of 1917. The relations between the Roman Pontiff and the Presbyterian minister’s son from the Shenandoah Valley who sat in the White House had always been a bit tense. Contrary to pacific statements and neutralist campaign slogans, at the Vatican it was always understood that the United States, under its Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, was not actually a neutral and impartial player in the Great European Conflict.

The United States was clearly helping the Entente and for what the Vatican believed were selfish reasons. It was held that the US was committed to France and Britain because of economic ties. Benedict XV, in particular, deplored the United States’ arms trade with France and Britain, especially when it was carried on the passenger vessels, thus providing a causa belli against Germany. In light of this, it was as early as April of 1915, a full two years before official US involvement in the war, that Benedict called upon the United States to enforce an arms embargo against both sides.

This, of course, was never done. Included in this analysis of the American attitude towards the war, must have been a recognition that the tragedy of the sinking of the British liner RMS Lusitania, had been engineered to ease the United States’ entry into the war. This joint British-American operation had been executed at the expense of 1,198 human lives. Among the dead were 128 Americans.

On April 22, 1915, a week and a half before the liner departed, an announcement was issued by the German Embassy in Washington which warned passengers that Germany was in a state of war with Great Britain and, therefore, all ships sailing under her or her allies’ flag were subject to attack and that passengers were, therefore, traveling at their own risk. For some unknown reason, newspapers did not publish the warning until the day of departure. Some 8 miles off the coast of Ireland, a German U-20 submarine fired one torpedo at the liner. After the torpedo hit there was a second explosion. Within 18 minutes the ship sank, with the passengers in general panic.

As the Germans insisted at the time, and a 1960 investigation by an American John Light confirmed, the ship had been filled to the gills with contraband munitions making it a legitimate target according to international law. Included in this stock, were some 4,200,000 rounds of Remington .303 rifle cartridges.

This was also confirmed by later British documents that came to light along with the ship’s manifest, which had been given to Woodrow Wilson and was only released at the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Allen Welsh Dulles, brother of the future Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, knew well of the engineering of the tragedy.

It would still be some 2 years until the United States officially entered the conflict. Perhaps, this was to get past the presidential election of 1916 in which Wilson barely, due to a narrow margin in the State of California, beat his Republican opponent Charles Evans Hughes, on a platform of neutralism and peace, “He Kept US Out of War!” It was immediately after the election that Wilson momentarily acted as the neutral observer of the horror of the European conflict.

On December 20, 1916, when the peace efforts of the Central Powers were well underway, the United States issued an appeal that included the statement, “The President is not proposing peace; he is not even offering mediation. He is merely proposing that soundings be taken in order that we may learn, the neutral nations [here he apparently includes the United States] with belligerents, how near the haven of peace may be for which all mankind longs with an intense and increasing longing.”

When, only 4 months after the “peace appeal,” Wilson broke off relations with the German Empire, clearly in preparation for a declaration of war, the Holy See attempted to heal the breach — seemingly due to the impression at the Vatican that the United States was merely reacting to individual acts of the German military and political authorities. Therefore, we can understand the shock experienced by the Pope when he heard the news of the United States’ declaration of war against the Central Powers in April of 1917.

This was understood by Pope Benedict XV to be an unmitigated disaster. His Holiness understood, with utmost clarity, that American intervention would extend the time of the conflict since there would be absolutely no reason for the Entente Powers to consider a cease-fire or armistice.

Even though it is difficult get into the mind of another man, particularly if that man is the Vicar of Christ, it appears that the Pope did not fully appreciate the extent to which the Presbyterian President viewed the war in Europe as a “crusade” for equality and democracy.

This is the only explanation for the blind-siding of the Pope in this case and in Wilson’s final and conclusive rejection of Benedict’s great peace initiative of August 1, 1917. Wilson believed that this war was one of the “enlightened” Powers of parliamentary and democratic regimes, recently stripped of the “embarrassment” of Nicholas II, against the dark “holdovers.”

Wilson’s throwing of America’s sword onto the scale of the Entente Powers, changed the conflict from a fratricidal conflict over Alsace-Lorraine and Flanders, to a global crusade against Monarchy and, what would show itself after the war, against Papal influence in the political affairs of the world. In other words, against historical Christendom.

It would not be stretching it to say that with the rejection of Pope Benedict’s Peace Note of August 1917, Woodrow Wilson became the grave-digger of Christendom. What might not have happened had not the war continued to its tragic end – the downfall of the Russian, Austrian, and Prussia monarchies? Can we venture Communist Russia, Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, World War II, the Cold War, Mutually Assured Destruction doctrine, Korea, Red China, Vietnam, the Social Revolution of the 1960s, and perhaps, Vatican II?

What we can be certain of is that these things would not have happened as they did if Wilson had not, “butted in.” It is only with this anti-monarchical and anti-papal attitude in mind that we can understand the patronizing and cool response of Woodrow Wilson, through his Secretary of State Robert Lansing, to the Papal Peace Note.

Robert Lansing prepared the world for Wilson’s fatal response by his own articulation of the fundamental principle of American foreign policy, both then and now: “No people can desire war, particularly an aggressive war. If the people can exercise their will, they will remain at peace. If a nation possesses democratic institutions, the popular will will be executed. Consequently, if the principle of democracy prevails in a nation, it can be counted upon to preserve peace and oppose wars…If this view is correct, then the effort should be made to make democracy universal.”

In a letter dated August 27, 1917, Robert Lansing, speaking for President Wilson, responded to the Pope’s Peace Note by stating the following, “No part of this program can be carried out. The object of this war is to deliver the free peoples of the world from the menace and the actual power of a vast military establishment controlled by an irresponsible government which having planned secretly to dominate the world, proceeded to carry the plan out. This power is not the German people. It is the ruthless master of the German people. It is no business of ours how that great people came under its control. But it is out business to see that the history of the rest of the world is no longer left to its handling…. They desire no reprisal upon the German people who have themselves suffered all things in this war which they did not choose. They believe that peace should rest upon the rights of the people, not the rights of governments….The word of an ambitious and intriguing government on the one hand and a group of free peoples on the other….We cannot take the word of the present rulers of Germany as a guaranty of anything that is to endure, unless explicitly supported by such conclusive evidence of the will and purpose of the German people themselves.”

Pope Benedict’s attempt to stop the war which would kill 9.4 million and open the Age of Totalitarianism ended with this rejection. The Entente Powers allowed Wilson to speak for them. As the great biographer of Pope Benedict XV, Walter Peters, states, “Wilson could not endorse Benedict’s plan because the prime premises of the two men differed so radically. Wilson was motivated by an urge to punish. In Wilson’s opinion, it was absolutely necessary that the ruling dynasties of Germany and Austria be forced to abdicate.”

Pope Benedict XV told one of his friends that it was the bitterest moment of his life when he heard of the rejection of the Note by Woodrow Wilson.

1918: Why The War Ended

When considering the failure of the peace initiatives of the Holy Father and others, we can understand why the war did not end. But why did it end? Did the Germans lose? Yes and No. According to the most recent historians of the period, it was the collapse of German morale on the Western Front, which brought about the defeat of Germany and Austria in the Great War.

Even after the failure of Ludendorff’s famous Michael Offensive in the Spring of 1918, the Germans and Austrians were still killing the Allies at a faster rate than they themselves were getting killed by the British and French (Note, the US Army was on the Western Front in substantial number only in the Autumn of 1918).

In the last 3 months of the fighting, for example, 63,500 British soldiers were killed, while 28,000 Germans were killed. It was not the Germans who elected to continue fighting who brought about the collapse of the Central Powers, it was those Germans who elected to surrender – or desert, shirk or strike – who ended the war.

This becomes clear, even by looking at the basic casualty count for the entire war 1914-1918: 9.4 million total casualties, 4 million dead from the Central Powers and 5.4 million dead from the Entente.

Most of the surrendering occurred at the end of the war, from August 1918 when General Ludendorff first started asking for an armistice and the second week of November when Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and went into exile in Holland. Probably the greatest chance Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy had of winning the struggle, was if Emperor Nicholas II had accepted, as early as 1915, a separate peace offer from the Germans and Austrians.

The Central Monarchies might well have won the war early and Russia would almost certainly have avoided Communism. When the Russians spurned these advances, the Germans went on to inflict total defeat on them, making the triumph of Communism possible. In 1919, the Versailles Conference met without the attendance of a representative of the Holy See.

Just as the Versailles Treaty was the first one since the early years of Christendom not to invoke the Holy Trinity, the Father of Christendom would have no place at the table which would profoundly rearrange the map of Europe. As Emperor Franz Josef stated at the end of his life, “Europe is dead.” It was the tragic fate of Pope Benedict XV, the man who loved Europe most, to weep at her tomb.

Peter Chojnowski is a professor, writer and currently teaches at Immaculate Conception Academy in Post Falls, Idaho.

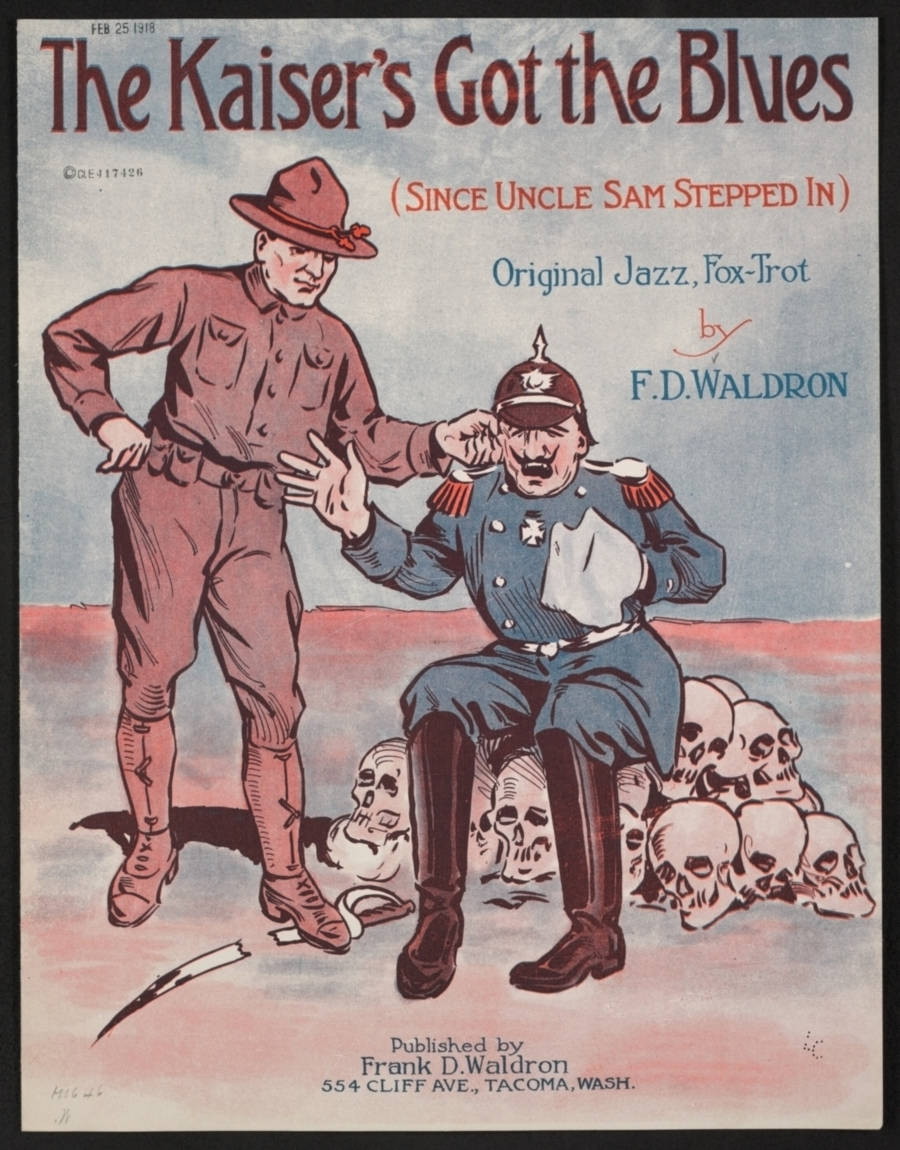

The image shows, “Kaiser’s Got The Blues,” cover or sheet music from 1918.