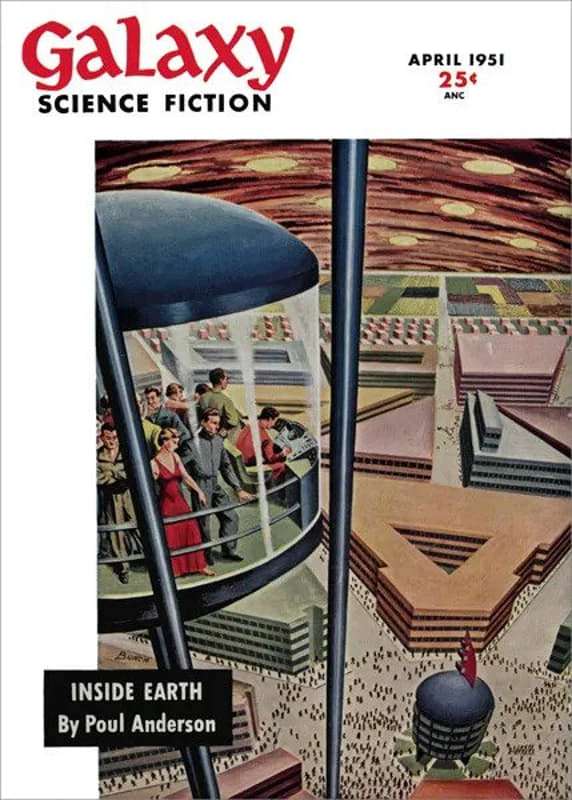

This story first appeared in the April 1951 issue of the science fiction magazine, Galaxy.

In the country of the blind, the one-eyed man, of course, is king. But how a live wire, a smart businessman, in a civilization of 100% pure chumps?

Some things had not changed. A potter’s wheel was still a potter’s wheel and clay was still clay. Efim Hawkins had built his shop near Goose Lake, which had a narrow band of good fat clay and a narrow beach of white sand. He fired three bottle-nosed kilns with willow charcoal from the wood lot. The wood lot was also useful for long walks while the kilns were cooling; if he let himself stay within sight of them, he would open them prematurely, impatient to see how some new shape or glaze had come through the fire, and—ping!—the new shape or glaze would be good for nothing but the shard pile back of his slip tanks.

A business conference was in full swing in his shop, a modest cube of brick, tile-roofed, as the Chicago- Los Angeles “rocket” thundered overhead—very noisy, very swept-back, very fiery jets, shaped as sleekly swift-looking as an airborne barracuda.

The buyer from Marshall Fields was turning over a black-glazed one liter carafe, nodding approval with his massive, handsome head. “This is real pretty,” he told Hawkins and his own secretary, Gomez-Laplace. “This has got lots of what ya call real est’etic principles. Yeah, it is real pretty.”

“How much?” the secretary asked the potter.

“Seven-fifty each in dozen lots,” said Hawkins. “I ran up fifteen dozen last month.”

“They are real est’etic,” repeated the buyer from Fields. “I will take them all.”

“I don’t think we can do that, doctor,” said the secretary. “They’d cost us $1,350. That would leave only $532 in our quarter’s budget. And we still have to run down to East Liverpool to pick up some cheap dinner sets.”

“Dinner sets?” asked the buyer, his big face full of wonder.

“Dinner sets. The department’s been out of them for two months now. Mr. Garvy-Seabright got pretty nasty about it yesterday. Remember?”

“Garvy-Seabright, that meat-headed bluenose,” the buyer said contemptuously. “He don’t know nothin’ about est’etics. Why for don’t he lemme run my own department?” His eye fell on a stray copy of Whambozambo Comix and he sat down with it. An occasional deep chuckle or grunt of surprise escaped him as he turned the pages.

Uninterrupted, the potter and the buyer’s secretary quickly closed a deal for two dozen of the liter carafes. ”I wish we could take more,” said the secretary, “but you heard what I told him. We’ve had to turn away customers for ordinary dinnerware because he shot the last quarter’s budget on some Mexican piggy banks some equally enthusiastic importer stuck him with. The fifth floor is packed solid with them.”

“I’ll bet they look mighty est’etic.”

“They’re painted with purple cacti.”

The potter shuddered and caressed the glaze of the sample carafe.

The buyer looked up and rumbled, “Ain’t you dummies through yakkin’ yet? What good’s a seckertary for if’n he don’t take the burden of de-tail off’n my back, harh?”

“We’re all through, doctor. Are you ready to go?”

The buyer grunted peevishly, dropped Whambozambo Comix on the floor and led the way out of the building and down the log corduroy road to the highway. His car was waiting on the concrete. It was, like all contemporary cars, too low-slung to get over the logs. He climbed down into the car and started the motor with a tremendous sparkle and roar.

“Gomez-Laplace,” called out the potter under cover of the noise, “did anything come of the radiation program they were working on the last time I was on duty at the Pole?”

“The same old fallacy,” said the secretary gloomily. “It stopped us on mutation, it stopped us on culling, it stopped us on segregation, and now it’s stopped us on hypnosis.”

“Well, I’m scheduled back to the grind in nine days. Time for another firing right now. I’ve got a new luster to try . . .”

“I’ll miss you. I shall be ‘vacationing’—running the drafting room of the New Century Engineering Corporation in Denver. They’re going to put up a two hundred-story office building, and naturally somebody’s got to be on hand.”

“Naturally,” said Hawkins with a sour smile.

There was an ear-piercingly sweet blast as the buyer leaned on the horn button. Also, a yard-tall jet of what looked like flame spurted up from the car’s radiator cap; the car’s power plant was a gas turbine, and had no radiator.

“I’m coming, doctor,” said the secretary dispiritedly. He climbed down into the car and it whooshed off with much flame and noise.

The potter, depressed, wandered back up the corduroy road and contemplated his cooling kilns. The rustling wind in the boughs was obscuring the creak and mutter of the shrinking refractory brick. Hawkins wondered about the number two kiln—a reduction fire on a load of lusterware mugs. Had the clay chinking excluded the air? Had it been a properly smoky blaze? Would it do any harm if he just took one close—?

Common sense took Hawkins by the scruff of the neck and yanked him over to the tool shed. He got out his pick and resolutely set off on a prospecting jaunt to a hummocky field that might yield some oxides. He was especially low on coppers.

The long walk left him sweating hard, with his lust for a peek into the kiln quiet in his breast. He swung his pick almost at random into one of the hummocks; it clanged on a stone which he excavated. A largely obliterated inscription said:

ERSITY OF CHIC

OGICAL LABO

ELOVED MEMORY OF

KILLED IN ACT

The potter swore mildly. He had hoped the field would turn out to be a cemetery, preferably a once- fashionable cemetery full of once-massive bronze caskets moldered into oxides of tin and copper.

Well, hell, maybe there was some around anyway.

He headed lackadaisically for the second largest hillock and sliced into it with his pick. There was a stone to undercut and topple into a trench, and then the potter was very glad he’d stuck at it. His nostrils were filled with the bitter smell and the dirt was tinged with the exciting blue of copper salts. The pick went clang!

Hawkins, puffing, pried up a stainless steel plate that was quite badly stained and was also marked with incised letters. It seemed to have pulled loose from rotting bronze; there were rivets on the back that brought up flakes of green patina. The potter wiped off the surface dirt with his sleeve, turned it to catch the sunlight obliquely and read:

“HONEST JOHN BARLOW

“Honest John,” famed in university annals, represents a challenge which medical science has not yet answered: revival of a human being accidentally thrown into a state of suspended animation.

In 1988 Mr. Barlow, a leading Evanston real estate dealer, visited his dentist for treatment of an impacted wisdom tooth. His dentist requested and received permission to use the experimental anesthetic Cycloparadimetbanol-B-7, developed at the University.

After administration of the anesthetic, the dentist resorted to his drill. By freakish mischance, a short circuit in his machine delivered 220 volts of 60-cycle current into the patient. (In a damage suit instituted by Mrs. Barlow against the dentist, the University and the makers of the drill, a jury found for the defendants.) Mr. Barlow never got up from the dentist’s chair and was assumed to have died of poisoning, electrocution or both.

Morticians preparing him for embalming discovered, however, that their subject was—though certainly not living—just as certainly not dead. The University was notified and a series of exhaustive tests was begun, including attempts to duplicate the trance state on volunteers. After a bad run of seven cases which ended fatally, the attempts were abandoned.

Honest John was long an exhibit at the University museum, and livened many a football game as mascot of the University’s Blue Crushers. The bounds of taste were overstepped, however, when a pledge to Sigma Delta Chi was ordered in ’03 to “kidnap” Honest John from his loosely guarded glass museum case and introduce him into the Rachel Swanson Memorial Girls’ Gymnasium shower room.

On May 22nd, 2003, the University Board of Regents issued the following order: “By unanimous vote, it is directed that the remains of Honest John Barlow be removed from the University museum and conveyed to the University’s Lieutenant James Scott III Memorial Biological Laboratories and there be securely locked in a specially prepared vault. It is further directed that all possible measures for the preservation of these remains be taken by the Laboratory administration and that access to these remains be denied to all persons except qualified scholars authorized in writing by the Board. The Board reluctantly takes this action in view of recent notices and photographs in the nation’s press which, to say the least, reflect but small credit upon the University.”

It was far from his field, but Hawkins understood what had happened—an early and accidental blundering onto the bare bones of the Levantman shock anesthesia, which had since been replaced by other methods. To bring subjects out of Levantman shock, you let them have a squirt of simple saline in the trigeminal nerve. Interesting. And now about that bronze—

He heaved the pick into the rotting green salts, expecting no resistence, and almost fractured his wrist. Something down there was solid. He began to flake off the oxides.

A half hour of work brought him down to phosphor bronze, a huge casting of the almost incorruptible metal. It had weakened structurally over the centuries; he could fit the point of his pick under a corroded boss and pry off great creaking and grumbling striae of the stuff.

Hawkins wished he had an archeologist with him, but didn’t dream of returning to his shop and calling one to take over the find. He was an all-around man: by choice and in his free time, an artist in clay and glaze; by necessity, an automotive, electronics and atomic engineer who could also swing a project in traffic control, individual and group psychology, architecture or tool design. He didn’t yell for a specialist every time something out of his line came up; there were so few with so much to do…

He trenched around his find, discovering that it was a great brick-shaped bronze mass with an excitingly hollow sound. A long strip of moldering metal from one of the long vertical faces pulled away, exposing red rust that went whoosh and was sucked into the interior of the mass.

It had been de-aired, thought Hawkins, and there must have been an inner jacket of glass which had crystalized through the centuries and quietly crumbled at the first clang of his pick. He didn’t know what a vacuum would do to a subject of Levantman shock, but he had hopes, nor did he quite understand what a real estate dealer was, but it might have something to do with pottery. And anything might have a bearing on Topic Number One.

He flung his pick out of the trench, climbed out and set off at a dog-trot for his shop. A little rummaging turned up a hypo and there was a plasticontainer of salt in the kitchen.

Back at his dig, he chipped for another half hour to expose the juncture of lid and body. The hinges were hopeless; he smashed them off.

Hawkins extended the telescopic handle of the pick for the best leverage, fitted its point into a deep pit, set its built-in fulcrum, and heaved. Five more heaves and he could see, inside the vault, what looked like a dusty marble statue. Ten more and he could see that it was the naked body of Honest John Barlow, Evanston real estate dealer, uncorrupted by time.

The potter found the apex of the trigeminal nerve with his needle’s point and gave him 60 cc.

In an hour Barlow’s chest began to pump.

In another hour, he rasped, “Did it work?”

“Did it!” muttered Hawkins. Barlow opened his eyes and stirred, looked down, turned his hands before his eyes—

“I’ll sue!” he screamed. “My clothes! My fingernails!” A horrid suspicion came over his face and he clapped his hands to his hairless scalp. “My hair!” he wailed. “I’ll sue you for every penny you’ve got! That release won’t mean a damned thing in court—I didn’t sign away my hair and clothes and fingernails!”

“They’ll grow back,” said Hawkins casually. “Also your epidermis. Those parts of you weren’t alive, you know, so they weren’t preserved like the rest of you. I’m afraid the clothes are gone, though.”

“What is this— the University hospital?” demanded Barlow. “I want a phone. No, you phone. Tell my wife I’m all right and tell Sam Immerman—he’s my lawyer—to get over here right away. Greenleaf 7-4022. Ow!” He had tried to sit up, and a portion of his pink skin rubbed against the inner surface of the casket, which was powdered by the ancient crystalized glass. “What the hell did you guys do, boil me alive? Oh, you’re going to pay for this!”

“You’re all right,” said Hawkins, wishing now he had a reference book to clear up several obscure terms. “Your epidermis will start growing immediately. You’re not in the hospital. Look here.”

He handed Barlow the stainless steel plate that had labeled the casket. After a suspicious glance, the man started to read. Finishing, he laid the plate carefully on the edge of the vault and was silent for a spell.

“Poor Verna,” he said at last. “It doesn’t say whether she was stuck with the court costs. Do you happen to know—”

“No,” said the potter. “All I know is what was on the plate, and how to revive you. The dentist accidentally gave you a dose of what we call Levantman shock anesthesia. We haven’t used it for centuries; it was powerful, but too dangerous.”

“Centuries . . .” brooded the man. “Centuries . . . I’ll bet Sam swindled her out of her eyeteeth. Poor Verna. How long ago was it? What year is this?”

Hawkins shrugged. “We call it 7-B-936. That’s no help to you. It takes a long time for these metals to oxidize.”

“Like that movie,” Barlow muttered. “Who would have thought it? Poor Verna!” He blubbered and sniffled, reminding Hawkins powerfully of the fact that he had been found under a flat rock.

Almost angrily, the potter demanded, “How many children did you have?”

“None yet,” sniffed Barlow. “My first wife didn’t want them. But Verna wants one—wanted one—but we’re going to wait until—we were going to wait until— ”

“Of course,” said the potter, feeling a savage desire to tell him off, blast him to hell and gone for his work. But he choked it down. There was The Problem to think of; there was always The Problem to think of, and this poor blubberer might unexpectedly supply a clue. Hawkins would have to pass him on.

“Come along,” Hawkins said. “My time is short.”

Barlow looked up, outraged. “How can you be so unfeeling? I’m a human being like—”

The Los Angeles-Chicago “rocket” ‘thundered overhead and Barlow broke off in mid-complaint. “Beautiful!” he breathed, following it with his eyes. “Beautiful!”

He climbed out of the vault, too interested to be pained by its roughness against his infantile skin. “After all,” he said briskly, “this should have its sunny side. I never was much for reading, but this is just like one of those stories. And I ought to make some money out of it, shouldn’t I?” He gave Hawkins a shrewd glance.

“You want money?” asked the potter. “Here.” He handed over a fistful of change and bills. “You’d better put my shoes on. It’ll be about a quarter-mile. Oh, and you’re—uh, modest?—yes, that was the word. Here.” Hawkins gave him his pants, but Barlow was excitedly counting the money.

“Eighty-five, eighty-six—and it’s dollars, too ! I thought it’d be credits or whatever they call them. ‘E Pluribus Unum’ and ’Liberty’—just different faces. Say, is there a catch to this? Are these real, genuine. honest twenty-two-cent dollars like we had or just wallpaper?”

“They’re quite all right, I assure you,” said the potter. “I wish you’d come along. I’m in a ‘hurry.”

The man babbled as they stumped toward the shop. “Where are we going—The Council of Scientists, the World Coordinator or something. like that?”

“Who? Oh, no. We call them ‘President’ and ‘Congress.’ No, that wouldn’t do any good at all. I’m just taking you to see some people.”

“I ought to make plenty out of this. Plenty! I could write books. Get some smart young fellow to put it into words for me and I’ll bet I could turn out a best-seller. What’s the setup on things like that?”

“It’s about like that. Smart young fellows. But there aren’t any best-sellers any more. People don’t read much nowadays. We’ll find something equally profitable for you to do.”

Back in the shop, Hawkins gave Barlow a suit of clothes, deposited him in the waiting room and called Central in Chicago. “Take him away,” he pleaded. “I have time for one more firing and he blathers and blathers. I haven’t told him anything. Perhaps we should just turn him loose and let him find his own level, but there’s a chance—”

“The Problem,” agreed Central. “Yes, there’s a chance.”

The potter delighted Barlow by making him a cup of coffee with a cube that not only dissolved in cold water but heated the water to boiling point. Killing time, Hawkins chatted about the “rocket” Barlow had admired, and had to haul himself up short; he had almost told the real estate man what its top speed really was—almost, indeed, revealed that it was not a rocket.

He regretted, too, that he had so casually handed Barlow a couple of hundred dollars. The man seemed obsessed with fear that they were worthless since Hawkins refused to take a note or I.O.U. or even a definite promise of repayment. But Hawkins couldn’t go into details, and was very glad when a stranger arrived from Central.

“Tinny-Peete, from Algeciras,” the stranger told him swiftly as the two of them met at the door. “Psychist for Poprob. Polasigned special overtake Barlow.”

“Thank Heaven,” said Hawkins. “Barlow,” he told the man from the past, “this is Tinny-Peete. He’s going to take care of you and help you make lots of money.”

The psychist stayed for a cup of the coffee whose preparation had delighted Barlow, and then conducted the real estate man down the corduroy road to his car, leaving the potter to speculate on whether he could at last crack his kilns.

Hawkins, abruptly dismissing Barlow and the Problem, happily picked the chinking from around the door of the number two kiln, prying it open a trifle. A blast of heat and the heady, smoky scent of the reduction fire delighted him. He peered and saw a corner of a shelf glowing cherry-red, becoming obscured by wavering black areas as it lost heat through the opened door. He slipped a charred wood paddle under a mug on the shelf and pulled it out as a sample, the hairs on the back of his hand curling and scorching. The mug crackled and pinged and Hawkins sighed happily.

The bismuth resinate luster had fired to perfection, a haunting film of silvery-black metal with strange bluish lights in it as it turned before the eyes, and the Problem of Population seemed very far away to Hawkins then.

Barlow and Tinny-Peete arrived at the concrete highway where the psychist’s car was parked in a safety bay.

“What—a—boat!” gasped the man from the past.

“Boat? No, that’s my car.”

Barlow surveyed it with awe. Swept-back lines, deep-drawn compound curves, kilograms of chrome. He ran his hands futilely over the door—or was it the door?—in a futile search for a handle, and asked respectfully, “How fast does if go?”

The psychist gave him a keen look and said slowly, “Two hundred and fifty. You can tell by the speedometer.”

“Wow! My old Chevvy could hit a hundred on a straightaway, but you’re out of my class, mister!”

Tinny-Peete somehow got a huge, low door open and Barlow descended three steps into immense cushions, floundering over to the right. He was too fascinated to pay serious attention to his flayed dermis. The dashboard was a lovely wilderness of dials, plugs, indicators, lights, scales and switches.

The psychist climbed down into the driver’s seat and did something with his feet. The motor started like lighting a blowtorch as big as a silo. Wallowing around in the cushions, Barlow saw through a rear-view mirror a tremendous exhaust filled with brilliant white sparkles.

“Do you like it?” yelled the psychist.

“It’s terrific!” Barlow yelled back. “It’s—”

He was shut up as the car pulled out from the bay into the road with a great voo-ooo-ooom! A gale roared past Barlow’s head, though the windows seemed to be closed; the impression of speed was terrific. He located the speedometer on the dashboard and saw it climb past 90, 100, 150, 200.

“Fast enough for me,” yelled the psychist, noting that Barlow’s face fell in response. “Radio?”

He passed over a surprisingly light object like a football helmet, with no trailing wires, and pointed to a row of buttons. Barlow put on the helmet, glad to have the roar of air stilled, and pushed a push- button. It lit up satisfyingly and Barlow settled back even farther for a sample of the brave new world’s super-modern taste in ingenious entertainment.

“TAKE IT AND STICK IT!” a voice roared in his ears.

He snatched off the helmet and gave the psychist an injured look. Tinny-Peete grinned and turned a dial associated with the pushbutton layout. The man from the past donned the helmet again and found the voice had lowered to normal.

“The show of shows! The super-show! The super-duper show! The quiz of quizzes! Take it and stick it!”

There were shrieks of laughter in the background.

“Here we got the contestants all ready to go. You know how we work it. I hand a contestant a triangle-shaped cutout and like that down the line. Now we got these here boards, they got cut-out places the same shape as the triangles and things, only they’re all different shapes, and the first contestant that sticks the cutouts into the board, he wins.

“Now I’m gonna innaview the first contestant. Right here, honey. What’s your name?’’

“Name? Uh—”

“Hoddaya like that, folks? She don’t remember her name! Hah? Would you buy that for a quarter?” The question was spoken with arch significance, and the audience shrieked, howled and whistled its appreciation.

It was dull listening when you didn’t know the punch lines and catch lines. Barlow pushed another button, with his free hand ready at the volume control.

” — latest from Washington. It’s about Senator Hull-Mendoza. He is still attacking the Bureau of Fisheries. The North California Syndicalist says he got affidavits that John Kingsley-Schultz is a bluenose from way back. He didn’t publistat the affydavits, but he says they say that Kingsley-Schultz was saw at bluenose meetings in Oregon State College and later at Florida University. Kingsley-Schultz says he gotta confess he did major in fly-casting at Oregon and got his Ph.D. in game-fish at Florida.

“And here is a quote from Kingsley-Schultz: ‘Hull-Mendoza don’t know what he’s talking about. He should drop dead.’ Unquote. Hull-Mendoza says he won’t publistat the affydavits to pertect his sources. He says they was sworn by three former employes of the Bureau which was fired for in-com-petence and in-com-pat-ibility by Kingsley-Schultz.

“Elsewhere they was the usual run of traffic accidents. A three-way pileup of cars on Route 66 going outta Chicago took twelve lives. The Chicago-Los Angeles morning rocket crashed and exploded in the Mo-have—Mo-jawy—what-ever-you-call-it Desert. All the 94 people aboard got killed. A Civil Aeronautics Authority investigator on the scene says that the pilot was buzzing herds of sheep and didn’t pull out in time.

“Hey! Here’s a hot one from New York! A Diesel tug run wild in the harbor while the crew was below and shoved in the port bow of the luck-shury liner S. S. Placentia. It says the ship filled and sank taking the lives of an es-ti-mated 180 passengers and 50 crew members. Six divers was sent down to study the wreckage, but they died, too, when their suits turned out to be fulla little holes.

“And here is a bulletin I just got from Denver. It seems—”

Barlow took off the headset uncomprehendingly. “He seemed so callous,” he yelled at the driver. “I was listening to a newscast — ”

Tinny-Peete shook his head and pointed at his ears. The roar of air was deafening. Barlow frowned baffledly and stared out of the window.

A glowing sign said:

MOOGS!

WOULD YOU BUY IT

FOR A QUARTER?

He didn’t know what Moogs was or were; the illustration showed an incredibly proportioned girl, 99.9 per cent naked, writhing passionately in animated full color.

The roadside jingle was still with him, but with a new feature. Radar or something spotted the car and alerted the lines of the jingle. Each in turn sped along a roadside track, even with the car, so it could be read before the next line was alerted.

IF THERE’S A GIRL

YOU WANT TO GET

DEFLOCCULIZE

UNROMANTIC SWEAT.

“A*R*M*P*I*T*T*O*”

Another animated job, in two panels, the familiar “Before and After.” The first said, “Just Any Cigar?” and was illustrated with a two-person domestic tragedy of a wife holding her nose while her coarse and red-faced husband puffed a slimy-looking rope. The second panel glowed, “Or a VUELTA ABAJO?” and was illustrated with—

Barlow blushed and looked at his feet until they had passed the sign.

“Coming into Chicago!” bawled Tinny-Peete.

Other cars were showing up, all of them dreamboats.

Watching them, Barlow began to wonder if he knew what a kilometer was, exactly. They seemed to be traveling so slowly, if you ignored the roaring air past your ears and didn’t let the speedy lines of the dreamboats fool you. He would have sworn they were really crawling along at twenty-five, with occasional spurts up to thirty. How much was a kilometer, anyway?

The city loomed ahead, and it was just what it ought to be: towering skyscrapers, overhead ramps, landing platforms for helicopters—

He clutched at the cushions. Those two ‘copters. They were going to—they were going to—they—

He didn’t see what happened because their apparent collision courses took them behind a giant building.

Screamingly sweet blasts of sound surrounded them as they stopped for a red light. “What the hell is going on here?” said Barlow in a shrill, frightened voice, because the braking time was just about zero, he wasn’t hurled against the dashboard. “Who’s kidding who?”

“Why, what’s the matter?” demanded the driver.

The light changed to green and he started the pickup. Barlow stiffened as he realized that the rush of air past his ears began just a brief, unreal split-second before the car was actually moving. He grabbed for the door handle on his side.

The city grew on them slowly: scattered buildings, denser buildings, taller buildings, and a red light ahead. The car rolled to a stop in zero braking time, the rush of air cut off an instant after it stopped, and Barlow was out of the car and running frenziedly down a sidewalk one instant after that.

They’ll track me down, he thought, panting. It’s a secret police thing. They’ll get you— mind-reading machines, television eyes everywhere, afraid you’ll tell their slaves about freedom and stuff. They don’t let anybody cross them, like that story I once read.

Winded, he slowed to a walk and congratulated himself that he had guts enough not to turn around. That was what they always watched for. Walking, he was just another business-suited back among hundreds. He would be safe, he would be safe—

A hand tumbled from a large, coarse, handsome face thrust close to his: “Wassamatta bumpinninna people likeya owna sidewalk gotta miner slamya inna mushya bassar!” It was neither the mad potter nor the mad driver.

“Excuse me,” said Barlow. “What did you say?”

“Oh, yeah?” yelled the stranger dangerously, and waited for an answer.

Barlow, with the feeling that he had somehow been suckered into the short end of an intricate land- title deal, heard himself reply belligerently, “Yeah!”

The stranger let go of his shoulder and snarled, “Oh, yeah?” “Yeah!” said Barlow, yanking his jacket back into shape.

“Aaah!” snarled the stranger with more contempt and disgust than ferocity. He added an obscenity current in Barlow’s time, a standard but physiologically impossible directive, and strutted off hulking his shoulders and balling his fists.

Barlow walked on, trembling. Evidently he had handled it well enough. He stopped at a red light while the long, low dream-boats roared before him and pedestrians in the sidewalk flow with him threaded their ways through the stream of cars. Brakes screamed, fenders clanged and dented, hoarse cries flew back and forth between drivers and walkers. He leaped backward frantically as one car swerved over an arc of sidewalk to miss another.

The signal changed to green, the cars kept on coming for about thirty seconds and then dwindled to an occasional light-runner. Barlow crossed warily and leaned against a vending machine, blowing big breaths.

Look natural, he told himself. Do something normal. Buy something from the machine.

He fumbled out some change, got a newspaper for a dime, a handkerchief for a quarter and a candy bar for another quarter.

The faint chocolate smell made him ravenous suddenly. He clawed at the glassy wrapper printed “CRIGGLIES” quite futilely for a few seconds, and then it divided neatly by itself. The bar made three good bites, and he bought two more and gobbled them down.

Thirsty, he drew a carbonated orange drink in another one of the glassy wrappers from the machine for another dime. When he fumbled with it, it divided neatly and spilled all over his knees. Barlow decided he had been there long enough and walked on.

The shop windows were—shop windows. People still wore and bought clothes, still smoked and bought tobacco, still ate and bought food. And they still went to the movies, he saw with pleased surprise as he passed and then returned to a glittering place whose sign said it was THE BIJOU.

The place seemed to be showing a quintuple feature, Babies Are Terrible, Don’t Have Children, and The Canali Kid.

It was irresistible; he paid a dol- lar and went in.

He caught the tail-end of The Canali Kid in three-dimensional, full-color, full-scent production. It appeared to be an interplanetary saga winding up with a chase scene and a reconciliation between estranged hero and heroine. Babies Are Terrible and Don’t Have Children were fantastic arguments against parenthood—the grotesquely exaggerated dangers of painfully graphic childbirth, vicious children, old parents beaten and starved by their sadistic offspring. The audience, Barlow astoundedly noted, was placidly champing sweets and showing no particular signs of revulsion.

The Coming Attractions drove him into the lobby. The fanfares were shattering, the blazing colors blinding, and the added scents stomach-heaving.

When his eyes again became accustomed to the moderate lighting of the lobby, he groped his way to a bench and opened the newspaper he had bought. It turned out to be The Racing Sheet, which afflicted him with a crushing sense of loss. The familiar boxed index in the lower left hand corner of the front page showed almost unbearably that Churchill Downs and Empire City were still in business—

Blinking back tears, he turned to -the Past Performances at Churchill. They weren’t using abbreviations any more, and the pages because of that were single-column instead of double. But it was all the same—or was it?

He squinted at the first race, a three-quarter-mile maiden claimer for thirteen hundred dollars. Incredibly, the track record was two minutes, ten and three-fifths seconds. Any beetle in his time could have knocked off the three-quarter in one-fifteen. It was the same for the other distances, much worse for route events.

What the hell had happened to everything?

He studied the form of a five-year-old brown mare in the second and couldn’t make head or tail of it. She’d won and lost and placed and showed and lost and placed without rhyme or reason. She looked like a front-runner for a couple of races and then she looked like a no-good pig and then she looked like a mudder but the next time it rained she wasn’t and then she was a stayer and then she was a pig again. In a good five-thousand-dollar allowances event, too!

Barlow looked at the other entries and it slowly dawned on him that they were all like the five-year-old brown mare. Not a single damned horse running had the slightest trace of class.

Somebody sat down beside him and said, “That’s the story.”

Barlow whirled to his feet and saw it was Tinny-Peete, his driver.

“I was in doubts about telling you,” said the psychist, “but I see you have some growing suspicions of the truth. Please don’t get excited. It’s all right, I tell you.”

“So you’ve got me,” said Barlow.

“Got you?”

“Don’t pretend. I can put two and two together. You’re the secret police. You and the rest of the aristocrats live in luxury on the sweat of these oppressed slaves. You’re afraid of me because you have to keep them ignorant.”

There was a bellow of bright laughter from the psychist that got them blank looks from other patrons of the lobby. The laughter didn’t sound at all sinister.

“Let’s get out of here,” said Tinny-Peete, still chuckling. “You couldn’t possibly have it more wrong.” He engaged Barlow’s arm and led him to the street. “The actual truth is that the millions of workers live in luxury on the sweat of the handful of aristocrats. I shall probably die before my time of overwork unless—” He gave Barlow a speculative look. “You may be able to help us.”

“I know that gag,” sneered Bar- low. “I made money in my time and to make money you have to get people on your side. Go ahead and shoot me if you want, but you’re not going to make a fool out of me.”

“You nasty little ingrate!” snapped the psychist, with a kaleidoscopic change of mood. “This damned mess is all your fault and the fault of people like you! Now come along and no more of your nonsense.”

He yanked Barlow into an office building lobby and an elevator that, disconcertingly, went whoosh loudly as it rose. The real estate man’s knees were wobbly as the psychist pushed him from the elevator, down a corridor and into an office.

A hawk-faced man rose from a plain chair as the door closed behind them. After an angry look at Barlow, he asked the psychist, “Was I called from the Pole to inspect this—this—?’’

“Unget updandered. I’ve dee-probed etfind quasichance exhim Poprobattackline,” said the psychist soothingly.

“Doubt,” grunted the hawk-faced man.

“Try,” suggested Tinny-Peete.

“Very well. Mr. Barlow, I understand you and your lamented had no children.”

“What of it?”

“This of it. You were a blind, selfish stupid ass to tolerate economic and social conditions which penalized child-bearing by the prudent and foresighted. You made us what we are today, and I want you to know that we are far from satisfied. Damn-fool rockets! Damn-fool automobiles! Damn-fool cities with overhead ramps!”

“As far as I can see,” said Barlow, “you’re running down the best features of time. Are you crazy?”

“The rockets aren’t rockets. They’re turbo-jets — good turbo-jets, but the fancy shell around them makes for a bad drag. The automobiles have a top speed of one hundred kilometers per hour—a kilo- meter is, if I recall my paleolinguistics, three-fifths of a mile—and the speedometers are all rigged accordingly so the drivers will think they’re going two hundred and fifty. The cities are ridiculous, expensive, unsanitary, wasteful conglomerations of people who’d be better off and more productive if they were spread over the countryside.

“We need the rockets and trick speedometers and cities because, while you and your kind were being prudent and foresighted and not having children, the migrant workers, slum dwellers and tenant farmers were shiftlessly and short-sightedly having children—breeding, breeding. My God, how they bred!”

“Wait a minute,” objected Barlow. “There were lots of people in our crowd who had two or three children.”

“The attrition of accidents, illness, wars and such took care of that. Your intelligence was bred out. It is gone. Children that should have been born never were. The just-average, they’ll-get-along majority took over the population. The average IQ now is 45.”

“But that’s far in the future—” “So are you,” grunted the hawk-faced man sourly.

“But who are you people?”

“Just people—real people. Some generations ago, the geneticists realized at last that nobody was going to pay any attention to what they said, so they abandoned words for deeds. Specifically, they formed and recruited for a closed corporation intended to maintain and improve the breed. We are their descendants, about three million of us. There are five billion of the others, so we are their slaves.

“During the past couple of years I’ve designed a skyscraper, kept Billings Memorial Hospital here in Chicago running, headed off war with Mexico and directed traffic at LaGuardia Field in New York.”

“I don’t understand! Why don’t you let them go to hell in their own way?”

The man grimaced. “We tried it once for three months. We holed up at the South Pole and waited. They didn’t notice it. Some drafting-room people were missing, some chief nurses didn’t show up, minor government people on the non-policy level couldn’t be located. It didn’t seem to matter.

“In a week there was hunger. In two weeks there were famine and plague, in three weeks war and anarchy. We called off the experiment; it took us most of the next generation to get things squared away again.”

“But why didn’t you let them kill each other off?”

“Five billion corpses mean about five hundred million tons of rotting flesh.”

Barlow had another idea. “Why don’t you sterilize them?”

“Two and one-half billion operations is a lot of operations. Because they breed continuously, the job would never be done.”

“I see. Like the marching Chinese!”

“Who the devil are they?”

“It was a—uh—paradox of my time. Somebody figured out that if all the Chinese in the world were to line up four abreast, I think it was, and start marching past a given point, they’d never stop because of the babies that would be born and grow up before they passed the point.”

“That’s right. Only instead of ‘a given point,’ make it ‘the largest conceivable number of operating rooms that we could build and staff. There could never be enough.”

“Say!” said Barlow. “Those movies about babies—was that your propaganda?”

“It was. It doesn’t seem to mean a thing to them. We have abandoned the idea of attempting propaganda contrary to a biological drive.”

“So if you work with a biological drive—?”

“I know of none which is consistent with inhibition of fertility.”

Barlow’s face went poker-blank, the result of years of careful discipline. “You don’t, huh? You’re the great brains and you can’t think of any?”

“Why, no,” said the psychist innocently. “Can you?”

“That depends. I sold ten thousand acres of Siberian tundra—through a dummy firm, of course—after the partition of Russia. The buyers thought they were getting improved building lots on the outskirts of Kiev. I’d say that was a lot tougher than this job.”

“How so?” asked the hawk- faced man.

“Those were normal, suspicious customers and these are morons, born suckers. You just figure out a con they’ll fall for; they won’t know enough to do any smart checking.”

The psychist and the hawk-faced man had also had training; they kept themselves from looking with sudden hope at each other.

“You seem to have something in mind,” said the psychist.

Barlow’s poker face went blanker still. “Maybe I have. I haven’t heard any offer yet.”

“There’s the satisfaction of knowing that you’ve prevented Earth’s resources from being so plundered,” the hawk-faced man pointed out, “that the race will soon become extinct.”

“I don’t know that,” Barlow said bluntly. “All I have is your word.”

“If you really have a method, I don’t think any price would be too great,” the psychist offered.

“Money,” said Barlow.

“All you want.”

“More than you want,” the hawk-faced man corrected.

“Prestige,” added Barlow. “Plenty of publicity. My picture and my name in the papers and over TV every day, statues to me, parks and cities and streets and other things named after me. A whole chapter in the history books.”

The psychist made a- facial sign to the hawk-faced man that meant, “Oh, brother!”

The hawk-faced man signaled back, “Steady, boy!”

“It’s not too much to ask,” the psychist agreed.

Barlow, sensing a seller’s market, said, “Power!”

“Power?” the hawk-faced man repeated puzzledly. “Your own hydro station or nuclear pile?”

“I mean a world dictatorship with me as dictator!”

“Well, now —” said the psychist, but the hawk-faced man interrupted, “It would take a special emergency act of Congress but the situation warrants it. I think that can be guaranteed.”

“Could you give us some indication of your plan?” the psychist asked.

“Ever hear of lemmings?”

“No.”

“They are—were, I guess, since you haven’t heard of them—little animals in Norway, and every few years they’d swarm to the coast and swim out to sea until they drowned. I figure on putting some lemming urge into the population.”

“How?”

“I’ll save that till I get the right signatures on the deal.”

The hawk-faced man said, “I’d like to work with you on it, Barlow. My name’s Ryan-Ngana.” He put out his hand.

Barlow looked closely at the hand, then at the man’s face. “Ryan what?”

“Ngana.”

“That sounds like an African name.”

“It is. My mother’s father was a Watusi.”

Barlow didn’t take the hand. “I thought you looked pretty dark. I don’t want to hurt your feelings, but I don’t think I’d be at my best working with you. There must be somebody else just as well qualified, I’m sure.”

The psychist made a facial sign to Ryan-Ngana that meant, “Steady yourself, boy!”

“Very well,” Ryan-Ngana told Barlow. “We’ll see what arrangement can be made.”

“It’s not that I’m prejudiced, you understand. Some of my best friends—”

“Mr. Barlow, don’t give it another thought. Anybody who could pick on the lemming analogy is going to be useful to us.”

And so he would, thought Ryan- Ngana, alone in the office after Tinny-Peete had taken Barlow up to the helicopter stage. So he would. Poprob had exhausted every rational attempt and the new Poprobattacklines would have to be irrational or sub-rational. This creature from the past with his lemming legends and his improved building lots would be a fountain of precious vicious self-interest.

Ryan-Ngana sighed and stretched. He had to go and run the San Francisco subway. Summoned early from the Pole to study Barlow, he’d left unfinished a nice little theorem. Between interruptions, he was slowly constructing an n-dimensional geometry whose foundations and superstructure owed no debt whatsoever to intuition.

Upstairs, waiting for a helicopter, Barlow was explaining to Tinny-Peete that he had nothing against Negroes, and Tinny-Peete wished he had some of Ryan-Ngana’s imperturbability and humor for the ordeal.

The helicopter took them to International Airport where, Tinny-Peete explained, Barlow would leave for the Pole.

The man from the past wasn’t sure he’d like a dreary waste of ice and cold.

“It’s all right,” said the psyehist. “A civilized layout. Warm, pleasant. You’ll be able to work more efficiently there. All the facts at your fingertips, a good secretary—”

“I’ll need a pretty big staff,” said Barlow, who had learned from thousands of deals never to take the first offer.

”I meant a private, confidential one,” said Tinny-Peete readily, “but you can have as many as you want. You’ll naturally have top-primary-top priority if you really have a workable plan.”

“Let’s not forget this dictatorship angle,” said Barlow.

He didn’t know that the psychist would just as readily have promised him deification to get him happily on the “rocket” for the Pole. Tinny-Peete had no wish to be torn limb from limb; he knew very well that it would end that way if the population learned from this anachronism that there was a small elite which considered itself head, shoulders, trunk and groin above the rest. The fact that this assumption was perfectly true and the fact that the elite was condemned by its superiority to a life of the most grinding toil would not be considered; the difference would.

The psychist finally put Barlow aboard the “rocket” with some thirty people—real people—headed for the Pole.

Barlow was airsick all the way because of a post-hypnotic suggestion Tinny-Peete had planted in him. One idea was to make him as averse as possible to a return trip, and another idea was to spare the other passengers from his aggressive, talkative company.

Barlow during the first day at the pole was reminded of his first day in the Army. It was the same now-where-the-hell-are-we-going-to-put-you? business until he took a firm line with them. Then instead of acting like supply sergeants they acted like hotel clerks.

It was a wonderful, wonderfully calculated buildup, and one that he failed to suspect. After all, in his time a visitor from the past would have been lionized.

At day’s end he reclined in a snug underground billet with the 60-mile gales roaring yards over-head, and tried to put two and two together.

It was like old times, he thought—like a coup in real estate where you had the competition by the throat, like a 50-per cent rent boost when you knew damned well there was no place for the tenants to move, like smiling when you read over the breakfast orange juice that the city council had decided to build a school on the ground you had acquired by a deal with the city council. And it was simple. He would just sell tundra building lots to eagerly suicidal lemmings, and that was absolutely all there was to solving the Problem that had these double-domes spinning.

They’d have to work out most of the details, naturally, but what the hell, that was what subordinates were for. He’d need specialists in advertising, engineering, communications—did they know anything about hypnotism? That might be helpful. If not, there’d have to be a lot of bribery done, but he’d make sure—damned sure—there were unlimited funds.

Just selling building lots to lemmings…

He wished, as he fell asleep, that poor Verna could have been in on this. It was his biggest, most stupendous deal. Verna—that sharp shyster Sam Immerman must have swindled her…

It began the next day with people coming to visit him. He knew the approach. They merely wanted to be helpful to their illustrious visitor from the past and would he help fill them in about his era, which unfortunately was somewhat obscure historically, and what did he think could be done about the Problem? He told them he was too old to be roped any more, and they wouldn’t get any information out of him until he got a letter of intent from at least the Polar President, and a session of the Polar Congress empowered to make him dictator.

He got the letter and the session. He presented his program, was asked whether his conscience didn’t revolt at its callousness, explained succinctly that a deal was a deal and anybody who wasn’t smart enough to protect himself didn’t deserve protection—”Caveat emp- tor,” he threw in for scholarship, and had to translate it to “Let the buyer beware.’’ He didn’t, he stated, give a damn about either the morons or their intelligent slaves; he’d told them his price and that was all he was interested in.

Would they meet it or wouldn’t they?

The Polar President offered to resign in his favor, with certain temporary emergency powers that the

Polar Congress would vote him if he thought them necessary. Barlow demanded the title of World Dictator, complete control of world finances, salary to be decided by himself, and the publicity campaign and historical writeup to begin at once.

“As for the emergency powers,” he added, “they are neither to be temporary nor limited.”

Somebody wanted the floor to discuss the matter, with the declared hope that perhaps Barlow would modify his demands.

“You’ve got the proposition,” Barlow said. “I’m not knocking off even ten per cent.”

“But what if the Congress refuses, sir?” the President asked.

“Then you can stay up here at the Pole and try to work it out yourselves. I’ll get what I want from the morons. A shrewd operator like me doesn’t have to compromise; I haven’t got a single competitor in this whole cockeyed moronic era.”

Congress waived debate and voted by show of hands. Barlow won unanimously.

“You don’t know how close you came to losing me,” he said in his first official address to the joint Houses. “I’m not the boy to haggle; either I get what I ask or I go elsewhere. The first thing I want is to see designs for a new palace for me—nothing unostentatious, either—and your best painters and sculptors to start working on my portraits and statues. Meanwhile, I’ll get my staff together.”

He dismissed the Polar President and the Polar Congress, telling them that he’d let them know when the next meeting would be.

A week later, the program started with North America the first target.

Mrs. Garvy was resting after dinner before the ordeal of turning on the dishwasher. The TV, of course, was on and it said: “Oooh!”—long, shuddery and ecstatic, the cue for the Parfum Assault Criminale spot commercial. “Girls,” said the announcer hoarsely, “do you want your man? It’s easy to get him—easy as a trip to Venus.”

“Huh?” said Mrs. Garvy.

“Wassamatter?” snorted her husband, starting out of a doze.

“Ja hear that?”

“Wha’?”

“He said ’easy like a trip to Venus.’”

“So?”

“Well, I thought ya couldn’t get to Venus. I thought they just had that one rocket thing that crashed on the Moon.”

“Aah, women don’t keep up with the news,” said Garvy righteously, subsiding again.

“Oh,” said his wife uncertainly.

And the next day, on Henry’s Other Mistress, there was a new character who had just breezed in: Buzz Rentshaw, Master Rocket Pilot of the Venus run. On Henry’s Other Mistress, “the broadcast drama about you and your neighbors, folksy people, ordinary people, real people!”

Mrs. Garvy listened with amazement over a cooling cup of coffee as Buzz made hay of her hazy convictions.

MONA: Darling, it’s so good to see you again!

BUZZ: You don’t know how I’ve missed you on that dreary Venus run.

SOUND: Venetian blind run down, key turned in door lock.

MONA: Was it very dull, dearest?

BUZZ: Let’s not talk about my humdrum job, darling. Let’s talk about us.

SOUND: Creaking bed.

Well, the program was back to normal at last. That evening Mrs. Garvy tried to ask again whether her husband was sure about those rockets, but he was dozing right through Take It and Stick It, so she watched the screen and forgot the puzzle.

She was still rocking with laughter at the gag line, “Would you buy it for a quarter?” when the commercial went on for the detergent powder she always faithfully loaded her dishwasher with on the first of every month.

The announcer displayed mountains of suds from a tiny piece of the stuff and coyly added: “Of course, Cleano don’t lay around for you to pick up like the soap root on Venus, but it’s pretty’ cheap and it’s almost pretty near just as good. So for us plain folks who ain’t lucky enough to live up there on Venus, Cleano is the real cleaning stuff!”

Then the chorus went into their “Cleano-is-the-stuff” jingle, but Mrs. Garvy didn’t hear it. She was a stubborn woman, but it occurred to her that she was very sick indeed. She didn’t want to worry her husband. The next day she quietly made an appointment with her family freud.

In the waiting room she picked up a fresh new copy of Readers Pablum and put it down with a faint palpitation. The lead article, according to the table of contents on the cover, was titled “The Most Memorable Venusian I Ever Met.”

“The freud will see you now,” said the nurse, and Mrs. Garvy tottered into his office.

His traditional glasses and whiskers were reassuring. She choked out the ritual: “Freud, forgive me, for I have neuroses.”

He chanted the antiphonal: “Tut, my dear girl, what seems to be the trouble?”

“I got like a hole in the head,” she quavered. “I seem to forget all kinds of things. Things like everybody seems to know and I don’t.”

“Well, that happens to everybody occasionally, my dear. I suggest a vacation on Venus.”

The freud stared, open-mouthed, at the empty chair. His nurse came in and demanded, “Hey, you see how she scrammed? What was the matter with her?”

He took off his glasses and whiskers meditatively. “You can search me. I told her she should maybe try a vacation on Venus.” A momentary bafflement came into his face and he dug through his desk drawers until he found a copy of the four-color, profusely illustrated journal of his profession. It had come that morning and he had lip-read it, though looking mostly at the pictures. He leafed through to the article Advantages of the Planet Venus in Rest Cures.

“It’s right there,” he said.

The nurse looked. “It sure is,” she agreed. “Why shouldn’t it be?” “The trouble with these here neurotics,” decided ‘the freud, “is that they all the time got to fight reality. Show in the next twitch.”

He put on his glasses and whiskers again and forgot Mrs. Garvy and her strange behavior.

“Freud, forgive me, for I have neuroses.”

“Tut, my dear girl, what seems to be the trouble?”

Like many cures of mental disorders, Mrs. Garvy’s was achieved largely by self-treatment. She disciplined herself sternly out of the crazy notion that there had been only one rocket ship and that one a failure. She could join without wincing, eventually, in any conversation on the desirability of Venus as a place to retire, on its fabulous floral profusion. Finally she went to Venus.

All her friends were trying to book passage with the Evening Star Travel and Real Estate Corporation, but naturally the demand was crushing. She considered herself lucky to get a seat at last for the two-week summer cruise. The space ship took off from a place called Los Alamos, New Mexico. It looked just like all the spaceships on television and in the picture magazines, but was more comfortable than you would expect.

Mrs. Garvy was delighted with the fifty or so fellow-passengers assembled before takeoff. They were from all over the country and she had a distinct impression that they were on the brainy side. The captain, a tall, hawk-faced, impressive fellow named Ryan-Something or other, welcomed them aboard and trusted that their trip would be a memorable one. He regretted that there would be nothing to see because, “due to the meteorite season,” the ports would be dogged down. It was disappointing, yet re- assuring that the line was taking no chances.

There was the expected momentary discomfort at takeoff and then two monotonous days of droning travel through space to be whiled away in the lounge at cards or craps. The landing was a routine bump and the voyagers were Issued tablets to swallow to immunize them against any minor ailments.

When the tablets took effect, the lock was opened and Venus was theirs.

It looked much like a tropical island on Earth, except for a blanket of cloud overhead. But it had a heady, other-worldly quality that was intoxicating and glamorous.

The ten days of the vacation were suffused with a hazy magic. The soap root, as advertised, was free and sudsy. The fruits, mostly tropical varieties transplanted from Earth, were delightful. The simple shelters provided by the travel company were more than adequate for the balmy days and nights.

It was with sincere regret that the voyagers filed again into the ship, and swallowed more tablets doled out to counteract and sterilize any Venus illnesses they might unwittingly communicate to Earth.

Vacationing was one thing. Power politics was another.

At the Pole, a small man was in a soundproof room, his face deathly pale and his body limp in a straight chair.

In the American Senate Chamber, Senator Hull-Mendoza (Synd., N. Cal.) was saying: “Mr. President and gentlemen, I would be remiss in my duty as a legislature if’n I didn’t bring to the attention of the au-gust body I see here a perilous situation which is fraught with peril. As is well known to members of this au-gust body, the perfection of space flight has brought with it a situation I can only describe as fraught with peril. Mr. President and gentlemen, now that swift American rockets now traverse the trackless void of space between this planet and our nearest planetarial neighbor in space—and, gentlemen, I refer to Venus, the star of dawn, the brightest jewel in fair Vulcan’s diadome—now, I say, I want to inquire what steps are being taken to colonize Venus with a vanguard of patriotic citizens like those minutemen of yore.

“Mr. President and gentlemen! There are in this world nations, envious nations—I do not name Mexico—who by fair means or foul may seek to wrest from Columbia’s grasp the torch of freedom of space; nations whose low living standards and innate depravity give them an unfair advantage over the citizens of our fair republic.

“This is my program: I suggest that a city of more than 100,000 population be selected by lot. The citizens of the fortunate city are to be awarded choice lands on Venus free and dear, to have and to hold and convey to their descendants. And the national government shall provide free transportation to Venus for these citizens. And this program shall continue, city by city, until there has been deposited on Venus a sufficient vanguard of citizens to protect our manifest rights in that planet.

“Objections will be raised, for carping critics we have always with us. They will say there isn’t enough steel. They will call it a cheap give-away. I say there is enough steel for one city’s population to be transferred to Venus, and that is all that is needed. For when the time comes for the second city to be transferred, the first, emptied city can be wrecked for the needed steel! And is it a giveaway? Yes! It is the most glorious giveaway in the history of mankind! Mr. President and gentlemen, there is no time to waste—Venus must be American!”

Black-Kupperman, at the Pole, opened his eyes and said feebly, “The style was a little uneven. Do you think anybody’ll notice?’’

“You did fine, boy; just fine,” Barlow reassured him.

Hull-Mendoza’s bill became law. Drafting machines at the South Pole were busy around the clock and the Pittsburgh steel mills spewed millions of plates into the Los Alamos spaceport of the Evening Star Travel and Real Estate Corporation. It was going to be Los Angeles, for logistic reasons, and the three most accomplished psycho-kineticists went to Washington and mingled in the crowd at the drawing to make certain that the Los Angeles capsule slithered into the fingers of the blind-folded Senator.

Los Angeles loved the idea and a forest of spaceships began to blossom in the desert. They weren’t very good space ships, but they didn’t have to be.

A team at the Pole worked at Barlow’s direction on a mail setup. There would have to be letters to and from Venus to keep the slightest taint of suspicion from arising. Luckily Barlow remembered that the problem had been solved once before—by Hitler. Relatives of persons incinerated in the furnaces of Lublin or Majdanek continued to get cheery postal cards.

The Los Angeles flight went off on schedule, under tremendous press, newsreel and television coverage. The world cheered the gallant Angelenos who were setting off on their patriotic voyage to the land of milk and honey. The forest of spaceships thundered up, and up, and out of sight without untoward incident. Billions envied the Angelenos, cramped and on short rations though they were.

Wreckers from San Francisco, whose capsule came up second, moved immediately into the city of the angels for the scrap steel their own flight would require. Senator Hull-Mendoza’s constituents could do no less.

The president of Mexico, hypnotically alarmed at this extension of yanqui imperialismo beyond the stratosphere, launched his own Venus-colony program.

Across the water it was England versus Ireland, France versus Germany, China versus Russia, India versus Indonesia. Ancient hatreds grew into the flames that were rocket ships assailing the air by hundreds daily.

Dear Ed, how are you? Sam and I are fine and hope you are fine. Is it nice up there like they say with food and close grone on trees? I drove by Springfield yesterday and it sure looked funny all the buildings down but of coarse it is worth it we have to keep the greasers in their place. Do you have any truble with them on Venus? Drop me a line some time. Your loving sister, Alma.

Dear Alma, I am fine and hope you are fine. It is a fine place here fine climate and easy living. The doctor told me today that I seem to be ten years younger. He thinks there is something in the air here keeps people young. We do not have much trouble with the greasers here they keep to theirselves it is just a question of us outnumbering them and staking out the best places for the Americans. In South Bay I know a nice little island that I have been saving for you and Sam with lots of blanket trees and ham bushes. Hoping to see you and Sam soon, your loving brother, Ed.

Sam and Alma were on their way shortly.

Poprob got a dividend in every nation after the emigration had passed the halfway mark. The lonesome stay-at-homes were unable to bear the melancholy of a low population density; their conditioning had been to swarms of their kin. After that point it was possible to foist off the crudest stripped-down accommodations on would-be emigrants; they didn’t care.

Black-Kupperman did a final job on President Hull-Mendoza, the last job that genius of hypnotics would ever do on any moron, important or otherwise.

Hull-Mendoza, panic-stricken by his presidency over an emptying nation, joined his constituents. The Independence, aboard which traveled the national government of America, was the most elaborate of all the spaceships—bigger, more comfortable, with a lounge that was handsome, though cramped, and cloakrooms for Senators and Representatives. It went, however, to the same place as the others and Black-Kupperman killed himself, leaving a note that stated he “couldn’t live with my conscience.”

The day after the American President departed, Barlow flew into a rage. Across his specially built desk were supposed to flow all Poprob high-level documents and this thing—this outrageous thing—called Poprobterm apparently had got into the executive stage before he had even had a glimpse of it!

He buzzed for Rogge-Smith, his statistician. Rogge-Smith seemed to be at the bottom of it. Poprobterm seemed to be about first and second and third derivatives, whatever they were. Barlow had a deep distrust of anything more complex than what he called an “average.”

While Rogge-Smith was still at the door, Barlow snapped, “What’s the meaning of this? Why haven’t I been consulted? How far have you people got and why have you been working on something I haven’t authorized?”

“Didn’t want to bother you, Chief,” said Rogge-Smith. “It was really a technical matter, kind of a final cleanup. Want to come and see the work?”

Mollified, Barlow followed his statistician down the corridor.

“You still shouldn’t have gone ahead without my okay,” he grumbled. “Where the hell would you people have been without me?”

“That’s right, Chief. We couldn’t have swung it ourselves; our minds just don’t work that way. And all that stuff you knew from Hitler—it wouldn’t have occurred to us. Like poor Black-Kupperman.”

They were in a fair-sized machine shop at the end of a slight upward incline. It was cold. Rogge-Smith pushed a button that started a motor, and a flood of arctic light poured in as the roof parted slowly. It showed a small spaceship with the door open.

Barlow gaped as Rogge-Smith took him by the elbow and his other boys appeared: Swenson-Swenson, the engineer; Tsutsugimushi-Duncan, his propellants man; Kalb-French, advertising.

“In you go, Chief,” said Tsutsugimushi-Duncan. “This is Poprobterm.”

“But I’m the world Dictator!”

“You bet, Chief. You’ll be in history, all right—but this is necessary, I’m afraid.”

The door was closed. Acceleration slammed Barlow cruelly to the metal floor. Something broke and warm, wet stuff, salty-tasting, ran from his mouth to his chin. Arctic sunlight through a port suddenly became a fierce lancet stabbing at his eyes; he was out of the atmosphere.

Lying twisted and broken under the acceleration, Barlow realized that some things had not changed, that Jack Ketch was never asked to dinner however many shillings you paid him to do your dirty work, that murder will out, that crime pays only temporarily.

The last thing he learned was that death is the end of pain.

Cyril M. Kornbluth (1923-1958) was an American writer who shot to fame by publishing his stories in various science fiction magazines. He was associated with the Futurians. His stories are often dystopic warnings of what is to come in the future.