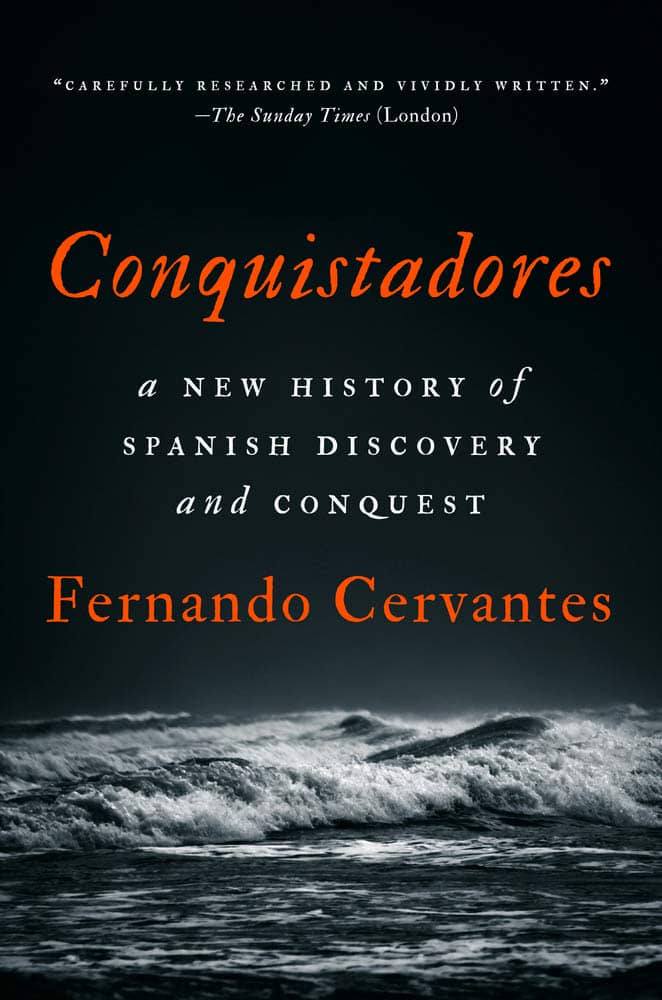

In his well-written, and impressively documented book, Conquistadores: A New History of Spanish Discovery and Conquest, Mexican historian Fernando Cervantes (University of Bristol) tells us who these men were that beat the best warriors among the Indigenous People of the New World at their own war-making and conquering game—and how they did it. They certainly had diversity and inclusiveness. Christopher Columbus’ father was a Genoese wool-worker. Hernán Cortés came from a family of ancient lineage, though not wealthy. Most were of modest means. Cervantes does not mention that Francisco Pizarro is said to have been a swineherd as a boy.

The early chapters examine Columbus’ personality, his remarkable voyage, and the conquistadores’ Caribbean settlements. The later chapters focus on the conquests of Mesoamerica, the Inca Empire and adjacent lands, and the conquest of Florida. The final pages offer a thoughtful examination of the fate of the conquistadores’ descendants in the Americas, who were replaced in power and status by rulers and bureaucrats, sent from Spain by the Spanish Crown.

Cervantes minces no words describing the Spaniards’ exploitation of the Tainos with the system of encomiendas, which was designed to end slavery and facilitate evangelization, but turned into another form of slavery. Cervantes displays a deep knowledge of the religious context when telling us how Dominican priests in the Caribbean, inspired by the writings and life of Dominican lay sister, Saint Catherine of Siena, excoriated the conquistadores for their mistreatment of the Tainos.

The Tainos had been long preyed upon by their fellow Indigenous People, the Carib. The Encyclopaedia Britannica Online (as of October 23 2021) cautiously describes some of the Carib’s cultural practices:

“The Island Carib, who were warlike (and allegedly cannibalistic) were immigrants from the mainland who, after driving the Arawak from the Lesser Antilles, were expanding when the Spanish arrived. Peculiarly, the Carib language was spoken only by the men; women spoke Arawak. Raids upon other peoples provided women who were kept as slave-wives; the male captives were tortured and killed. The [Carib] men were individualistic warriors and boasted of their heroic exploits.”

Columbus ended the Carib’s terrorizing, enslaving, and (“allegedly”) eating of Indigenous People. Cervantes informs us that, when Columbus sent two Carib prisoners to the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella ordered them freed because they were now her subjects and should not be mistreated.

Knowledge of the Spanish system of encomiendas and of their eventual abolition (new encomiendas were prohibited in 1721 but not abolished until the end of the eighteenth century), as well as knowledge of the conquistadores’ ruthlessness, should be placed in the historical context of the cultural practices of Indigenous People prior to the Europeans’ arrival. Cervantes’ book gives us this context.

The Indigenous People’s Cultural Practices

Cervantes’ book shows that Indigenous People in Mesoamerica and South America practiced slavery and were ruthless in their treatment of other Indigenous People. But also throughout North America Indigenous People practiced slavery of one kind or another, and were ruthless against other Indigenous People. As historian Francis Parkman observed in The Oregon Trail and The Conspiracy of Pontiac,captured enemy warriors in North America were sometimes tortured and mutilated: one of their feet might be cut to prevent escape.

A more recent book, edited by Richard Chacón and Rubén Mendoza, North American Indigenous Warfare and Ritual Violence, presents further evidence. In its press release, the University of Arizona Press laments the all-too-familiar academic opposition to ideologically inconvenient facts:

“Despite evidence of warfare and violent conflict in pre-Columbian North America, scholars argue that the scale and scope of Native American violence is exaggerated. They contend that scholarly misrepresentation has denigrated indigenous peoples when in fact they lived together in peace and harmony. In rebutting that contention, this groundbreaking book presents clear evidence—from multiple academic disciplines—that indigenous populations engaged in warfare and ritual violence long before European contact.”

For a succinct popular account of violence among North American Indigenous People, see Bill Donohue, “The Dark Side of Indigenous People.”

In Mesoamerica, among the Mexica (“the Aztecs”) and other Indigenous People, war captives were sacrificed to the gods and/or eaten.

We learn in Cervantes’s book that Cortés admonished the cacique of Zautla, a town loyal to the Mexica ruler, Moctezuma, to desist from their practice of sacrificing humans and eating them. But the cacique, “who had no qualms about sacrificing fifty men at a festival,” responded that he would not do anything without Moctezuma’s consent and that Moctezuma had 100,000 warriors and sacrificed 20,000 men every year.”

The Mexica use of atrocities and terror as tools of war and politics, and not just as “religious practices,” as they are usually explained by academics, is exemplified by the Mexica ruler Cuauhtemoc’s treatment of his Spanish prisoners: Cervantes tells us that, after Cuauhtemoc had them sacrificed, he “sent their limbs “to be distributed to the nearby towns as a portent of Mexica supremacy.” What the nearby towns did with those limbs is left to the reader’s imagination.

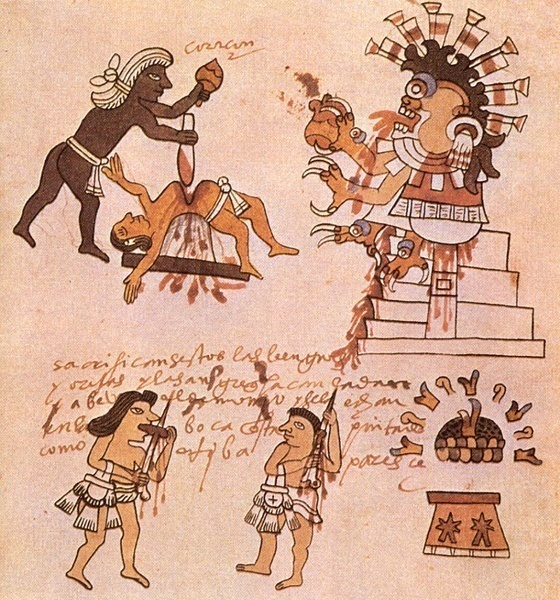

The Mexica made a yearly war, poetically called “war of the flowers,” upon other Indigenous People, to capture them alive and sacrifice thousands of them to the god Huitzilopotchli on top of their impressive pyramid-temples, where a priest ripped out the palpitating heart and kicked the body down the pyramid.

As anthropologist Michael Harner explains, the body was then “carried off to be butchered.” Harner complained that

“These enormous numbers [of killed humans] call for consideration of what the Aztecs did with the bodies after the sacrifices. Evidence of Aztec cannibalism has been largely ignored or consciously or unconsciously covered up…. The major twentieth-century books on the Aztecs barely mention it; others bypass the subject completely. Probably some modern Mexicans and anthropologists have been embarrassed by the topic: the former partly for nationalistic reasons; the latter partly out of a desire to portray native peoples in the best possible light. Ironically, both these attitudes may represent European ethnocentrism regarding cannibalism.… A search of the sixteenth-century literature, however, leaves no doubt as to the prevalence of cannibalism among the central Mexicans. The Spanish conquistadores wrote amply about it, as did several Spanish priests who engaged in ethnological research on Aztec culture shortly after the conquest. Among the latter, [Franciscan priest] Bernardino de Sahagún is of particular interest because his informants were former Aztec nobles, who supplied dictated or written information in the Aztec language, Nahuatl” (“The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice,” Natural History, April 1977).

During his examination of the evidence of cannibalism in the remains of Indigenous People in the American Southwest, anthropologist Christy G. Turner concluded (Man Corn: Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric American Southwest) that cannibalism was introduced among the Anasazi by Mexica immigrants, and he complained that research on cannibalism has been censored and demonized. An analogous complaint is eloquently articulated by Nirmal Dass (“Cannibalism And Child Sacrifice Are Obvious Evils. Why Can’t Cultural Relativists Admit That?”).

Slaves were also given as presents. Sexual slavery was part of the culture. Doña Marina, Cortés’ interpreter and mistress, was sold as a girl by her Mexica family to Maya slave traders. She was later given as a present to Cortés. Today she is widely regarded as a “traitor” to her Indigenous People. But what kind of allegiance should Marina have felt towards the Mexica, who sold her to the Maya? With Cortés, Marina attained a position she never had, and was unlikely to have, among the Indigenous People. She was admired by the Spaniards for her intelligence and knowledge of the land, its people, and Maya, Nahuatl, and Spanish languages. Perhaps Marina should be praised as a remarkable woman who paid back with interest the Indigenous People who mistreated her.

Cervantes explains that the Totonacs, a nation subjugated by the Mexica, sent envoys to Cortés to tell him that the Mexica were intolerable tyrants who oppressed them. This was one of the first indications Cortés had of the alliances he could establish with Indigenous People oppressed by the Mexica, which would help him conquer their empire with a few hundred Spaniards.

Smallpox, Cervantes writes, was “inadvertently introduced by Spanish explorers.” The narrative stating that the disease so decimated the Mexica that it made their conquest by Cortés possible was debunked (though to no avail because this debunking, as usual, has been largely ignored by academics) – by historian Francis J. Brooks. He concluded that “In the West Indies and Mexico, where smallpox was first carried from Euro-Asia-Africa to the rest of the world, a detailed examination of the historical sources calls into question the melodramatic stories of prairie-fire epidemics killing off the majority of the population in no more than a few years” (“Revising the Conquest of Mexico: Smallpox, Sources, and Populations,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Summer 1993).

Moreover, Cervantes reminds us that the conquistadores themselves got sick and died, unaccustomed as they were to their new environment. The hot and humid climate, the insalubrious air, the dysentery, the fatigue, and even hunger played havoc among the Spaniards. Barely eight months after the conquistador Ovando arrived in the New World, 1000 of his men had already died and 500 were sick. Hernando de Soto got ill and died in Florida at the age of 41. Pizarro’s men got sick with a strange disease that began with pain in the muscles and culminated with “large, disfiguring boils.” Several of his men died of this mysterious disease. But they soldiered on. The resilience of these tough Spaniards in the face of such physical adversity is remarkable.

Cervantes does not mention that the hot and humid climate also rendered their limited number of matchlock and powder arquebuses unreliable and their steel armor unwearable, so much so that, as conquistador Bernal Díaz tells us in his Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España,they had to adopt the Indigenous People’s cotton armor.

In North America, the Mayflower Pilgrims, too, got sick and died from illnesses and malnutrition. Many of those who came in the Mayflower grew ill and died.

Cervantes gives numerous examples of the Mexica’s ruthlessness towards other Indigenous People and the conquistadores. But he also tells us that they were ruthless in the training of their own people, which made them the best fighters among the Indigenous People of Mesoamerica—no small feat since Indigenous People in Mesoamerica were warrior-nations.

For the Mexica, as for most Indigenous People, cowardice was the worst possible feature of a man’s character. Women did not enter into such considerations of character because they were not part of the warrior contingents. They engaged in domestic, agricultural and low-level commercial activities.

Cervantes explains this Mexica military superiority over other Indigenous People by calling attention to their formidable training of men as warriors from childhood: “Their toughness and discipline had been imposed from an early age through the education system of the calmecac (‘the house of lineage’), which put the sons of the nobility through a rigorously disciplined religious and military training and the telpochcalli (‘the house of youth”), in which the commoners and the younger or illegitimate sons of the nobility received theirs. A generation after the conquest, native nobles could still recall the stern words of their parents the day they were packed off to school at an early age, warning them that they would not be honored or esteemed, but ‘looked down upon, humiliated, and despised.’ This was a system designed ‘to harden your body, and, as parents warned their children, ‘you will cut agave thorns for penance, and you will draw blood with those spines.’” The Spartan mothers could not have been tougher when they would tell their sons to come back from battle with their shield or on top of their shield, but never without their shield.

Cervantes does not mention other punishments meted out to discipline Mexica children. A child who lied would have his tongue pricked with a maguey spine. If a child stole, his body was pierced with maguey spines. Spanking was done with nettle branches. Crying kids would have their mouths stuffed with bitter herbs. Misbehaving children could be tied up and left outside overnight lying on wet ground. Problematic children were held up over a fire where they would breathe the smoke of burning chili, which would also penetrate through their eyes and mouth. When nothing else worked, desperate parents would sell the child as a slave or give the child to the priests to be sacrificed. See the Codex Mendoza for the depictions of these usually glossed over Mexica cultural practices.

Children, usually taken from Indigenous People oppressed by the Mexica, were sacrificed to the god of rain, Tlaloc (also worshipped and sacrificed to by the Maya). Hundreds of skulls of men, women and children have been found in racks of skulls used by the Mexica for public display (tzompantli) in the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan. Many more are expected to be found as the excavations make progress. This finding confirms the truth of the conquistadores’ reports, long dismissed by academics as anti-native propaganda, of entire walls and towers made of human skulls in the big Mexica capital (“Tower of human skulls in Mexico casts new light on Aztecs”).

Cervantes reveals another reason for the Mexica toughness and ferocity as warriors: drugs. “As some Mexica noblemen recalled, those who ingested peyote, the hallucinogenic cactus, or sacred mushrooms, were filled with a drunkenness that lasted two or three days and which gave them courage for battle, destroyed fear, and kept them from thirst and hunger.” This the Spartans did not do.

The Maya And The Inca

The Maya are often referred to, accurately, as the most advanced pre-Columbian civilization. Yet their way of life featured such cultural practices as slavery, the subjugation of women, human sacrifice, and endemic wars among the various Maya nations—wars that even led to the sacrificial “killing of the nations,” told in the sacred book of the Quiché Maya, the Popol Vuh. In fact, one or more of these cultural features were normal in the way of life of the Indigenous People in the New World.

The conquistadores experienced several of these cultural practices. Cervantes explains that, before the conquest of Mexico, Gerónimo de Aguilar’s ship struck shoals and sank; the few survivors reached the Yucatan Maya coast. There, they were captured by one Maya nation. Five of the Spaniards “were sacrificed and eaten.” Aguilar and others were “put in cages to be fattened.” They managed to escape and were received“by a rival cacique…who enslaved them.” Eventually they joined the Maya. Aguilar’s friend had his face and hands tattooed, his ears and nose pierced, and he took a Maya wife. Aguilar claimed he had kept his chastity (he had taken minor orders in Spain), refusing the many women offered to him by his now fellow Indigenous People.

Academics who routinely write about the atrocities of evil white Europeans, who destroyed wonderful civilizations in the New World, and about the Indigenous People’s resistance, often avoid these central features of the Indigenous way of life–features which for us today are rather undesirable, and therefore glossed over or even denied in polite conversation, as well as in teaching and publishing, to avoid any accusation of “racism” (or, more recently, of “white supremacy”). But this avoidance and even opposition, to echo anthropologist Harner, may be yet another form of “European Ethnocentrism,” if not “paternalism,” because such rather unpleasant practices were perfectly normal in the Indigenous culture of the New World. And the inconvenient fact is that these rather unpleasant practices were only ended by the conquistadores.

Though not mentioned by Cervantes, in their vast empire, conquered through their superior capacity for organization, war making, and terrorizing, the Inca perfected the ethnic cleansing of rebellious Indigenous People. And they also practiced human sacrifice: archeologists have found the remains of young girls sacrificed on top of the Andes. The Inca rulers practiced sexual slavery methodically: they had the villages of their empire scoured for the best-looking girls to add to their harems. For all this, see Fernández-Morera, “Inca Garcilaso’s Comentarios Reales, Or Who Tells the Story of a Conquered Civilization?”

For an excellent examination of Inca culture from the debunking point of view of a great archeologist, see Albert Meyers, “Occidentalismo académico, lapsus americanus, y los Incas arqueológicos,” (Revista de Arqueologia Americana, 2017).

As Cervantes puts it, the Inca “concentrated power and wealth in the hands of an endogamous and exclusionary ruling oligarchy.”

The Inca’s terroristic approach to conquest is illustrated by their atrocious way of celebrating victories: Cervantes tells us that “they marked the occasion in a most dramatic manner, by flaying the defeated lords of the Altiplano and, after impaling their heads on poles, fashioning their skins into drums.”

Pizarro’s Conquest Of The Inca Empire

The war between two half-brothers, Inca rulers Atawallpa and Waskhar, was horrific. Cervantes illustrates the use of atrocities and other terror tactics as tools of politics and war among the Inca, with Atawallpa ordering “a sadistic spectacle of the slow torture and painful slaughter of… Waskhar’s wives and children, making sure that the defeated leader was forced to watch.” We learn that Pizarro later adopted some of these methods to punish Manco Capac’s Inca rebellion.

Atawallpa also had an entire squadron of his warriors executed because they flinched before the Spanish horses during Pizarro’s embassy’s visit. Atawallpa then also ordered the officers, their wives and children killed so that no one would dare run away when confronted by the strangers. When Atawallpa learned that Waskhar was coming to Cajamarca, “rather than agreeing with Pizarro that Waskhar should be allowed to arrive in safety, Atawallpa ordered his execution.”

Taking advantage of the scars of this war, and the resentment of Indigenous People oppressed by the Inca, Pizarro, like Cortés, established alliances with them. These alliances helped Pizarro, with a few hundred Spaniards, overcome the Inca. Pizarro also shrewdly handled a spy sent by Atawallpa, so that the spy told Atawallpa that the Spaniards were merely “bearded robbers who could be easily enslaved.”

Cervantes narrates vividly Pizarro’s difficult march towards Cajamarca, during which he fended off ambushes from some local chieftains who feigned friendship and then attacked. In Cajamarca, Pizarro succeeded in his own risky ambush of Atawallpa. Although Atawallpa’s warriors “outnumbered the Spaniards at least ten to one, they soon broke ranks and fled, pursued and cut down by the horsemen… In another echo of Cortes’s capture of Moctezuma, Pizarro seized Atawallpa…”

Repeatedly, Pizarro’s conquistadores’ lightning strikes of expert swordsmanship, on foot and on horse, cut to pieces and scattered the Indigenous battle formations, which always vastly outnumbered them. The Inca warriors’ pre-battle theater of threats against enemies, “which included looking forward with keen anticipation to drinking out of their skulls, adorning themselves ritually with necklaces made from their teeth, playing music with flutes constructed from their bones, and beating drums created from their flayed skins…was magnificent theater but totally ineffective against brutally pragmatic enemies.”

Though a captive, Atawallpa was treated with respect and allowed to meet with his subordinates and continued to give orders and rule his empire. But Pizarro’s plan was to go on to Cusco, where most of the Inca gold supposedly was, and he feared that carrying Atawallpa along would invite attacks to try to free the ruler. Eventually, he agreed with other conquistadores that it was best to kill Atawallpa. A court was set up and Atawallpa was found guilty of “fratricide, polygamy,” cruelty towards his people, and other charges taken from European law that made no sense within the context of Indigenous culture. He was garroted.

Pizarro then quickly installed as new ruler a surviving son of Waskhar, Thupa Wallpa, and convinced the Inca nobility, as well as Tupa Wallpa, to become vassals of Charles V, abandon their gods, and accept Christianity as the way to eternal life after death.

As Cervantes observes, this acquiescence was similar to the eventual acceptance by the Mexica and Maya nobility of vassalage and Christianity, and “Cortes’s admonitions about idolatry, human sacrifice and anthropophagy, and with the consequent need for them to abandon their idols and begin to venerate Christian images.” Put otherwise: in both cases, these great warriors reasoned that their gods obviously were inferior, since these bearded strangers, with their own God, had destroyed with impunity the statues of the gods and defeated the Indigenous People. From these warriors’ cultural point of view, might made right.

Moreover, as Cervantes points out, many Indigenous People, former followers of Waskhar or not, were relieved that Atawallpa was gone; and it was those bearded strangers who finished him off. We learn that, at Jauja, the Wanka received the conquistadores as liberators. Again, we have here echoes of the Indigenous People of Mesoamerica’s glad alliance with Cortés to end the rule of their oppressors, the Mexica. In the later defense of Jauja, in 1534, against a large Inca force, the Wanka were happy to fight alongside the conquistadores and were decisive in their victory. In the North, the Cañari also supported the Spaniards because “they had fresh and bitter memories of the violence with which the Inca had established themselves in the region.”

These alliances of Indigenous People with the conquistadores against other stronger Indigenous People anticipated analogous alliances in North America. Thus in the early 1600s the Algonquin nations (one of which was the Wampanoag, who signed a treaty with the Mayflower Pilgrims, remembered in the American holiday of Thanksgiving) allied themselves with European settlers as a counter to the ferocious Iroquois nations, with whom they had been at war for many years. Later, some North American Indian nations allied themselves with American settlers and with the British or the French in several wars. Some North American Indigenous People also owned and sold black slaves.

The Abolition Of Slavery

Cervantes explains that Pizarro’s execution of Atawallpa was not well received by Charles V and others around him. Cervantes cites the founder of International Law, the Dominican priest Francisco de Vitoria (University of Salamanca): “After a lifetime of studies and experience, no business shocks me more than the corrupt profits and affairs of the Indies. Their very mention freezes the blood in my veins… Neither Atawallpa nor any of his people had ever done the slightest injury to the Christians. Nor given them the slightest ground for making war on them.”

Cervantes points out that Vitoria’s arguments on law, politics, and economics found disciples in brilliant men such as “the Dominicans Domingo de Soto and Melchor Cano and the Jesuits Luis de Molina and Francisco Suárez.”

As Cervantes reminds us, Vitoria’s arguments against the conquistadores used ideas from a long Western tradition on the term “right” (ius in Latin, hence the term iustitia, justice)—from Socrates to Plato, to Aristotle to Roman Law, to Saint Thomas Aquinas.

Vitoria’s arguments on the concept of right addressed slavery, which Cervantes shows was practiced in one form or another by both Indigenous People and the European conquistadores. In his book Esclavage, l’histoire à l’endroit (2020), Africanist Professor Bernard Lugan (University of Lyons) has observed that although all peoples have practiced slavery, it was the white Europeans who abolished slavery first. His observation has been echoed by African intellectuals like Ernst Tigori (R. Ibrahim, “’I ‘m Saddened by the White Man’s Emasculation’: An African Sets the Record Straight”).

Benin Professor Abiola Felix Iroko also has exposed the practice of slavery among black Africans long before the Transatlantic Slave Trade (“Historian: ‘Africans must be condemned for the slave trade’”). Ghana professor John Allenbillah Azumah’s book, The Legacy of Arab Islam in Africa, documents the slave trade of African Blacks by Muslim Arabs long before the Europeans’ arrival.

Some European countries even enforced abolition beyond their frontiers. Between 1807 and 1856, the British Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron, at the cost of the lives of British sailors, attacked the slave traders and liberated over a hundred thousand black Africans. For a succinct popular account of the practice of slavery by Black Africans in West Africa see, “A Brief History of West African Slavery for the Woke.” France abolished slavery in the late eighteenth century and later enforced abolition on its African colonies.

Nevertheless, perhaps the fundamental difference is that the Europeans based their pioneering abolition of slavery not on the decision of a particular “enlightened” ruler, but on religious and philosophical arguments on right and liberty that gradually spread among the culture of their people, eventually gathering enough strength to bring about political decisions; and that these religious and philosophical arguments were not part of the culture of the Indigenous People—or, for that matter, of the culture of other peoples in Africa and Asia. (Cf. Fernández Morera, “Christian Slavery under Islam”).

Today, when politicians, professors, and mobs decry, remove, cover, or destroy the statues of Columbus, Franciscan priest Junípero Serra, and even Thomas Jefferson, and adopt a new version of Rousseau’s “Noble Savage” (replacing it with the Noble Indigenous People), Cervantes’ revealing and contextualizing account of the cultural practices of both Indigenous People and European conquistadores should contribute to a correction of the prevailing narrative—though this is unlikely because too many intereses creados, stake holder interests, now depend on that narrative. For a direct correction, see the open letters by Argentine political scientist and historian Marcelo Gullo Omodeo, and Spanish Arabist and historian Serafín Fanjul, in answer to the Mexican President’s demand for apologies from Spain for the conquest.

Darío Fernández-Morera is Associate Professor Emeritus of Spanish and Portuguese at Northwestern University. He has published several books, and his more recent one, The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise: Muslims, Christians and Jews under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain, has also been translated into French (with a Prologue by philosopher, Arabist, Hebraist and Hellenist Rémi Brague) and into Spanish. He has served in the United States National Council on the Humanities. For more about him, visit his pages here and here.

The featured image shows a Mexica child being punished for stealing or raising his voice against his parents by having his body pierced with maguey spines. Codex Mendoza, ca. 1541-1542.