1.

There are at least two definitions for barbarism, neither sympathetic to the innate dignity of the human person. Barbarism is extreme cruelty or brutality, evoking mindless savagery, callous disregard for life, and a cold-blooded viciousness that brooks no mercy; where barbarism rules, culture and civilization will inevitably be corrupted and crushed. History is witness to this; barbarism has existed since God first created man. Whether it has been brother against brother, tribe against tribe, nation against nation, ruler against subjects, it is only the scale that differs, the results are always the same: civility and culture are early victims of decay, oppression, persecution, and inevitably, proscription.

Barbarism is the antithesis of civilization and the destroyer of culture, though contrary to what one might assume, while lacking in objective principles, it adopts pseudo-principles expressed as saccharine euphemisms to justify its brutal disregard. The most barbaric acts of oppression have always been justified through abstractions—utopian phantasms achievable only through the coarsest application of totalitarian diktat and force. In the post-modern world few are wont to believe there are barbarians and barbarism, except perhaps in the movies; but, to use the words of Thomas Sowell, “The barbarians are not at the gates. They are inside the gates—and have academic tenure, judicial appointments, government grants, and control of the movies, television, and other media.”

The twenty-year war, disastrously lost, in Afghanistan exemplifies what Eighteenth century Scottish philosopher David Hume claimed in A Treatise of Human Nature:

“When our own nation is at war with any other, we detest them under the character of cruel, perfidious, unjust and violent: but always esteem ourselves and allies equitable, moderate and merciful. If the general of our enemies be successful, ‘tis with difficulty we allow him the figure and character of a man. He is a sorcerer: he has a communication with daemons … he is bloody-minded and takes a pleasure in death and destruction. But if the success be on our side, our commander has all the opposite good qualities, and is a pattern of virtue, as well as of courage and conduct. His treachery we call policy: His cruelty is an evil inseparable from war. In short, every one of his faults we either endeavor to extenuate, or dignify it with the name of that virtue, which approaches it. ‘Tis evident that the same method of thinking runs thro’ common life.”

According to David Livingstone Smith, Less Than Human, Hume quite elegantly described what “present-day social psychologists call outgroup bias—the tendency to favor members of one’s own community and discriminate against outsiders (otherwise known as the ‘us and them’ mentality).” When things go badly for our group, tribe, etc., it is due to some perceived injustice—racism the current cri de coeur—but when the shoe is on the other foot, it is because the other brought it upon themselves, they deserved what they got.

“Hume takes the idea of outgroup bias even further by arguing that sometimes we are so strongly biased against others that we stop seeing them as human beings.” He described “three powerful sources of bias, arguing that we naturally favor people who resemble us, who are related to us, or who are nearby. The people who are ‘different’—who are another color, or who speak a different language, or who practice a different religion—people who are not our blood relations or who live far away, are unlikely to spontaneously arouse the same degree of concern in you as members of your family or immediate community.”

Or, one could add, those who differ ideologically, politically, religiously, or any of a myriad of social and cultural diversions.

Immanuel Kant, a German academic, saw things differently. He recognized the human tendency to regard people as means to an end, thus (though he never used the term) dehumanizing others, effectively categorizing them as subhuman creatures. He wrote, “man should not address other human beings in the same way as animals but should regard them as having an equal share in the gifts of nature.” “Equal share” sounds far too much like equity which proves no small comfort. When we regard people as a means, we suspend the moral obligation to treat them as fully human. This then grants free conscience to cancel, ostracize, or exterminate such subhuman creatures as we please.

What is it within the human psyche that permits such dehumanization? How can we objectively know that all people, no matter their superficial distinctiveness, are full members of homo sapiens? Smith writes, “Although we now know that all people are members of the same species, this awareness doesn’t run very deep, and we have a strong unconscious (‘automatic’) tendency to think of foreigners as subhuman creatures. This gut-level assessment often calls the shots for our feelings and behavior. We can bring ourselves to kill foreigners because, deep down, we don’t believe that they are human.”

Closer to home, dehumanization is starkly presented through distraction by abstraction: it is no longer your neighbor, it is not your friend, nor your brother or sister, son or daughter. No, it is the unvaccinated (show me your papers,) the undocumented (no papers required,) the insurrectionists, white supremacists, and domestic terrorists (who they might be is undocumented) that have become the focus, the individual is insignificant, it is the group, the tribe, the cult, the mob that must garner our undivided attention as the greatest existential threat to democracy or its victim.

Smith cites John T. MacCurdy, The Psychology of War (1918), who noted when tensions are high, “[t]he unconscious idea that the foreigner belongs to a rival species becomes a conscious belief that he is a pestiferous type of animal.” There are more than enough examples to prove MacCurdy’s point. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, for whom he dedicated it “to all those who did not live to tell it.” Mao Zedong’s cannibalistic “Cultural Revolution,“ resulting in 60-70 million deaths. The ongoing Islamic jihad against the infidel: “Surely the vilest of animals in Allah’s sight are those who disbelieve” (Koran 8:55).

Victor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, offers a deeply grim portrayal of dehumanization from his experiences in four concentration camps, including Auschwitz near Oświęcim, Poland. It is said that there were days in summer when it snowed in Oświęcim, so heavy were the ashes emitting from the furnaces cremating the dead.

And yet, Frankl survived and wrote what Harold S. Kushner described as one of the most religious sentences written in the twentieth century:

“We have come to know Man as he really is. After all, man is that being who invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord’s Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips.”

Tragically, history is replete with similar dehumanizing pathologies; nothing has changed, man’s barbaric nature continues, hellbent on destroying himself.

2.

According to Richard John Neuhaus, “Culture is the root of politics, and religion is the root of culture.” This proverb commands a hierarchy whose order of importance is much more than illusory. Politics is not the root of the cultural tree but its fruit, culture is not the root of religion but the moral product of reason and objective truth.

Thus, politics to be good and just must be rooted in a culture grounded in natural law and moral and ethical tradition. For the West, for more than a millennium, such tradition has been monotheistic, predominately Judeo-Christian, which philosopher Peter Kreeft, How to Destroy Western Civilization, notes, at its core has long professed that “[e]very man is an end in himself. Man is the only creature God created for his own sake. Cultures, civilizations, nations, and even religions exist for man, not man for them. And they are judged by how well they serve man, not by how well man serves them.”

This, of course, echoes Scripture: “The sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath” (Mark 2:27) which by all indications modern man has either willfully forgotten, or as more likely, has narcissistically chosen to ignore. Yet, ever more so, a higher probability rests in man choosing a god more profane, one less intransigent, certainly less creative, willing to bend the truth to fit the progressive narrative.

Every country has a civic religion and America’s civic religion, since its founding, has been wedded to Natural Law and Judeo-Christian tradition—”the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” as written in the first paragraph of the Declaration of Independence. There are people who claim they are not religious, that belief in a transcendent being is superstitious nonsense. Thus, they will argue, faith expressed in the public square is prohibited by the First Amendment to the Constitution, which is fallacious on its face—but they know that as well as anyone. Those who insist on ramming the Bible and religious dogma down everyone’s throats are cultists, evangelical bigots, Bible thumpers, primitive deplorable fools.

The enlightened secular humanists say and act as if they have no faith, and yet, their ideology, now pervasive on the progressive left, is much more a zealous faith—a zealotry which tolerates no dissent. The secularists, for the moment, have won and their zealots (the Woke Cancel Culture mob) control the language, what can and cannot be said.

Former speaker of the House of Representatives Paul Ryan said in an interview, “I remember when the gay marriage decision was handed down by the Supreme Court, the Harrisburg Patriot in Harrisburg, PA wrote an Op Ed saying, ‘We are no longer going to carry letters to the editor that oppose gay marriage because it is now hate speech.’ So, if you dissent from the orthodoxy of this secular (zealous) religion, you are a hater, a bigot, a racist—pick the term. And you are a bad person who must be silenced. And that proves my point, that their religious zealotry is a lot—talk about someone hammering a point of view down your throat—not only do they hammer it down your throat, but they also sew your mouth shut so you can’t say anything about it.”

Though they deny it, the left believes this, it is their orthodoxy, their religious faith: they are right, you are wrong, but, not only are you wrong, what you believe is hateful. Beliefs that have been around for millennia have become anathema and those who continue to believe are haters and must be silenced.

Cruelty is not limited to the barbarian. Any man, under parlous circumstances, can be cruel to other men. For the main, men are tempered by religion and a moral code, thus, such cruelty generally appears coincident with personal danger or tyranny. “And if anywhere in history masses of common and kindly men become cruel,”

Chesterton would argue, “it almost certainly does not mean that they are serving something in itself tyrannical (for why should they?). It almost certainly does mean that something that they rightly value is in peril, such as the food of their children, the chastity of their women, or the independence of their country. And when something is set before them that is not only enormously valuable, but also quite new, the sudden vision, the chance of winning it, the chance of losing it, drive them mad. It has the same effect in the moral world that the finding of gold has in the economic world. It upsets values, and creates a kind of cruel rush.”

Elsewhere, Chesterton wrote:

“When I was about seven years old I used to think the chief modern danger was a danger of over-civilisation. I am inclined to think now that the chief modern danger is that of a slow return towards barbarism…. Civilisation in the best sense merely means the full authority of the human spirit over all externals. Barbarism means the worship of those externals in their crude and unconquered state.”

As if he were writing these words in the here and now, Chesterton writes as if of the new barbarism:

“Whenever men begin to talk much and with great solemnity about the forces outside man, the note of it is barbaric. When men talk much about heredity and environment they are almost barbarians. The modern men of science are many of them almost barbarians…. For barbarians (especially the truly squalid and unhappy barbarians) are always talking about these scientific subjects from morning till night. That is why they remain squalid and unhappy; that is why they remain barbarians.”

CS Lewis wrote in The Abolition of Man, “We reduce things to mere nature in order that we may ‘conquer’ them” which serves to prove man’s desire for a profane god that can be controlled, or at the very least, modified to suit. The crisis of the West, according to Lewis, is really a crisis of reason, a crisis of reason’s ability to know nature, that at the origins of modern science, it was necessary to think of nature in quantitative—measurable and predictable—rather than qualitative terms in order to gain power over it.

“We are always conquering Nature because ‘Nature’ is the name for what we have, to some extent, conquered. The price of conquest is to treat a thing as mere Nature.” So, we reduce nature to quantity so we can control it, but whenever we do so, we lose some of nature’s quality. “Every conquest over Nature increases her domain. The stars do not become Nature till we can weigh and measure them: the soul does not become Nature till we can psychoanalyze her. The wresting of powers from Nature is also the surrendering of things to Nature.”

Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) in Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures, is even more explicit, amplifying in many ways what Lewis had only imagined:

“Less visible, but not … less disturbing, are the possibilities of self-manipulation that man has acquired. He has investigated the farthest recesses of his being, he has deciphered the components of the human being, and now he is able, so to speak, to ‘construct’ man on his own. This means that man enters the world, no longer a gift of the Creator, but as the product of our activity—and a product that can be selected according to requirements that we ourselves stipulate. In this way, the splendor of the fact that he is the image of God—the source of his dignity and of his inviolability—no longer shines upon this man; his only splendor is the power of human capabilities. Man is nothing more now than the image of man—but of what man?”

“As long as this process stops short of the final stage,” Lewis wrote, “we may well hold that the gain outweighs the loss,” because it is true that the reduction has given us significant scientific benefits in medicine and technology.

“But as soon as we take the final step of reducing our own species to the level of mere Nature, the whole process is stultified, for this time the being who stood to gain and the being who has been sacrificed are one and the same. This is one of the many instances where to carry a principle to what seems its logical conclusion produces absurdity.… it is the magician’s bargain: give up our soul, get power in return. But once our souls, that is, ourselves, have been given up, the power thus conferred will not belong to us. We shall in fact be slaves and puppets of that to which we have given our souls.”

The obvious questions one should ask are what prevents us from reducing ourselves to mere nature like the rest of things? What prevents us from reducing ourselves to mere quantity and not quality? The truth, readily available to eyes that wish to see, “if man chooses to treat himself as raw material, raw material he will be: not raw material to be manipulated, as he fondly imagined, by himself, but by mere appetite, that is, mere Nature, in the person of his de-humanized Conditioners.”

We have reduced modern man to mere quantity; no longer do we see man a rational being with an immortal soul. No more is man made in the image and likeness of his Creator, man has been quantitatively redefined, reconstituted into whatever image he desires—transgenderism and sexual orientation perhaps the most obvious— the inestimable quality of man thus reduced to subjective material value. And, sadly, that is not worth much. The elements in the human body are worth about $585. According to one source, 99% of the mass of the human body consists of six elements: oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, calcium, and phosphorus, worth approximately $576; all the other elements taken together are worth only about $9 more.

“A dogmatic belief in objective value is necessary to the very idea of a rule which is not tyranny or an obedience which is not slavery.” Ratzinger, in raising the alarm, noted how we are living in a period of great dangers, “During the past century, the possibilities available to man for dominion over matter have grown in a manner we may truly call unimaginable. But the fact that he has power over the world has also meant that man’s destructive power has reached dimensions that can sometimes make us shudder. Here, one thinks spontaneously of the threat of terrorism, this new war without national borders and without lines of battle.… this has induced even states under the rule of law to have recourse to internal systems of security similar to those that once existed only in dictatorships; and yet the feeling remains that all these precautions will never really be enough, since a completely global control is neither possible nor desirable.” He goes on to say that the truest and gravest danger at the present moment is the imbalance between technological possibilities and moral energy. “The security we all need as a presupposition of our freedom and dignity cannot ultimately be derived from technical systems of control. It can come only from the moral strength of man, and where this is lacking or insufficient, the power man has will be transformed more and more into a power of destruction.”

3.

The brutal dehumanization experienced under hard totalitarian regimes, however, is not the only form of barbarism, there is a softer, more insidious form, which—like cooking a frog by slowly turning up the heat—relies on the inattention of the masses to the soft tyranny inexorably imposed by those who would wield power over them. Zbigniew Janowski knows well from personal experience the brutality and death that comes from that particularly pernicious form of barbarism which he describes in Homo Americanus. But perhaps because of his own lived experience he also recognizes more than many in the West, especially in America, that liberal democracy can itself be as barbaric and cruel, especially without a strong moral compass to temper the powerful urges of those (Lewis’ Controllers) who would wield power.

“The absence of brutality and death in soft-totalitarianism makes it more difficult to perceive the evil of equality.” He notes that though the barbarism experienced under communism provided fertile ground for opposition and dissidents, “the other reason why dissent grew under communism was a strong sense of moral right and wrong taught by religion.” In Poland, “where the Church was strong, ideological opposition was unprecedented.”

Janowski believes the rapid decline in religiosity among Americans may be one reason why this country is well on its way to becoming a totalitarian state.

“Young Americans’ sense of right and wrong seems weak, and if it is strong, it is often limited to students who graduated from religious, predominantly Catholic, schools. One can add that the weak perception of evil may stem from the fact that Americans have not experienced the atrocities that other nations have; they don’t even know about them.”

Janowski’s point is important. Most young Americans have no clear recollection of barbarism on American soil, even worse, they have little or no understanding of it, thus, no comprehension of the barbaric underpinnings of either communism or liberal democracy. The twenty year “war” in Afghanistan has long lost any significance to those born in the twenty-first century. What precipitated it has long been forgotten, memory holed by those self-same tenured academics, judicial activists, leftist politicians, and the complicit media.

Many of those young Americans, if asked, have little awareness of or concern for the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001. Too many have been indoctrinated into believing that any mention of the radicalized Islamic terrorists who committed the heinous attacks is evidence of Islamophobia and overt racial bigotry—quite ignorant of the fact that Islam is neither race nor ethnicity, but rather, both a religion and a political system (Sharia). Islam is the name of a religion, just as Christianity, Judaism, or Buddhism; none favor or are peculiar to a particular race or ethnicity.

Josef Pieper, German Catholic philosopher, once reflecting upon the power of language, wrote, “Words convey reality” which is eminently true as far as such a brief aphorism can connote. However, precision and truth matter; words tossed carelessly together without thought convey nothing of substance.

Orwell, in his classic essay “Politics and the English Language” (1946) said as much when critiquing the dismal state of the English language. He wrote that quite apart from avoidable ugliness, two qualities were common: staleness of imagery and a lack of precision. “The writer either has a meaning and cannot express it, or he inadvertently says something else, or he is almost indifferent as to whether his words mean anything or not.”

I cannot help but add another, the writer intentionally writes in such a way as to obfuscate, confuse, deceive, or distort the message. Orwell decried the unthinking emptiness behind the rhetoric of the communist hacks of his day.

“This mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence is the most marked characteristic of modern English prose, and especially of any kind of political writing. As soon as certain topics are raised, the concrete melts into the abstract and no one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed: prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated henhouse.”

The West has gone soft and squishy. In a very real sense, the language has decayed so much it now quite completely contradicts Pieper’s otherwise sage proverb. Ideological gibberish has replaced precision in our language. Our language, as Ryszard Legutko recently wrote, has become extremely boring: a monotonous repetition of the same phrases and slogans. But, in fact, it is far worse than that, for our language has become foul, vulgar, mendacious nonsense borne out of vincible ignorance and sloth. Interestingly, as much as the tenured academics, power elites, corporate oligarchs, and propagandizing media would insist otherwise, such sins of omission and commission are not relegated solely to the unwashed, uneducated deplorables. A degree does not preclude vincible ignorance; any reasonable person could, based on encounters with teachers, students, and graduates, come to the somewhat droll conclusion that it positively guarantees it.

In recalling his years under communism, Legutko notes, “The purpose of the political language was mostly ritualistic. The language was a major tool in performing collective rituals whose aim was to build cohesion in the society and close it, both politically and mentally, within one ideological framework.”

And yet, perhaps it was Orwell who said it best, “modern writing at its worst does not consist in picking out words for the sake of their meaning and inventing images in order to make the meaning clearer. It consists in gumming together long strips of words which have already been set in order by someone else, and making the results presentable by sheer humbug. The attraction of this way of writing is that it is easy. It is easier—even quicker, once you have the habit—to say ‘In my opinion it is not an unjustifiable assumption that’ than to say ‘I think.’”

It has been said before but bears repeating, “Thinking is hard work.” As Andrew Younan, Thoughtful Theism: Redeeming Reason in an Irrational Age, explains:

“That’s why, if I can make a mean generalization, so few people do it. Believing is, in itself, pretty easy, though oftentimes the consequences of belief can be deeply challenging. Having an opinion is the easiest thing of all. Thinking is the process whereby our minds attempt to arrive at a true understanding of reality, which, if successful, leads to knowledge.” Arriving at the truth is a matter of thinking, not of feeling as so many are convinced. Younan adds, “thinking isn’t just hard work; it takes a lot of time and patience as well…. The truth of reality is not bound by your personal ability to argue or understand. Reality is what it is, independent of anyone’s competence, and the real goal, if you are an honest person, is not to win an argument but to understand the world.”

Of course, truth is, so few living today know how or bother much to think, it is far easier to sit back and leave the thinking to others. We have come to depend on experts, to trust the “science” without question. We forget or have forgotten to trust in our innate ability to reason, to think for ourselves.

“There’s a lot more to a human being than meets the eye, and someone can be brilliant in one area and make enormous mistakes in reasoning or leaps of logic in another area. This includes your parents, your pastor, and all of your teachers.”

Education (government/public) no longer educates, no longer trains minds to think and to reason, it indoctrinates, its purpose to produce compliant drones incapable of independent thought. Younan concludes with this advice to young students, “This has everything to do with you, and you have to trust that your own mind is capable of working through every side and of finding an answer if there is an answer that can be found” which, somewhat paradoxically, leads to a final thought: no one reads anymore. No one reads for the same reason they no longer think: reading requires thinking and both demand strenuous mental exercise. We have grown complacent and comfortable in our ignorance. They call it the boob tube for a reason. As long as we have three hots and a cot and a smartphone to play Candy Crush we are smugly satisfied.

There is a prevailing mythos with respect to higher education which presents degreed individuals as in the majority. This is, at best an enormous overstatement. According to 2019 census data, the percentage of individuals 25-44 years old having earned an undergraduate or post-graduate degree was 37.1 percent for the United States. Broken down by state or district, the indicators represent where college degree holders live, not where they were educated. As might be expected, the District of Columbia holds top spot with 70.4%, Mississippi takes the bottom spot at 22.7%. Thirty-one states are below the national average, East Coast states are among the highest, ranging between 40-52%.

There are three important takeaways from this: first, the preponderance, almost two-thirds, of those within the reported age group are not college educated and live for the most part somewhere between the two dense urban coasts; second, if the output of the academy is predominantly socialist cant, then what does that say for the ideological mindset of the denizens of the District of Columbia; and third, given the underwhelming product of the overwhelming majority of academic institutions in this country, one would be well within their rights to ask who is the more ignorant? Ask a farmer in flyover country who was the first president of the United States and odds are good his answer will be George Washington. Ask a student or a recent graduate the same question and the odds of a correct answer are no more than one in ten, if that. The truth is education has become a tool for inculcating the progressive ideology into the minds and hearts of our youth.

Orwell called it thoughtcrime: politically unorthodox thoughts, such as unspoken beliefs and doubts that contradict the tenets of the dominant ideology; thus, the government controlled the speech, the actions, and the thoughts of its citizens.

In Homo Americanus, Janowski provides further insight. “The danger of the new dialectical thinking is that we no longer operate in the realm of facts, physical reality, established social norms, shared moral and intellectual assumptions, or even a common understanding of the normal and abnormal, sane and insane, but we must operate in the realm of someone else’s mental universe, which we are forced to ‘respect.’ … My perception of the world and, therefore, my existence is a psychological onslaught of someone’s perception of the same world, and my crime lies in that I do not recognize that someone else feels differently.”

The Venerable Fulton J. Sheen wrote in Communism and the Conscience of the West (1948) of the decline of historical liberalism and the rise of the antireligious spirit:

“It is characteristic of any decaying civilization that the great masses of the people are unconscious of the tragedy. Humanity in a crisis is generally insensitive to the gravity of the times in which it lives. Men do not want to believe their own times are wicked, partly because it involves too much self-accusation and principally because they have no standards outside of themselves in which to measure their times. … The tragedy is not that the hairs of our civilization are gray; it is rather that we fail to see that they are.”

He went on, citing Reinhold Niebuhr, “Nothing is more calculated to deceive men in regard to the nature of life than a civilization whose cement of social cohesion consists of the means of production and consumption.”

Such calculated deception is now evident in most of the West. Nearly two decades earlier and ninety years in the past, Sheen observed in Old Errors and New Labels (1931), “[t]here has sprung up a disturbing indifference to truth, and a tendency to regard the useful as the true, and the impractical as the false. The man who can make up his mind when proofs are presented to him is looked upon as a bigot, and the man who ignores proofs and the search for truth is looked upon as broadminded and tolerant.”

4.

At its core, barbarism sees the world as through a carnival fun-house mirror—without the fun part, dark, distorted and ugly—much as O’Brien tells Winston in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four:

“The old civilizations claimed that they were founded on love and justice. Ours is founded upon hatred. In our world there will be no emotions except fear, rage, triumph, and self-abasement. Everything we shall destroy—everything. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.”

The core of every totalitarian ideology, be it Marxism, socialism, communism, fascism, or any variant ism rests on the idea that there is no afterlife. As John Lennon so fatuously put it, “no hell, no heaven, no religion, too.” Without the promise of life everlasting, there can be no incentive to be obedient, to behave rationally or morally. Janowski, referring to Darkness at Noon, Arthur Koestler’s fictionalized account of the Stalinist trials and confessions, reinforces O’Brien’s declaration:

“Fear, and fear only, can make people obey in this life. If you rebel, you will be killed, but before we kill you, we will give you an option. You can make a sacrifice for the sake of others—let your death be a warning to others not to rebel. … Your confession and death may even be considered acts of sacrifice for the sake of humanity. Otherwise, you will die uselessly.”

This then is the true face, or the three faces of barbarism, of true evil. In Greek mythology, Cerberus, described most often as a three-headed dog with a serpent’s tail, guards the gates of hell. “Like the meanest junkyard dog imaginable, he lunges to devour anyone who tries to escape.” What do his three heads represent? Power, pride, and prejudice.

Power seems to be an integral part of our humanity. Dwight Longenecker, Immortal Combat: Confronting the Heart of Darkness, describes power as an innate characteristic of man’s free will.

“It is not just that I have power. It feels like I am power, and I assume that the exercise of my power is justified. This is a basic instinct. It is a key to survival. It is unquestioned. I, therefore, see nothing wrong with exercising my power to its greatest extent. To do as I please is as elementary as the need to breathe, eat, and drink, to procreate and live. It never once occurs to me that my will should be curtailed and my power limited in any way. Furthermore, because I have the power to choose, my choice must be the right choice. I must be right. There can be no other option.”

Rational minds can immediately see how such an instinctual human attribute can lead and has led to tragic, too often barbaric abuses of power.

“The total conviction that I am right is the heart of pride, and pride is the second head of the hell hound Cerberus.” Pride is not vanity or arrogance, these are only masks. “Real pride is the overwhelming, underlying, unshakeable, unchallenged, unquestioned, total, and complete conviction that I am right.… Pride is the total, complete, foundational assumption, before all else and above all else, that I am right, that my choices are right, that my beliefs are right, that my decisions are right, that everything I do is right. This complete conviction that I am right is deeply rooted in my character. … Furthermore, power and pride are so basic and deeply embedded in the foundations of who we are that we cannot see them. Power and pride seem like part of the genetic code.… They are deep down. They are invisible.”

“This invisibility of power and pride reveals the third head of Cerberus: prejudice. Prejudice is intertwined with pride and power. To have a prejudice is to prejudge. It means our perceptions are biased: we view the world through tinted glasses. We do not judge objectively, but rather, we approach life’s challenges with our ideas and opinions preloaded. Power allows us to choose, and pride assumes that our choice was the right choice. Therefore, everything in life, from the lunch menu to the news headlines, comes to us through our preexisting assumptions that we have chosen well, that we are right.”

Overweening power, pride, and prejudice are the hallmarks of tyrants, oligarchs, autocrats, and totalitarian regimes. Cerberus may have been a Greek myth, but his heads are with us still. We are living in barbaric times, where the leviathan state threatens to consume the West, including, most noticeably, America. Author Ayn Rand once warned, “We are fast approaching the stage of the ultimate inversion: the stage where the government is free to do anything it pleases, while the citizens may act only by permission, which is the stage of the darkest periods of human history, the stage of rule by brute force.” That stage has arrived.

Ronald Reagan, the 40th president of the United States, famously quipped that “The most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.’” The American people have forgotten his admonition. They have forgotten because they have become complacent in their abundance and the comfort such abundance affords them. They have been so comfortable for such a very long time that far too many no longer value liberty and freedom in the way Americans once did, rather, far too many of the American people give greater weight to safety and security, or at least the illusion of it, more than they value freedom and liberty. And the government has taken notice. Ask yourself, with every government overreach, every authoritarian diktat, every tyranny imposed, every right disposed, what is the government’s justification for it? The answer is ironically, for the greater good, for your health and safety, etc., etc.

One example will serve to illustrate the growing tyranny of the state. There is an alarming motion, put forth by the state media and public health experts, to identify and separate the unvaccinated from the vaccinated, to deny services and to isolate those who have chosen not be receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Some pundits have gone so far as to say the unvaccinated deserve to die. At the very least, the unvaccinated should be identified (Star of David?) and, I suppose, cry out “Unclean, unclean” whenever in public. Now, where have I seen that before…

“The leper who has the disease shall wear torn clothes and let the hair of his head hang loose, and he shall cover his upper lip and cry, ‘Unclean, unclean.’ He shall remain unclean as long as he has the disease; he is unclean; he shall dwell alone in a habitation outside the camp” (Leviticus 13:45-46).

The founders of the American idea thought they had designed a limited government subservient to the will of the people. John Adams, the first vice-president and second president, famously wrote, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” The barbarians are inside the gates, and they are neither moral nor religious, they are greedy for power and will do what it takes to obtain and maintain their tyranny and control.

What is less clear to the American people is who is in control. One thing is becoming increasingly obvious: it is not the three branches enshrined in the Constitution. The true power resides in the administrative state, the uncontrollable, unaccountable, unelected bureaucratic ministries that have come to regulate every aspect of American life. And what largesse the bureaucrats provide, the bureaucrats will take away, or as Gerald R. Ford, the 40th vice-president and 38th president, admonished:

“A government big enough to give you everything you want is a government big enough to take from you everything you have.” But, it is the words of Benjamin Franklin, when asked what form of government the founders had created, which should be well remembered, “A republic… if you can keep it.”

Seventy-three years ago, Fulton Sheen saw America for what it was and what it was yet to be. “America, it is said, is suffering from intolerance. It is not. It is suffering from tolerance: tolerance of right and wrong, truth and error, virtue and evil, Christ and chaos. Our country is not nearly so much overrun with the bigoted as it is overrun with the broad-minded. The man who can make up his mind in an orderly way, as a man might make up his bed, is called a bigot; but a man who cannot make up his mind, any more than he can make up for lost time, is called tolerant and broad-minded.

“A bigoted man is one who refuses to accept a reason for anything; a broad-minded man is one who will accept anything for a reason — providing it is not a good reason. It is true that there is a demand for precision, exactness, and definiteness, but it is only for precision in scientific measurement, not in logic.”

Americans are suffering from the severest form of intellectual anorexia. We are told we are intellectually too fat; we are not, we are too thin. We have enslaved our minds, our hearts, and our spirits on a diet of free and easy. It was once said of America that its people cast a big shadow. No more. We have become too thin to cast any shadow at all. The worst of it is no one cares. And that is the surest sign of death and the onset of a new age of barbarism.

Deacon Chuck Lanham is a Catholic author, theologian and philosopher, a jack-of-all-trades like his father (though far from a master of anything) and a servant of God. He is the author of The Voices of God: Hearing God in the Silence, Echoes of Love: Effervescent Memories, and four volumes of Collected Essays on religion, faith, morality, theology, and philosophy.

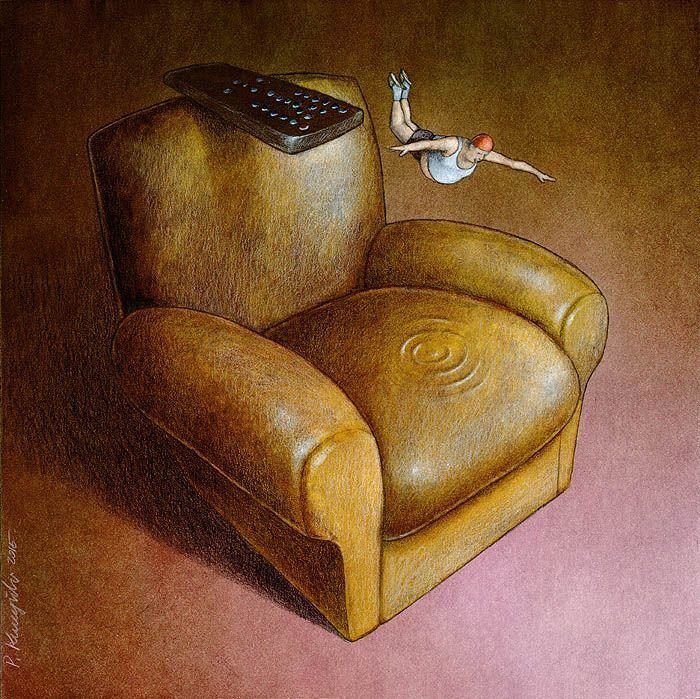

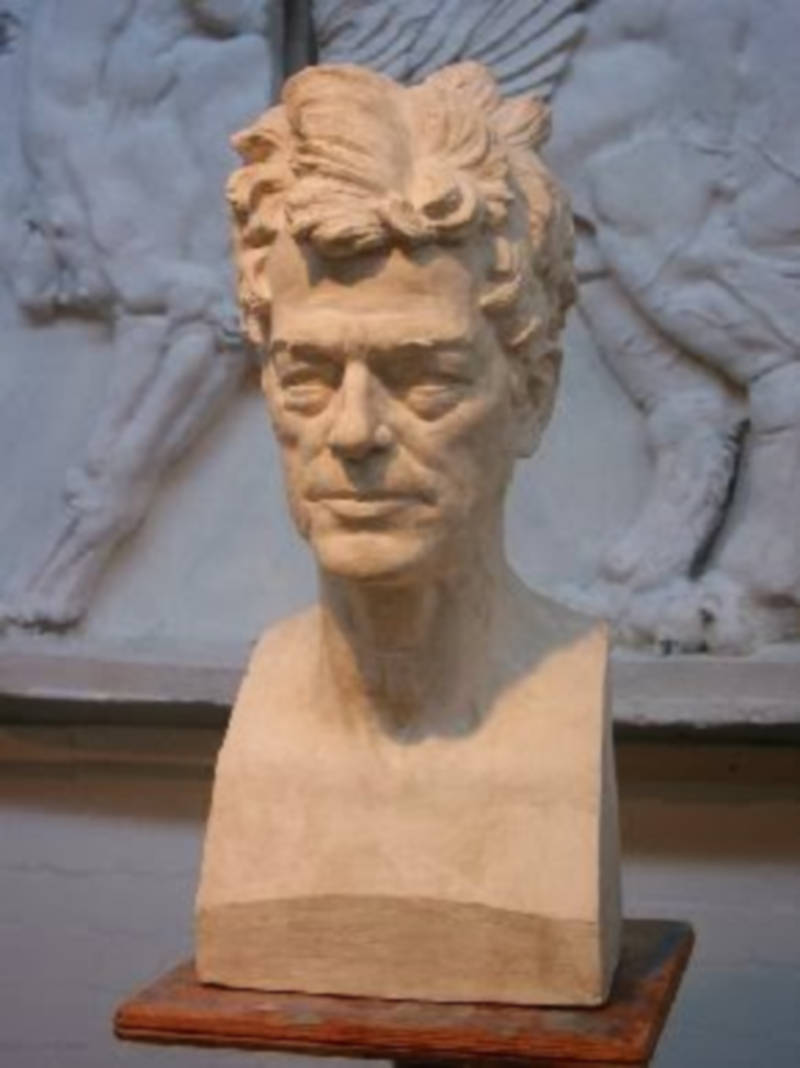

The featured image shows, “TV Sport,” by Pawel Kuczynski; painted in 2017.