Free speech and freedom of expression are often assumed to be inherent qualities of being a modern human being. However, modern life is also very much aligned with technology, where freedom has very limited currency, because it gets in the way of the larger project of the entire Internet which is the establishment of vast communities that, hive-like, depend upon like-mindedness. Such conformity is termed, “community standards,” which are policed by various rules and regulations. Transgression of these “laws” brings punishment. either mild or severe.

But the Internet is also a marketplace, where things are bought and sold, and where thousands, if not millions, of people have established flourishing careers. Here, the question of freedom seems entirely irrelevant, since all manner of things can be bought and sold – even the most heinous (like pornography of the worst sort and human trafficking). There is no internal policing here, and thus no limit to what can be bought and sold.

Access to the Internet, whether for information, communication or commerce, is controlled by platforms and their owners. And those who own and control these platforms also own and control communities and the “standards” which govern them. At the same time, these platforms provide the means for effective commerce. For example, most people use the platform known as, Facebook, for communication – while most other people use Facebook to sell things. This dual function makes Facebook both a communications company and a service-provider for commerce.

But notice what takes place in this dynamic – suddenly, Facebook is both a policing agency which cannot allow any sort of disruption of the harmony that it is trying to establish within its community of the like-minded – while also being an open marketplace, in which it also profitably participates by selling ads. Thus, where does Facebook’s allegiance lie? To the community, or to the marketplace? This question, in fact, burdens all other platform owners also, such as, Twitter, Youtube, Google, Instagram, and so forth.

What happens when the community feels disrupted and complains to the platform owner to do something about the disrupter who happens to be using the platform for commerce? As has been happening rather regularly, the platform heeds the community and exiles the disrupter who has no recourse for appeal and everything that he/she has built is immediately shut down.

This is known as a “deplatforming campaign,” where the outraged bombard service platforms with complaining emails and messages asking that the disrupter’s very presence be entirely removed. Does the platform owner do nothing and continue to profit from the disrupter’s commerce? Or, does the platform obey the will of the outraged community – and drive the disrupter from the platform forever?

Welcome to the Cancel Culture – where what you say may not just get you banned from using the largest services on the Internet, but may also get you banned from using essential services like banking and credit cards – just because someone did not like what you said online. This modern-day version of exile is known as, “deplatforming.”

It is a dire problem, affecting thousands of people, many of whom have lost all ability to earn a living. Suddenly, the question of freedom takes on a far grimmer aspect, in that it starkly shows that for some, being deprived of freedom means not only the inability to speak online – but even being deprived of money. In the great juggernaut of mega tech-companies that own the Internet, the deplatformed individual instantly becomes a non-entity, a non-person, who is also denied financial services, such as, banking and credit cards.

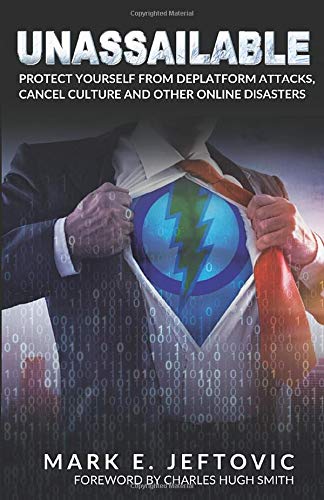

Given the fact that cancel culture is only growing, in which outrage is the new morality, it is indeed timely that Mark E. Jeftovic has written, Unassailable. Defend Yourself From Deplatform Attacks, Cancel Culture & Other Online Disasters. Jeftovic is certainly the right person to be writing this book, as he runs a technology company himself, in Toronto, Canada, and is a current Director of the Internet Society, Canada Chapter. So, the wisdom that he imparts is not theoretical, but solid and practical.

Therefore, this book is filled with valuable insights about the problem of deplatforming – but more importantly it also offers real and viable solutions to arm the ordinary individual with strategies to survive and thrive online. This is especially crucial for people who make a living online. Jeftovic lays out his plan clearly: “This book is for anybody who earns their living online. While primarily it is for content creators, many of the principles in this book can be used by any business that relies heavily on their internet presence, and as such must take measures to remain online at all times.”

For those who might imagine that this all some tempest in a teapot and far beyond their own interaction with the world online, Jeftovic has this to say: “Even if you are a content creator who assumes nothing you say is controversial enough to attract a deplatforming campaign, bear in mind that what seems reasonable today may be considered beyond the pale tomorrow.”

The book begins with a Foreward by Charles Hugh Smith, which is a chilling but spirited summary of what is truly at stake: “Societies around the world are experiencing unprecedented cultural purges of ideas and narratives that challenge the status quo. In some nations, this purge is managed by the central government, China being a leading example. In the developed Western nations, this purge is being conducted by private for-profit technology platforms that function as quasi-monopolies in Internet search, video and advertising (Google) and social media (Facebook and Twitter).”

These tech giants are now all-powerful kingdoms who control their realms and their borders very effectively; and their decisions are final and without any due recourse: “A content creator banned by a tech platform has no rights or recourse: the platform is not obligated to identify the “crime” that supposedly violated their User Agreement or present evidence in support of this accusation. The banned user has no means to contest the ‘conviction’ or the ‘sentence.’” Thought criminals are therefore made invisible instantly.

This silencing, or rather erasure, of people is now on-going and persistent practice because these “tech platforms wield extra-legal powers that are impervious to conventional government protections of civil liberties. (Those who attempt to sue these corporations face legal teams larger than those serving government agencies.) Users agree to open-ended Terms of Service that the corporations can interpret however they please, without any transparent process of appeal or redress.”

In effect, if people do not know how to protect themselves, they will always be victims online. It is this protection through knowledge that Jeftovic offers – and his book is the very blueprint for being empowered online in the years ahead.

The book itself is divided into two parts. The first is historical in nature and is therefore entitled, “The Battle for Narrative Control.” Here, Jeftovic provides context for the “culture war” currently being fought on all fronts by those who want to make sure that people only have access to a certain kind of “truth;” that the harmony of like-mindedness is rigorously maintained; and that freedom means absolute conformity. Such hive-mindedness can only result in a society that is “less intolerant and more inclusive with each successive generation.”

In fact, all of us are now used to the conditions of groupthink, because we respond in the prescribed manner whenever we encounter certain “trigger-words.” Jeftovic warns: “The real threats today have names like “the greater good”, “the science is settled”, “that’s a conspiracy theory” and any other variation on a theme that some people feel it’s within their purview to decide what ideas are acceptable for everybody else, and more perniciously, that any disagreement is illegitimate and not permissible.”

Part II is entitled, “What You Do About It,” and it is an honest and highly useful blueprint to entirely and fully own your own means of production (to use a convenient Marxist phrase). If you rely solely on the means of production provided by the platforms of the tech-giants, you will always be in danger of being silenced, unpersoned, and financially destroyed.

Jeftovic then proceeds a give step-by-step, and easy-to-follow methodology, through which you can “own the race-course,” as he puts it. He covers all the essentials that are necessary to ensure your financial and even ideological survival on the Internet. These include: owning and promoting your own brand; the best webhosting; how to do blogs the right way; how to engage with discussion forums; how to get the right kind of email service; how to podcast; how to buy and sell online; avoiding bad revenue models and using good revenue models; how to get on alternative platforms, and much else besides.

Since, Part II is really a how-to instruction manual, it would be unfair to summarize what Jeftovic teaches, for most of it is proprietorial information that will be available to those who purchase this book. To do otherwise would be stealing his commercial thunder, as it were. For those that truly want to use the Internet as a means to exchange ideas and to enter into profitable commerce, then Unassailable truly is an essential and necessary vademecum.

In one of his thought-pieces at the very end of the book, Jeftovic has this to say: “Do you really want to live in a world where people sever business and personal relationships because a literal flash mob demands it? Where mobs get to pick and choose who you are allowed to associate with?”

How will you answer these crucial questions in this society where outrage is a valuable commodity? Perhaps, the greatest way to thumb one’s nose at tech-tyranny is to survive and to prosper, no matter what the tech-giants throw our way. Jeftovic has likely written a revolutionary manifesto about winning freedom in this tech Dark Age.

The image shows, “The Gathering” by the Swedish illustrator Simon Stålenhag, painted in 2015.