Some months ago, I wrote an essay on the Russia-Ukraine war, “The Russia-Ukraine Conflict and the Turmoil of Our Times,” where I laid out why I could not accept the explanation of that event as being due to ‘mad bad Vlad, and his imperialist globalist aspirations. I also indicated that I took no joy in reaching my position. This remains the case. Not only was my interpretation of the war one more thing that placed me in the camp of what the ideas-brokers and majority of “well-educated” people in the West now label as conspiracy theorists, but, in this case, I was also a Putin stooge. So, my inability to accept the “truth” that so many around me knew without any doubt to be the case about the motives, intentions, historical background and moral character of President Vladimir Putin means that I really am an idiot. I have certainly made the case here in the Postil that I see the Western elite as driven by imbecilic ideas, but it is possible that all the political philosophy and history I have read have culminated in me sniveling and driveling at my desk, while whistling “How sweet to be an idiot.”

Idiot and stooge though I might be, as I made clear in that essay, my position is not based on moral imperatives, which are meaningless to billions around the globe, but on fundamental tenets of International Politics and Comparative Politics. In the case of the former, one fundamental tenet requires that one should heed the “interests” of the respective parties involved in any geopolitical/ diplomatic dispute—and by “interest” I primarily mean the assumptions and priorities that guide the behaviour of disputants. In the case of Comparative Politics (a discipline that commences with Aristotle), one must begin by identifying the different historical and cultural conditions which inform the institutional possibilities and circumstances (and hence types of crises) of a polity and its people.

In a subsequent piece, I also emphasized that narratives and points of view invariably depend upon what I call “prime facts and factors.” Mostly, though not always, prime facts are “assumptions”—the kind of things “everybody knows.” Since Socrates, philosophers have recognized the need to be wary of what everybody “knows”—and though I think Plato’s Socrates might have been more charitable to instinctive knowledge, which is the basis for a healthy kind of commonsense, when it comes to opinions that derive from information that has invariably been modulated to suit the interests, perspectives, and priorities of the narrators, we are well advised to adopt the kind of skepticism we associate with Socrates.

Mr. Kerr’s essay, “The Enemy of My Enemy is My Friend,” unfortunately is not one that shows much care for the fundamentals of International Politics, Comparative Politics, or Socratic skepticism. It is driven by moral outrage, based upon information that he holds to be not only accurate about but also particularly germane to the war. Those parts of the essay I do agree with—e.g., about the role of the Soviets in the Ukraine—I don’t see as particularly relevant to the diplomatic crisis that led to the current war.

I will return again to the problem of taking morality as an adequate guide to understanding and dealing with international conflicts, but here I shall just make the general point that while there are plenty of people (today possibly the majority who teach IP or IR in the West) who do normative International Politics/Relations, the problem with that approach is that it distorts our understanding of international conflict, by overly simplifying, or even dispensing with, the need to identify the contingent causes (because it is _____________. Fill in any name you like, for any conflict you like). But one has only to observe US foreign policy since the end of the Second World War to see that moral consistency becomes impossible in International Relations because of the strategic necessity of building alliances. Which is to say, that normative driven claims in IR quickly become disclosed as haphazard, and hypocritical—which is how Russia, China, and many other nations today see the US.

In my previous essay on the war, I also made it clear that my conclusions came from a number of sources: I found that the mainstream media either told outright lies or distorted the event by omitting information that was intrinsic to Russia’s invasion. The mainstream media were often critical of “neocons” on the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, but have often provided a wall of silence, and tacit or even outright support when it comes to US arming and training rebels in regimes deemed to be dangerous to US interests, and stirring up chaos in regions harmful to their interests. The media have been completely complicit through their silence on, or “framing of, such events as the US’s training and support for Chechen rebels in their war against Russia in the 1990s, the opposition to Gadhafi, and, the Free Syrian Army, whose factions included Jabhat al-Nusra (Al Qaeda’s franchise in Syria), against President Sadat.

The present neocon “line” on Russia, like that of the mainstream media, is built upon political norms that are fair enough in the West (after we allow for all the mud and blood of conquest, wars, enslavement, etc. that are the typical conditions and contingencies enabling nation founding), but which defy the possibilities that were open to any Russian hegemonic aspirants in the breakup of the Soviet Union. The US-West track record in Afghanistan and Iraq leaves them with no credibility—the Taliban are back, and Iraq is a Shia state.

Yet the media which was once at least often prepared to denounce neocons and Bushites, sees no problem with supporting an all-out proxy war and being utterly uncritical of a reckless regime that has taken the country from a civil war of its own making (albeit with US help), calling for ever more military support and Western involvement against Russia. If Bushite neocons led the charge in Iraq and Afghanistan, it was Obama-ite liberal imperialists, whose enthusiasm for the Arab Spring has helped create the chaos in Libya and Syria. Both were driven by the same delusion about democratic regimes taking off in the region and making all these Arab states one big happy McDonalds-munching family. So now it is the scions of neocon and liberal imperialism who write about how Putin’s demise would liberate Ukraine, Russia, and wherever else they can think of as bearing any connection to their dreams of US hegemony. More generally, and just like the wise guys advising whichever ‘commander in chief’ was at the helm of the latest debacle of creating a liberal democratic global order, the mainstream media seem to have no interest in understanding, or being concerned with, the historical and cultural contingencies relevant for making sense of anyone’s—including Putin’s—rise to power in a far off land, or the support-base of regimes they do not like.

I do not think these points irrelevant when I see the same groups of people so swift to weigh in on the conflict in the Ukraine.

While I think Regan had good grounds to plot the demise of the Soviet Union, as well as the good fortune to do it, the USSR of yesterday is not the Russia of today—and the widely held belief that Russia today has the same imperial aspirations as the USSR is at best a conjecture which I do not share—at worst it is a fabulation to shore up a political elite aspiring for global domination by trying to equip and maintain an international military machine on standing reserve.

Were the Western elite a more intellectually formidable and politically astute group that had brought greater social concord and prosperity to the people of its nations, then it would not need to bully and silence its critics, and it certainly would not fear that Russian misinformation would fracture the good society it had contributed to. But the West is a mess and Western elite have contributed significantly to this mess. They do not deserve their status nor positions, for the institutions of ideas-making and circulation from higher education to the media, to the political parties, and the heads and managers and HR officers of corporations who dictate the norms that we must obey—are as spiritually broken as they are intellectually vapid.

Forgive me this lengthy setting up of my critique of Mr. Kerr’s essay, but with any event and any author there is often a lot of background that is tacitly assumed; and hence it is a good idea to bring some of the background assumptions to light. Ultimately Mr. Kerr’s argument is that of the mainstream and the neocons—and it can be summed up as the “it’s Putin, stupid” argument; plus, anyone who does not agree with this is not only stupid, but a Putin stooge.

Given the tone of his essay—don’t get me wrong, I enjoy satire and polemic as much as I enjoy watching Tyson Fury; the issue is whether the punches land—Mr. Kerr indicates that he is completely committed to his view of things. So, I do not write this essay in the hope that Mr. Kerr will change his mind—and if I seem acerbic, let me say that I have close friends who think like him. I would be happy if ever we met to discuss this further over a beer or wine, or, dare I say, vodka. But unlike Mr. Kerr, as much as I think the mainstream Western media and elite a pitiful shamble leading us into the end of a civilization and all the catastrophe that that entails, my exasperation is at their pride and inability to think with any clarity about serious things in any other than a simplistic self-serving manner.

In any case, and in response to Mr. Kerr’s accusation that if one is not for Zelensky one is a stooge/ traitor/ moral reprobate, let me state that I have no stake in what I think about this war—I am trying to make sense of what is going on and what it means. I write for those wanting to understand a little better what is going on, and who, like me, find the dominant “line” unconvincing. I would like to think that I bring to the matter a lifetime of studying Politics and Philosophy and teaching European Intellectual History and Political Science—but I might be rubbish at all that stuff; and even if I am not always rubbish, I might be way wrong on this one. Mr. Kerr, though, does not consider that he might have got things wrong; and for him it is all very black and white.

In the first instance, I find the very pitch of the problem, as presented by Mr. Kerr, problematic—he is writing his essay against “those who oppose Western liberal democracy, or see it as no longer working, [and who] tend to see either Russia (or the former Soviet Union) and/or Putin in a soterial sense.” Anyone who has read my essays will know that I do not “oppose” Western liberal democracy—I mourn its demise, and write in search of like-minded opponents of those who want to restore the value of politics as brokering between antagonistic interests, which can only be achieved if one accepts that the viability of liberal democratic institutions requires respecting the procedures that hold a civic culture together. Respect for the political culture matter more than the results; which is to say that the institutions can only function, if the political culture is healthy.

The extent of the sickness of the political culture of the West was made evident to me the day after the election result in 2016 in the US was announced, when mass demonstrations took place, followed by calls by public figures—some journalists, and entertainers (Johnny Depp, Madonna)—for Mr. Trump’s assassination. These demonstrations and calls, along with the behaviour of journalists and academics, were all symptomatic of a broken political culture. Pretending this was of little consequence is simply to hide one’s head in the sand. I say this because while Mr. Kerr and I agree about the ill health of the political culture of the West, I don’t think his analysis takes this seriously enough: had he done so he might have considered why this is particularly relevant to the kind of military interventions that the West might engage in and what they might mean. So, yes, I confess—I belong to the camp that sees Western liberal democracy as “no longer working.”

But I fail to see why thinking this would make me or anybody else see Putin as a “saviour.” I do not need to argue on behalf of Mr. Dugin, though I am very grateful that the Postil sees fit to present his position. It is the position of someone with a set of political commitments and priorities that inevitably has little appeal to most people in the West, including me. But Mr. Dugin is writing from another set of concerns and for another constituency.

It is very important when doing International Relations to understand the objectives, priorities and values of a rival or enemy. I think Russia may have always been a potential rival with the European powers; at least in certain regions; and, of course, the Poles and the Baltic states have legitimate historical grievances with Russia, which makes sense for them to fashion stronger ties with the West. But Russia did not have to be our enemy: through various decisions and legislation—including the Magnitsky Act of 2012 and the support for the Ukraine coup in 2014—the West has made it so. The idea that Mr. Dugin is the real brains behind Putin is another piece of fiction that seems to have been enthusiastically embraced by those who have little interest with the day-to-day problems that face every (including the Russian) president. His daily problems are not mine; nor are they the problems of anyone in the West. So, unlike Mr. Kerr, I have no idea who he is talking about when he speaks of those opposing the interpretation that “it’s Putin, stupid” argument and those critical of the West’s role in this war seeing Putin as a saviour.

Mr. Kerr also writes that:

One of the surprising things about this conflict is that Putin, for it is by all accounts more Putin’s conflict than Russia’s, has found an odd group of diametrically opposed groups, largely amongst the extreme wings of the Western political spectrum: the far right (anti-Americanism in Europe), and the far left (anti-capitalists). Both support him and his conflict, legitimately enough, in what they see as their own best interest, and to serve their own goals.

Apart from my dissatisfaction with the blithe aside “for it is by all accounts more Putin’s conflict rather than Russia’s” (No—the accounts that say this are far from “all;” but when such a wild—dare I say stupid—opinion is cited as a fact that everybody knows, I find myself exasperated by the “build” of the “argument”)—the word “extreme” is a term thrown about a lot today. It suggests a middle/moderate centre that I fail to see now existing in the West: is thinking the overturning of Roe vs. Wade an “extreme” or moderate decision? Is speaking out against BLM “extreme,” or not going along with high target carbon reduction schemes, opposing vaccine mandates, or questioning whether a new kind of vaccine might not yet be ready for market because all the usual protocols of testing have been waived—“extreme”? This is not a polemical point; it is simply to acknowledge that there is no centre anymore—and that the use of the word “extreme” is just one more rhetorical device to denigrate people with whom one disagrees.

For my part, I do not identity as right or left; for the main political problems of modern liberal democracies requires the balancing of interests in the light of market and state powers, a task that is impossible if one is ideologically beholden. Though the West is sinking precisely because ideology has driven out the kind of dispassionate and disinterested investigations that might better inform policy and legislation, and have turned politics into a contestation over whose values may be used to enforce what people think, say and do. The very terms left and right tend to be useless, if one genuinely wants to clarify the disputations of our time. George Galloway and Russel Brand, to take just two, were once easy to identify as leftists; but now they find common cause with a large audience that are politically populist and socially somewhat (though mostly only somewhat—they believe in freedom of speech) conservative, but not extremist; unless being an extremist is thinking 1776 a historical moment signifying a political promise to be venerated, and 1619 an ideological source of division and social break up.

What tends to unite a very disparate group of people who do not see this war as “Putin’s war” is not their extremism, but their criticism of corporate/statist/globalism, and the way in which this war has yet again been used to galvanize narrative uniformity, to isolate and punish those who do not agree with the official line—Mr. Kerr does not seem to mind because it is the same line as that of Mr. Kerr’s and he is deeply disappointed that the Postil publishes authors who see things differently. Today an extremist is someone who opposes legislation which limits freedom of information and increases censorship (the justification offered by those doing the censoring is that they are protecting the population from dangerous misinformation), and one who objects to key decisions—such as engaging in a proxy war—being introduced without such decisions becoming a matter to be resolved through the democratic process: in Australia both political parties, when in government, have sent tax payers money to help this “fight for freedom.”

As with so many other topics, the media and academia have become megaphones of state policy that supports a “liberal”/ progressive international order. That order offers plenty of work for those who scout out those who deviate from the program. For them it is obvious that only extremists, moral pariahs and conspiracy theorists would be so ignorant and/or dangerous that they would dare disagree with the dictate of the hours: whether it be how to defeat the climate catastrophe, prevent racism, or hatred towards gays and trans people, or drag queens reading to kids in libraries, or prevent a virus that could wipe out the entire world’s population, or send weapons to Ukrainians wanting to defend themselves against Russian troops who have entered the country to defend a substantial portion of the country who are ethnically, historically, economically allied with Russia, and who never supported the coup against a President who was not prepared to throw in the country’s lot with Europe at the expense of those connections. But, heck, for the progressive, these issues are pretty much all the same—they are one more brick in a totalitarian “liberal”-globalist-international-liberal-progressive order, led by a global technocratic corporatist elite. This order, like the various crises that are enabling it, is predicated upon the elimination of all political dissent; which is, to say, the elimination of freedom speech.

I do not think Mr. Kerr should not have his say. But I am not convinced by the arguments and opinions which ebb and flow out of each other, as if he is the voice of reason, and anyone else is an extremist or idiot. I will leave aside the lengthy historical account that Mr. Kerr goes into—a fair portion of which explains why non-first Russian language Ukrainians hate Russians—something I do think is largely ignored in Mr. Putin’s speeches—and hence why so many in the West of Ukraine supported the Maidan. I said in my earlier essay, if I were part of that ethnic group, I would have probably supported the coup and regarded Stepan Bandera as a hero, maybe even have joined the Azov Battalion—but Mr. Kerr does not discuss the importance of Bandera, or the Azov Battalion and other ethnic militia and their significance in fueling the civil war that began in 2014, with any seriousness. He writes:

One of Putin’s primary casus belli is the alleged treatment (“genocide”) of Russians and slavs by the (Western) Ukrainians, slandered with the stock trope “nazi”. While the Ukraine’s treatment of ethnic minorities may not be perfect, its record is certainly no worse than Russia’s (and which abolished the representative body, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People in 2014 and outlawed it in 2016 allegedly due to “the use of propaganda of aggression and hatred towards Russia, inciting ethnic nationalism and extremism in society.”

These sentences are a good example of why I think analysing international conflicts in purely moral terms quickly degenerates into partisanship where one downplays misdemeanours that belong to one’s party as one concentrates on those of the opponent. The stock trope of the Nazis is very pertinent when one looks at the history and even insignia of the anti-Russian Ukrainian ethnic ultra-nationalist groups. But then again my argument, and indeed most of those I listen to and read, are not making an argument about the moral purity of the Russian people, or nation, or President—but about why Russia has invaded Ukraine. To separate Russia’s invasion from the persecution, and large scale killing of ethnic Russian Ukrainians is as disingenuous as describing this as not being “perfect” “treatment” by the Ukrainian government. How many ethnically dead Russian-first-language-Ukrainians would it take for Mr. Kerr to register their existence on his moral radar?

As for Russia’s treatment of its minorities, why or what does that have to do with the issue of this war? This, though, is yet another reason for not trying to use merely moral means for mediating between disputes. The issue is that there has been a civil war, with one side having strong ties to Russia, in a region of major strategic interest to Russia; and Russia has acted in a way that pretty well any state in similar circumstances would have acted. It has never occurred to me that the USA was not acting in its own strategic interests when it demanded that the USSR desist from deploying missiles on Cuban soil. Trying to determine who had the moral right in the Cuban crisis does not strike me as very helpful: Immanuel Kant, Peter Singer, Derek Parfit, Michel Foucault, or whichever other moral philosopher you may want to call upon might or might not agree with what Russia has done—but as they don’t agree with each other on anything, I don’t think they are going to be of much help here. But why the US responded as it did, differs little from why Russia has responded as it has to NATO training Ukrainian soldiers and fanning the flames of regional instability to secure its own strategic interests.

As for the plight of the Russian ethnic Ukrainians to whom Mr. Kerr gives such short shrift, he seems to imply that it is their own fault anyway for being there, or at least the fault of their forefathers. He correctly points out that Stalin had engaged in repopulation. But so what? The people living there now have interests, and those interests include speaking in their own tongue, which is to say having schools and media that express their identity and concerns, and resisting people who are threatening their way of life as well as their very life. Saying this does not morally “justify” Russia’s invasion—very little human beings do can be traced back to moral origins. And, to repeat, pitching an argument about “peoples” and “nations” as if one were engaging in a moral debate simply does not get one very far.

Of course, people get very heated over moral concerns; yet the problem is not the heat, but how to settle the dispute. And when it comes to international disputes, that is the question. At no point has NATO seriously tried to settle the dispute—it, like the Ukrainian government, has treated the Minsk Accords with little more than disdain. Yet, like Mr. Kerr, the US government and the mainstream media simply ignore one set of interests and drapes another set of interests in moral costumes as the recognizable good guys.

Also noteworthy is that Mr. Kerr simply ignores the extent of corruption in Ukrainian politics—again, I said enough about this in my earlier essay, but the idea that Ukraine was more authentically liberal democratic than Russia is simply not a serious claim. But this is what happens when people start and end with moral conviction rather than curiosity and acknowledgement of ignorance and a willingness to change their minds.

In Mr. Kerr’s mind one can either go and live in Russia or China, or shut up. Again, I have not heard any critic of NATO’s involvement in this war say that they find Russia or China to be without their own problems. Criticizing the West’s involvement in this war, emphasizing that this is a regional conflict, and that the creation of a proxy war to bring about regime change—is not to be a traitor to the West. It is to express a point of view—which is to say, it is exactly the kind of political engagement that Mr. Kerr says is what the West can deliver, and those who seek change should be involved in. That change, though, can only occur for the better if people can speak freely, even when mistaken, and if they can learn from each other and their mistakes.

That freedom of speech is imperilled in the West has nothing to do with how much censorship exists in Russia or China. Mr. Kerr recognizes the free-speech problems in the West in passing only, yet ignores the extent of its effects in the curricula, appointments and sackings not only in universities, schools, the media, but also in corporations.

As for the press, Mr. Kerr writes “our press is still free, the fact that some choose to self-censure is not proof to the contrary”—apart from its role in a stream of lies about Mr. Trump and his support base (all white supremacists, racists and extremists), led by the biggest whopper that Mr. Trump’s election was due to Russian electoral interference, or that he was a Russian operative or stooge (like all liars the story changed every time a fact was revealed), and the fact that an elected president was banned from using social media platforms which was a historical moment that occurred with nothing but cheers and celebration by the press—the same press that has played a major role in shutting down free speech on pretty well any political position its owners and journalists don’t agree with.

As for Mr. Kerr’s “gee-up speech”—stop whining and roll up your sleeves and get with the program—the problem is that in the West the political process only works if the electorate fits the mould of the ruling elite. While the elite used to be politically divided on all sorts of things, now the room for disagreement is increasingly negligible, because the problems all seem to be of such a catastrophic nature that disagreement risks threatening the survival of the entire planet/species. This was the real lesson of the Trump years—what he was or who he was and what he did were only the issue to the extent that he represented a significant portion of the American population that was to be dismissed as “deplorable,” and to whom no concession was to be made. Irrespective of the facts surrounding the last election being a “steal,” the fact that almost half of the electorate believed it to be so really matters—and to repeat blathering on about the West and its virtues and the freedom fighters of Ukraine is simply displaying a preference for air rather than for understanding reality.

The media has long since lost any credibility for people like me—which is about half of the Western world. So why would we accept their line on this war (and indeed the line of others who just echo and supplement their line, but claim to be more independent)? In my previous essay, I mentioned some of the lies luridly reported about Putin’s army of assassins poisoning anyone who has a bad word to say about him. It is this same media that now states unequivocally that “There was no promise made by James Baker to Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990 limiting eastward expansion of NATO.” Well, I recall the claim about NATO very differently, and long before this war. It was a point regularly bought up by Stephen Cohen, who got along swimmingly well with CNN (after all, he was pretty left on the USSR, an admirer of Bukharin, a guy I think was just another know-all communist butcher) until he started objecting to what they were saying about the Maidan back in 2014, and then the nonsense of 2016.

So, unlike Mr. Kerr, I think that the US involvement in the Maidan, the rebooting of the Cold War by the media, and domestic and international security agencies and military officials in the US during Trump’s presidency, and the present war (notably emboldening the Ukrainian government to ignore the Minsk agreements, as well as intensifying the persecution of Russian first language Ukrainians)—are all of a piece.

I do agree with Mr. Kerr that China is the real great power rival, but everything I see about how the West is conducting itself leads me to believe—it is “good night, Irene.” I don’t want to think that. I think we once had something great, but we threw it away. We rewarded and handed over authority to people who thrived on destroying the West’s values and institutions—that it was the kids at university, with half-baked ideas, and know-all teachers who had read a few books, who started the rot (just as they did in Russia more than a century ago). I don’t blame the Chinese for taking advantage of our idiocy. I don’t love the kind of world they will introduce; as an Australian, I see it more likely to be far more directly obvious here than in the US, which will have its own race wars and breakups to deal with. The US will be too “mah fan,” as the Cantonese say, to bother capturing.

But I don’t hate the Chinese for having their own strategic interests. Apart from that, I have some very close Chinese friends. But were the West better and healthier, we might have something to offer them for joining us. But we don’t; and because we are making the kind of world we are making, we are lurching toward war—whether it be a civil war, or world war is less relevant than the fact that the West is pursuing one policy after another that makes it hell-bent on self-destruction, while it enables its enemies.

Thinking that NATO is saving us from this fate, when it is pushing us toward it, is the issue that really separates those that think like Mr. Kerr and those who think like me. I don’t like what I think—I have said this many times. I think what I see, not what I want.

Of course, I don’t want a third world war, though what I want matters nothing. But Mr. Kerr, whether he realizes it or not, is really clamouring for just that. And Mr. Zelensky has made it very clear that if that be the risk, so be it—and given where he sits between the ethnic nationalists who seem to see him as an irrelevant fool, and Russia—this might not even be his own personal worst option.

As for wanting, no one ever gets what they want, even though they may have the satisfaction of eliminating who or what they see as an obstacle to their ends. The French revolutionaries got rid of the power of the crown, and the Mountain freed themselves of the Girondin “traitors;” but they got the Napoleonic wars rather than liberty, equality and fraternity. The Russian intelligentsia got rid of the Tsar, and they got the gulags and food-queues rather than all the abundance of communism.

Those like Mr. Kerr who think that if they rid the world of Putin they will have some geopolitical advantage in staking out the future—seem to think this might even scare China. But if there is to be a war with China, the US will need to find others to fight that one—their kids will be too caught up in trans rallies, gay pride stuff, and burning down buildings in solidarity with BLM—to put on the uniforms to save their precious way of life.

I don’t know who will win the war, nor how far it will go—the fog surrounding it makes me suspicious of the accuracy of most things I read about it. If the West does get rid of Putin, and does get its regime change, I think it will open the door to one of the oligarchical exiles who, I have long suspected, have been pouring money into Western governments to bring about regime change to take over. From what I read, I don’t think the majority of Russians want that. But in any case, what I know for sure is that the West will still be in the same “merde profonde.”

Wayne Cristaudo is a philosopher, author, and educator, who has published over a dozen books.

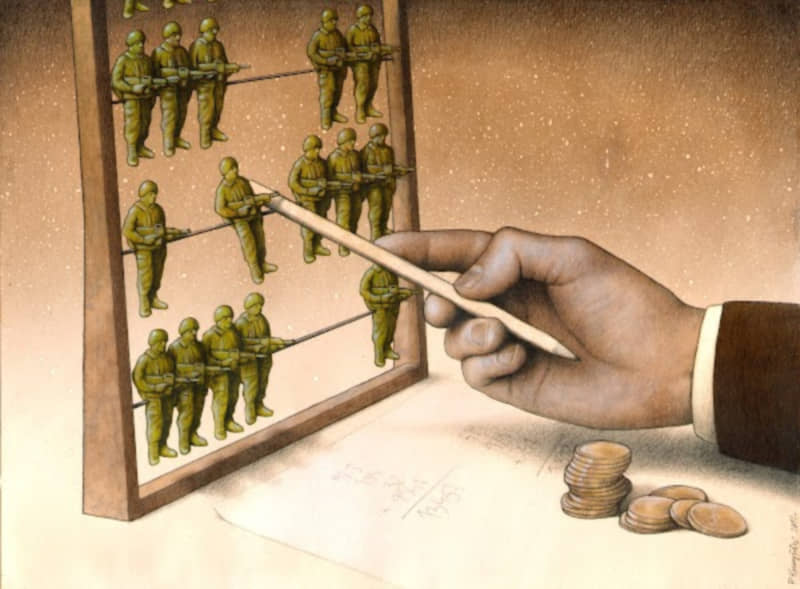

Featured: “Abacus,” by Pawel Kuczynski; painted in 2011.