My approach to God, while drawing inspiration from the Trinitarian Christian god, envisions the latter as, incidentally, symbolizing God and His relationship to the universe. I indeed approach God as an infinite, eternal, substantial, volitional, and conscious field of ideational singular models that completely incarnates itself into the universe while remaining completely external to the universe, completely ideational, and completely subject to a vertical (rather than horizontal) time; and which is not only completely sheltered from any forced effect (whether ideational or material), with one or more efficient causes, in its willingness but traversed, animated, efficiently-caused, and unified by a sorting, actualizing, pulse that both stands as the acting part of God’s will and as the apparatus, the Logos, through which God incarnates Himself while remaining distinct from His incarnation.

In the Trinity, I envision the Father as the symbol of the infinite, eternal, substantial, volitional, and conscious field of ideational singular models as that field both incarnates itself into the universe and remains distinct from the universe; the Son as the symbol of the universe as the latter is both the ideational field’s incarnation and an entity distinct from the ideational field; and the Holy Spirit as the symbol of the sorting, actualizing, pulse through which God incarnates Himself into the universe and yet remains distinct from the universe. The present discourse, which stands as a direct continuation to my “Preliminary considerations on the dignity of man, the Idea of the Good, and the knowledge of essences,” intends to bring whole new preliminary considerations on my part on a number of topics including the substance, emergence, creation, the Chi, war, predestination, mindfulness, freedom, decentralized competition, the pineal gland, and the soul’s (earthly) journey and (divine) origin. On that occasion, I will deliver an assessment of what Benedictus de Spinoza, René Descartes, and Aleister Crowley (and a few other philosophers) respectively wrote on some of those topics.

Beforehand a few remarks concerning my respective definition for some of my concepts should be made. A moment-relative property in an entity (whether ideational—or material) is a property (whether existential—or non-existential) that deals with the point (or points) in time at which the entity itself or one or more properties in the entity are taking place; whether time for the entity is horizontal—or vertical. In an entity (whether ideational—or material), a property preexistent to one or more other properties is a property for which one chronological point, at least, in its existence is chronologically anterior to the existence of the other property or properties in question; whether its existence is already extinguished before the existence of the other property or properties in question. An entity preexistent to one or more other entities (whether it occupies the same realm as the one or more other entities in questions) is an entity for which one chronological point, at least, in its existence is chronologically anterior to (the existence of) the other entity or entities in question; whether its existence is already extinguished before the existence of the one or more other entities in question.

In a realm of reality taken in isolation (whether it is the ideational realm—or the material one), any extrinsically contingent or extrinsically necessary property existing in an entity at some point has strictly three kinds of cause, which are all operating for any extrinsically contingent or extrinsically necessary property in any entity. Namely a relational cause (i.e., one or more relations on the entity’s part at some point before), an existential cause (i.e., the existence of the entity both presently and at the anterior point), and an intrinsically necessary cause (i.e., an intrinsically necessary property in the entity at the anterior point). What’s more, in a realm of reality taken in isolation (whether it is the ideational realm—or the material one), any extrinsically contingent or extrinsically necessary entity existing at some point has strictly three kinds of cause. Namely a relational cause (i.e., one or more relations on another entity’s part: at some point before the concerned caused entity’s existence, except in a few cases), an existential cause (i.e., the existence of the other entity and hypothetically of some other entities which it is having one or more relations with: at the anterior point, except in a few cases), and an intrinsically necessary cause (i.e., an intrinsically necessary property in the other entity and hypothetically in those hypothetical other entities: at the anterior point, except in a few cases).

The relational cause for some (extrinsically necessary or extrinsically contingent) property or entity is that kind of cause that can also be called the “efficient cause.” Saying of an entity that it is an efficient cause (were it the only efficient cause) for one or more extrinsically contingent or extrinsically necessary other entities is a convenient way of saying that one or more relations on that entity’s part are efficient causes (were the relations in question only between the entity and itself) for the one or more entities in question; just like saying of an entity that it is an efficient cause (were it the only efficient cause) for one or more extrinsically contingent or extrinsically necessary properties in that entity or in one or more other entities is a convenient way of saying that one or more relations on that entity’s part are efficient causes (were the relations in question only between the entity and itself) for the properties in question. An efficiently uncaused property is one with no efficient cause; what is only the case of any (strong-kind or weak-kind) intrinsically necessary property.

An efficiently uncaused entity is one with no efficient cause; what is only the case of any (eternal or self-produced) intrinsically necessary entity and the case of that modality of an extrinsically contingent entity that is a randomly self-produced entity. A self-produced entity (whether it is intrinsically necessary) is a temporal-starting-endowed entity that is, besides, self-caused and efficiently uncaused (whether it is intrinsically necessary). When it comes to those extrinsically necessary entities that are the supramundane souls and the ideational essences (whether their realm is taken in isolation), the combination between relational, existential, and intrinsically necessary causes which results into their existence (in the ideational realm) is both internal to the ideational realm and temporally simultaneous to their existence (in the ideational realm). When it comes to those material entities (including the universe) that are considered from the angle of their incarnation-relationship to God, the combination between relational, existential, and intrinsically necessary causes which results into their existence (in the material realm) is both internal to the ideational realm and temporally simultaneous (in the ideational realm) to their existence (in the material realm). Ditto for the properties in those material entities that are considered from the angle of their incarnation-relationship to God.

Any entity (whether it is ideational—or material) is both a caused and causing entity: more precisely, a caused (though not systemically an efficiently caused) and efficiently causing entity. Any act of creation falls within production; but not any act of production falls within creation. Production is to be taken in the sense for a cause (whether it is relational, existential, or intrinsically necessary) of causing the existence of one or more properties that are (not eternal but instead) endowed with a temporal beginning; or the existence of one or more entities that are (not eternal but instead) endowed with a temporal beginning.

As for creation, it is to be taken in the sense of the fact for a cause (whether it is relational, existential, or intrinsically necessary) of producing one or more (temporal-starting-endowed) properties other than moment-relative that are (completely or partly) novel with respect to what characterizes the (existential or non-existential) properties other than moment-relative that have been witnessed in the entities having been witnessed in the concerned realm of reality (i.e., the existential or non-existential properties other than moment-relative that are characteristic of the entities that either are or used to be or have been being in the concerned realm of reality); or the existence of one or more (temporal-starting-endowed) entities that are (completely or partly) novel in their properties (other than moment-relative) with respect to what characterizes the existential or non-existential properties other than moment-relative that have been witnessed in the entities having been witnessed in the concerned realm of reality.

Not only any efficiently caused entity (i.e., any entity with one or more efficient causes) that is temporal-starting-endowed is a produced entity (i.e., a caused entity that is endowed with a temporal beginning); but, reciprocally, any produced entity is an efficiently caused entity that is temporal-starting-endowed. Not only any efficiently uncaused entity (i.e., any entity devoid of the slightest efficient cause) is a self-caused entity (i.e., a caused entity that is randomly self-produced or intrinsically necessary); but, reciprocally, any self-caused entity is an efficiently uncaused entity.

A self-produced entity (i.e., a self-caused entity whose existence is, besides, endowed with a temporal beginning) and a substance (i.e., a self-caused entity whose existence is, besides, intrinsically necessary and, at every point, endowed with a strong intrinsically necessary eternity remaining throughout the entity’s existence by strong intrinsic necessity) are two distinct modalities of a self-caused entity; but both a self-produced entity and a substance are efficiently uncaused.

Any entity that is (completely or partly) novel in its properties (other than moment-relative) with respect to what characterizes the existential or non-existential properties other than moment-relative that have been witnessed in the entities having been witnessed in the concerned realm of reality falls within emergent entities in the concerned realm of reality; just like any property other than moment-relative that is (completely or partly) novel with respect to what characterizes the (existential or non-existential) properties other than moment-relative that have been witnessed in the entities having been witnessed in the concerned realm of reality falls within emergent properties in the concerned realm of reality.

Any emergent entity is either ideational or material; just like any emergent property is either a property in an ideational entity or one in a material entity. In a few lines, I will deal more closely with the concept of emergence; and with the respective concepts of existential and non-existential properties. It is worth clarifying that, while the way one understands some concept lies in the way one identifies (what one believes to be) all or part of the properties in the concept’s object, the way one defines some concept lies in the way one identifies (what one believes to be) the whole of the constitutive properties in the concept’s object. One’s “understanding of some concept” and one’s “approach to some concept” are phrases that can be used interchangeably.

Emergence and Creation: The Substance and the Chi

A material entity is an entity endowed with some kind of firmness, consistency (for instance: a quark, the void, an idea in a parrot’s mind, a movie, or the Chi); just like an ideational entity (i.e., an Idea) is an entity devoid of any firmness, consistency. A property is what is characteristic of an entity (whether the entity in question is ideational—or material) at some point (whether time for the entity in question is horizontal—or vertical). Any property is either existential or non-existential. A non-existential property in an entity (i.e., a property in the entity that is not relative to the entity’s mode of existence) is either compositional or formal or a composite of form and of composition; what is tantamount to saying: a composite of formal and compositional properties. An existential property is a property that is, if not relative to the entity’s existence’s origin or relative to whether and how the entity’s existence is (at some point) permanent or provisory, at least relative to the entity’s mode of existence, i.e., the entity’s way of existing. A strong existential property is a property that, among the properties relative to the entity’s mode of existence, deals with the entity’s existence’s origin or deals with whether and how the entity’s existence is (at some point) permanent or provisory.

Just like any strong existential property in a material entity is part of the entity’s substantial natural material essence, any strong existential property in an entity (whether it is ideational) is remaining throughout the entity’s existence by intrinsic necessity of the strong kind, i.e., remaining throughout the entity’s existence with the entity’s existence at some point being a necessary, sufficient, condition for its remaining throughout the entity’s existence. An eternal entity is one with no (temporal) beginning and with no (temporal) ending; what falls within the entity’s strong existential properties. Not any eternal entity is an intrinsically necessary entity; but any eternal entity is eternal (at some point) in a strong intrinsically necessary mode and remains eternal (throughout its existence) by strong intrinsic necessity.

A substance is an intrinsically necessary eternal entity whose eternity at some point not only occurs in a strong intrinsically necessary mode but remains throughout its existence by intrinsic necessity of the strong kind. Not any intrinsically necessary entity is a substance; but any entity eternal by strong intrinsic necessity (at some point) is remaining eternal (throughout its existence) by strong intrinsic necessity (and reciprocally). An innate property in an entity (whether it is ideational—or material) is one that is, if not remaining in the entity throughout the entity’s existence, at least accompanied with the strong existential property of a temporal beginning for the entity and present in the entity at the moment of the entity’s temporal beginning; just like an eternal property in an entity (whether it is ideational—or material) is one that, besides remaining in the entity throughout the entity’s existence by strong intrinsic necessity, takes place within an entity both eternal in a strong intrinsically necessary mode and eternal in a strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode.

A property that is arising at some point in an entity is a property in the entity that is neither innate nor eternal in the concerned entity; just like an entity that is arising at some point is an entity (in some realm of reality) that is neither innate nor eternal in the concerned realm. Any property eternal in an entity is present at some point by strong intrinsic necessity and remaining (and eternal) in the entity throughout the entity’s existence by strong intrinsic necessity; just like any entity eternal in a realm of reality is eternal at some point by strong intrinsic necessity and remaining eternal by strong intrinsic necessity.

In an entity (whether it is ideational—or material), whether its realm is taken in isolation, a property other than moment-relative that is irreducible to all or part of the preexistent properties other than moment-relative in the entity is one that is neither completely characterized identically to any of the preexistent properties other than moment-relative in the entity nor completely characterized identically to a combination between all or part of the preexistent properties other than moment-relative in the entity (whether all or part of the preexistent properties other than moment-relative are still existent—or now inexistent); just like, in a realm of reality (whether it is ideational—or material), whether that realm is taken in isolation, an entity that is irreducible in its properties other than moment-relative to all or part of the properties other than moment-relative in those preexistent entities causing efficiently its existence is one for which one of its properties other than moment-relative, at least, is neither completely characterized identically to all or part of the properties other than moment-relative found in the set of those preexistent entities causing efficiently its existence nor completely characterized identically to a combination between all or part of the properties other than moment-relative found in the set of those preexistent entities causing efficiently its existence (whether all or part of those entities are still existent—or now inexistent).

An emergent property in an entity (whether it is ideational—or material) is a property other than moment-relative that is, if not irreducible to all or part of the preexistent properties other than moment-relative in the entity, at least arising at some point in the entity (instead of being innate or eternal in the entity); just like an emergent material entity is a material entity that is, if not arising at some point in the universe (instead of being the universe itself or one of the very first entities chronologically in the universe), at least irreducible in its properties (witnessed over the course of its existence) other than moment-relative to all or part of the properties other than moment-relative in those preexistent entities causing efficiently its existence.

A strong emergent property and a strong emergent material entity are respectively a property other than moment-relative that, besides arising at some point in the concerned entity (instead of being innate or eternal in the entity), is irreducible to all or part of the preexistent properties other than moment-relative in the entity; and a material entity that, besides being irreducible in its properties other than moment-relative to all or part of the properties other than moment-relative in those preexistent entities causing efficiently its existence, is arising at some point in the universe (instead of being the universe itself or innate in the universe).

Any emergent property is either a quality (i.e., a non-existential property) other than moment-relative or an existential property other than moment-relative; but not any quality other than moment-relative nor any existential property other than moment-relative fall within emergent properties. An emergent entity (whether it is ideational—or material) is an entity that is, if not arising at some point in its realm of reality, at least irreducible in its properties (witnessed over the course of its existence) other than moment-relative to all or part of the properties other than moment-relative in those preexistent entities causing efficiently its existence; just like an emergent ideational entity is an ideational entity that is not only eternal but irreducible in its properties (witnessed over the course of its existence) other than moment-relative to all or part of the properties other than moment-relative in those preexistent entities causing efficiently its existence.

A strong emergent property and an emergent entity are both introducing—when (and only when) the strong emergent property in question and one property, at least, in the emergent entity in question are characterized in a way that is then unprecedented (whether completely or partly) in the concerned realm of reality—a certain novelty (whether complete—or partial) in the field of what characterizes the properties other than moment-relative that have been witnessed in the entities having been witnessed in the concerned realm (i.e., the properties other than moment-relative that are characteristic of entities that either are or used to be or have been being in the concerned realm).

Any novelty (whether complete—or partial) introduced (at some point) in the field of what characterizes the existential or non-existential properties other than moment-relative that have been witnessed in the ideational or material realm’s entities having been witnessed (i.e., the properties other than moment-relative that are characteristic of entities that either are or used to be or have been being in the ideational or material realm) is introduced by (and through) an (other than moment-relative) property that is either a strong emergent property or a property in an emergent entity or a property that is both; but not any strong emergent property introduces some novelty in that field, no more than does any emergent entity.

The universe is both an extrinsically contingent emergent material entity from the angle of its relationship to the nothingness chronologically prior to the universe; and, from the angle of its relationship to God, an extrinsically necessary emergent material entity (distinct from God and yet identical to Him) whose incarnation-relationship to God is an eternal (rather than emergent) property in God Himself. Whether it is from the angle of its relationship to the chronologically anterior nothingness or from the angle of its relationship to God, the universe isn’t an intrinsically necessary entity endowed (at every point) with an eternity both intrinsically necessary in a strong mode and intrinsically necessarily remaining in a strong mode (i.e., a substance); no more than it is, generally speaking, an intrinsically necessary entity.

In the field of philosophy, translating into one’s language another philosopher’s concepts consists of expressing the latter’s concepts—and the way they’re understood and defined in the latter—through one’s concepts (such as one understands and defines them) in a way that nonetheless stays completely faithful to what are that someone else’s concepts and his understanding and definition of his concepts. To put it completely in my language, Spinoza’s approach to God in Ethics correctly portrays Him as an intrinsically necessary entity eternal in a strong intrinsically necessary mode whose eternity is remaining (throughout His existence) by intrinsic necessity of the strong kind, and which is composed (at every point) of an infinite number of non-existential constitutive properties; and as the only entity that is composed (at every point) of an infinite number of non-existential constitutive properties—and as the only entity that is a substance, i.e., the only entity that is endowed (at every point) with an intrinsically necessary existence and with an eternity both intrinsically necessary in a strong mode and remaining in a strong intrinsically necessary mode throughout the entity’s existence.

That approach nonetheless commits a mistake that lies in its confusing the being an eternal entity and the being an entity with no temporal ending; and in its confusing the being an intrinsically necessary entity with no temporal ending and the being an entity devoid of any temporal ending. Any eternal entity (as is the case of a substance) and any entity devoid of any temporal ending (as is the case of a substance) are respectively eternal—and devoid of any temporal ending—in a strong intrinsically necessary and strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode; but, just like an eternal entity is only a modality (i.e., only a certain kind) of an entity with no temporal ending, an intrinsically necessary entity with no temporal ending is only a modality of an entity devoid of any temporal ending.

Though the universe cannot end in time (whether it is with regard to the nothingness—or with regard to God), it is an extrinsically contingent (rather than intrinsically necessary) entity with regard to the nothingness chronologically anterior to the universe; and, with regard to God, an extrinsically (rather than intrinsically) necessary entity. Accordingly the fact of being devoid of any temporal ending is not (as Spinoza wrongly asserts) unique to the eternal entity that is a substance; though there is indeed only one substance as Spinoza rightly asserts. Another mistake Spinoza’s approach to God commits lies in its confusing the being an efficiently uncaused entity and the being an intrinsically necessary eternal entity whose eternity takes place in a strong intrinsically necessary and strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode (i.e., a substance); and in its confusing the being an intrinsically necessary entity and the being a substance.

An extrinsically contingent and efficiently uncaused entity (i.e., a self-produced entity) and an intrinsically necessary and efficiently uncaused entity (whether it is a substance) are two distinct modalities of an efficiently uncaused entity; just like an intrinsically necessarily eternal (in a strong mode), intrinsically necessarily remaining eternal (in a strong mode), and intrinsically necessary entity—and an intrinsically necessary entity that is, if not devoid of any temporal ending, at least endowed with a temporal beginning—are two distinct modalities of an efficiently uncaused entity. The universe and God are respectively an efficiently uncaused entity of an extrinsically contingent kind (with regard to the nothingness chronologically prior to the universe) and an efficiently uncaused entity of an intrinsically necessary kind; just like God and the universe’s very first components chronologically (such as the quarks and the Chi) are respectively an efficiently uncaused and intrinsically necessary entity of an intrinsically necessarily remaining eternal (in a strong mode) kind and (with regard to the nothingness chronologically prior to the universe) efficiently uncaused entities that are intrinsically necessary but devoid of any eternity at any point.

Accordingly, the fact of being intrinsically necessary is not (as Spinoza wrongly asserts) unique to the substance; though there is indeed only one substance. Yet another mistake in Spinoza’s approach to God lies in its misunderstanding God’s complete coincidence with the universe to exclude the slightest degree and form of independence of God with regard to the universe. God is both completely identical and completely external to the universe—in that He gets completely incarnated into the universe while remaining completely distinct from the latter. Yet another mistake in Spinoza’s approach to God lies in his misunderstanding time for God to be horizontal (rather than vertical); and in its misunderstanding God’s non-existential constitutive properties to exclude any ideational property.

Though God (as Spinoza rightly asserts) is indeed the only substance, God finds itself placed under a vertical (rather than horizontal) time; and its non-existential constitutive properties find themselves to be exclusively composed of ideational properties (including ideational essences). Neither the “extension” realm nor the “thought” realm nor the indeterminate other realms which Spinoza thinks to be non-existential constitutive properties in God qualify as ideational realms (in my language).

Another mistake in Spinoza’s approach to God lies in its misunderstanding God’s non-existential constitutive properties to be both infinite and of an infinite number; and God’s non-existential properties not to be all constitutive. Though the substance is indeed composed of an infinite number of non-existential constitutive properties (since the ideational essences are of an infinite number), Spinoza as much misses the fact that all the substance’s non-existential properties are constitutive as he misses the fact that not all of them are infinite.

Yet another mistake in Spinoza’s approach to God lies in its misunderstanding God not to be endowed with some willingness and not to expect something from the human. Though God is indeed identical to the unique substance (as Spinoza rightly asserts), the substance is (at every point) a volitional entity (i.e., an entity endowed with willingness) and even a conscious volitional entity (i.e., an entity endowed with conscious willingness); and a conscious volitional entity that expects something from the human. Namely that the human, through rendering himself sufficiently like-divine in the material realm, render his soul completely divine in the ideational realm. I will not discuss here whether the notion of entities or properties that are arising at some point (instead of being innate or eternal) or irreducible is lacking (were it partly) in Spinoza’s philosophy; but the cosmos in Spinoza, besides being identified to God in a way that wrongly excludes any externality of God with regard to the cosmos, is just as wrongly envisioned as a perfect and achieved entity that excludes the slightest novelty (with respect to the existential or non-existential properties other than moment-relative that have been witnessed in the entities having been witnessed within the cosmos).

The fact for the human of being “in the image of God” is to be taken in the sense for the human of being endowed (in his substantial natural material essence) with a grandly (but not completely) self-determined willingness with regard to matter; of being in a position, not to remedy the cosmic order (were it partly), but instead to bring reparation and completion to the universe in strict conformity with the universe’s underlying order and laws; and of being in a position to know reality and the universe in a way that is irremediably perfectible.

The Spinozian approach to God is a complete offense to Him in that it demeans Him to the level of nature instead of envisioning nature as His incarnation or product or even as an emergent property in Him; just like the Spinozian approach to the human grandly (though not-completely) offenses what, in the human being, is “in the image of God.” It denies just as much the slightest degree of self-determination in the human will with regard to the efficient causes at work in nature as the slightest possibility of novelty (with respect to the existential or non-existential properties other than moment-relative that have been witnessed in the entities that have been witnessed) and therefore of creation in the realm of nature as the slightest role to be played for the human’s creation with regard to an allegedly perfect nature where nothing would be to be repaired nor to be perfected.

The Spinozian offense to what, in the human being, is “in the image of God” remains incomplete in that Spinoza, instead of envisioning the human as able to reach perfect knowledge of the nature, holds him for irremediable unable to have the slightest knowledge of any other “attribute” in the “substance” than the “thought” and than the “extension.”

As concerns creation on a human’s part, it is worth noting that, while an idea created in a human’s mind (or, for instance, in a dachshund’s mind) is a produced idea introducing some novelty (either complete or partial) in the field of what characterizes the properties (other than moment-relative) having been witnessed in those ideas having been witnessed in the universe, a creative idea created in a human’s mind (or, for instance, in a dachshund’s mind) is an inspirationally produced idea introducing some novelty (either complete or partial) in the field of what characterizes the properties (other than moment-relative) having been witnessed in those ideas having been witnessed in the universe. In other words, a creative idea (created in a human’s mind or, for instance, in a dachshund’s mind) is a modality of a created idea—namely that it is a created idea the efficient cause of which lies in an inspiration-relationship of the mind in question with respect to all or part of those entities having been witnessed in the concerned realm of reality. Not only not any creation on a human’s part consists of a created idea; but not any created idea on a human’s part consists either of a creative idea.

An exploit is to be taken in the sense of an act that is jointly exceptionally creative (i.e., characterized with the mind’s creation of one or more exceptionally creative ideas), exceptionally successful (i.e., characterized with the complete fulfillment of an exceptionally hard goal), and exceptionally endangering for one’s subsistence. The Spinozian ethics, in that it exclusively situates the human’s happiness in the “persevering in one’s being” here below, is a (complete) offense to what in the human’s happiness cannot be reached in an earthly lifetime exclusively or primarily dedicated to the persevering in one’s material existence. That part in the human’s happiness, the highest, noblest, part, which lies in the accomplishment of exploits (i.e., the accomplishment of acts that are jointly exceptionally creative, exceptionally successful, and exceptionally endangering for one’s subsistence), is basically dismissed in what can be called Spinoza’s “conatus ethics,” which is basically an ethics of mediocrity.

Just like the entities are subdivided between those inhabiting the ideational realm and those inhabiting the material realm (which stands as the materially incarnated ideational realm), the Being (i.e., what allows for the entities to exist without being itself an entity) contains both a realm correspondent to the ideational entities; and a realm correspondent to the material entities, which stands as the material incarnation of the latter realm. “The materially incarnated Being” and “the ideational Being” are convenient ways of designating respectively that realm of the Being correspondent to the material entities; and that realm of the Being correspondent to the ideational entities.

Any intrinsically necessary entity is an emergent entity; but not any extrinsically necessary entity is an emergent entity, no more than any emergent entity is an intrinsically necessary entity. Though the universe is God’s incarnation, the universe’s ideational essence does not lie in God Himself—but instead in the Idea of the universe, which is not only infinite and incomplete but in constant updating. Just like any material entity other than the universe stands as the incarnation of some ideational essence, any material entity other than the Chi and other than the universe stands as the incarnation of some finite and achieved ideational essence.

The Chi stands as the incarnation of what I previously called (following Plato) the “Idea of the Good,” which would be more judiciously called the “Idea of the Chi” and that is genuinely the sorting, actualizing, pulse at work in the ideational field; but the Idea of the Chi, though it gets incarnated (like any Idea other than the Idea of the universe), is jointly infinite (like the Idea of the universe—but unlike any Idea other than the Chi’s Idea and than the universe’s Idea), incomplete (like the Idea of the universe—but unlike any Idea other than the Chi’s Idea and than the universe’s Idea), and in constant updating (like the Idea of the universe—but unlike any Idea other than the Chi’s Idea and than the universe’s Idea).

I approach that entity known in Chinese and Japanese ontologies to be the “Chi” as a material entity (internal to the universe) that can be described as mere energy enveloping, at every point, every other entity in the universe; and which, without causing itself the slightest property or entity, makes it possible to cause the emergent properties (including the strong emergent properties) present (at some point) within some entity (whether innate—or arising) present (at some point) in the universe and makes it possible to cause some entity (whether innate—or arising) present (at some point) in the universe (including those entities in the universe that are emergent).

Just like the Chi stands as the incarnation of the sorting, actualizing, pulse through which, at every point in the ideational realm (for which time is strictly vertical), some ideational models see their correspondent hypothetical material entities being introduced, concretized, in the material realm and others their correspondent hypothetical material entities being denied, not-concretized, in the material realm, the sorting, actualizing, pulse itself stands as the Idea of the Chi, i.e., the Chi’s ideational essence. A mistake in the Spinozian approach to the substance is to confuse the being a substantial entity and the being an entity eternal in a strong intrinsically necessary and strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode. Though there is indeed only one substance (as Spinoza rightly asserts), an intrinsically necessary entity eternal in a strong intrinsically necessary and strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode (i.e., a substance) is only a modality of an entity eternal in a strong intrinsically necessary and strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode.

Just like the Idea of the Chi is an eternal (in a strong intrinsically necessary and strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode) but extrinsically necessary emergent entity whose efficient cause lies in the substance that is God, the ideational essences other than the Idea of the Chi are eternal (in a strong intrinsically necessary and strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode) but extrinsically necessary emergent entities the efficient cause of which lies in the Idea of the Chi. Just like the Chi stands as the transition between the materially incarnated Being and the other material entities (including the universe), God stands as the transition between the ideational Being and the ideational essences (including the Idea of the Chi).

The universe is a God-production (i.e., a temporal-starting-endowed entity whose efficient cause lies in God) and even a God-creation (i.e., a temporal-starting-endowed entity whose efficient cause lies in God and whose introduction in the material realm has been bringing novelty there in terms of what characterizes the properties other than moment-relative); but it is so not in that the universe would be in God an emergent property (and even strong emergent property introducing such novelty in the material realm) that finds its efficient cause in God—but instead in that the universe stands as a God-incarnation. More precisely, the universe is God-created neither as a product (i.e., a production to which its efficient cause or causes remain strictly external) nor as an emergent property; but instead as a production in which God gets completely incarnated while remaining completely external to His incarnation. In any entity, the whole is only the unified sum of the parts: except in the case of the universe and in the case of the substance.

As much the substance taken as a whole as its parts (and therefore the ideational essences it contains) are eternal in a strong intrinsically necessary mode and strong intrinsically necessarily remaining mode; but the substance taken as a whole exists independently of its parts though simultaneously to its parts, to which it communicates its eternity intrinsically necessary of the strong kind and remaining throughout existence by strong intrinsic necessity.

When considered independently of their incarnation-relationship to God, as much the universe taken as a whole as its very first parts (i.e., those of its parts that, including the Chi, appeared with the “big bang”) are self-created; but the universe taken as a whole exists as much simultaneously to its parts as independently of its parts: including its very first parts, which are intrinsically necessary while the universe itself is extrinsically contingent. The substance, as it is intrinsically necessary, is self-caused and efficiently uncaused; but the substance, as it is not only intrinsically necessary but remaining eternal throughout its existence by intrinsic necessity of the strong kind, is not only self-caused and efficiently uncaused but devoid of any self-produced character. The incarnation-relationship from God into the universe is, in God, neither an efficiently uncaused strong-emergent relational property nor, generally speaking, an emergent relational property; though it is indeed efficiently uncaused.

While the universe (when considered from the angle of its incarnation-relationship to God) is an emergent extrinsically necessary entity finding in God its efficient cause, which is not only irreducible (in its properties other than moment-relative) to (all or part of the properties other than moment-relative in) God but introducing novelty (in terms of what characterizes the properties other than moment-relative) in the material realm, the incarnation-relationship from God into the universe is, for its part, an eternal and strong-kind intrinsically necessary relational property.

When considered from the angle of its relationship to the nothingness chronologically prior to the universe, the latter is an extrinsically contingent emergent entity whose existence is even devoid of any efficient cause; but, when considered from the angle of its relationship to God, the universe is an extrinsically necessary emergent entity whose existence is the forced rather than random effect of the combination (concomitantly to the universe’s material existence in the strictly vertical time applying to the ideational realm) between God’s existence, God’s incarnation-relationship to the universe, and the character of that incarnation-relationship as an eternal and strong-kind intrinsically necessary property in God.

When considered from the angle of its relationship to the nothingness chronologically prior to the universe, the Chi is an intrinsically necessary emergent entity whose existence is therefore devoid of any efficient cause; but, when considered from the angle of its relationship to God, the Chi is an extrinsically necessary emergent entity whose existence is the forced rather than random effect of the combination (concomitantly to the Chi’s material existence in the strictly vertical time applying to the ideational realm) between God’s existence, God’s incarnation-relationship to the universe, and the character of that incarnation-relationship as an eternal and strong-kind intrinsically necessary property in God.

The Role of Genetic Similitude in a Society’s Cohesion—and in Providence’s Outworking

The way the sorting, actualizing, pulse operates in the ideational realm expresses a part of God’s will, but only a part precisely. Namely that part of God’s will that is acting (i.e., using means for the purpose of goals); and which must be distinguished from that part of His will that involves goals without involving any means. The Providence is to be taken in the sense of the acting part of God’s will as His will’s acting part is at work in cosmic and human history. War is to be taken in the sense of a physical, coercive, struggle between groups (whether the latter are groups of living beings).

When he presented war as “the world’s only hygiene,” Marinetti would have done better to present it as “one of the world’s hygienes,” alongside famine and epidemics notably. Above all, he should have specified that the hygiene of war is “God’s hygiene for His incarnation as the latter is a world tirelessly in search of progress in order and complexity.” For war is one of the hygienic apparatuses (and even one of the privileged ones) through which the Providence strives to maximize as much as possible the probability in the universe (throughout the universe’s existence) that the least sophisticated groups in terms of order and complexity (both internal and at the level of intergroup relations) at some point, instead of encumbering God for the rest of the universe’s days, end up disappearing in the short run or, failing that, in the long run.

Also, war is one of the incentive apparatuses (and even one of the privileged ones) through which God strives to maximize as much as possible the probability in the universe (throughout the universe’s existence) that geniuses in the cognitive field be promoted (rather than devalued) in society; and, accordingly, their sexual reproduction (and therefore their genetic frequency) favored rather than hindered in society. Another incentive apparatus through which the Providence strives to maximize as much as possible the probability in the universe (throughout the universe’s existence) that geniuses in the cognitive field be promoted (rather than devalued) in society consists of a culture that values (instead of disdaining), if not the search for exploit in the military field, at least the transposition of the search for military exploit to the cognitive field; in other words, a culture that values (instead of disdaining), if not the search for exploit on the military battlefield, at least the search for exploit on the respective cognitive battlefield of painters, mathematicians, engineers, writers, philosophers, physicists, or movie directors (among other examples). I will come back to those two incentive apparatuses later.

In addition to its character as hygiene for the world, a nevertheless fallible hygiene, war is one of the laws which God (infallibly) wanted for this world and which He (infallibly) wanted to frame the human’s reparation and completion of the divine creation. With regard to those wars implemented among societies of living beings, they as much involve societies characterized by a degree of kin-relatedness such that their members form an “extended family” or even a single family (or what is strongly or moderately a single family) as societies whose members form neither an “extended family” nor (were it only to some strong or moderate extent) a family stricto sensu.

Just like a group whose all members, at some point, are kin-related (to each other) is to be taken in the sense of a group whose members, at some point, are all biological brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, uncles, aunts, sons, daughters, or first cousins with each other, a group whose all members, at some point, are kin-related (to each other) to some extent (rather than to a complete extent) is to be taken in the sense of a group whose members, to some extent (rather than to a complete extent), are all biological brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, uncles, aunts, sons, daughters, or first cousins with each other at some point.

Just like the degree of kin-relatedness at some point in some group is to be taken in the sense of the degree to which people in the group in question are all kin-related (to each other) at some point, the degree of genetic similitude at some point in some group is to be taken in the sense of the degree to which the respective sets of genes present in each of the members of the group in question have similitude with each other at some point.

Setting aside the case of a hypothetical future group whose reproduction would occur through cloning (whether solely or partly), the level of genetic similitude in some group is necessarily a reflection (and measurement) at the genetic level of the level of kin-relatedness in the group in question. The levels of kin-relatedness and of genetic similitude are both part of the substantial natural material essence in any group of living beings. The notion that selection over the course of biological evolution (i.e., over the course of the evolution of the respective genomes in each of the individual members of the different species) only occurs at the level of the individual’s genes and at the level of those genes shared in individuals who are completely kin-related or, failing that, kin-related to a strong or moderate extent can be understood in two distinct ways strictly.

On the one hand, a modality of the notion in question claiming that the struggle for life and reproduction (whether it occurs in a coercive, physical, way) only involves individuals facing other individuals and groups whose members are, at every point, all kin-related (were it only to a strong or moderate extent—rather than to a complete extent) facing other groups of that kind. On the other hand, a modality claiming that survival in the short run (i.e., over the scale of a few decades) is impossible to any group whose members are neither completely nor strongly nor moderately all kin-related to each other. Both modalities are wrong. While the former is disproved by the fact that, in some species (including the human), the intergroup struggle for survival occurs between groups who are not systemically composed strictly of individuals who are, at least to some strong or moderate extent, all kin-related to each other, the latter is disproved by the fact that, in some species (including the human), the intergroup struggle for survival doesn’t witness—whether it is in the long run or in the short run—a systematically compromised situation nor a systematic disintegration of those groups whose members are not, were it only to some strong or moderate extent, all kin-related to each other.

A commonly invoked argument in favor of the claim that, in humans, those groups whose members are not all, were it only to some strong or moderate extent, kin-related are unlikely (though not unable stricto sensu) to survive in the short run is that a gene or team of genes can favor instead of compromising its propagation in the decades yet to come (and, generally speaking, in the centuries or millennia yet to come) only through predisposing the individual to one or more behavioral patterns favoring instead of compromising said propagation.

Yet the fact that such groups sometimes manage to survive in the short run (or even in the long run, i.e., in the centuries or millennia yet to come) doesn’t only disprove the claim that those groups whose members are not all, were it only to some strong or moderate extent, kin-related to each other are unable to survive in the short run. It also corroborates the claim that, in humans, a gene or team of genes can favor instead of compromising its propagation in the long run (and therefore in the short run) not systemically through predisposing the individual to one or more behavioral patterns that favor instead of compromising the propagation of its genes or, failing that, those of its genes shared with a group whose members, whether completely or to an extent that is strong or moderate, are all kin-related to each other; but instead through predisposing the individual to one or more behavioral patterns that favor instead of compromising the propagation of those genes it shares with (and in) a group whose members, while being not all kin-related to each other to an extent that is either complete or strong or moderate, still possess some level of genetic similitude that allows speaking of the concerned group as an “enlarged kinship,” “extended family.”

Society is to be taken in the sense of that kind of group (not necessarily human), sometimes called a “superorganism,” that unites (and encompasses) children, parents, and grandparents; and which hypothetically falls within some larger group like, say, an empire. In view of a number of male partners for a queen oscillating between three and eight in the vespula maculifrons, or between four and ten for a queen in the acromyrmex octospinosus (hence a genetic similitude between sisters around 33%), or even between seven and twenty for a queen in the apis mellifera (hence a genetic similitude between workers around 30%), societies in the hymenoptera are not all a case of a society whose all members are completely (or, at least, strongly or moderately) kin-related to each other.

A thus corroborated claim is that the duplicative success (in the very next decades) of those genes shared among the members of a hymenoptera society, instead of being systemically the result of kin selection (i.e., the result of that kind of group selection dealing with the genes common to some group in which the degree of kin-relatedness is either complete or strong or moderate), is not systemically proportionate to the degree to which people in a hymenoptera society are all kin-related to each other. Yet it seems that, in some species like the wasp, the ant, the bee, and the human, the duplicative success of those genes shared among the members of a society can be the result of a kind of group-selection dealing with those genes common to groups whose members, without being all kin-related to each other to a degree that is either complete or strong or moderate, nevertheless possess a certain degree of genetic similitude which remains strong enough to allow speaking of said members as forming an “extended family,” “enlarged kinship.”

Group cohesion for an individual in some group is to be taken in the sense of the joint fact of identifying oneself as a member of that group one happens to belong to, of acting on behalf of one’s perceived group-interests (i.e., the interests of one’s group such as one perceives them), of privileging in one’s relationships (including economic and professional) the other individual members within one’s group, of behaving in a way that favors (instead of compromising) the survival of one’s group (were it through compromising one’s own survival or one’s reproduction), and of being faithful, docile, with respect to the axiological and organizational principles foundational in one’s group.

The average level of group-cohesion in a group’s individual members is part of the group’s substantial natural material essence. It is regrettable that, all too often, the (other) investigations of the genetic and instinctual underpinnings of a society’s group-cohesion (i.e., group-cohesion among the members of a given society) in homo sapiens remain anchored in the confusion between group-selection and kin-selection; and in the mistaken approach to the intensity of group-cohesion in a given human society as (positively) proportionate to the degree of genetic similitude in the concerned society.

The differences between human societies in the degree of intra-society genetic similitude are no more systemically at the origin of the differences between human societies in the intensity of intra-society group-cohesion than the inter-species differences in the intra-species average degree of genetic similitude in the intra-species societies are systemically at the origin of the inter-species differences in the intra-species average degree of group-cohesion in the intra-species societies.

It is true that a complete degree of genetic similitude in some society (whether it is one human) and a high degree of genetic similitude in some society (whether it is one human) cannot but result respectively into a correspondingly complete degree of group-cohesion—and a correspondingly high or complete degree of group-cohesion—in the concerned society; but it is just as true that a low degree of genetic similitude in a human society doesn’t result into a correspondingly low degree of group-cohesion in said society systemically.

In the human, those societies who manage to survive (whether it is in the short run only or in the long run), what necessarily requires a degree of group-cohesion that is either strong or complete, are societies who are, if not composed of people all kin-related to each other to an extent that is complete, strong, or moderate, at least composed of people in which group-cohesion is strong or complete. In the human, just like those societies in which group-cohesion in people is complete (and those societies in which group-cohesion in people is high) are not systemically societies in which all people are kin-related to an extent that is either complete or strong or moderate, those societies in which the displayed degree of genetic similitude is such that their members form what can be called extended kinships are systemically societies in which the extent to which people are all kin-related to each other is neither complete nor strong nor moderate.

What’s more, in the human, those societies in which group cohesion is complete include (strictly) as much societies with an either complete or strong or moderate level of kin-relatedness as societies who—instead of approaching or forming a (single) kinship stricto sensu—are forming an extended kinship as societies who are neither approaching a single kinship nor forming a single kinship nor forming an extended kinship. Likewise those societies in the human in which group-cohesion in people is high include (strictly) as much societies with an either complete or strong or moderate level of kin-relatedness as societies who—instead of approaching or forming a (single) kinship stricto sensu—are forming an extended kinship as societies who are neither approaching a single kinship nor forming a single kinship nor forming an extended kinship.

Whatever the degree of group-cohesion and whatever the degree of genetic similitude, it nonetheless turns out that, in the human (and perhaps in some other species), culture is never totally independent from genetics. Culture is to be taken in the sense of the set of those behavioral patterns in a society that are inculcated in the society in question (whether it is one human). Some of the cultural patterns (but not all) in a society are part of the society’s substantial natural material essence.

When it comes to a culture totally or partly endowed with an endogenous origin, culture is not only able to contradict, in part, the average genetic features—but wholly able to include patterns that have no connection to genetics (setting aside the issue of knowing whether such patterns can be in contradiction with genetics). More precisely, it is then, on the one hand, wholly able to include behavioral patterns that are not genetically rooted at all (setting aside the issue of knowing whether such patterns can be in contradiction with genetics); on the other hand, unable to contradict the slightest average biological-ability in the group but able to contradict a part (but only a part) of those average genetic features that are about emotions and emotional needs (rather than about abilities).

When it comes to a culture totally endowed with a foreign origin, culture is wholly able to include patterns with no connection to genetics (setting aside the issue of knowing whether such patterns can be in contradiction with genetics); but, also, it is wholly able to contradict the average genetic features—except that it cannot go against the average levels of biological-abilities.

In turn, culture (whether its origin is completely exogenous—or instead completely or partly endogenous) has an effect on genetics in that it hampers the social integration (and therefore sexual reproduction) of those individuals unsuited to the established cultural patterns; in that it influences the tenor of the fertility gap in those individuals managing to reproduce; and in that it influences the propagative success of a certain genetic mutation through influencing the ability of those individuals endowed with the genetic mutation in question to reproduce (and their reproduction’s magnitude). It is regrettable that the (other) investigations of the gene-culture coevolution (i.e., the mutual influence between gene and culture over the course of their respective evolutions) all too often overlook the complexity of said coevolution, treating (more or less surreptitiously) a group’s culture at some point as strictly equal to the group’s average genetic features at that point in time.

In humans, just like one way a gene or team of genes can favor instead of compromising its duplication (in the long run besides in the short run, i.e., over the scale of several centuries or millennia besides over the scale of several decades) is through predisposing the individual to one or more behavioral patterns that favor instead of compromising the propagation of those genes it shares with (and in) a group whose members, while being not all kin-related to each other (were it only to some strong or moderate extent), still possess some level of genetic similitude allowing to speak of them as forming an extended kinship, one way the duplication of a gene or team of genes can be compromised rather than favored (in the short run besides in the long run) is through the individual’s inhabiting a society whose members, besides being not all kin-related to each other to a degree that is either complete or strong or moderate, exhibit some level of genetic similitude that is not sufficient to allowing to speak of them as forming an extended kinship.

A human society whose members exhibit neither a level of genetic similitude that allows speaking of them as forming an enlarged family nor a level of genetic similitude that allows speaking of them as forming or approaching a single family is necessarily compromising (rather than helpful) in the short as much in the long run to the duplication of the genes present in its members; regardless of whether the society in question manages to survive (over the scale of several centuries or millennia or, failing that, over the scale of several decades) and regardless of whether group-cohesion is strong in the society in question. Group-identification here means the fact of identifying oneself as a member of some group (whether the latter is real).

I assume that two instincts for group-identification successively emerged over the course of the biological evolution of homo sapiens: two instincts which are now superposed and in conflict with each other. Namely an earlier instinct for group-identification to one’s kinship—and a tardier instinct for group-identification to indeterminate groups whose level of genetic dissimilitude exceeds the level found in a kinship or in a group whose members are all kin-related to some strong or moderate extent.

At first, the tardier instinct for group-identification was a blessing (rather than a curse) to the long-run duplication of genes in humans in that it contributed (and was necessary) to the constitution of societies with a strong or complete group-cohesion who, while being not restricted to kinship nor to some strong or moderate level of kin-relatedness, exhibit a level of genetic similitude that remains strong enough to allow speaking of those societies as being extended kinships.

Over time, that instinct, thus becoming both a blessing and a curse to the duplication of genes (whether it is in the long run or in the short run), ended up contributing to the constitution of societies with a strong or complete group-cohesion who, besides being not restricted to people kin-related to an either strong or moderate or complete degree, don’t qualify either as extended kinships; what has been compromising (rather than helpful) to the duplicative success of genes in the short as much in the long run in that it has been allowing for such societies to survive in the long run (besides in the short run) at the expense of the duplicative success in question.

In the cosmos taken independently of its incarnation-relationship to God, the emergence of that second instinct for group-identification that is the instinct for group-identification to (indeterminate) groups standing below any level of kin-relatedness that is either strong or moderate or complete is only a double-edged sword to the duplication of genes; but in the cosmos as incarnation, the cosmos as God incarnated, the emergence of such instinct is also a cunning of God. More precisely, a trick on His part falling within His wider strategy of detaching the human society, if not from any enlarged kinship, at least from any strong, moderate, or complete level of kin-relatedness, in order to bring about (and experiment) unprecedentedly high and sophisticate new forms of order, complexity, in the cosmos.

Grégoire Canlorbe is an independent scholar, based in Paris. Besides conducting a series of academic interviews with social scientists, physicists, and cultural figures, he has authored a number of metapolitical and philosophical articles. He also worked on a (currently finalized) conversation book with the philosopher, Howard Bloom. See his website.

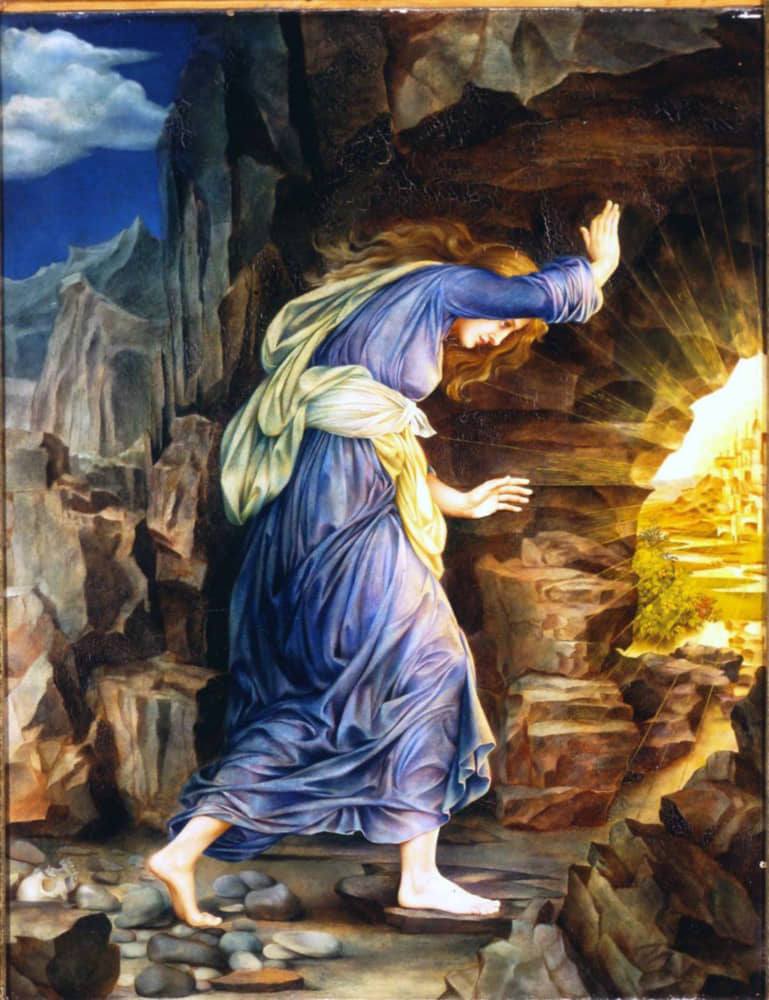

Featured image: “The Undiscovered Country/The City of Light,” by Evelyn De Morgan; painted in 1894.