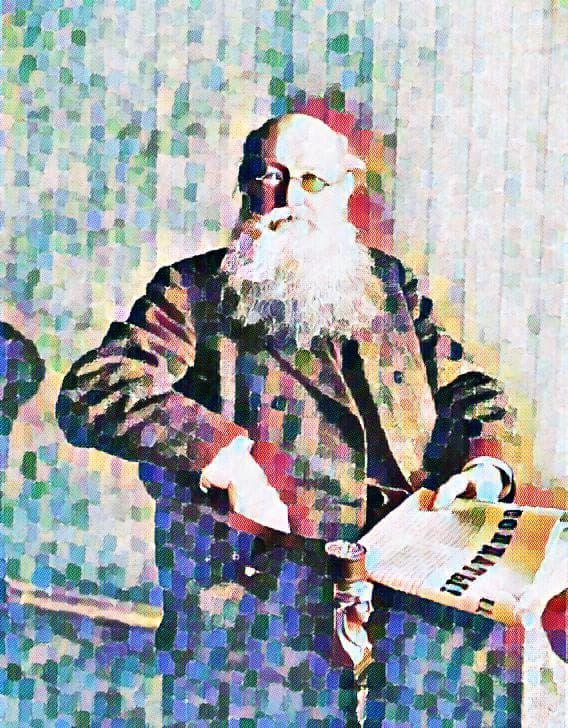

“Who are the fittest: those who are continually at war with each other, or those who support one another?” (Prince Pyotr Kropotkin, 1902).

What would happen to the accepted history of human evolution if instead of an Englishman going to the Galapagos more influence would be given to a Russian going to Siberia? Whereas Charles Darwin based his theory of Natural Selection on what he, from his cultural background, observed in the Galapagos, Pyotr Kropotkin, in his youth travelled to Siberia on geographical expeditions, where he found that a completely different vision than Darwin’s could be both observed and then transferred to the theory of human evolution. Kropotkin observed:

I saw among the semi-wild cattle and horses in Transbaikalia, among the wild ruminants everywhere, the squirrels, and so on, that when animals have to struggle against scarcity of food, in consequence of one of the above-mentioned causes, the whole of that portion of the species which is affected by the calamity, comes out of the ordeal so much impoverished in vigour and health, that no progressive evolution of the species can be based upon such periods of keen competition.

Mainly referring to animals within the same species, Kroptkin also observed in 1902:

In all these scenes of animal life which passed before my eyes, I saw Mutual Aid and Mutual Support carried on to an extent which made me suspect in it a feature of the greatest importance for the maintenance of life, the preservation of each species, and its further evolution.

Referring to Darwin’s theories of natural selection and Herbert Spencer’s addition of the notion of the survival of the fittest, he wrote:

They all endeavoured to prove that Man, owing to his higher intelligence and knowledge, may mitigate the harshness of the struggle for life between men; but they all recognized at the same time that the struggle for the means of existence, of every animal against all its congeners, and of every man against all other men, was “a law of Nature.” This view, however, I could not accept, because I was persuaded that to admit a pitiless inner war for life within each species, and to see in that war a condition of progress, was to admit something which not only had not yet been proved, but also lacked confirmation from direct observation.

Kropotkin writes about many examples of mutual aid within the animal world, including beetles, crabs, termites, ants and bees. It is the examples that come from Russia which are more culturally unique to his study, for example the Russian steppe eagle:

One of the most conclusive observations of the kind belongs to Syevertsoff. Whilst studying the fauna of the Russian Steppes, he once saw an eagle belonging to an altogether gregarious species (the white-tailed eagle, Haliactos albicilla) rising high in the air for half an hour it was describing its wide circles in silence when at once its piercing voice was heard. Its cry was soon answered by another eagle which approached it, and was followed by a third, a fourth, and so on, till nine or ten eagles came together and soon disappeared. In the afternoon, Syevertsoff went to the place whereto he saw the eagles flying; concealed by one of the undulations of the Steppe, he approached them, and discovered that they had gathered around the corpse of a horse. The old ones, which, as a rule, begin the meal first – such are their rules of propriety-already were sitting upon the haystacks of the neighbourhood and kept watch, while the younger ones were continuing the meal, surrounded by bands of crows. From this and like observations, Syevertsoff concluded that the white-tailed eagles combine for hunting; when they all have risen to a great height they are enabled, if they are ten, to survey an area of at least twenty-five miles square; and as soon as any one has discovered something, he warns the others.

From the mammals he describes the examples of cooperation within deer, antelopes, gazelles, buffaloes, wild goats, sheep, wolves, squirrels, dogs, rats, hares, rabbits, horses, donkeys, deer, wild boars, hippopotamus, rhinoceros, seals, walruses and monkeys. His observations reinforced his view that competition weakened rather than reinforced the individual species; he concluded:

Happily enough, competition is not the rule either in the animal world or in mankind. It is limited among animals to exceptional periods, and natural selection finds better fields for its activity. Better conditions are created by the elimination of competition by means of mutual aid and mutual Support. In the great struggle for life – for the greatest possible fulness and intensity of life with the least waste of energy – natural selection continually seeks out the ways precisely for avoiding competition as much as possible. The ants combine in nests and nations; they pile up their stores, they rear their cattle – and thus avoid competition; and natural selection picks out of the ants’ family the species which know best how to avoid competition, with its unavoidably deleterious consequences. Most of our birds slowly move southwards as the winter comes, or gather in numberless societies and undertake long journeys – and thus avoid competition. Many rodents fall asleep when the time comes that competition should set in; while other rodents store food for the winter, and gather in large villages for obtaining the necessary protection when at work. The reindeer, when the lichens are dry in the interior of the continent, migrate towards the sea. Buffaloes cross an immense continent in order to find plenty of food. And the beavers, when they grow numerous on a river, divide into two parties, and go, the old ones down the river, and the young ones up the river and avoid competition. And when animals can neither fall asleep, nor migrate, nor lay in stores, nor themselves grow their food like the ants, they do what the titmouse does, and what Wallace (Darwinism, ch. v) has so charmingly described: they resort to new kinds of food – and thus, again, avoid competition.

But how does this translate to human societies? Are these just observations on animal kind pushed to extremes, like the winter in Siberia, or are there lessons in there for humankind as well? Kropotkin thought there were lessons to be drawn for human evolution as well. He wrote:

Moreover, it is evident that life in societies would be utterly impossible without a corresponding development of social feelings, and, especially, of a certain collective sense of justice growing to become a habit. If every individual were constantly abusing its personal advantages without the others interfering in favour of the wronged, no society – life would be possible. And feelings of justice develop, more or less, with all gregarious animals. Whatever the distance from which the swallows or the cranes come, each one returns to the nest it has built or repaired last year. If a lazy sparrow intends appropriating the nest which a comrade is building, or even steals from it a few sprays of straw, the group interferes against the lazy comrade; and it is evident that without such interference being the rule, no nesting associations of birds could exist. Separate groups of penguins have separate resting-places and separate fishing abodes, and do not fight for them.

Kropotkin also specifically lectured in opposition to Thomas Huxley’s (the grandfather of Aldous Huxley) Evolution and Ethics lectures of 1893. Contrary to Huxley, Kropotkin believed that love, sympathy and self-sacrifice were more important than competition. In his own words:

Love, sympathy and self-sacrifice certainly play an immense part in the progressive development of our moral feelings. But it is not love and not even sympathy upon which Society is based in mankind. It is the conscience – be it only at the stage of an instinct – of human solidarity. It is the unconscious recognition of the force that is borrowed by each man from the practice of mutual aid; of the close dependency of every one’s happiness upon the happiness of all; and of the sense of justice, or equity, which brings the individual to consider the rights of every other individual as equal to his own. Upon this broad and necessary foundation the still higher moral feelings are developed.

Robin Monotti Graziadei is an architect and film producer. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Nullus locus sine genio.