1. Appearance

The term “artificial intelligence” first appeared in the 1950s, with the advent of the first computers, capable of performing certain tasks that only human intelligence had previously been able to accomplish. Computing was the very first faculty to be transferred to a machine. This explains why what we call a “computer” in English has kept its original name of computer, i.e., “calculator.” Automated calculation was the first example of artificial intelligence.

Why does calculating no longer seem to us to fall under the heading of artificial intelligence? This is an example of what the Anglo-Saxons call the “AI effect”: as artificial intelligence develops, earlier achievements are no longer regarded as artificial intelligence, but as standard machinery. Thus, for example, character recognition, fingerprint recognition and so on. In practice, then, artificial intelligence refers to what “intelligent” machines are just beginning to be able to do.

2. Downgrading the Human

When they first appeared, electronic calculators were described as “electronic brains.” Over time, as machine performance increased, the metaphor was turned on its head: it was no longer the computer that was compared to a brain, but the brain to a computer. The human being is now seen as just another “information-processing machine.” Today, the term “intelligent agent” is used to describe any “system,” natural or artificial, that interacts with its environment, draws information from it and uses this information to maximize its chances of success in achieving its goals or those assigned to it. In this context, artificial intelligence finds itself completely emancipated from the human model from which it once took its name. On the one hand, many aspects of human intelligence remain properly human. On the other hand, artificial intelligences are now capable of performances beyond the reach of any human intelligence. Although designed by humans, they are endowed with certain intellective capacities that are truly superhuman.

3. The Race for Power

Since the 19th century, technology has been indispensable to power. By technology, I am not referring to technique in general, which is as old as humanity itself, but to that very recent part of technique which is inseparable from the mathematical sciences of nature that emerged in Europe from the 17th century onwards, and is inconceivable without them. It was their technological superiority that enabled Westerners to dominate the world for a time. On the threshold of the 20th century, Hwuy-Ung, a Chinese scholar exiled in Australia, confessed his admiration for what he saw: “The marvelous inventions of this country and of Western nations are, for the most part, unknown to us, and seem incredible.” But did these wonders make people happier? The answer was not self-evident. One thing, however, was beyond doubt: “marvelous inventions” conferred unparalleled power. Hence this observation: “Those who do not follow the trend set by the most advanced nations become their victims, as we are experiencing.” After the Second World War, China set out to become a major technological power in its own right, in order to emerge from the long series of humiliations inflicted on it, from the outbreak of the first Opium War in 1839 to the Japanese invasion in 1937. Today, artificial intelligence is becoming a decisive component of technology, and if you do not want to be at the mercy of those more powerful than you, you need to invest in this field.

4. Survival in the Digital Jungle

Power is not the only issue. For as long as there have been homo sapiens on earth—some 300,000 years—they have lived most of their lives in Paleolithic conditions. It was in these conditions that the faculties of our species developed. It goes without saying that these skills include an extraordinary ability to adapt to new environments. However, since the industrial revolution, the environment in which a growing proportion of humanity is called upon to live has been changing so rapidly that, in many respects, our natural faculties, including intelligence, have been taken by surprise. If natural intelligence used to enable us to orientate ourselves correctly in the natural environment, known today as the biotope, we now need artificial intelligence to orientate ourselves correctly in an environment that is itself artificial, the technotope. And for this, artificial intelligence is indispensable. Just think, for example, how helpless we would be to use the Internet if we could not rely on search engines that incorporate forms of artificial intelligence.

5. The Control Society

Among the threats posed by the all-out development of artificial intelligence, the public’s greatest fear is undoubtedly that of social control, through the innumerable digital data now generated by our lives. After all, the word intelligence also means “information gathering.”

One thing is clear, however. By massively rejecting the old-fashioned social control constituted by the inculcation of moral rules, and the discredit that came with breaking them, by fleeing the control exercised by neighbors in traditional communities, late moderns believed that it was possible to do without social control. But a society without social control is no longer a society—it is chaos. To protect against chaos, more and more precautions have to be taken. So, for example, people living in big cities are obliged to equip themselves with digicodes, intercoms and armored doors. The more “open” society becomes, the more its members have to lock themselves in. In this respect, the automated surveillance, assisted by artificial intelligence that is taking shape, has all the allure of Nemesis, the Greek goddess who punished hubris, the excess of beings who did not respect the limits of their condition. The individual who pretended to escape all control sees control returning to him in another form.

6. Permanent Formatting

Another problem is that underneath its apparent neutrality, the machine can conceal biases that are all the more pernicious for being difficult to detect. A search engine, for example, responds to queries with lists of answers, and we do not know what went into their creation. And we do not want to know—the use of search engines would lose all interest if we had to know the details of the search itself. But this means that we are totally subject to the biases included in them, whether these biases are intentional or not. What guides us can also lead us astray, and what informs us can also manipulate us. Academics have subjected the chatbot ChatGPT to a political positioning questionnaire. The result was that OpenAI’s chatbot “has the profile of a mainstream liberal and pragmatic Californian,” very much in favor of multiculturalism, welcoming migrants or minority rights, and that if it were registered to vote in France it would probably vote Macron or Mélenchon. Let us deduce the effects of living in symbiosis with ChatGPT.

7. Looming Acedia

The development of information technology was supposed to free us from routine tasks. In fact, IT “extends the routine of its procedures everywhere.” It is feared that artificial intelligence will only intensify the process to the point of nausea. Workers who put their hearts into their work when the tasks they have to perform call on all their faculties, no longer know what meaning to give to their work when they become mere operators of machines that do the “intelligent” part of the job for them. If you take less trouble, you may also find yourself doing less well.

8. Moral Stunting

By constantly talking about artificial intelligence, making ever more use of it and marveling at its prowess, we are becoming accustomed to making artificial intelligence the paradigm of intelligence—and at the same time devaluing the essential characteristics of human intelligence, and no longer cultivating them. Long ago, God appeared to King Solomon in a dream and said: “Ask what you want me to give you.” Solomon replied, “Give your servant an intelligent heart, to govern your people, to discern between good and evil” (1Ki 3:5-9). The first character of intelligence, here, consists in discerning between good and evil. This is the intelligence that Solomon demonstrates when he dispenses justice. If we become accustomed to seeing artificial intelligence as the model of intelligence, we run the risk of leaving the heart in unintelligence.

Some will argue that it is possible to include moral considerations among the criteria taken into account by artificial intelligence in its operation. In this case, however, it is as if moral reflection had been carried out once and for all, before being delegated to the machine. A faculty that is not constantly used will wither away. Hence moral stunting.

9. Intellectual Stunting

Artificial intelligence is a product of technology, itself intrinsically linked to the development of modern science, to the constitution of mathematical sciences of nature. The aim of these sciences was to make the world comprehensible to us, while at the same time increasing our capacity to act upon it, according to the Baconian equation of knowledge = power. What is happening today?

The power we have acquired over the world has led us to transform it to such an extent that the world resulting from this transformation has become, in some respects, more opaque to us than nature of old was. Our natural faculties are overwhelmed—which is why we increasingly need artificial intelligence to find our way around it, and simply to live in it. But truly interesting artificial intelligence is that which produces results, not just faster and better than we could achieve without it, but results that escape our understanding. Artificial intelligence cannot therefore be considered as a simple decision-making tool: insofar as the genesis of the indications it gives us escapes our control, we are led to simply defer to these indications—which means, in the end, that the decision-making tool decides for us, or more precisely, that our decision resolves itself in the use of the tool. In this case, the tool does not so much increase our capabilities as completely delegate our power to an obscure tool. As a result, our intelligence, which made it possible to set up these extraordinary artificial intelligence devices, finds itself put on vacation by them; and, by dint of being on vacation, it loses the habit of work, and even the ability to work. The loss of control is not, as in a number of dystopias, linked to intelligent machines becoming malevolent towards humans and seeking to enslave or eliminate them, but to the fact that, by constantly relying on them, we become incapable, crippled.

By slouching on a sofa and playing online games, teenagers in developed countries have seen their physical capacities decline by a quarter over the last four decades. The average IQ has also fallen over the last twenty years. Many factors must be contributing to this phenomenon—but at least part of it has to do with the delegation to machines of an ever-increasing number of tasks that used to require our intelligence. At the end of the 1960s, Louis Aragon was well aware of this process: “Progress that gradually deprives me of a function leads me to lose the organ. The greater man’s ingenuity, the more he will be deprived of the physiological tools of ingenuity. His slaves of iron and wire will reach a perfection that the man of flesh has never known, while he will gradually return to the amoeba. He will forget himself.”

10. Connected Chicks

When I was a child, a playground riddle asked: what’s small, yellow and very scary? The answer was a chick with a machine gun. Today, we could ask, what’s small, yellow and thinks it’s the lord of creation? A connected chick. Connected immatures, that is what we are becoming. If the power stops flowing to the sockets, if it stops recharging the batteries, if our earthly and celestial roots are atrophied, it is not just our devices that will be neutralized, it is we ourselves that will be annihilated.

Olivier Rey is a mathematician and philosopher of science whose area of study is science and society, with a focus on transhumanism. This article appears through the kind courtesy of La Nef.

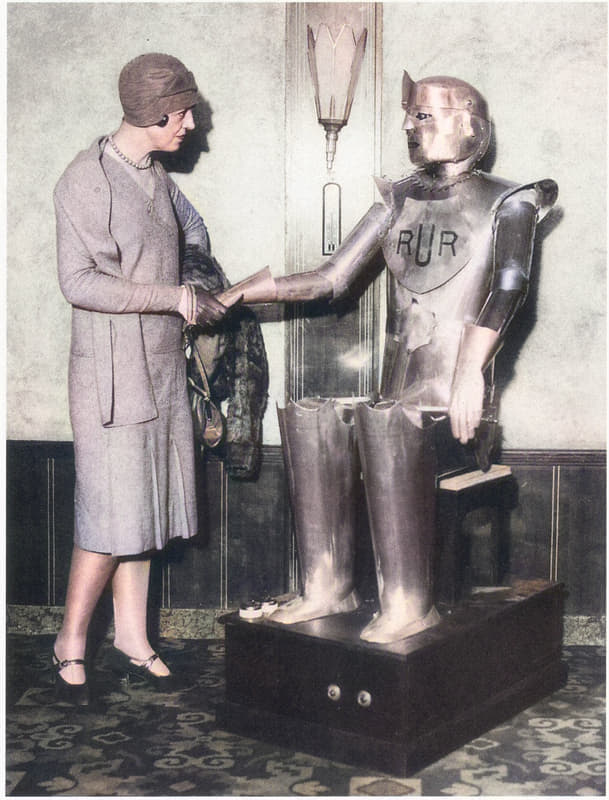

Featured: Ai-Da, the first humanoid robot, with self-portrait, 2021.