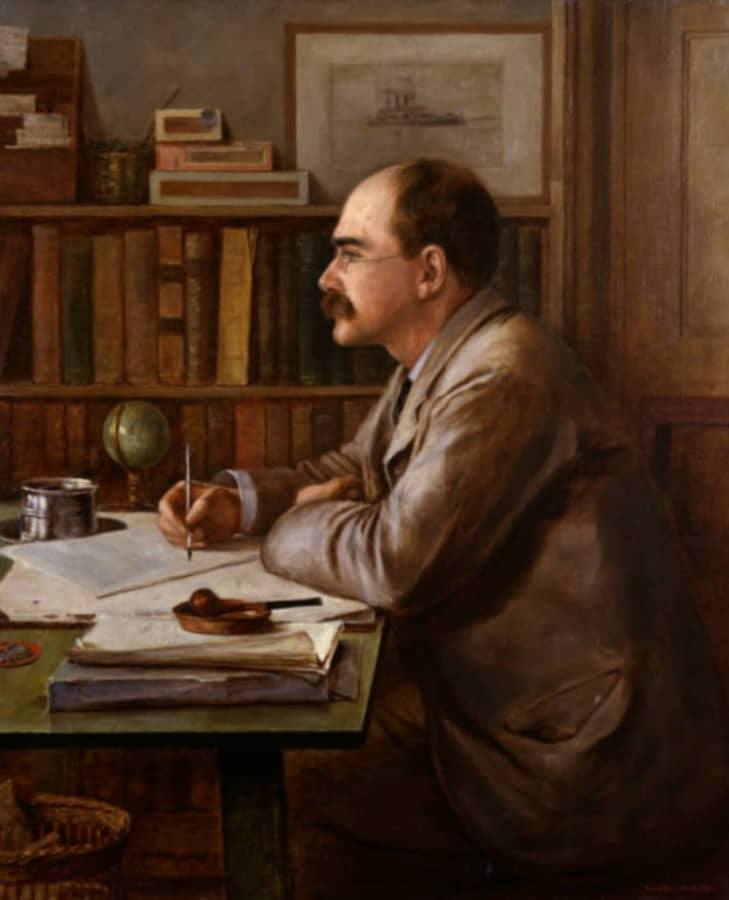

What follows is the “Introduction” to Lord Arthur Ponsonby’s famous work, Falsehood in War-Time (1928), in which he established the rules for “building” public consent, and even enthusiasm, for war.

Given that war seems to be a constant given of our highly moralistic age, it seems worthwhile to turn to works such as these to better understand how readily our minds are hijacked.

Lord Ponsonby (1871—1946) was a British politician and writer. He opposed Britain’s involvement in the First World War and worked actively for peace.

Introduction

The object of this volume is not to cast fresh blame on authorities and individuals, nor is it to expose one nation more than another to accusations of deceit. Falsehood is a recognized and extremely useful weapon in warfare, and every country uses it quite deliberately to deceive its own people, to attract neutrals, and to mislead the enemy. The ignorant and innocent masses in each country are unaware at the time that they are being misled, and when it is all over only here and there are the falsehoods discovered and exposed. As it is all past history and the desired effect has been produced by the stories and statements, no one troubles to investigate the facts and establish the truth.

Lying, as we all know, does not take place only in war-time. Man, it has been said, is not “a veridical animal,” but his habit of lying is not nearly so extraordinary as his amazing readiness to believe. It is, indeed, because of human credulity that lies flourish. But in war-time the authoritative organization of lying is not sufficiently recognized. The deception of whole peoples is not a matter which can be lightly regarded.

A useful purpose can therefore be served in the interval of so-called peace by a warning which people can examine with dispassionate calm, that the authorities in each country do, and indeed must, resort to this practice in order, first, to justify themselves by depicting the enemy as an undiluted criminal; and secondly, to inflame popular passion sufficiently to secure recruits for the continuance of the struggle. They cannot afford to tell the truth. In some cases it must be admitted that at the moment they do not know what the truth is.

The psychological factor in war is just as important as the military factor. The morale of civilians, as well as of soldiers, must be kept up to the mark. The War Offices, Admiralties, and Air Ministries look after the military side. Departments have to be created to see to the psychological side. People must never be allowed to become despondent; so victories must be exaggerated and defeats, if not concealed, at any rate minimized, and the stimulus of indignation, horror, and hatred must be assiduously and continuously pumped into the public mind by means of “propaganda.”

As Mr. Bonar Law said in an interview to the United Press of America, referring to patriotism, “It is well to have it properly stirred by German frightfulness”; and a sort of general confirmation of atrocities is given by vague phrases which avoid responsibility for the authenticity of any particular story, as when Mr. Asquith said (House of Commons, April 27, 1915) : “We shall not forget this horrible record of calculated cruelty and crime.”

The use of the weapon of falsehood is more necessary in a country where military conscription is not the law of the land than in countries where the manhood of the nation is automatically drafted into the Army, Navy, or Air Service. The public can be worked up emotionally by sham ideals. A sort of collective hysteria spreads and rises until finally it gets the better of sober people and reputable newspapers.

With a warning before them, the common people may be more on their guard when the war cloud next appears on the horizon and less disposed to accept as truth the rumours, explanations, and pronouncements issued for their consumption. They should realize that a Government which has decided on embarking on the hazardous and terrible enterprise of war must at the outset present a one-sided case in justification of its action, and cannot afford to admit in any particular whatever the smallest degree of right or reason on the part of the people it has made up its mind to fight. Facts must be distorted, relevant circumstances concealed and a picture presented which by its crude colouring will persuade the ignorant people that their Government is blameless, their cause is righteous, and that the indisputable wickedness of the enemy has been proved beyond question. A moment’s reflection would tell any reasonable person that such obvious bias cannot possibly represent the truth. But the moment’s. reflection is not allowed; lies are circulated with great rapidity. The unthinking mass accept them and by their excitement sway the rest. The amount of rubbish and humbug that pass under the name of patriotism in war-time in all countries is sufficient to make decent people blush when they are subsequently disillusioned.

At the outset the solemn asseverations of monarchs and leading statesmen in each nation that they did not want war must be placed on a par with the declarations of men who pour paraffin about a house knowing they are continually striking matches and yet assert they do not want a conflagration. This form of self-deception, which involves the deception of others, is fundamentally dishonest.

War being established as a recognized institution to be resorted to when Governments quarrel, the people are more or less prepared. They quite willingly delude themselves in order to justify their own actions. They are anxious to find an excuse for displaying their patriotism, or they are disposed to seize the opportunity for the excitement and new life of adventure which war opens out to them. So there is a sort of national wink, everyone goes forward, and the individual, in his turn, takes up lying as a patriotic duty. In the low standard of morality which prevails in war-time, such a practice appears almost innocent. His efforts are sometimes a little crude, but he does his best to follow the example set. Agents are employed by authority and encouraged in so-called propaganda work. The type which came prominently to the front in the broadcasting of falsehood at recruiting meetings is now well known. The fate which overtook at least one of the most popular of them in this country exemplifies the depth of degradation to which public opinion sinks in a war atmosphere.

With eavesdroppers, letter-openers, decipherers, telephone tappers, spies, an intercept department, a forgery department, a criminal investigation department, a propaganda department, an intelligence department, a censorship department, a ministry of information, a Press bureau, etc., the various Governments were well equipped to “instruct” their peoples.

The British official propaganda department at Crewe House, under Lord Northcliffe, was highly successful. Their methods, more especially the raining down of millions of leaflets on to the German Army, far surpassed anything undertaken by the enemy. In “The Secrets of Crewe House” by Sir Campbell Stuart, K.B.E., the methods are described for our satisfaction and approval. The declaration that only “truthful statements” were used is repeated just too often, and does not quite tally with the description of the faked letters and bogus titles and bookcovers, of which use was made. But, of course, we know that such clever propagandists are equally clever in dealing with us after the event as in dealing with the enemy at the time. In the apparently candid description of their activities we know we are hearing only part of the story. The circulators of base metal know how to use the right amount of alloy for us as well as for the enemy.

In the many tributes to the success of our propaganda from German Generals and the German Press, there is no evidence that our statements were always strictly truthful. To quote one : General von Hutier, of the Sixth German Army, sent a message in which the following passage occurs:”The method of Northcliffe at the Front is to distribute through airmen a constantly increasing number of leaflets and pamphlets; the letters of German prisoners are falsified in the most outrageous way; tracts and pamphlets are concocted, to which the names of German poets, writers, and statesmen are forged, or which present the appearance of having been printed in Germany, and bear, for example, the title of the Reclam series, when they really come from the Northcliffe press, which is working day and night for this same purpose. His thought and aim are that these forgeries, however obvious they may appear to the man who thinks twice, may suggest a doubt, even for a moment, in the minds of those who do not think for themselves, and that their confidence in their leaders, in their own strength, and in the inexhaustible resources of Germany may be shattered.”

The Propaganda, to begin with, was founded on the shifting sand of the myth of Germany’s sole responsibility. Later it became slightly confused owing to the inability of our statesmen to declare what our aims were, and towards the end it was fortified by descriptions of the magnificent, just, and righteous peace which was going to be “established on lasting foundations.” This unfortunately proved to be the greatest falsehood of all.

In calm retrospect we can appreciate better the disastrous effects of the poison of falsehood, whether officially, semiofficially, or privately manufactured. It has been rightly said that the injection of the poison of hatred into men’s minds by means of falsehood is a greater evil in wartime than the actual loss of life. The defilement of the human soul is worse than the destruction of the human body. A fuller realization of this is essential.

Another effect of the continual appearance of false and biased statement and the absorption of the lie atmosphere is that deeds of real valour, heroism, and physical endurance and genuine cases of inevitable torture and suffering are contaminated and desecrated; the wonderful comradeship of the battlefield becomes almost polluted. Lying tongues cannot speak of deeds of sacrifice to show their beauty or value. So it is that the praise bestowed on heroism by Government and Press always jars, more especially when, as is generally the case with the latter, it is accompanied by cheap and vulgar sentimentality. That is why one instinctively wishes the real heroes to remain unrecognized, so that their record may not be smirched by cynical tongues and pens so well versed in falsehood.

When war reaches such dimensions as to involve the whole nation, and when the people at its conclusion find they have gained nothing but only observe widespread calamity around them, they are inclined to become more sceptical and desire to investigate the foundations of the arguments which inspired their patriotism, inflamed their passions, and prepared them to offer the supreme sacrifice. They are curious to know why the ostensible objects for which they fought have none of them been attained, more especially if they are the victors. They are inclined to believe, with Lord Fisher, that “The nation was fooled into the war” (“London Magazine,” January 1920). They begin to wonder whether it does not rest with them to make one saying true of which they heard so much, that it was “a war to end war.”

When the generation that has known war is still alive, it is well that they should be given chapter and verse with regard to some of the best-known cries, catchwords, and exhortations by which they were so greatly influenced. As a warning, therefore, this collection is made. It constitutes only the exposure of a few samples. To cover the whole ground would be impossible. There must have been more deliberate lying in the world from 1914 to 1918 than in any other period of the world’s history.

There are several different sorts of disguises which falsehood can take. There is the deliberate official lie, issued either to delude the people at home or to mislead the enemy abroad; of this, several instances are given. As a Frenchman has said: ” Tant que les peuples seront armés, les uns contre les autres, ils auront des hommes d’état menteurs, comme ils auront des canons et des mitrailleuses.” (“As long as the peoples are armed against each other, there will be lying statesmen, just as there will be cannons and machine guns.”)

A circular was issued by the War Office inviting reports on war incidents from officers with regard to the enemy and stating that strict accuracy was not essential so long as there was inherent probability.

There is the deliberate lie concocted by an ingenious mind which may only reach a small circle, but which, if sufficiently graphic and picturesque, may be caught up and spread broadcast ; and there is the hysterical hallucination on the part of weak-minded individuals.

There is the lie heard and not denied, although lacking in evidence, and then repeated or allowed to circulate.

There is the mistranslation, occasionally originating in a genuine mistake, but more often deliberate. Two minor instances of this may be given.

The Times (agony column), July 9, 1915:

Jack F. G. — If you are not in khaki by the 20th, 1 shall cut you dead.—ETHEL M.

The Berlin correspondent of the Cologne Gazette transmitted this :

If you are not in khaki by the 20th, hacke ich dich zu Tode (I will hack you to death).

During the blockade of Germany, it was suggested that the diseases from which children suffered had been called Die englische Krankheit, as a permanent reflection on English inhumanity. As a matter of fact, die englische Krankheit is, and always has been, the common German name for rickets.

There is the general obsession, started by rumour and magnified by repetition and elaborated by hysteria, which at last gains general acceptance.

There is the deliberate forgery which has to be very carefully manufactured but serves its purpose at the moment, even though it be eventually exposed.

There is the omission of passages from official documents of which only a few of the many instances are given; and the “correctness” of words and commas in parliamentary answers which conceal evasions of the truth.

There is deliberate exaggeration, such, for instance, as the reports of the destruction of Louvain :

“The intellectual metropolis of the Low Countries since the fifteenth century is now no more than a heap of ashes” (Press Bureau, August 29, 1914),

“Louvain has ceased to exist” (The Times, August 29th , 1914).

As a matter of fact, it was estimated that about an eighth of the town had suffered.

There is the concealment of truth, which has to be resorted to so as to prevent anything to the credit of the enemy reaching the public. A war correspondent who mentioned some chivalrous act that a German had done to an Englishman during an action received a rebuking telegram from his employer: “Don’t want to hear about any good Germans”; and Sir Philip Gibbs, in Realities of War, says: “At the close of the day the Germans acted with chivalry, which I was not allowed to tell at the time.”

There is the faked photograph (“the camera cannot lie “). These were more popular in France than here. In Vienna an enterprising firm supplied atrocity photographs with blanks for the headings so that they might be used for propaganda purposes by either side.

The cinema also played a very important part, especially in neutral countries, and helped considerably in turning opinion in America in favour of coming in on the side of the Allies. To this day in this country attempts are made by means of films to keep the wound raw.

There is the “Russian scandal,” the best instance of which during the war, curiously enough, was the rumour of the passage of Russian troops through Britain. Some trivial and imperfectly understood statement of fact becomes magnified into enormous proportions by constant repetition from one person to another.

Atrocity lies were the most popular of all, especially in this country and America; no war can be without them. Slander of the enemy is esteemed a patriotic duty. An English soldier wrote (“The Times,” September 15, 1914) : “The stories in our papers are only exceptions. There are people like them in every army.” But at the earliest possible moment stories of the maltreatment of prisoners have to be circulated deliberately in order to prevent surrenders. This is done, of course, on both sides. Whereas naturally each side tries to treat its prisoners as well as possible so as to attract others.

The repetition of a single instance of cruelty and its exaggeration can be distorted into a prevailing habit on the part of the enemy. Unconsciously each one passes it on with trimmings and yet tries to persuade himself that he is speaking the truth.

There are lies emanating from the inherent unreliability and fallibility of human testimony. No two people can relate the occurrence of a street accident so as to make the two stories tally. When bias and emotion are introduced, human testimony becomes quite valueless. In war-time such testimony is accepted as conclusive. The scrappiest and most unreliable evidence is sufficient — “the friend of the brother of a man who was killed.” or, as a German investigator of his own liars puts it, “somebody who had seen it,” or, “an extremely respectable old woman.”

There is pure romance. Letters of soldiers who whiled away the days and weeks of intolerable waiting by writing home sometimes contained thrilling descriptions of engagements and adventures which had never occurred.

There are evasions, concealments, and half-truths which are more subtly misleading and gradually become a governmental habit.

There is official secrecy which must necessarily mislead public opinion. For instance, a popular English author, who was perhaps better informed than the majority of the public, wrote a letter to an American author, which was reproduced in the Press on May 21st , 19 18, stating:

“There are no Secret Treaties of any kind in which this country is concerned. It has been publicly and clearly stated more than once by our Foreign Minister, and apart from honour it would be political suicide for any British official to make a false statement of the kind.”

Yet a series of Secret Treaties existed. It is only fair to say that the author, not the Foreign Secretary, is the liar here. Nevertheless the official pamphlet, The Truth about the Secret Treaties, compiled by Mr. McCurdy, was published with a number of un-acknowledged excisions, and both Lord Robert Cecil, in 1917 and Mr. Lloyd George in 1918 declared (the latter to a deputation from the Trade Union Congress) that our policy was not directed to the disruption of Austro-Hungary, although they both knew that under the Secret Treaty concluded with Italy in April 1918 portions of Austria-Hungary were to be handed over to Italy and she was to be cut off from the sea. Secret Treaties naturally involve constant denials of the truth.

There is sham official indignation depending on genuine popular indignation which is a form of falsehood sometimes resorted to in an unguarded moment and subsequently regretted. The first use of gas by the Germans and the submarine warfare are good instances of this.

Contempt for the enemy, if illustrated, can prove to he an unwise form of falsehood. There was a time when German soldiers were popularly represented cringing, with their arms in the air and crying “Kamerad,” until it occurred to Press and propaganda authorities that people were asking why, if this was the sort of material we were fighting against, had we not wiped them off the field in a few weeks.

There are personal accusations and false charges made in a prejudiced war atmosphere to discredit persons who refuse to adopt the orthodox attitude towards war.

There are lying recriminations between one country and another. For instance, the Germans were accused of having engineered the Armenian massacres, and they, on their side, declared the Armenians, stimulated by the Russians, had killed 150,000 Mohammedans (Germania, October 9, 1915).

Other varieties of falsehood more subtle and elusive might be found, but the above pretty well cover the ground.

A good deal depends on the quality of the lie. You must have intellectual lies for intellectual people and crude lies for popular consumption, but if your popular lies are too blatant and your more intellectual section are shocked and see through them, they may (and indeed they did) begin to be suspicious as to whether they were not being hoodwinked too. Nevertheless, the inmates of colleges are just as credulous as the inmates of the slums.

Perhaps nothing did more to impress the public mind — and this is true in all countries —- than the assistance given in propaganda by intellectuals and literary notables. They were able to clothe the tough tissue of falsehood with phrases of literary merit and passages of eloquence better than the statesmen. Sometimes by expressions of spurious impartiality, at other times by rhetorical indignation, they could by their literary skill give this or that lie the stamp of indubitable authenticity, even without the shadow of a proof, or incidentally refer to it as an accepted fact. The narrowest patriotism could be made to appear noble, the foulest accusations could be represented as an indignant outburst of humanitarianism, and the meanest and most vindictive aims falsely disguised as idealism. Everything was legitimate which could make the soldiers go on fighting.

The frantic activity of ecclesiastics in recruiting by means of war propaganda made so deep an impression on the public mind that little comment on it is needed here. The few who courageously stood out became marked men. The resultant and significant loss of spiritual influence by the Churches is, in itself, sufficient evidence of the reaction against the betrayal in time of stress of the most elementary precepts of Christianity by those specially entrusted with the moral welfare of the people.

War is fought in this fog of falsehood, a great deal of it undiscovered and accepted as truth. The fog arises from fear and is fed by panic. Any attempt to doubt or deny even the most fantastic story has to be condemned at once as unpatriotic, if not traitorous. This allows a free field for the rapid spread of lies. If they were only used to deceive the enemy in the game of war it would not be worth troubling about. But, as the purpose of most of them is to fan indignation and induce the flower of the country’s youth to be ready to make the supreme sacrifice, it becomes a serious matter. Exposure, therefore, may be useful, even when the struggle is over, in order to show up the fraud, hypocrisy, and humbug on which all war rests, and the blatant and vulgar devices which have been used for so long to prevent the poor ignorant people from realizing the true meaning of war.

It must be admitted that many people were conscious and willing dupes. But many more were unconscious and were sincere in their patriotic zeal. Finding now that elaborately and carefully staged deceptions were practised on them, they feel a resentment which has not only served to open their eyes but may induce them to make their children keep their eyes open when next the bugle sounds.

Let us attempt a very faint and inadequate analogy between the conduct of nations and the conduct of individuals.

Imagine two large country houses containing large families with friends and relations. When the members of the family of the one house stay in the other, the butler is instructed to open all the letters they receive and send and inform the host of their contents, to listen at the keyhole, and tap the telephone. When a great match, say a cricket match, which excites the whole district, is played between them, those who are present are given false reports of the game to them think the side they favour is winning, the other side is accused of cheating and foul play, and scandalous reports are circulated about the head of the family the hideous goings on in the other house.

All this, of course, is very mild, and there would no specially dire consequences if people were to be in such an inconceivably caddish, low, and underhand way, except that they would at once be expelled from decent society.

But between nations, where the consequences are vital, where the destiny of countries and provinces hangs in the balance, the lives and fortunes of millions are affected and civilization itself is menaced, the most upright men honestly believe that there is no depth of duplicity to which they may not legitimately stoop. They have got to do it. The thing cannot go on without the help of lies.

This is no plea that lies should not be used in time, but a demonstration of how lies must be us in war-time. If the truth were told from the start there would be no reason and no will for war.

Anyone declaring the truth: “Whether you right or wrong, whether you win or lose, in no circumstances can war help you or your country,” would himself in gaol very quickly. . In wartime, failure of a lie is negligence, the doubting of a lie a misdemeanour, the declaration of the truth a crime.

In future wars we have now to look forward to a new and far more efficient instrument of propaganda – the Government control of broadcasting. Whereas therefore, in the past we have used the word “broadcast” symbolically as meaning the efforts of the Press and individual reporters, in future we must use the word literally, since falsehood can now be circulated universally, scientifically, and authoritatively.

Many of the samples given in the assortment are international, but some are exclusively British, as these are more easily found and investigated, and, after all, we are more concerned with our own Government and Press methods and our own national honour than with the duplicity of other Governments.

Lies told in other countries are also dealt with in cases where it has been possible to collect sufficient data. Without special investigation on the spot, the career of particular lies cannot be fully set out.

When the people of one country understand how the people in another country are duped, like themselves, in wartime, they will be more disposed to sympathize with them as victims than condemn them as criminals, because they will understand that their crime only consisted in obedience to the dictates of authority and acceptance of what their Government and Press represented to them as the truth.

The period covered is roughly the four years of the war., The intensity of the lying was mitigated after 1918, although fresh crops came up in connection with other of our international relations. The mischief done by the false cry “Make Germany pay” continued after 1918 and led, more especially in France, to high expectations and consequent indignation when it was found that the people who raised this slogan knew all the time it was a fantastic impossibility. Many of the old war lies survived for several years, and some survive even to this day.

There is nothing sensational in the way of revelations contained in these pages. All the cases mentioned are well known to those who were in authority, less well known to those primarily affected, and unknown, unfortunately, to the millions who fell. Although only a small part of the vast field of falsehood is covered, it may suffice to show how the unsuspecting innocence of the masses in all countries was ruthlessly and systematically exploited.

There are some who object to war because of its immorality, there are some who shrink from the arbitrament of arms because of its increased cruelty and barbarity; there are a growing number who protest against this method, at the outset known to be unsuccessful, of attempting to settle international disputes because of its imbecility and futility. But there is not a living soul in any country who does not deeply resent having his passions roused, his indignation inflamed, his patriotism exploited, and his highest ideals desecrated by concealment, subterfuge, fraud, falsehood, trickery, and deliberate lying on the part of those in whom he is taught to repose confidence and to whom he is enjoined to pay respect.

None of the heroes prepared for suffering and sacrifice, none of the common herd ready for service and obedience, will be inclined to listen to the call of their country once they discover the polluted sources from whence that call proceeds and recognize the monstrous finger of falsehood which beckons them to the battlefield.