Few Americans know much about Francisco Franco, leader of the winning side in the Spanish Civil War and subsequently dictator of Spain. Yet from 1936 until 1975, he was a famous world figure. Now he is forgotten—but not by all. Franco is, and has been for decades, a cause célèbre among the global Left, seen as the devil incarnate for his successful war against Communist domination of Spain.

To successfully delay, or worse, block, any Left attempt to establish their permanent rule, thereby revealing that history lacks a progressive direction, is the unforgivable sin. Naturally, therefore, my own impression of Franco was generally favorable. But after reading up on him, my impression of him has changed. Now it is positively glowing.

It is very difficult to grasp the controversial figures of the past century. By “controversial,” I mean right-wing, since no prominent left-wing figure is ever deemed, in the common imagination formed by the left-wing dominance of academia and media, to be “controversial.” Instead, such people are “bold” or “courageous.”

The only way to get at the truth about a right-wing figure is to absorb a great many facts about him. It doesn’t matter much if the facts are slanted, or are disputed, or even if lies are told, as they always are about any right-wing figure. Reading enough detail allows the truth to come into focus, which mostly means ferreting out where the Left is lying or where one’s impression has been formed by propaganda or half-truths.

Even though facts matter most, the first thing to do when reading a book about any right-wing figure, or any event or happening important to the Left, is to check the political angle of the author, to know the likely slant. Somewhat surprisingly, most recent popular English-language general histories of the Spanish Civil War are only modestly tilted Left.

The best-known is that by Hugh Thomas (recently deceased and a fantastic writer, mostly on Spain’s earlier history), which I’ve read; Antony Beevor, specialist in popularized histories of twentieth-century war, also wrote one, which I have skimmed. Several others exist, and voluminous Spanish-language literature, as well, about which I know essentially nothing other than as cited in English-language texts.

Reading biographies of Franco, rather than histories of the Civil War, pulls back the lens to see Spain across the first three-quarters of the twentieth century, not just in the years between 1936 and 1939. Any history revolving around Franco in that period is necessarily both a history of Spain and the history of Left-Right conflict.

This is useful because my purpose is not just to understand Franco, although that’s interesting enough, but what Franco and his times say for our times. While my initial intention was just to read one biography, it quickly became clear that more detail would allow more clarity. I deemed this amount of effort important because I think the Spanish experience in the twentieth century has a lot to say to us.

Therefore, I selected three biographies. The first was Franco: A Personal and Political Biography, published in 2014, by Stanley Payne, a professor at the University of Wisconsin. Payne has spent his entire long career writing many books on this era of Spain’s history, and he is also apparently regarded as one of the, if not the, leading experts on the typology of European fascism. Payne’s treatment of Franco is straight up the middle, neither pro nor con, and betrays neither a Left nor Right bias—although, to be sure, a straightforward portrait contradicts the Left narrative, and thus can be seen as effectively tilted Right, whatever the author’s actual intentions.

The second was Spanish historian Enrique Moradiellos’s 2018 Franco: Anatomy of a Dictator, a shorter treatment generally somewhat negative with respect to Franco.

The third, Franco: A Biography, was by Paul Preston, a professor at the London School of Economics, who like Payne is an expert in twentieth-century Spain. Unlike Payne, or Moradiellos, he is an avowed political partisan, of the Left, and his 1993 biography of Franco is vituperative, but it was also the first major English-language study of Franco, and is regarded as a landmark achievement offering enormous detail, even if it is superseded in some ways by later scholarship.

Preston also published, in 2012, the dubiously named, The Spanish Holocaust, analyzing through a hard-Left lens the killings of the Civil War, which I have read in part and to which I will also refer.

In addition, I have consulted a variety of other books, including Julius Ruiz’s recent work on the Red Terror in Madrid, and repeatedly viewed the five-hour 1983 series The Spanish Civil War, produced in the United Kingdom and narrated by Frank Finlay, available on YouTube, which while it has a clear left-wing bias, offers interviews with many actual participants in the war.

Unlike my usual technique, which is to review individual books and use them as springboards for thought, I am trying something new. I am writing a three-part evaluation of twentieth-century Spain, through a political lens, in which I intend to sequentially, but separately, focus on three different time periods.

First, the run-up to the Civil War. Second, the war itself, mainly with respect to its political, not military, aspects, and its immediate aftermath. Third, Franco’s nearly forty years as dictator, and the years directly after.

Using multiple books from multiple political angles will highlight areas of contradiction or dispute, and allow tighter focus on them. True, I have not read any actually pro-Franco books—I would, but, as Payne notes, there are no such English-language books, though he mentions several in Spanish.

The American (and English) Right has always been very reticent about any endorsement of Franco. Part of this is the result of ignorance combined with the successful decades-long propaganda campaign of the Left. If you’re ill-informed, it’s easy to lump Franco in with Hitler, or if you’re feeling charitable, Mussolini, and who wants to associate himself with them?

Part of it is the inculcated taste for being a beautiful loser, on sharp display for some reason among modern English conservatives, not only Peter Hitchens in his book The Abolition of Britain but also Roger Scruton in How To Be A Conservative. But a bigger part, I think, is distaste for the savagery of civil wars, combined with the feeling that Christians should not kill their enemies, except perhaps in open battle in a just war.

On the surface, this seeming pacifism appears to be a standard thread of Christian thought. But examined more closely, it is actually a new claim, since the contested dividing line has always been if and under what circumstances killing in self-defense is permitted. Whether the killing occurs in the heat of battle is a mere happenstance, now incorrectly elevated by some on the Right to the core matter, probably as a backdoor way of limiting killing by the state. The effect, though, is to repudiate killing in self-defense outside of battle, even by the authorities, ignoring the admonition of Saint Paul, that the ruler “beareth not the sword in vain: for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil.”

Competently illustrating this weak-kneed and incoherent line of thought among the modern Right, Peter Hitchens wrote a recent piece in First Things about Franco. Hitchens was, in fact, also reviewing Moradellios’s book, and his review exquisitely demonstrates this intellectual confusion and theological incoherence.

He goes on at great length about the evils of the Republicans and how their victory would have been disastrous for Spain. But then he goes on at greater length telling us that Christians cannot look to Franco, because he committed “crimes,” none of which are specified in the review (or, for that matter, in the book being reviewed), probably because to specify them would make them seem not very crime-like.

We must therefore reject Franco, Hitchens tells us, for an unspecified alternative that was most definitely not on offer in 1936, and is probably not going to be on offer if, in the future, we are faced with similar circumstances.

This is foolishness. (It is not helped by Hitchens’s self-focus and his repeated attempts to establish his own personal intellectual superiority, sniffing, for example, that Franco watched television and “had no personal library,” though if Hitchens had read Payne, he would know that was because the Republicans destroyed it in 1936). And Hitchens whines that Franco “hardly ever said or wrote anything interesting in his life,” which is false (and if true would be irrelevant), though in part explained by Franco’s oft-repeated dictum that “One is a slave to what one says but the owner of one’s silence.”

Hitchens squirms a bit, though, when he (at least being intellectually honest) quotes Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s ringing endorsement of Franco. “I saw that Franco had made a heroic and colossal attempt to save his country from disintegration. With this understanding there also came amazement: there had been destruction all around, but with firm tactics Franco had managed to have Spain sidestep the Second World War without involving itself, and for twenty, thirty, thirty-five years, had kept Spain Christian against all history’s laws of decline! But then in the thirty-seventh year of his rule he died, dying to a chorus of nasty jeers from the European socialists, radicals, and liberals.”

Hitchens, for no stated reason, seems to think that Moradiellos’s book proves Solzhenitsyn wrong, when the exact opposite is the case. Hitchens even ascribes Solzhenitsyn’s praise to “infatuation on the rebound,” whatever that means, though the quote is from the late 1970s (from the recently released autobiography, Between Two Millstones), long after Solzhenitsyn’s experiences in the Gulag.

Probably realizing how weak his argument is, Hitchens then switches gears without acknowledging it, dropping the “crimes” line and claiming that since Franco’s work was all undone rapidly after his death, Franco was bad. Which is even more intellectually sieve-like.

The lack of mental rigor in this line of thought can be seen if we switch the focus from Franco to any one of scores of Christian heroes of the past. Once you leave Saint Francis of Assisi behind, any Christian military hero plucked at random from the pages of history did far worse things to his enemies, and often to his friends, than Franco.

Try Charlemagne. Or Saint Louis IX. Or Richard II Lionheart. Or El Cid. Or Don Juan of Austria. All wars fought to decide ultimate questions are unpleasant and involve acts that endanger the souls of men. It is merely the proximity of Franco to us in time, combined with the lack of steel that has affected many Christians for decades now, that makes Hitchens shrink from endorsing Franco and his deeds, all his deeds.

In two hundred years if, God willing, the Left and its Enlightenment principles are nothing but a faded memory and a cautionary tale, Hitchens’s complaints will seem utterly bizarre, like a belief that the Amazons were real. Would I care to stand in Franco’s shoes before the judgment seat of Christ? Not particularly. But I am far from certain that it would be an uncomfortable position.

Several events appear in every history of the Spanish Civil War. Among these are the 1930 Jaca revolt; the 1934 Asturias Rebellion; and the 1937 bombing of Guernica.

In astronomy, there is the concept of “standard candles.” These are stars of a known luminosity, whose distance can be accurately calculated, and against which other celestial objects can then be measured. I think of events that regularly recur in histories as standard candles: happenings about which certain facts are not in dispute, but which different authors approach differently, either by emphasizing or omitting certain facts.

By examining each author’s variations, we can measure him against the standard candles, determining, to some degree, whether his history is objective, or a polemic, in which latter case its reliability becomes suspect.

The Run-Up

For many Americans, the thought of historical Spain conjures up images of ships carrying gold across the ocean, or for the literary and somewhat confused, Don Quixote riding with his lance across a dusty plain. But in 1892, Spain was a country with no gold and no knights, though plenty of farmers. Franco was born in that year into a naval family, when the Spanish military, and particularly the navy, had also fallen far from its former glory (in part the result of recent defeat by America in the Spanish-American War).

Not a promising physical specimen, he enrolled as an infantry cadet at fourteen. He asked to be posted to Spanish Morocco, the only place Spain had any fighting military, and went there at nineteen, quickly establishing himself as a courageous, unflappable leader of men, as well as a disciplinarian and martinet.

Franco asked for the most dangerous assignments (of the forty-two officers assigned to the “shock” troops in 1912, only seven were alive by 1915), and his mostly Muslim soldiers were in superstitious awe of his luck. His luck wasn’t perfect—he was gut shot by a machine gun, and only survived because the bullet happened to miss all his organs, a most unlikely event. But even that contributed to Franco’s reputation, and to his own later belief in his providential mission.

All this brought much attention from the prominent, including the King, Alfonso XIII (Spain was a parliamentary monarchy at the time), and rapid promotion. Although Spain was politically in turmoil during these years, Franco (like most officers in the Spanish military) was strictly non-political. He married in 1923 (and unlike most men of power, was unfailingly faithful to his wife his entire life). Continuing his service in Morocco, he was promoted to general in 1926, at thirty-three the youngest general in Europe—though by European standards, he had little modern war experience.

He never commanded more than a brigade, and experienced only relatively primitive warfare with relatively primitive weapons, since the Spanish military was never well-equipped. After being promoted, he “retired” from combat, becoming director of Spain’s main military academy, until 1931.

It was toward the end of this period that politics became impossible for Franco to ignore. In 1930, the Spanish left-wing parties all managed to ally under the Pact of San Sebastián, collectively adopting the label “Republican” to denote their left-wing goals, a nomenclature that stuck, and agreeing to overthrow the monarchy by any means necessary.

This is the origin of the term Republican as denoting one side in the Civil War; it means both revolutionary leftist and necessarily exclusionary of any non-left parties, rather than being derived from “republican,” meaning devoted to representative government. (For this reason, Payne uses the terms “Republican” and “revolutionary” interchangeably in his book.) Even among this group of Leftists, there was a range of opinion (ignoring the outlier viewpoint of the Catalan separatists, who were also involved).

The key principle, as with all such groupings, was that there could be no enemies to the Left, and no compromise with the Right; total power to the Left and the disenfranchisement of the Right was the permanent goal.

After the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera, which lasted from 1923 to 1930, was succeeded by the even softer dictatorship of Dámaso Berenguer, the Republicans quickly initiated their first political violence, a small military revolt, the “Jaca revolt.” The revolt was put down quickly, but not before the Republican rebels had killed several other soldiers who refused to join them. (One of the Republicans involved, though not in the killing, was Franco’s brother Ramón, a political radical who fled Spain as a result, but who returned later to fight for Franco, and died in the war).

As Payne notes, “These totally unprovoked killings opened the steadily accelerating cycle of leftist violence in Spain that would eventually bring civil war.” That was the goal, naturally—one theme of Payne is that the Left wanted civil war, figuring they would win and that would cement their power permanently, since, as Moradiellos points out, Spain was not only sharply divided, but without any group having notably more power than the others, such that the result was political deadlock without some deus ex machina.

The Jaca revolt is revealing, and usable as a standard candle, because as the earliest such event, it begins to show the pattern of ideological distortion found in different histories. At least in the mainstream, English-language works I have read, there is little dispute as to facts.

But what you find is that the left-leaning authors, Preston in particular, solve the problem of inconvenient facts by simply omitting them. So, here, Preston never mentions that the rebels killed anyone; they were unjustly executed as “mutineers,” and their subsequent adulation as Republican martyrs is portrayed as entirely reasonable.

In 1931, the monarchy ended and the Second Republic was declared. This wasn’t the result of any democratic process, but the result of the total collapse of support for the monarchy from its traditional supporters at the same time the Republicans had prepared to seize power, combined with the King’s unwillingness to risk civil war. In practice, the first government of the Second Republic was merely the self-named “revolutionary committee” of the Republicans.

But despite these unpromising beginnings, and the open participation of many anti-democratic, revolutionary elements, the Second Republic managed, at the beginning, to be actually republican, more liberal than leftist, though there were plenty of leftist actions taken, most prominently open violence against the Church and extensive anti-religious legal measures, along with open persecution of the religious.

Preston ignores all this, referring instead to the “hysteria” (one of his favorite words) of anyone opposed to leftist hegemony. Still, as Payne notes, the first Republican government, under the “left Republican” Prime Minister Manuel Azaña, “held that the Republic must be a completely leftist regime under which no conservative party or coalition could be accepted as a legitimate government, even in the remote possibility that one were democratically elected. . . . Such an attitude made the development of a genuinely liberal democratic regime almost impossible.”

To anyone paying attention, this is merely the usual tactic of the Left—the ratchet must only go one way. It can go Left, but however far Left it goes, it can never go any less Left, no matter how many democratic votes the Right gets. If the Right threatens to disturb the ratchet, violence is the acceptable solution to keep Left dominance.

Until recently, this was a purely Continental phenomenon; its most recent manifestations have shown up in France (with the National Rally, what was the Front National) and in Sweden (with the Sweden Democrats). Since 2017, it has shown up in the United States, as a reaction to Donald Trump daring to actually try to govern in a conservative fashion, something no Republican had tried to do since Calvin Coolidge.

The same beginning low-level violence led by the Left against the Right is already in evidence here, as well, unfortunately (as well as occasional higher-level political violence, such as James Hodgkinson’s attempted assassination of the Republican Congressional leadership, which has been memory-holed by the Left using its control of the media—one difference between then and now, as I discuss below, is that the Left now controls far more of the levers of power).

Political violence was the new norm in 1930s Spain. Payne estimates that nearly 2,500 lives were lost to political violence from 1931 until the beginning of the Civil War in 1936. Most of those people were killed by the Left, but not all, and both sides tended to dehumanize the other side, though again the Left led here—as Payne notes, early on one of the favorite Republican words was “extermination.”

Here again, we see this type of language rising on the mainstream American Left—last month Democratic freshman Representative Ilhan Omar, the bigoted new flower child of American progressives, publicly referred to Donald Trump as “not human,” and prominent Democrat Paul Begala publicly called Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner “cockroaches” and “a different kind of species,” in both cases without any apology or consequences.

One might object, if one were a Leftist offended by the truth, that there is also right-wing political violence in America today, adducing, say, Dylann Roof killing black church parishioners in 2015, or, stretching abroad, last month’s killing of mosque worshippers in New Zealand. You have to draw a pretty big circle to claim those killers are “right-wing,” but it’s not totally implausible. They certainly weren’t left-wing, in any reasonable read of their confused politics.

Still, the “political” angle, and tie to concrete politics, of Hodgkinson was far more evident. But the key difference, that makes right-wing high-profile attacks different, is that Hodgkinson was part of the ecosystem of the Left, and the right-wing killers were not part of the ecosystem of the Right.

Such killers being part of the Left ecosystem is a necessary consequence of the mandatory Left principle that there are no enemies to the Left; you cannot plausibly maintain both that principle and that you are not responsible for fringe actions, and Hodgkinson was merely following the very many open calls for violence after Trump’s election by progressive leaders, none of whom even thought once about apologizing or trying to dial back their violent rhetoric afterwards. (In the Spanish context there was even less ambiguity—all Left violence was an acknowledged part of the Left program; the question was only whether any particular act was prudent).

On today’s American Right, which aggressively polices its borders (probably too aggressively), there is no legitimate claim that the Right in general is responsible for fringe actions. Which is not to say that, with the Internet and the persecution of conservatives, that such fringe actions will not occur more often, as sociopaths seek meaning and transcendence through violence.

Naturally, the Leftist media inverts this reality, without any claim to logic or reason, in order to attack the Right and wholly excuse the Left. In the fevered imaginations of the Left, or so they claim, murderous white supremacists, for example, are key and important components of the American Right.

But the true reality is inevitable and inescapable. Just as inescapable is leftist propaganda and lies, for exaggerating right-wing violence and demanding a response from the Right is both a successful way to ask a “have you stopped beating your wife?” question and a way to avoid talking about the evils of the Left. They offer not reasoning or argument, but shrieks that the Right must abase itself and surrender for no apparent reason other than that it is desired by the Left. The correct response is simply to refuse to engage in such discussions, and instead demand the Left clean its own stables.

However, this entire analysis is somewhat beside the point, because it ignores that high-profile political violence, whether of Hodgkinson or Roof, is not the core of political violence today. Such violence may be, as it became in Spain, the main event. But today the core of political violence is rather the daily violence visited exclusively today by the American Left on the Right, on the streets, in restaurants, and in schools. And that core is what will, and should, cause a justified reaction on the Right, at which point violence will likely become part of the ecosystem of both Left and Right, though the fault will lie primarily with the Left, as always.

Anyway, back in Spain and eighty years ago, the Azaña government also immediately implemented another inexorable feature of leftist rule, the legal prosecution of their political opponents—in this case, those who served under the monarchy during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, and those involved in prosecuting the “Jaca martyrs.”

The euphemism for this was the “responsibilities program.” (Yet again, we see this occurring in the United States, with the witch hunt against Trump and his associates, and when the Democrats regain executive power, we will doubtless see an enormous explosion of such prosecutions, as well as a growing number of state-level attacks, both of which grew lushly under Obama).

Some military men fell before these attacks, but Franco, although he was prominent, was well known to never engage in politics, so he was not attacked. Still, he was demoted and ostracized by the new government, which (correctly) saw that his basic orientation was conservative.

Franco took no part whatsoever, however, in the failed 1932 revolt led by General José Sanjurjo, subsequent to which the Republicans arrested thousands of conservatives and closed hundreds of newspapers, and continued their policy of blocking conservative political meetings and generally obstructing Right political action, though Sanjurjo himself escaped, to play a part in the Civil War. (Such activity has its modern parallel in the shutting down of conservative speeches across the nation, by violence with government complicity, and the massive and expanding coordinated deplatforming of conservatives from the public utilities that are the main method of communication in America today).

Seen, therefore, as generally reliable, Franco was appointed commander of the strategic Balearic Islands, where, in his leisure time, he began to become more politicized, though not visibly. The main targets of his ire were a perceived conspiracy among Freemasons, big business, and finance capital, which, if you leave out the Freemasons, makes him not dissimilar to Tucker Carlson. (Anti-Semitism was not part of this; Franco was not, then or later, in the least anti-Semitic as an ideological position, and probably no more personally anti-Semitic than, say, Franklin Roosevelt).

A new center-right party, the CEDA, gained political ground. In the 1933 elections, in a trial run for 1936, violence was used to suppress the CEDA vote, and when the CEDA got the most votes and was the largest party in parliament, the Republicans attempted to simply cancel the results. While the president, Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, a Leftist somewhat more moderate than most Republicans, though an active participant in the Pact of San Sebastián, declined to comply with his fellow Leftists’ demands (there was always a spectrum on the Spanish Left), he ensured that the CEDA was barred from any participation in the government and denied any share of political power. (Preston delicately refers to this as the Left resisting “electoral disunity”).

By 1934, though, this became untenable, so some minor ministerial offices were granted the CEDA. The response of the harder left side of the Republicans, led by the Socialists, was to launch a widespread revolt (often today euphemistically called a “general strike,” but called at the time by the Socialists a “revolutionary strike,” with the avowed aim of “overthrowing the government and taking power”), passively supported by the rest of the Republican parties.

Only in the Asturias mining regions did this succeed, for a time, with the Republican revolutionaries killing around a hundred of their local political opponents out of hand, burning churches and stealing millions from local banks.

The revolting miners, as Hugh Thomas points out, were very well paid; “[t]heir action was politically, rather than economically, inspired.” The Asturias rebellion was put down by Franco, using Moroccan troops; Payne says “the army units also committed atrocities, and there may have been as many as a hundred summary executions, though only one victim was ever identified, despite the vociferous leftist propaganda campaign that followed for months and years.”

It is worth spending some more time on the Asturias rebellion, for a few reasons. For one, it was the first time Franco came to be seen as an enemy of the Left, and his successful defeat of the Left meant that he became a permanent target of the Left’s hatred.

The Asturias rebellion is also an example of the propaganda machine of the Left, which for nearly a century has used this as the supposed inception of the Civil War, conveniently ignoring not only that it was a Left revolt to overthrow an already leftist government, for the sin of allowing a center-right party to participate in the government at all, and that violence had been a stock tactic of the Spanish Left, by 1934, for several years.

Finally, and related to the second reason, the Asturias rebellion is a good way to gauge how susceptible an author is, himself, to propaganda; it is a standard candle.

Payne, as I say, offers specifics—maybe a hundred dead leftists in summary executions—but he offers a footnote, “Within only a few months leftist spokesmen were permitted to present charges of atrocities before a military tribunal. The resulting inquiry produced concrete evidence of only one killing, though probably there were more. The most extensive study on this point is [a 2006 Spanish-language monograph].”

Hugh Thomas gives the figure as about 200 killed “in the repression,” though he offers no support for his figure. Overtly Left mouthpieces commonly talk of “thousands” killed. Preston offers no figures, he merely complains for pages about “savagery,” “brutality,” “howling for vengeance” and such like, while making racist statements about Franco’s Moroccan troops.

This pattern continues in almost all high-profile events in the Civil War—all of which are high profile because they were specifically chosen by the Left at the time as the most susceptible to use for their global propaganda campaign.

This was all run-up to the fatal elections of February, 1936, in which the CEDA contested against a “Popular Front” of rigidly leftist parties. The election was called by the President, Alcalá-Zamora, specifically to prevent the CEDA leader, José María Gil-Robles, from becoming Prime Minister.

The result was probably an extremely narrow victory for the Popular Front, marred by extensive pre-election violence (almost exclusively by the Left, as Payne notes) and leftist mobs in numerous areas “intefer[ing] with either the balloting or the registration of votes, augmenting the leftist tally or invalidating rightist pluralities or majorities.”

Rather than wait for the normal processes for handover of power, the Left immediately seized power wherever it had the ability, releasing their compatriots from jail, and illegally and forcibly “unilaterally register[ing] its own victory at the polls.”

The Left’s behavior with respect to the CEDA is similar to the electoral behavior of the American Left today. It is not quite as dramatic here, because in the American structure the tools are lacking to actually deny power to a party that wins seats.

The American system is more cut-and-dried in that way. Therefore, when conservatives threaten to gain any actual power, other actions are instead taken. The first line of defense is to allow neutered conservatives “in the government,” like John McCain or Mitt Romney, on the condition they never, ever, attempt to actually deny any victory to the Left.

The second line of defense, against those who are not, like McCain and Romney, quislings deep in their souls, is to use the press, dominated by the Left and able to wholly determine what is considered news, to open propaganda campaigns to delegitimize conservatives who threaten to actually exercise power.

The third line of defense is legal attacks by either civil suits or the organs of the state. And the fourth line of defense, the trump card (no pun intended) is to use the courts, in particular but not limited to the Supreme Court, to simply, much as in the old Spanish Republican way, to illegally deny the exercise of power to conservatives.

This last strategy is wholly successful in only a few areas, related to claimed emancipatory autonomy (notably abortion and sexual license), because the Left does not control every aspect of the Supreme Court as it so dearly desires.

The Left’s response to not being able to completely control the Supreme Court has been, when this fourth level of tactic is needed, to drag every conservative attempt to exercise power through legal molasses, by suborning low-level federal judges into issuing ludicrous and unlawful decisions based purely on the desire to advance Left goals, and imposing nationwide injunctions mandating the desired result.

After many months or years, if the Supreme Court has time to add such a case to its docket, the lawless decision is reversed, with no consequence or sanction to the original judge (quite the contrary), but the Left goal has usually been mostly or totally accomplished.

This system is intolerable—conservatives should find a good issue and declare a refusal to adhere to such an injunction, and such lawless judges should be severely punished. But that is a discussion for some other time.

Back to February, 1936. Whether the election was truly won by the Left is unclear. Hugh Thomas thinks it was, though by a slim margin. Payne is less sure, and emphasizes that vote totals can’t tell the whole story when votes were suppressed by leftist violence and fraud.

Payne notes that “There were runoff elections in several provinces in March, but in the face of mounting violence the right withdrew, adding more seats to the leftist majority. Late in March, when the new parliamentary electoral commission convened, the leftist majority arbitrarily reassigned thirty-two seats from the right to the left, augmenting that majority further.”

Elections in conservative provinces were declared invalid; and in the re-runs, conservatives were violently prevented from running.

Payne’s conclusion is that “In a four-step process, electoral results originally almost evenly divided between left and right were rigged and manipulated over a period of three months until the Popular Front commanded a majority of two-thirds of the seats, which would soon give it the power to amend the constitution as it pleased. In the process, democratic elections ceased to exist.”

But both Payne and Thomas agree that after the initial vote, the Left manipulated the system to try to expand a dubious majority. The details of this episode are glossed over by Moradiellos, who prefers to simply claim that the Popular Front won a “slight” victory and move on, and simply ignored by Preston, who says the victory was “narrow” but resulted in “a massive triumph in terms of seats in the Cortes,” without any explanation of how that could be.

(It is about here in reading Preston’s book that one realizes that his normal tactic is to lie by omission, while burying the reader in mounds of irrelevant detail, making his account seem complete.) At the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter, since the Left’s goal was the permanent seizure of power, and this was the handy trigger. If it hadn’t been this, some other pretext would have been used to violently cement power and permanently, or so they thought, destroy the Right.

The Republicans immediately unleashed a nationwide assault against the Right. Payne asks, “How bad was the situation by July 1936? The frequent overt violations of the law, assaults on property, and political violence were without precedent for a modern European country not undergoing total revolution.”

These included looting, arson, massive theft, “virtual impunity for criminal action by members of Popular Front parties, manipulation and politicization of justice, . . . and a substantial growth in political violence, resulting in more than three hundred deaths.”

The military began to actively plot overthrow of the government, though Franco was not initially actively involved and hedged his bets (his calculating, and some thought cold, manner of approaching such decisions was not pleasing to his Army compatriots).

But on the night of July 12, 1936, José Calvo Sotelo, the charismatic chief Monarchist in parliament, was brazenly assassinated by the government’s Assault Guards (indirectly assisted by the Republican Minister of the Interior), in revenge for the murder of an Assault Guard prominent in anti-Right violence, José Castillo, by the Falange, the small Spanish fascist party.

The Republican government’s reaction was to arrest nobody but two hundred rightists and to continue its campaign of repression. (Preston characterizes this as “immediately beginning a thorough investigation” and then does not return to the matter).

For many or most on the Left, most prominently the Socialist leader Largo Caballero, a military revolt was desired, since they believed the Republicans could crush it and thereby permanently seize power without further pushback.

And regardless of desirability, most on the Left now believed in the “necessity” of civil war. “Thus, in the final days neither the government nor the leftist parties did anything to avoid the conflict, but, in a perverse way, welcomed military revolt, which they mistakenly thought would clear the air.” (Their mistake, actually, was not that it did not clear the air, but that the fresh air was not to their liking).

Logically enough, Payne pegs this as the point at which the generals, and Franco, realized that it was more dangerous not to revolt than to revolt, so the war was on. The generals (not yet under Franco’s leadership) launched their revolt; the government handed out weapons to the Left. And the war came.

The Civil War

All Franco biographers cover the war in detail. It lasted three years. Soon Franco was granted supreme military and political control by the other counter-revolutionary generals, in part because he had the best troops, in part because he managed to be the conduit for equipment from Mussolini, and in part because of his dominant personality and the near-universal admiration in which he was held among the military.

The Republicans held several of the major cities; the Nationalists others and the countryside, where they had broad-based support, especially among poor peasants. The Nationalists, in the areas they controlled, deliberately implemented a counter-revolution to end leftist and liberal domination; they “embraced a cultural and spiritual neotraditionalism without precedent in recent European history.”

In their political theory, following Joseph de Maistre, arch-opponent of the French Revolution, a counter-revolution was not the opposite of a revolution, which would make it Burkean, but an opposing revolution. The Spanish Civil War showed that Burkeanism has very definite limits, after all; appeals by American conservatives to him and to Russell Kirk, past a certain point in the polity, which we have not reached yet, are only of any relevance or use once the smoke clears and the bodies are buried, and serve before then only to hamstring conservatives in their reaction to those who would destroy them.

Despite their far superior organization (though the Republicans improved theirs over time), the Nationalists were inferior to the Republicans in domestic propaganda, and far inferior in international propaganda. In part this was because the people in charge on the Nationalist side were military men, both disinterested in and contemptuous of propaganda.

Their idea of propaganda was to broadcast choleric and threatening radio addresses into towns they were attacking. In part it was because the Left has always been master of propaganda, a fact on display both inside Spain, where morale was kept up by inspirational posters and mass rallies (though the Nationalists used posters too), and even more so outside of Spain, where the international Left eagerly created a distorted perception of the Nationalists and the war.

The Falange, the Spanish fascists, are rarely a significant focus of discussions about the Civil War, except in propagandistic discussions. This is because they were not notably powerful; they were merely one part of the mix of Nationalist politics, which included many military men not aligned with a party, monarchists (in two brands), and Catholics (who opposed the Falange generally, and violently opposed modernist foreign right-wing political movements, especially National Socialism).

The Falange, in any case, lost most of their independent power when Franco forcibly took over the party as the vehicle for his “National Movement,” cramming, in theory, everyone into his personal party and blurring the lines between himself and the Falange. During the war and immediately after, Franco identified himself publicly with the Falange.

He was happy to accept their support, and encourage the cult of their leader, executed early in the war by the Republicans, José Antonio Primo de Rivera (son of the dictator)—as many have pointed out, it was convenient for Franco to only have to compete with a dead man. After the war, with his typical cold calculation, Franco suppressed what power the Falangists still retained, seeing them as adding no value to his neotraditionalist Movement, and being far too interested in radical modernism.

Nobody who is serious contends that Franco was fascist in any meaningful way—that is, under any actual definition of fascism, rather than under its use as a flexible term of abuse. (Moradiellos offers a detailed analysis of the use of the term in modern Spanish scholarship.) Nomenclature can be misleading if transposed without thought into today.

To take another example, Franco regularly used the term “totalitarian” as a positive, something inconceivable to us after seeing the results of totalitarian regimes in the twentieth century.

But when Franco described the Movement as totalitarian, he meant not that it would attempt to control every aspect of life, even people’s thoughts, which is the meaning we imbibe from Communism and from works like Orwell’s 1984. Nor did he mean that politics would continuously invade and dominate all areas of life; Mussolini’s famous definition of fascism as “Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state.” Rather, he meant a system “that would dominate the public sphere but otherwise permit a limited traditional semi-pluralism.”

By way of example Franco offered fifteenth-century Catholic monarchs. Moreover, the Movement was meant explicitly to advance a flexible plan, not a program. “It will not be rigid or static, but subject, in every case, to the work of revision and improvement that reality may counsel.” Franco looked backward, not forward to ideological rightism.

The same distorted nomenclature is true of “dictator,” originally a Roman term used not as a term of opprobrium, but of description, and until the modern era, seen as simply another possible method of political organization, useful in certain circumstances but, like all political organization, subject to abuse.

In fact, as Moradiellos discusses in some detail, around this time the concept of dictator received the attention of Carl Schmitt, who distinguished between the commissarial and sovereign forms of dictatorship, in particular as they related to early twentieth-century Germany. In this taxonomy,

Franco was a sovereign dictator—but that does not imply that his rule was arbitrary or despotic, the meaning we typically take from the modern use of the term. Franco had very definite and very simple core principles. But beyond those, he was politically flexible—not, for example, wedded to a monarchy after his death, and when he decided that was the best course, not quick to decide which monarchical line should ascend the throne (left vacant after 1931). And Spain under Franco was very much a country of the rule of law.

There is no need here to rehash the details of the war. In short, Franco gradually rolled up the Republicans, after trying and failing to quickly capture Madrid and end the war. It is fairly evident that Franco did not mind a longer war; as Moradiellos emphasizes, this enabled him to permanently repress the Left by killing his opponents and scaring the rest into final submission (shades of Sherman’s March to the Sea). Both the Axis and Stalin supplied the Nationalists and Republicans respectively, but that almost certainly did not change the end result of the war. By 1939, it was over.

Immediately upon the beginning of the Civil War, both sides began systematic executions of their political opponents in areas they controlled. Contrary to myth, this was organized on both sides, though as with all things better organized by the Nationalists.

It was not some kind of excusable spontaneous excess on the part of the Left, as they have often tried to pretend during and since, the line that Preston uniformly takes as well. Other than being factually wrong, such a claim is laughable on its face when viewed hindsight from the twenty-first century, since in, without exception, every other Left accession to power, organized mass killing of opponents in order to create the “new world” has been an absolutely essential and central part of the plan, invariably carried through if and to the extent power is gained.

As with many other Left actions and claims, from denying the evil of Lenin to the guilt of Alger Hiss to who was responsible for Katyn, they may have been plausible once, but current belief brands one as either a liar or a fool. In fact, such violence had openly been part of the Left’s plan in Spain for years.

True, on both sides the organization of killing outside of battle was mostly locally organized, not centrally organized. Payne says “It is now generally agreed that the number of executions by the [Republicans] totaled about fifty-five thousand, while those by the Nationalists were more numerous, with estimates ranging from sixty thousand to one hundred thousand or more.

The higher figures appear to be a demographic impossibility, so that the low estimate appears more likely. In the long run, the Nationalist repression became more concerted, was the more effective of the two, and claimed the most lives, particularly with the extensive round of executions after the end of the Civil War.” Preston agrees with these numbers, though his estimate is on the higher end, which suggests, at least, rough agreement across the historical spectrum.

Of course, this is comparing apples to oranges, because it ignores two critical elements. First, the Left killed fewer because since they conquered little territory, killings were mostly confined to the cities they held when the war began, and therefore could not accomplish their goal of wiping out all those on the Right, merely those unfortunate enough to be trapped with the Republicans (including a high percentage of the country’s Army officers). (And, as famously narrated by Orwell in Homage to Catalonia, soon enough the Communists turned to stamping out former allies on the Left).

Second, it ignores the certainty that the Republicans would, like all Communists coming to power, have slaughtered enormous numbers of people after the war for many years, so including post-war executions in a comparison is a distortion.

It would be far more realistic to assume that the Republicans would have executed some double-digit multiple of those the Nationalists executed; it would have been like the Jacobins in the Vendée. And, critically, unlike Left regimes, which are always focused on killing by class and status in order to achieve utopia, not the punishment of specific crimes, Franco’s repression quickly became less radical, not more radical.

As Payne notes, “Once the major actors and criminals of the Spanish revolution had been prosecuted, there was no need to repeat the process.” That would not have been true if the Republicans had won.

Thus, such killings by the Nationalists during the war had nothing in common with the ideological killings of the twentieth century, whether by Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Pol Pot, or many others. Rather, they were conducted under a semblance (sometimes dubious or even specious) of the rule of law, through military tribunals, directed either at those known to have committed significant crimes (as the Republicans had in every area they controlled) or, a smaller number, those who were leaders of the revolutionary opposition.

I find the latter hard to morally justify, sitting comfortably in my twenty-first-century seat of luxury and security, but in context, I do not find them hard to understand (and I understand the Republicans’ killing of political opponents as well); nor do I find the “victims” in any way blameless (although there must have been mistakes and excessive severity in many cases, as is always the case in wartime situations).

Regardless, this was not the type of class- or race-based killing common in the twentieth century, sweeping up without specific accusations and guilt men, women, and children. It was political and executive judgment on actual enemies working to destroy their countrymen, and that’s what happens in civil wars.

Preston, in 2012’s The Spanish Holocaust, addresses killings during the war. But unlike his magnum opus, his biography of Franco, this later book is a work of unhinged propaganda, designed to whitewash and excuse all Republican killing, and to magnify the horror of all Nationalist killing. Words such as “savage” and “vicious” appear with metronomic regularity, never once applied to Republicans.

The default mode is the passive voice when, infrequently, Republican killings are described, always in the context of excusing them. Preston makes truly ludicrous claims, such as that during the entire Civil War, there took place (he cannot bring himself to use the word “rape” by Republicans) “the sexual molestation of around one dozen nuns and the deaths of 296,” a low toll he attributes to the “respect for women that was built into the Republic’s reforming programme.”

Naturally, he does not mention the roughly 7,000 other clergy executed by the Republicans, except obliquely, without numbers, and to excuse them as unfortunate, but understandable, excesses by zealous heroes. On the other hand, as I say Preston uses the same numbers of dead as Payne and other unbiased scholars; his fault is in propagandistic presentation and the use of anecdotes that are mostly almost certainly lies, not statistics (in fact, Payne uses higher numbers for those executed after the war, 30,000 instead of Preston’s 20,000).

There is not much more to say about this book, but if you’re interested, you might try reading Payne’s bloodless evisceration of it in a Wall Street Journal review. “Mr. Preston, rather than presenting a fully objective historical analysis or interpretation of violence against civilians during the Spanish conflict, is recapitulating civil-war-era propaganda. . . . Rather than implementing some radical new Hitlerian or Pol Pot-like scheme, the essentially traditionalist Franco followed the policy of victors in civil wars throughout most of history: slaughtering the leaders and main activists of the other side while permitting the great bulk of the rank and file to go free.”

Franco did not care what it took to put the Republican revolution down. Such was Franco’s personality—practical, tending toward icy, in his political relations. Really, though, Franco’s personality was somewhat opaque; he kept no journal and what few personal papers he had are still mostly in the possession of his family and not public.

He was, in both personal and military matters, straightforward for the most part. He took counsel from others, but was decisive when the time came to make a decision. Most importantly, he shared two crucial characteristics with me. He fell asleep immediately upon going to bed, annoying his wife because she wanted to talk, and he hated rice pudding. Beyond that, though, it is hard to say in many cases what Franco thought.

No surprise, however, at some point Franco, at least to some extent, began to believe his own press. He did not become puffed up, much less behave badly—he was always punctilious in his personal behavior, and did not fly into rages or otherwise show lack of self-control like many dictators.

But he did become convinced that he was an instrument of Providence, always a dangerous belief. He also prided himself on some minor abilities he did not have—for example, he believed he was an expert in economics, whereas everyone knew he was not. Regardless, Franco developed a charismatic form of leadership, and was never challenged for leadership. Payne’s conclusion is that “the effort to achieve legitimacy [was] thus more praetorian or Bonapartist than Fascist.” That seems about right.

In any mention of the Civil War, another standard candle, the 1937 bombing of the Basque town of Guernica by the German Condor Legion, always comes up. This is not because it was the only, or the most damaging, aerial bombing of the war, but because the Left chose it as the focus of a propaganda campaign. Aerial bombing was then highly inaccurate (my grandmother’s house in Debrecen, Hungary, during World War II, was partially destroyed as the result of American bombs missing the railway station).

Payne notes that far from the “planned terror-bombing” of leftist fever dreams, the bombing of Guernica was a routine strike on a military target (and as Payne notes, “indiscriminate attacks on cities, almost always small in scope, were in fact more commonly conducted by the Republican air force,” giving the example of the bombing of Cabra, which killed more than a hundred civilians, but of which you have never heard).

Preston, of course, ignores these facts, and accepts at face value high-end, propagandistic claims for the number of dead. The inept and mendacious Nationalist response, including the suggestion that the Republicans had burned Guernica themselves to deny it to the Nationalists (it was a largely wooden town), made things worse for the Nationalists. But it was propaganda gold for the Left, who inflated the casualty figure, Payne says, “approximately one thousand percent” (the real figure was around 200, maybe somewhat more or less, and only that high because an air-raid shelter took a direct hit).

How many Spaniards died in the war? All in, maybe 350,000 by violence, including battle deaths, executions, and civilian deaths, with maybe 200,000 or 300,000 more due to “extremely harsh economic and social conditions.”

But, as Payne says, “[I]t would be hard to exaggerate the extent of the accompanying trauma the war inflicted on Spanish society as a whole. The complete destruction of the normal polity, the ubiquity of internecine violence, and the enormous privation and suffering left many of its members shell shocked and psychologically adrift.”

This in part explains why Franco faced nearly zero domestic opposition during his lifetime—nobody wanted to go back to that. They were reminded of that by a low-level terroristic Communist insurgency in the late 1940s, which killed several hundred people, mostly in train and train station bombings (and which Preston characterizes as heroic resistance).

After The War

After the war, Franco and the Nationalists cemented their power. As Payne says, “Franco planned not merely to complete construction of a new authoritarian system but also to effect a broad cultural counterrevolution that would make another civil war impossible, and that meant severe repression of the left.”

Forceful action to that end was characteristic of the immediate post-war period, with nearly 300,000 imprisoned in 1939, though most were released in 1940. “The Francoist repression, despite its severity, was not a Stalinist-Hitlerian type of liquidation applied automatically by abstract criteria equivalent to class or ethnicity. The great majority of leftist militants were never arrested, nor even questioned.”

The death sentence was reserved for political crimes involving major violence. Still, there were many executions after the war, much along the same lines as during the war, but with more due process, and quite a few jail sentences—though unlike today in America, when multi-decade sentences for relatively minor crimes are the norm, the sentences were relatively short and soon enough even those convicted of being involved in political killings were released from jail, certainly by the late 1940s.

Preston does not talk much about postwar justice in his biography of Franco, moving quickly to World War II and contenting himself with occasional references to “savage repression,” without much more detail, which superficial treatment by omission reinforces Payne’s more detailed account.

Franco’s goal in 1939, and onward, was to not only complete the conservative counter-revolution and create neotraditionalism on a social level, but to economically modernize the country and make Spain relevant on the world stage. He saw no contradiction between those two things, a failure of prediction, though understandable through a backward-looking prism. In other words, Franco wanted to make Spain great again, by which he meant forgetting the entire previous 150 years.

By economic modernity, Franco meant mostly autarchy, not development relying on foreign trade or foreign investment. And by global relevancy, Franco meant an authoritarian regime with an international presence, mostly at the expense of the French in North Africa. Retrospectively, both these goals seem half-baked.

But from the perspective of the time, both autarchy and authoritarian regimes, of left or right, were the coming thing in Europe, so Franco was not swimming against the tide. In fact, as with many people across the globe, including in the United States, Franco believed firmly that, globally, “the democratic system is today on the road to collapse.” He was wrong, although perhaps his prediction was premature, not wrong.

Still, Franco claimed to be democratic. What that meant was what he, and the Spanish political scholars of the time, rejected “inorganic democracy,” consisting of pure majority rule. Instead, he wanted “organic democracy,” where voting was organized around groups (e.g., family voting; syndicalism); local institutions (including, but not limited to, the Church) had significant power (in essence, subsidiarity); and, naturally, a strong executive power, in the form of himself (as “caudillo”) or, later, a return to monarchy.

As Moradiellos cites the Spanish legal theorist Luis del Valle Pascual, it was “based on the basic social forms (corporations, families, classical municipalities) and formulated by a ‘command hierarchy’ according to a ‘fair principle of selection.’ ”

If the Nationalists had won quickly, as was widely expected, nothing would have been settled. The irony is that the Civil War sought by the Left to permanently destroy the Right ended up doing the opposite. Both because of the smashing of the Left during and after the war, and because the great mass of Spaniards never wanted to return to the dark days of the war, Franco was able to remake Spain after the power of the Left was permanently broken.

True, Spain was ruined after he died, but not in the way that would have resulted if the Nationalists had not launched their counter-revolution, by mass slaughter and establishment of a Communist utopia. Those elements of the Left, as in Greece, were destroyed, and most of their successors took a different, Gramscian tack, resulting in Spain taking the same path to decay as the rest of Western Europe.

Franco’s governmental system therefore involved an “indirect and corporatist scheme of representation.” Whatever the specifics, which changed somewhat over the decades, the regime was widely supported by most of Spanish society (although foreigners could be forgiven for not realizing that, given the ongoing global Left propaganda campaign).

Nobody wanted to go back to the war, and most people, with the usual exceptions of some urban workers and radicalized agricultural laborers (along with Catalan and Basque separatists), saw that the Republicans having won would have been very bad indeed.

The majority of the revolutionary/Republican leaders had been executed or fled the country, and the rest of the remaining Republicans kept their mouths shut (although they were not persecuted). Franco emphasized the country’s Catholic identity, and he used the Movement to keep a firm lid on all segments of Nationalist support, gradually downgrading the Falange and keeping a firm lid on the monarchists.

From 1939 to 1945, Franco tried to get as much benefit as he could from the Second World War without becoming directly involved. Spain couldn’t actually join the Axis without imploding, since it depended on British-supplied oil and was in dire economic straits.

But Franco wanted to expand Spain’s possessions in North Africa, and when Hitler and Mussolini were at the height of their power, he was only too happy to curry favor—while refusing to actually offer anything meaningful, trying to keep up his balancing act of not overly angering the Allies. Certainly, Franco resonated with some aspects of National Socialism and Fascism, but was never interested in such systems being imposed in Spain, and refused to participate in persecutions of the Jews, accepting thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing France and ignoring the protests of the Germans and the Vichy French.

The major contribution to the Axis was that thousands of volunteer Spaniards fought against the Soviet Union, in the Blue Legion. Soon enough Franco realized that Hitler had reached his apogee, and delicately sidestepped away, trying to pretend that he was never really that serious about it anyway, and don’t you know that Communism is the real enemy? Still, this is probably the least attractive period of Franco’s career, though I suppose people who allied with Stalin shouldn’t really find too much fault with Franco’s choice of wartime friends.

Thus, Franco would have gotten autarchy even if that hadn’t been an economic goal of his, because after 1945, Spain was wholly isolated, due to its association with the Axis, and due even more to the global hatred of the Left for Franco and his success against the Left. Such rage dominated the American perspective, as well as pretty much every other major country other than England (where Churchill was very open that were he Spanish, he would have been a Nationalist).

Soon enough, though, between hard diplomatic work and the aggression of Stalin, relations with the United States improved. Under Eisenhower they became positively warm. Therefore, with his usual luck, Franco managed to emerge from World War II with Spain in a reasonably good position, and without the recurrence of the Republican threat.

Still, the 1940s mostly consisted of Spain staggering along economically. Moreover, this, along with Franco’s excessively relaxed attitude, encouraged widespread corruption, always the hallmark of a system with troubles (although Franco himself did not build a fortune, nor did his family get especially rich, at least by the standards of most authoritarian regimes).

Postwar Spain very much had the rule of law. Franco never interfered in the judicial process, which was uniformly applied (even though technically supreme judicial power was vested in him). The Cortes had free discussion. Every so often there were still death sentences, such as that imposed on Julián Grimau in 1963. Grimau was a Republican police officer who had been in charge of an infamous Barcelona prison where many were executed (mostly leftists in disfavor, but some Nationalists too).

He returned to Spain (why is not clear) and was arrested and sentenced (somewhat dubiously, using an obscure statute to get around the expiration of the statute of limitations).

This incident would not be important except for what it says about the Left and its lies. “The Communist leader was painted in the international media, however, as an innocent oppositionist, a peaceful organizer, about to be executed exclusively for being a political opponent. A massive clemency campaign got under way. . . . The Spanish embassy in Paris was firebombed.”

Nonetheless, Grimau was executed, causing more howls of rage from the Left, which succeeded in imposing another short period of international ostracism. Why this matters is that it shows that any claim made by the Left, that is, any claim in mainstream currency that makes the Nationalists look bad, has to be examined not only for its tilt, but for whether it has any truth at all, or is simply a pack of lies. Since the Left is so often able to control the narrative, and never has to pay any price for lying, it is encouraged to lie.

Franco maintained political order, and dropped his demand for autarchy, not so much because he had changed his mind but because he was convinced of the need to do so by his technocratic advisors (most of them Opus Dei members, including Franco’s closest advisor for decades, Luis Carrero Blanco, assassinated by a Basque bomb in 1973).

The idea that Franco ruled “with an iron hand” is silly; he actually didn’t spend much time ruling at all, and most governing was done by his cabinet, which he carefully balanced among competing political interests and periodically reshuffled to that end. “Franco was a ‘regenerationist’ who sought to economically develop his country while restoring and maintaining a conservative cultural framework, contradictory though those objectives were.”

Political controls, whether over the press or the political activity of unions or individuals, loosened over time, which was criticized by the Right and taken as a sign of weakness by the Left. That said, the political controls were never very aggressive; Solzhenitsyn was widely criticized by the Left when he visited Spain after he was exiled by the Soviets and snickered at the Spanish Left’s claim that they suffered under Franco; he pointed out that they could buy all the foreign newspapers they wanted, move wherever they wanted, and only suffered the lightest censorship. He was not invited back.

“The last twenty-five years of the Franco regime, from 1950 to 1975, was the time of the greatest sustained economic development and general improvement in living standards in all Spanish history.” GDP rose an average of 7.8 percent per year through the 1950s.

Payne compares Spanish economic policy in the 1960s to that of China today, noting that “the two main differences are that there was greater freedom in Spain during the 1960s than there [is] in China and that the proportion of state capitalism was much less.”

But, as Payne also notes, “Modernization resulted in a profound social, cultural, and economic transformation that tended to subvert the basic institutions of Franco and his regime.” The birth rate was deliberately, and successfully, encouraged to stay high. Land reform was gradually introduced, as was universal education.

All in all, Spain was made great again, although no doubt the carping Left managed to convey a different picture to the world of the time. But as this happened, in the 1960s and 1970s, Franco became somewhat out of touch, and more out of sympathy, with the new booming, glitzy, consumerist Spain, even if that was the inevitable result, at least in that era, of the economic dynamism he had sought and achieved.

Franco died in his bed in 1975, slowly and painfully but with no complaint, with his rule never having been challenged, and having carefully arranged the succession of political power to a restored monarchy, in the person of King Juan Carlos, grandson of Alfonso XIII, deposed in 1931. What Franco wanted was a strong monarchy, an avoidance of a return to political parties, which had caused so much trouble in the early twentieth century, and continued neotraditionalism.

He got none of those things. All the things that Franco had tried to do, except to prevent a Communist takeover, were largely and swiftly overturned, many even before he died. Materialism and consumerism ruled Spain; the birth rate plummeted; even the Church, long a bulwark of Francoism, turned left, with younger priests engaging in subversive activities and even encouraging violence (a harbinger of the corruption that has now swept over the Roman church).

King Juan Carlos, although he was more liberal than Franco hoped, but probably no more liberal than Franco thought likely, ensured that the Left was not able to immediately retaliate against Franco supporters as they gained power. So for some years Francoism was mostly ignored. Some writers, including Moradiellos, contort themselves to derive meaning from this silence.

They attribute it to a tacit agreement to move on. But silence is the default for all the great leftist crimes of the twentieth century; this attempt to derive meaning is merely an expression of surprise at the Left’s inability to successfully persecute anyone associated with Franco and Francoism after the end of that political system.

More likely this silence is indifference by modern Spaniards, who refused then and still refuse today to endorse the Left’s usual campaign to silence and punish their opponents of decades before.

Political memory is the essential fuel of the leftist engine of destruction, which requires delegitimizing any regime opposed to the Left, and that, as Moradiellos complains, a third of Spaniards choose “none” as their “personal political attitude to the immediate collective past,” simply shows that, for whatever reason, Spaniards generally refuse to buy into the Left’s hysterical demands for rewriting the past and using it for oppression in the present, which is to their credit.

In recent years the silence has been broken, because the Left in Spain has been running an aggressive campaign against Francoism, since the Left never forgets, unlike the Right. A key component of these campaigns is always the elimination of any agreed-upon amnesty that was offered the Right (the Left has a permanent amnesty in all cases, whether or not the law says so).

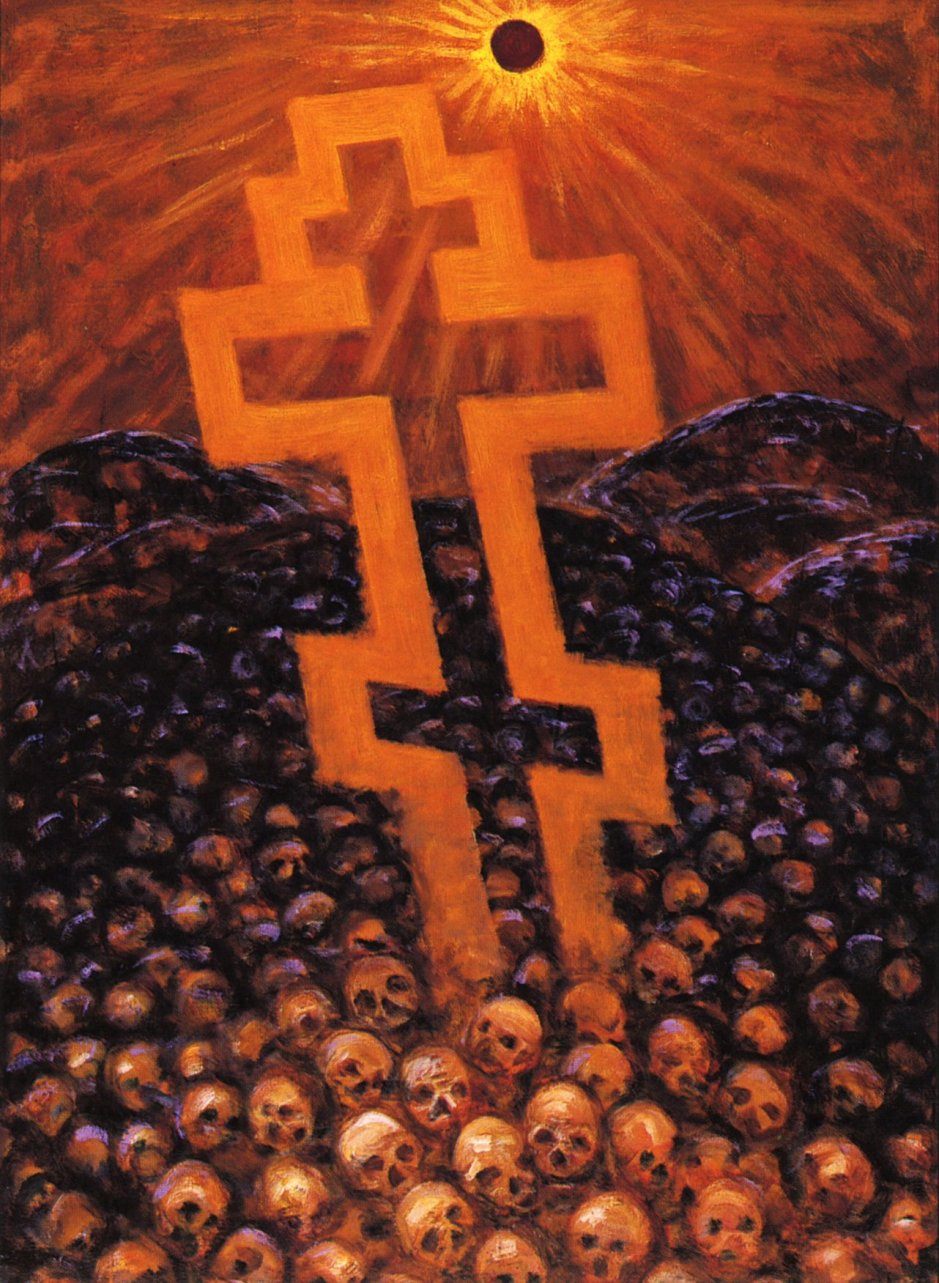

This campaign gets occasional notice in English-language media. One element of this has been to attack the mausoleum for Civil War dead Franco erected at the Valley of the Fallen (where he is also buried, although he did not specify that wish). The claim is made that it was built by “slaves”; Peter Hitchens echoes this claim.

Payne disagrees, and as always offers specifics as opposed to the generalities of leftist propagandists. “Such accusations are exaggerated. Between 1943 and 1950 a little more than two thousand prisoners convicted by military courts were employed, but they received both modest wages, as well as fringe benefits for their families, and a steep reduction in their prison terms, ranging from two to six days of credit for each day worked. Each was a volunteer for the project, and there were rarely more than three to four hundred at any given time. They worked under the same conditions as the regular laborers, and some of them later returned to join the regular work crew after completing their sentences.” The Pyramids this was not.

And a few weeks ago the Spanish government announced that Franco’s body would be disinterred. At least they are reinterring him in a government cemetery, rather than throwing his body in the river, though wait a few decades, and maybe that will happen too.

What Does This Imply?

We have now reached the point where, inevitably, I try to derive lessons for today. As always, one should not try to shoehorn the present into the past. Much is different between 2019 America and 1936 Spain, and not just that people are a lot fatter now.

The specific political issues of the day are quite different, in part because everyone being wealthy by historical standards long ago destroyed the mass appeal of Communism and true socialism (even if it appears to be having a resurgence of sorts), and anarchism is not on any relevant menus. Such specifics are less important than the basic divide between Left and Right, however, which remains exactly the same as it was in 1936.

The atrociously low level of public discourse today also adds to confusion; it is difficult sometimes to grasp the nub of arguments with the tremendous amount of chaff flying around in the air. But beyond these, there are two differences that really matter.

First, the divisions are much more poorly demarcated in America today. In Spain, who was Right and who was Left was clearly evident to everyone. Today, who is Left is mostly evident, though somewhat vaguer than in Spain, with more spread-out power centers and leadership, as well as more fragmented issues of focus.

But there is no equivalent in America today to any part of the 1930s Spanish Right. There is no powerful, organized opposition, or any organized opposition whatsoever, to the Left. The closest thing to an opposition is the masses of “deplorables,” who are denied all power by both the Democrats and Republicans in America, the latter group existing mostly to provide a pseudo-opposition to the Left, by promising the deplorables what they want and then reneging on even trying. No equivalent exists to the monarchists, or the Falange.

There is no powerful media that advances the Right agenda; there are some outposts of conservative monologues, and some Internet stars, but they are not allowed to set the narrative, which is wholly within the grasp of the Left or its enablers, as are the universities, the schools, all big corporations, and the entertainment media. Intellectual groups of conservatives in America are ineffectual, with no actual power or influence and no path to achieve it (although some could offer intellectual heft if there were an actual Right).

Second, and a consequence of the first difference, the specific enemies of today’s American Left are less clear. Spain had Right institutions staffed by people who could be easily targeted: the Church, the Army, the right-wing press, right-wing academics.

The Left focused on winning by eliminating those people. Today’s Left could not do that; if the Left were going to conduct a campaign of violent suppression, the targets would merely be occasional individuals who form the beginnings of a threat to the absolute Left hegemony (e.g., Jordan Peterson), not Right institutions or classes of people staffing those institutions, since there are neither such institutions nor such classes of people.

True, today’s Left does not need to do that, since it has gathered all power to itself, but either way, it makes attacks such as the Left conducted in Spain mostly pointless.

These two differences imply that a civil war here, today, of the type fought in Spain is very unlikely, whatever dark mutterings about the possibility keep cropping up on both the Right and Left. Even if the Right wanted to start a violent counter-revolution, it is not even remotely clear how that could be organized, or what the practical goals would be.

And the flashpoints that actually started the Civil War, private killings sanctioned by the government, are, despite the prevalence of low-level violence by the Left, really totally absent in America today. One can predict that they’re coming, but there’s little actual evidence of that, even if the normal historical arc of the Left is to converge on the desirability of physically eliminating opposition.

Sure, there is plenty of evidence of soft totalitarianism, where the Right is actively suppressed by denying prestigious education and remunerative employment, as well as membership in the ruling class, to anyone who dares to challenge the Left. It’s very hard to organize, or justify, high-level violence as a response to that, though. So yes, someday the grasp of the Left may exceed its reach, and result in civil war, but that does not appear imminent.

Such optimism, however, if that is what it is, depends on wealth, which can paper over a lot of sins and structural problems. The Left in power inevitably destroys wealth, because it always wants to enforce equality, by taking from the haves and giving to the have nots (hence the resurgence of true socialism).

The neoliberals who are only hard Left on social matters, while maintaining some semblance of economic reality (at the same time oppressing actual workers), will likely give way to the more attractive religious beliefs of the Marxists, while even on social matters they eat their own—both processes we see beginning in the current Democratic race for President.

At root, the Leftist program always has as its ultimate aim the achievement of utopia through the accomplishment of two concrete goals—remaking of society for “equality,” and the destruction of all core structures of society and their replacement by celebration of various forms of vice, this latter process labeled “liberty.”

It appears that people will, if it’s done non-violently, tolerate the former so long as their cup of consumer goods is full. When the music stops because the money runs out, whether because of economic irrationality or some externally imposed rupture, all bets about civil war are going to be off, because, I predict, the demarcations, and the leadership of groups so demarcated, will immediately arise.

The problem is that such demarcation will likely result in civil war, unless reality defeats and discredits the Left first, which is certainly possible. If not, it will have to be defeated permanently, as Franco very nearly did. It does no good to put the Left down if they will simply rise again; it is pointless to play Whack-A-Mole.

The Left must be stripped of all power and fully discredited, and to be discredited, it must be viewed by future generations as the intellectual equivalent of a combination of Nazism and the worship of Sol Invictus. I am not sure if that is even possible, since what the Left offers is so very, very seductive.

At a minimum it would require in the present day the equivalent of denazification; or perhaps the same kind of successful forgetting of the past implemented by King Charles II after the Restoration (not the typical Left forgetting of the past, which is just biding time until their past enemies can be destroyed). But it would also require offering something attractive as an alternative to the Leftist poison dream, which Franco did not do—he offered the past, which while better, does not inspire, and cannot be returned to. History has no arrow, but it does not go backward, either. The future must be what we make it.