Introduction

With some temporal distance behind us, and much soul searching, let us examine the coup which deposed Donald John Trump in the winter of 2020-2021 and installed Kamala Devi Harris and her sidekick, Joseph Robinette Biden, as the highest Executive officers of these United States. Herein, we’ve a day’s work, for some things were born and many things died that sadsome season. Those three months saw the longtime fissures of the Trump Administration buckle and fail besides decades of contradictions festering within the conservative movement. Under the weight of a stiff and coordinated faction, but not an irresistible one, the unthinkable happened. This unthinkable thing is not that Donald Trump ceased being President. This unthinkable thing is that the long-benighted public sphere, incarnated in the State and asserted in arms in 1775, failed against a spectrum of confederated private interests. It will not rise again within our lives. The Enlightenment ended; Feudalism began anew.

In the months since America’s Swamp creatures inserted the Harris (sic) Administration into the White House, the MAGA spectrum has faded away. We who swore off FoxNews in December have quietly returned to our old habits. We who spit to hear the GOP mentioned in January, find ourselves enthralled in party politics once more. And the earnestness of resolutions, and our fecklessness, cuts both ways. We who saw how Mr. Trump twice insulted, and finally abandoned, his most loyal supporters, now thrill to see his latest interviews on OANN and NewsMax. The media, for their part proud as punch in their complicity in the Biden coup, since January, have published two major articles (Time, “The Secret History” and New Yorker, “Forced To Choose“) broadcasting their role in Trump’s removal. And life goes on; but it does so like in a hangover, or a David Lynch movie.

Those of us who saw what happened still stagger at the enormity of what occurred. Trump’s going and Biden’s coming was more than one office holder switched out for another. What went down was more even than one party using dirty means to get into power. These things have always happened. From Caesar’s Rubicon through Dante’s exile, from Thermidor to the Night of the Long Knives, they will continue to happen in saecula saeculorum. What happened last year was not down and dirty politicking. It was an overthrow. It was nothing more, nothing less.

Yes, the 2020 election was a slow and rolling coup d’état. It was the very sort of thing which America’s archons have executed overseas dozens of times throughout the last half-century. As the dust settles, as the outrages of winter fade, as we slap Trump 2024 stickers on our cars. The world still whirls around, but the Biden Administration is in power and cheaters win.

Making things queerer still, it seems as if few Americans, even those who keep an eye on current events, are aware of the full scope of what happened. We know there was a coup. Nothing is true, if that is not true. After all, no man ever made can sit in a basement for nine months and become President. Political affiliations aside, everyone who followed events knows there was a steal. For all its awful enormity, however, we’ve only the vaguest idea of what happened. This essay is a sketch of that operation.

With the perspective of at least a few months breathing room, we can now lay out the main stepping stones of the Biden operation, sometimes right from the mouths of the spoilers themselves. This exploration honestly admits its ignorance. It is not comprehensive. No doubt later authors will uncover more points, connect more dots; I myself could have doubled this essay’s length for abundance of material. However, a comprehensive treatment of the 2020 Steal is not the end of this paper. It is merely a skeleton. Beyond that, this essay is a work of solidarity. It is an encouragement to my countrymen in the face of six months of media smirking and gaslighting that, yes, they did smell something fishy, and, yes, other people remember it.

When You Point One Finger, Three More Point Back

In the pages ahead I mean to address the specifics which deposed Trump. I will make a concise record, as best I can, of the mad and vicious crew that ultimately seized Federal power. I hope it will assist the general reader in sizing things up; and I especially hope it will give other authors an outline to build on. I also mean to expose and scorn and mock the chinless institutions whose estrogen levels all knew were high, but institutions we at least gave the benefit of the doubt to as being, however lame and incompetent, ever in good faith. The media, the Church, the schools, public academics, and what’s left of the reading public failed their obligations of being social guardians.

More than that lot, though, I mean to expose, however tacitly, what’s become of the broad conservative movement. By this I lasso everyone from Mitch McConnell and CIA-pin wearing Sean Hannity, to the washouts of the Alt Right and Moral Majority, to people like myself who flatter ourselves with different adjectives, thoughtfully chosen no doubt, but who are more or less conservative-adjacent, or woke, or patriot, or alternative. For the lot of us, foundations once destroyed, what can the just do? More than your DNC and your Silicone Valley and your CCP—we blew it. In the months since Harris’ installation, institutional conservatism is tripping over itself to catch up with the Overton Window. What is manifesting itself externally was a long time in coming. How did we not see this?

The Appeal

What built to a crescendo and flopped about and died on the Epiphany was a certain dream of America. I will revisit the specifics of the dearly departed at the end of this essay, but it had to do with hope. To use a word which has pleasantly become popularized this last half-decade, what died was a certain narrative of America. Allow me now a personal appraisal of Donald Trump, and what the Make America Great Again movement meant to me, and how it represented the last hurrah of that narrative. I should think I speak for something of his base.

Always was I a distant fan of Trump. Having moved beyond disgust with the political order to a belief that the government and its agents are in fact enemy occupiers, by 2016 I had ceased to participate in the elections of the color of law UNITED STATES entity. Thus I never rendered Trump any formal voting booth support. After the Bush years, after the continued Obama-era neo-conning of John McCain (of unhappy memory), after so many traffic stops and child removals and drug charges, a certain percentage of a certain sort of men swore off participation in that political system. I am one of them. After having apprehended the morass of the American order, all that is left us is withdrawal. So only from a distance did Trump catch my attention; but catch it he did.

What was invigorating about the man was his willingness to mock the culture of Washington, D.C., particularly its toady media. You see, vast swaths of America had been written out of political discourse. People of European extraction, so-called “white” people, particularly white men, were especially ignored over these last 50 years. Early in Trump’s campaign, in its initial flush of talent, it was commendable for tapping into communities who themselves had written off ever being taken seriously by “mainstream” society. Steve Bannon well deserves the moniker “wizkid,” groundlessly given a decade before to Karl Rove, for his observation that the many dozens of social eddies dismissed by the mainstream “cathedral” of power could be leveraged into a single coordinated opposition movement.

By “mainstream,” of course, I mean the few millions of men more or less concentrated around New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles who frame the mental realities of the remaining 300 millions of Americans, and many overseas souls besides. Those subgroups, which Bannon harnessed, had long despaired of being acknowledged by American culture as even existing, let alone of being taken seriously.

One example of this, well into his presidency, was Donald Trump’s January 2020 appearance at the March For Life. The March is America’s largest annual anti-abortion protest. An always-robust gathering, it had also always been chronically bypassed by the media. Even “allied” groups never took the March to its bosom. The anti-abortion movement has always been an interest of only marginal concern to GOP bigshots, including previous “pro-life” Republican Presidents, men who campaigned on the platform but who barely managed to pump out a pre-recorded clip each winter. But after decades of neglect, there Trump was in 2020.

For someone, such as I, there was a lameness in Trump’s policies. Too much of the Swamp was still around, too much grandstanding about the southern border, and much too much Zionism. More fundamentally, though, there was a democratic streak to Trump which could excuse a thousand faults. Truckers fed up with the red tape of business, wary of the rise of their automated competition, would call up national talk radio with their petitions and pleas. Old timers who still had the icon of old America in their heart would phone national stations to warn Trump or laud him. These were things I heard many times over his four years.

Trump was able to include all sorts. There were people who showed up in the Trump administration whom I had last heard of on niche Evangelical television channels and conservative radio stations, circa 2005. And didn’t my jaw hit the bar one fine afternoon to see Trump’s helicopter landing at the Daytona track! The point is this: One guffaws to think of Clinton or Bush or Obama hearing, let alone acting upon, radio missives from cross-country truckers, but it was never beyond the pale to imagine Donald Trump doing so.

The President liked his “Fox And Friends;” and his fake tan and weird hair were endearing oddities. But whatever was cheesy or lame or quirky about him or the groups he courted, Trump acknowledged the existence of millions of Americans the ruling class thought they had successfully dismissed from “real life” decades ago. Whatever muse tickled Jefferson and Jack and Lincoln and Kennedy, also sang songs of the old America around Trump. It sang democracy. Not NATO democracy, not George Soros democracy did it chant—but the down-home type, school-board democracy, townhall democracy, the Mr. Smith type of democracy. And for that, the cathedral hated him—and for this I loved him.

Air From The Balloon

Life is oft-times covalent. Trump’s empowering of the marginalized and of the working man was grand, but his skewering of the mainstream media was divine. You see, I did not have much to do with the groups he and Bannon courted. It’s been years since I’ve been a fetus, I’ve never been a long-haul trucker. And I don’t have much to say for NASCAR beyond gratitude for the beer and casseroles I’m bid enjoy in large amounts each February during Daytona’s opening day. But across all the groups confederated in the MAGA coalition, a distrust of the national media organs was the common denominator which united them.

It has been five years since Trump first used “fake news” in his Twitter feed (of happy memory). In one brash expression Trump stole from under the noses of his MSM opponents a weapon of theirs; he took and rightly applied what it would take them five years to recover—he took their perceived authority. Trump said aloud what millions had been whispering about for decades: The newsmen are liars. He went on to use the expression “fake news” thousands of times. Trump even created his own “Fake News Awards” in 2018. With the half-decade since its use, overuse, and weaponization, we forget how powerful calling the fake news, fake news first was. We forgot—but the media did not forget.

Background Of The Coup

Context is everything. To begin at the beginning, we must consider the attempt to steal the 2016 Election. Anecdotally, Rick Wiles of TruNews and Alex Jones of InfoWars independently asserted that they witnessed late-night voter spikes, very much of the sort seen in 2020. For whatever reason, these spikes were scotched and the counting returned to a regular tally leading to a Trump win in 2016.

Fast-forward four years. How did Donald Trump walk into 2020 nearly guaranteed a second term only to leave a year later under a barrage of contempt, impeached a second time, deplatformed, with even the hoariest of D.C. insiders hissing about the 25th Amendment being used against him? Americans went mad over that year, that’s why.

As we will see, the mainstream media (MSM) did much to unseat Trump; but the toll of the Coronavirus reaction did much as well. The population’s already shaky reasoning skills were atrophied after a socially distanced year of Netflix-watching and alcohol-drinking. A nation already on edge from a capitalism wherein men regularly live, not just from paycheck-to-paycheck, but from credit-card to credit-card, saw what little economic autonomy they had evaporate, and replaced by a greasy Federal dole. COVID heightened Americans’ placid and mindless tendencies a damn sight more than even us pessimists imagined.

The Crowned And Conquering Child

As regards the election, one of the more meanspirited plot-points happened in June 2020. The actual threat of Coronavirus having passed, Trump was eager to get back to normal. That June, his campaign organized a rally. Those extraordinary events had become quite routine during the Trump years. In one regard he never stopped campaigning because he never stopped the rallies. Perhaps some of Trump’s lackluster policy legacy has to do with his diverted attention. He ought to have stopped campaigning and paid attention to his daily administration duties. It was like he kept trying to play and replay 2016 over again. And while he was static, the Swamp was not.

In any case, after the spring’s Coronavirus panic, one sure sign of normalcy would be to hold another rally. In June one was scheduled in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a heartland city Melania had visited a year before. It was a flop. Superficially spurred on by K-pop fans on the social media site TikToc, teens snapped up all the rally RSVPs. I say superficially because of Mark Moore’s recent report that, “The Pentagon is running a 60,000-strong secret army made up of soldiers, civilians and contractors, who travel the world under false identities embedded in consultancies and name-brand companies— without the knowledge of the American people or most of Congress— according to a report” (New York Post, 5/18/21). I’m led to conclude that many members of this “secret army” haunt social media sites to steer social perception. Whether it was because of teens or the Deep State, Trump went to a sold-out rally and no one showed up. The MSM, for whom reporting had long collapsed into entertainment, sensed blood in the water and set to work mocking the mocked.

BLM et al.

Then there were the riots. Throughout the summer of 2020, there were fierce racial riots whose stakes ramped up as time wore along. It was not enough that these disturbances simmered for months on end. They escalated. Protesters held city centers out West; and new “defund the police” talking points were released by the mainstream press at opportune times. In fact, there was something altogether theatrical about the Black Lives Matter and Antifa protests. Those of us who remember the stage-managed school shootings of the Obama years got a whiff of the same as we watched municipalities drop-off pallets of bricks at choice urban locations.

You’ve Got Mail!

At the end of September, the Deep State flexed its muscle with 500 chinless Defense Department employees signing “An Open Letter To America.” Trump’s greatest offense against the Deep State was not giving the military a new war. It wasn’t enough that he kept the hireling forces of the United States involved in ways overt and covert in Afghanistan and Syria and Yemen and Libya – but by refusing to open fronts in Iran and elsewhere Trump crossed the devotees of Mars. In the lead up to the election, they flexed their muscle. The flattering impartiality which the military loves to remind Americans of was thrown out the window as the Deep State test-ran the coming winter’s narrative.

Once again on January 3rd, immediately before the Confirmation, Elizabeth Cheney, as wicked as her father and doubtless prompted by him, organized all the living Secretaries of Defense to write an op-ed against President Trump. “Joe Biden,” the Open Letter said of a man who had by then sat inert in his basement for seven months, and would do so for another two, “has the character, principles, wisdom, and leadership necessary to address a world on fire.” Stoned, Netflixed Americans bought it; their appetites whetted for more.

Of Laptops And Landmines

Lastly, there was the Hunter Biden cover-up. After the CIA turned Ukraine into an intelligence nest in 2014, in much the same way the states of the Arabian Gulf have been fronts for British intelligence since World War I, Joseph Biden made many connections in the Central European nation. Even in his dotage Biden made sure he was as removed from the financial schemes as possible. In April 2019 an intoxicated Hunter dropped off a laptop in Delaware State. Similar to his October 2018 incident, when a gun of his was found in a dumpster and the FBI attempted to obtain Hunter’s possibly incriminating paperwork, the press went to bat for him. But Hunter was the “bagman,” as Rudy Giuliani said. And this ought to have been investigated.

It was a wash. Most outlets ignored the story; some followed it for a while and let it slip away. Only the New York Post stuck with it. Of course, their doggedness meant nothing because the FBI didn’t investigate, and less law enforcement agencies stonewalled. In its own way, the “conservative” media showed its hand with the Biden story too. On an errand of faux investigative journalism, Tucker Carlson played footsie with the story, vowing to get to the bottom of things. For three weeks he ranted and raved about the story only to give up when his paymasters at Fox told him to stop. It was only at this point when Carlson informed Americans he and Hunter were good friends.

The media is not only propagandistic, it’s also sloppy. It forgets its own trade basics like avoiding conflicts of interest. As Carlson slunk away from the Hunter Biden story, he defended his cowardice by saying, “It was wrong to kick a man when he was down.” This was obfuscation. The laptop scandal was appropriate to pursue because Hunter Biden’s actions weren’t examples of personal flaws, they weren’t lurid sex stories best left in the National Enquirer. Based on the adjective-heavy, heavily veiled comments of Rudy Giuliani and John Paul MacIsaac (the Delaware computer shop owner who received Hunter’s laptop), the photos alleged to be on Biden’s computer largely involved child sexual abuse.

On the heels of Jeffery Epstein’s industrial compromise ring, on the heels of Miles Guo’s revelations of the color-coding of compromised politicians (with those sexually compromised being classed as “yellow”), and considering Joseph Biden’s repeated bragging of his relationships with CCP men like Xi Jinping, the Hunter Biden allegations were ripe for investigation. Since then, in a Stalinisticly-ironic, rub-it-in-your-face move by the cathedral, Hunter Biden, the beneficiary of several miraculous media cover-ups over the years, is now assisting in journalism classes at Tulane University.

The Foreground

The events recounted above comprise the main background of the Steal. Now we turn to the operation itself. Focused especially in the foreground of the 2020 Coup are three events and four. They stand out as especial tipping points in specific areas. They are: Trump’s January 21st, 2020 Davos speech regarding the international order; Mark Esper’s June 1st countermand of Trump’s troop deployment to Washington; and shortly afterwards, the third incident of note, this time in the spiritual realm, was Trump’s holding up of the Holy Bible in front of St. John’s Church. The moment he did that the die was cast against him.

Davos

In January of 2020 Donald Trump attended the meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Along with dozens of heads of state, NGO leaders, and capitalists, Trump conferenced on a diverse array of financial topics, and none too soon. The repos markets had been tottering since the fall. On January 21, Trump spoke to the assembled guests of the WEF. He railed about socialism, he extolled the virtues of American individualism, and he vowed to put nationalism first.

In a room filled with the likes of Klaus Schwab, people who were putting the finishing touches on their Great Reset theories, people who had on their hands a scheme of great potential in the still-distant-though-known Coronavirus, this was too much. For the remainder of his time there, Trump was literally shunned. In the social nooks which offset the main panels, in the kaffeeklatsches and social hours of Davos, Trump found himself standing alone. This event signifies the collapse of Trump legitimacy on the international stage.

Countermand

In June of 2020, came the next institutional shoe to drop. Washington, D.C. joined many American cities that spring in being the focus of racial protests. On the basis of extensive rioting, Donald Trump called in various units of the National Guard to restore order. That very day they were sent home in the midst of continued rioting. What happened? Trump was overwritten.

You see, only two men have the authority to order soldiers in or out of the District of Columbia, the President and the Secretary of Defense. The President made his will known by deploying troops. This leaves the Secretary of Defense, Mark Esper as the only one who could have contradicted the President. This event signifies the collapse of Trump’s authority over the military.

Apre Moi Le Deluge

The third incident was very much the first drop of a deluge to come: FoxNews’ John Roberts’ gaslighting of Kayleigh McEnany on October 1st. There were many tense, unedifying, and childish examples of conduct from both Trump and the press corp over their four years of interacting. With the riots falling back to a simmer, and with the Vote in just one month, on October 1st, McEnany was asked if Trump opposed racism. She responded in the negative, citing some words of his. In a sane world this ought to have been the end of the matter. Fox persisted, asking for more evidence. To this McEnany gave two or three examples. Fox kept asking and asking. Text does not do this queer interaction justice. You ought to watch it to understand how bizarre the exchange was.

More than anything else, the media was responsible for the Harris-Biden (sic) installation, and Fox’s fox Roberts test-ran their gaslighting weapon par excellence. This event signifies the media’s shifting from being hostile to being inimical towards Trump. What would unfold over the next three months would be payback for Trump’s four year of exposing their lies. And lest we forget, come the night of the Vote, it was Fox News which called the election for Biden.

The Rat

The above events are three Rubicon moments in Trump’s deposition, but there is a fourth. The final pylon to fail was Jared Kushner. In December, at the height of the Steal, Kushner who busy in the Middle East grandstanding for Zion with his Abraham Accords. There was no loyalty to the man, no devotion; Kushner ought never to have been allowed within a mile of the White House. Many of Trump’s worst hires and fires came on Kushner’s recommendation. This man was the finest example of the personnel failures which plagued the Trump Administration.

Because he was always in campaign mode, because was too busy skewering the MSM, Trump never had time, or interest, to choose solid men. Instead, he deferred to social climbers like his son-in-law. With rare exceptions such as Kayleigh McEnany, the people Trump had working for him were social climbers. They were either grandstanders in the moment, like Kushner or Pompeo, or they were trimming their sails for their post-Trump careers, like Mark Milley. In any case, Jared Kushner’s effeminate self-promotion, when his boss and father-in-law was in need of all hands-on deck, signifies the collapse of Trump’s inner circle.

The Steal

As to the DNC heist of November 2020 itself, that is a topic beyond the scope of this outline. Like the Fall of Troy, around which both The Iliad and The Odyssey revolve, but which is never directly described, I leave our late national blot silently brooding over every word of this essay, but never dissect it head on. For specifics on this matter, I direct your attention to Michael Lindell’s three features on this topic, Absolute Proof, Absolute Interference, and Scientific Proof. All are also available for free on his website.

And, as this essay goes to press, the ongoing audits in Arizona and Georgia give hope that the truth will out.

Pushback

With each electoral safety bulwark failing, as fall turned into winter, confidence in increasingly archaic schemes and legalities rose. The first hope to fail was in the realm of citizen protests and journalism. Getting the message out in the media, filing affidavits, and making the record were the orders of the day. There was plenty of work to do, as thousands of Americans came forward to document electoral errata. This course climaxed, sputtered, and failed on November 25.

On the day before Thanksgiving, a most poorly timed event, the Trump, team headed by Rudy Giuliani, gathered hundreds of men in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to testify to the many instances of voter fraud witnessed throughout the county. However, one month into The Steal, the MSM realized that if they could mock the charge of voter fraud in se, if they could preface what mentions they couldn’t ignore outright with “unfounded” or “not widespread,” or “lies,” there was nothing, absolutely nothing, which could stop their narrative from winning the day. An unlettered and deracinated American public could only sit and ingest what it was told.

More than anything else, Joseph Biden’s installation was the work of the media. There was a constellation of fellow-travelers and allies, but 2020 was predominantly a battle of perception; and that perception was ironclad by the press. It was the apotheosis of Edward Bernays’ work and Madison Avenue’s century of note-taking. Needless to say, despite hundreds of sworn testimonies, the Gettysburg event fizzled. Thousands of filings were thrown out of nationwide Bar Association courts in the following weeks.

The coup had works in the open, but it also did works in secret. On November 21, one of those quiet efforts leaked out. That day a story appeared in various sources about Emily Murphy, the head of the General Services Administration. It told of how Trump finally released funds for the Biden Transition Team to use because she was being threatened to do so. She wrote to the Biden Team,

I was never directly or indirectly pressured by any Executive Branch official—including those who work at the White House or GSA—with regard to the substance or timing of my decision. To be clear, I did not receive any direction to delay my determination. I did, however, receive threats online, by phone, and by mail directed at my safety, my family, my staff, and even my pets in an effort to coerce me into making this determination prematurely. Even in the face of thousands of threats, I always remained committed to upholding the law.

For the peace of a harried bureaucrat ,Trump gave permission to release money to the spoilers. Like at the dummy Tulsa rally that spring, the MSM spun an abuse for their ends. Trump was conceding the election, so the story went. Score one for gaslighting.

The next hope to fail was the Presidential Election on December 14. Before detailing the Election vis. Trump, I must pause and clarify the official process whereby a man enters the Federal Executive office in America. There are three events of increasing gravity which are prescribed for this. Funnily enough, as their importance grows, their public awareness diminishes. Most American believe things begin and end on one day in November. In fact there are three stages a man must successfully go through to be President. These are the Presidential Vote (November), the Presidential Election (December), and the Presidential Confirmation (January). Things are not made easy by the fact that people refer interchangeably to the Vote as the Election, by which they mean the early November event.

What follows is a generalization, which I detailed in my recent series on “We, The People.” Briefly, the Vote recommends to the state Electors whom they should select for that state’s slate of electors to choose. It must be absolutely understood that the Vote is simply a suggestion, it does not oblige the Electors’ decisions whatsoever. However, typically, they do follow these suggestions. After the Election, there follows the Confirmation. This January event is the final chance to troubleshoot any procedural objections. It was in the context of the Confirmation that the riot of January 6th happened.

The point is that the media’s gaslighting and the putzing about of the Trump team throughout November were annoying but they were not particularly alarming because we who were watching things assumed all would be righted in the Election. The Electors are the People in “We, the People;” they are the Patricians; they are the archons; they are the owners of the country. Whatever the weirdness or objectionability of their system, we who took the time to learn the system assumed they were the adults in the room. You can rig a voting machine, you can’t rig a Person. We assumed they were of tougher mettle than the party pukes who stalk around polling stations with sacks of money and brass knuckles. After all the Electors are effectively those with the greatest material share in the country; they are the biggest landholders and businessmen throughout the 50 states. Trump did many things poorly, but he did well for America’s moneymen. The assumption was they would back him. We assumed wrong.

You know, six months on, having thought about this some, I don’t think the Electors needed to be as threatened or bribed to vote for Biden as I once did. Like with so much else, we didn’t realize how far down the rot was. So the Election came and the Election went, and Biden was elected that December. Michigan’s Republican delegation made a stink, showing up at the State House and being locked out, and there was some talk down in Georgia of the same; but it came to nothing. When the media and the offices of state decide to stonewall there is nothing lawful men can do.

After such serious official collapses, the tone of Trump supporters changed. A lot gave up hope; but some of the well-read remembered that there was a third stage to the choice of an Executive, the Confirmation. If few Americans know the difference between the Vote and the Election, fewer still are aware of the Confirmation. This is Congress’s opportunity to review the preceding two stages, and to voice any concerns over any irregularities raised. It is around this least conventionally “political” of the three stages, this emergency valve, where attention turned as Christmas approached.

As the MSM couldn’t altogether ignore the discontent throughout the country, they were forced to acknowledge it. It was at this time, late December, that some voices arose on the national scene, who threw in their lot with the Trump defense. They were grandstanders in retrospect, trimmers some, useless men with big mouths others, but around the likes of Rand Paul, Ted Cruz, and Mike Pence, hope began to grow that various emergency procedures might be implemented on January 6.

To Stir The Pot

Even if Trump showed more than a half-hearted desire to beat back the Steal, which he never did, there was no hope that the right would out, following the Election. We will return to the specific hopes and theories which Americans began placing in the sixth of January, the date of the Confirmation, in a little bit. I wish now to address the role of intelligence agencies in the coup. Americans, whose political system excels in overthrowing governments, who live in a decade of such overthrows, seem strangely ambivalent to the possibility of those self-same agencies doing as much in America.

What was the situation by late December? The Vote was stolen in plain sight. Neither the Electors nor the courts were interested in hearing out thousands of Americans who reported seeing funny business at that event. The media was in high psyops mode, and each day they dialed up their efforts. Trump’s defense was split and sloppy, and Trump himself was lukewarm when he wasn’t silent. As outraged Americans began planning their third and biggest rally, two things appeared on the scene. The first was talk of a civil war, the second was QAnon. Both were manifest works of the Deep State, and in both instances conservatives walked into a trap.

Ideas of civil strife gripping America were deliberately seeded during the opening months of 2020. The Atlantic gave over their entire December 2019 issue to the topic. Their “How To Stop A Civil War” publication was a textbook case of seeding a narrative. No one was talking of such before The Atlantic brought it up. One year, one overblown sickness, and one rent-a-mob summer later, and the talk was reintroduced.

The Protect Democracy Project ran workshops in June and October of 2020. In it, hundreds former and present bureaucrats from the Military Industrial Complex war-gamed the possibility of unrest accompanying the fall’s electoral process. These scenarios went under the heading of the Transition Integrity Project. The participants found there to be a high chance of civil unrest following the vote. If this sort of thing sounds familiar, if there’s something George Soros-esque about an outfit called “Protect Democracy,” the exercises it holds, and their pipeline to the press, it’s because it is run by Ian Bassin, a former member of the Obama White House and a man who pose-by-pose is a carbon copy of Barry Soetero. You see, Larry Sinclair’s boyfriend and his epigones never left D.C. From the moment Trump was elected, Obama and the Deep State and the Never Trumpers were at work for 2020. The point is, worked into the mix of COVID and electoral tension, the possibility of catastrophic violence was introduced. It is to the discredit of the late, great “alternative media” that they took the Protect Democracy bait. Nobody bothered to check to see who Protect Democracy was. It was a juicy story, so the alt press ran with it.

The next spoiler which came along was QAnon. The epitome of controlled opposition from the same sorts who built up ISIS, when the Q operation was through, Trump supporters seemed madder than an outhouse rat. As each hope failed, the Q people would double down—“trust the plan,” and schedule the next knock-out blow to the Deep State. For example, on the day of Harris’ inauguration, Q types were insisting the fencing around the Capitol was to keep the lawmakers in (because they were all surreptitiously under arrest); the military was going to arrest Biden and conduct a new election, and Trump would be back in office come mid-March. As of my May 2021 composition of this writing, in all seriousness I have been assured Donald Trump will be restored on August 15th. Hope springs eternal, or from Langley.

Fissures Forming

As these structural failings were happening, as the Vote’s steal went unchallenged throughout the states, as the MSM railroaded the perception that Biden’s win was unchallenged by all but madmen, as the Electors certified November’s crime, the response on the part of Donald Trump was jerky, erratic, and imprecise.

Firstly, it seems that a similar steal was affected in 2016. It is more speculative than 2020, but from what reports we have, the same kind of voter spikes happened, and they happened in the same states no less. In fact, the bizarre behavior of what’s called, rightly or wrongly, the “institutional left” during the four years of the Trump Administration only makes sense if they were expecting to have won only to have the prize snatched from under their noses at the last minute. What else explains their genuine hatred for a man who was pretty much a milquetoast, albeit loudmouth, conservative?

Background and questions aside, when Trump’s term finally organized a response, it was sloppy from the word go. At their first press conference within a week of the Vote, and a number of times in the following weeks, they were unwilling to provide any evidence of voter fraud. This incompetence is unbelievable, given that anyone could tune in half the radio shows in the county which were featuring men who saw paper shredding trucks at polling booths, vote minders boarding up windows, and clerks changing ballot rules at the last minute. The defense only went downhill from there. Soon Sydney Powell, and her meatier charges of overseas electoral tampering, was shown the door. And indeed, before all was said and done, Rudy Giuliani’s slowly dripping hair dye was the truest summary of Trump’s defense, and indeed of American conservatism.

Prester John

By late December, there began to be a discernible irrationality amongst Trump supporters. As the Book of Ecclesiastes says, oppression makes a wise man mad (7:7). As the ordinary channels of redress buckled under the bribes and bullies and caresses of the DNC and their confederates, those who saw what was happening began to place their hopes in increasingly far-flung hopes whereby the Trump Administration would come out on top.

This tendency is actually a regular feature through history. During the Crusades, as the situation of besieged Outremer darkened, the Christians of Europe began to place their hopes in “Prester John.” A confusion of Marco Polo’s far-flung observations and Eastern lacunae, John was supposed to be a mighty Ethiopian priest-king who was coming to the rescue of his Palestinian co-religionists at any moment. Alas, Fr. John never made the rounds. Close on the historical heels of fantasies about Trump’s survival were things like the 1890s Indians Ghost Dance and Hitler’s hopeless breakouts around Berlin during the Second World War. As in history, so with Trump’s supporters. The more the spoilers succeeded, the greater became the hopes of the MAGA train.

It is easy to mock this tendency. However, concerning the stolen election, recall that in the late fall of 2020, the alternatives to fantastical hopes were to resign oneself to (1) sitting by as a lawless clique seized power, and (2) observing that fellow Americans were either largely in agreement with such criminality (unlikely) or too apathetic to care (likely).

Questions

Whatever the case may be, if a 2016 steal was the case, as it appears to have been the case, why didn’t Trump’s men provide against it? Why did they not shore up the other routes beyond the Vote? Forget about the courts, the media, the Election, and the Confirmation, they did not even seem to do much to avoid in 2020 the kind of hanky-panky Vote fraud which happened in 2016.

Surely, they must have known the DNC et al. were going to deploy in 2020 fossers not only against the Vote, like they did with Hilary Clinton, but also against every subsequent route of redress? I have no answer to this question, beyond a speculation that Trump & Co. were depending on an incontrovertibly high popular vote to win the day, support so plain upon tables that any DNC sliminess in the courts, the Election, etc. would be risible.

There is another option I can’t pretend hasn’t crossed my mind. Worse by far than incompetence—that perhaps Trump threw the election. Perhaps it was all theater; perhaps the MAGA movement was itself controlled opposition all along. After all, what did the Trump train do for Red State America? He didn’t stop the Agenda. Everything he attempted to implement was rolled back within hours, within days of Harris’ (sic) installation, and the most ideologically solid conservatives, and few there be, are well on their way to being classified as terrorists by the Bar Association system. Was Trump a Pied Piper?

I hesitate to choose this explanation because while there was plenty of theater from both Trump and his adversaries, there were too many examples of disrespect and anger between them which jumped the script. Nancy Pelosi tearing up Trump’s speech during the State of the Union,=; Jim Acosta’s behavior in press conferences; the cruel mockery of Sarah Sanders’ appearance; and the lockstep coordination of Silicon Valley and America’s internal spy agencies following the January 6th riot were all events which exceeded, far exceeded, the type of Wrestlemania “antagonisms” which accent typical politics.

The third option is that Trump realized the enormity of what the DNC did, and he realized that neither the Republican Party nor the feckless men who worked in his Administration (his own hires, let it be said) were going to support him, and he lost heart by late November.

Of these three options, I believe Trump’s anemic response to the coup is explained to some degree by options one and three.

The messaging and execution of Trump’s legal defense was erratic and factional. It was a microcosm of the erratic staffing of his four years in office. Divisions formed early within Trump’s defense. When things coalesced by late December(!), Rudy Giuliani led the official team. The guts of their objection revolved around mail-in ballot fraud.

Sidney Powell had been cut loose by then. Soon to be joined by Lin Wood, this lesser group focused on the errata surrounding the voting machines, and the interference of American intelligence overseas in the Vote. It would not be until the eleventh hour of January 15, when Mike Lindell of My Pillow fame, clawed his way past grudging White House aides, when what was left of the Trump Administration backed objections to the graver findings from November (as compared to the child’s play about gerrymandering Guiliani was pursuing). Again we must ask why Donald Trump, who ran a nation with a long history of staging coups, did not anticipate such a thing happening to him?

Behind The Scenes

Then on December 18th, the previous four years of bad advice, distracted hiring, and self-serving hacks erupted in one disastrous meeting. For the remaining month of Trump’s presidency, there would effectively be no administration in any meaningful sense. That day there was a collision between the MAGA men, as we might call them, those who generally believed in Trump as a unifier of the conservative spectrum and who proximately acknowledged the Steal, and the trimmers, those who came from the Swamp, remained in the Swamp, and who will die in the Swamp. Additionally, that December day, there was a collision between the two wings of Trump’s election defense, as represented by Rudy Giuliani and Sydney Powell. Something of the chaos of that event leaked out. As reported by Business Insider:

You’re quitting! You’re a quitter! You’re not fighting!” [Michael] Flynn said of [Eric] Herschmann before turning to Trump and adding, “Sir, we need fighters.”

According to Axios, Herschmann responded, “Why the f— do you keep standing up and screaming at me?”

He added: “If you want to come over here, come over here. If not, sit your ass down.”

After the Allies opened their 1918 Hundred Days’ offensive, German general Erich Ludendorff reported to Kaiser Wilhelm that the war was unwinnable. He called it Germany’s “Black Day.” After the December 18th meeting, there was no hope of staunching the Steal. Everything after is postscript: The Confirmation, the riot, the reshuffling of the Defense and Homeland Security heads, the second impeachment, America.

As Things Stand

Donald Trump spent four years trying to recreate a set-piece reenactment of 2016, while his opponents spent their time perfecting their 2020 plan. The spoilers provided against every possible route of redress, while Trump was grandstanding and getting into Twitter fights. Trump was surrounded by the lowest, most useless sorts of men, all of them his own choices. The list of such men starts with Michael Pence.

By the time of the heated pre-Christmas meeting, Trump had brushed-off two massive rallies of his most devoted supporters, including many hundreds of men willing to testify to the crimes of November. Instead, Trump chose to spend his time campaigning for the likes of Kelly Loeffler, a woman who, 24 hours after Trump had his arm around her on a rally stage in Georgia, did not have the guts or gratitude to raise a stink about the offense done to him. His official defense team was limp-wristed and confused. In those three months, from the Vote to Harris’ White Entry, Donald Trump never knew where to exert his energy.

Where Things Stand

In the meta-look, one term or two, Donald Trump was a sandcastle at tide’s rise. And he was merely a sandcastle at one part of a very long beach, the political section, itself not even the most important part. In the vaunted “first hundred days” of the Harris Administration, we’ve seen enough to see where things are going. The wars are back on, the bailouts are back, the cultural manipulation moves apace. The Swamp stinks worse than it did before. The conservative movement as we knew it, something which orbited around the GOP and the Church and talk radio, is dead. It was betrayed by the aforementioned, and other false friends besides.

What remains of structural conservativism busies itself creating home pages on a hundred alt social media sites, pages soon to be deleted, and moving en masse to “Red States,” a clueless rehash of Libertarian fads from 20 years ago. Individuals of that persuasion content themselves with daily rosaries, social media reposts, and doubling down on the paranoia and anti-intellectualism which first threw them in the hole they’re in now. And so it goes. An Agenda which has marshalled ambivalence for its ends, and a resistance which doesn’t know its nose from its elbow.

John Coleman co-hosts Christian History & Ideas, and is the founder of Apocatastasis: An Institute for the Humanities, an alternative college and high school in New Milford, Connecticut. Apocatastasis is a school focused on studying the Western humanities in an integrated fashion, while at the same time adjusting to the changing educational field. Information about the college can be found at its website.

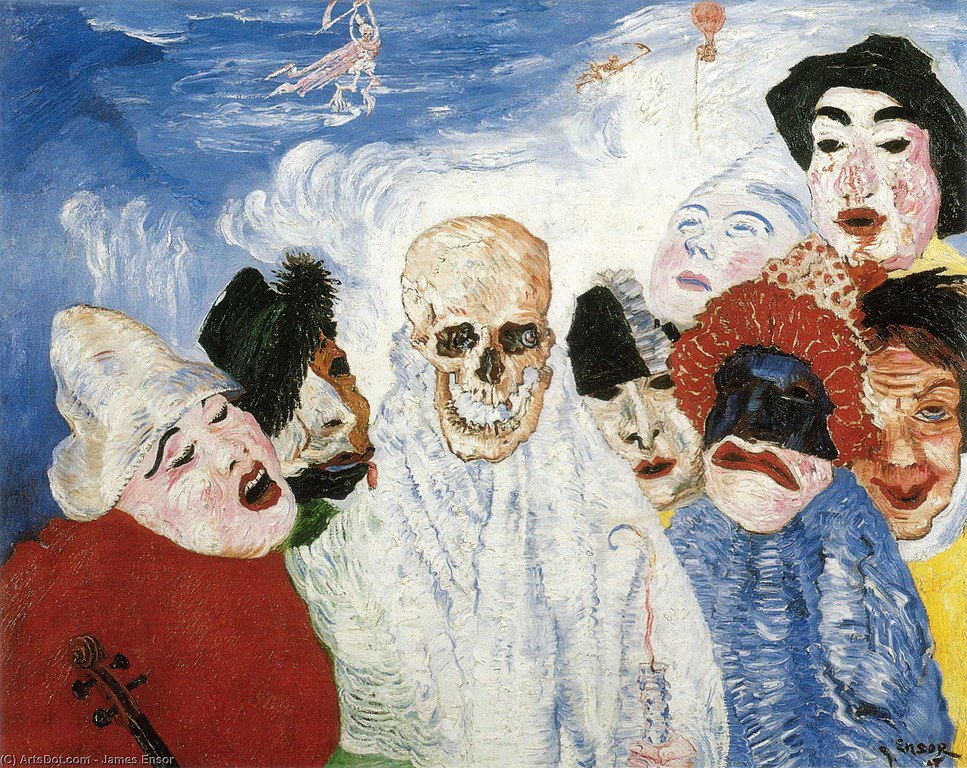

The featured image shows, Death and the Masks,” by James Ensor; painted in 1897.