The most ancient roots of the West lie in one place.

The society in which we live, a liberal democracy, is the result not of events that happened all over the world – rather, it is the result of events that happened in just one country. ancient Greece.

We are who we are not because of what happened in ancient China, Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt or India (essential as the histories of these places are to our knowledge of the world). Despite the passage of millennia, we still live in the world invented by the ancient Greeks.

And because of the influence and spread of western technology, the entire globe has now been impacted by these Greeks of long ago.

There is a reason why we want all people to be free; why we think more democracy is a good thing; why we worry about the environment; why we have immense faith in our ability to come up with solutions no matter how great the problem; why we believe education to be crucial to building a good life; why we seek self-respect.

And this reason is simply stated: we have inherited – not created – a particular habit of mind, a way of looking at the world.

We live within a set of values that constantly encourage us to depend on reason, to seek out moderation and distrust excess, to live a disciplined life, to demand responsibility in politics, to strive for clarity of thought and ideas, to respect everyone and everything, including nature and the environment, and most of all to cherish and promote freedom.

This is our inheritance from the ancient Greeks. We need to study them in order to learn and relearn about our intellectual, esthetic and moral inheritance – so that we might meaningfully add to it so that it may continue in the vast project of building the goodness of our society.

This is why we need to study the Greeks, because through them we come to study ourselves.

And what about the Romans? They were the people that allowed Greek learning to be made available to the world.

The ancient Romans adopted the Greek habit of mind and through their empire, which stretched from the borders of Scotland to the borders of Iran, they passed on this inheritance to all the people that lived within these borders.

Thus, in studying the Romans, we come to understand how very difficult it has been for ideas, which we may take for granted, to come down to us. Whereas the ancient Greeks created the world we live in, the ancient Romans facilitated it by giving universality to the Greek habit of mind.

Thus, to study both these civilizations is to fully understand our own.

Prehistoric human settlement in the Greek peninsula stretches back to the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods. By the time of the Bronze Age, different types of pottery demarcates the various phases of material culture.

For the sake of convenience, historians have used these various types of pottery to work out a chronology of Greek prehistory. And because Greece is not only the peninsular mainland, but also the islands in the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas, the pottery is sorted out by different regions.

Thus, the Bronze Age in the mainland of Greece is classified as Helladic (from 1550 B.C. to 1000 B.C.).

On the island of Crete, the Bronze Age is labeled Minoan (from 3000 B.C. to about 1450 B.C.). And on the various islands of the Aegean, the Bronze Age is referred to as Cycladic, where it begins around 3000 B.C. and lasts until about 2000 B.C., at which time the culture of the Cyclades is absorbed into the greater Minoan civilization.

The earliest expression of Bronze Age civilization in Europe is found on the island of Crete, where a brilliant culture flourished from about 2700 B.C. to around 1450 B.C.

It was brought to light in 1900 by the English archaeologist, Sir Arthur Evans, who excavated a large complex at Knossos, which he called a “palace.”

But the “palace” he found was different from what we might imagine. It was a warren of maze-like adjoining rooms, where people lived and worked, and where oil, wine and grain were stored in massive clay jars, some as high as six feet. It was likely an administrative center, plus a warehouse.

The labyrinthine layout of the palace suggested the name, Minoan,” to Evans, after the Greek myth of King Minos of Crete, who had built a maze to hide the Minotaur, the half-man, half-bull offspring of his wife, Pasiphae, who had fallen in love, and then coupled, with a white bull.

The many wall-paintings from the palace give indication that the cult of the bull was prevalent among the ancient Cretans – the best example being the ritual or sport of “bull-leaping,” in which young men and women grasped the horns of a charging bull and leaped over its back to land behind the animal.

It is difficult to say whether this was done as sport, or perhaps even as a religious dance. We cannot know since we have no contemporary written explanation for this display.

Evans also found thousands of clay tablets with writing on them. The writing was in two versions of the same script. The first version he labeled Linear A, and the second he called Linear B.

The only problem was that he could read neither. It would not be until 1952 that Michael Ventris finally deciphered Linear B and found the many texts in this script to be the earliest form of the Greek language.

When the same rules of decipherment were applied to Linear A, however, it was found to be a curious language that was not Greek at all, nor was it a language that could be placed in any known family group.

Perhaps as further work is done on Linear A, it might disclose more of its secrets. But for now, the Minoan world is mysterious to us, because all we have are its material remains.

However, the more intriguing question that arises from the evidence we have is – how did the earliest form of the Greek language get mixed with a non-Greek language in the palace at Knossos?

This question points us northwards to the mainland of Greece, and to a city known as Mycenae.

The speakers of the earliest form of Greek were the Mycenaeans, who were given their name from the city they inhabited, namely, Mycenae, where the German archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann, in 1876, found a well-developed civilization, with a ruling warrior aristocracy who lived in fortified towns built on hilltops.

Aside from Mycenae, the towns of Athens (a relatively unimportant place at this early time), Pylos, Tiryns, Iolkos and Orchomenus were also part of Mycenaean culture, which established itself around 1900 B.C. and endured until 1200 B.C.

Schliemann’s excavations revealed a circle of shaft-graves, in which the dead were buried standing up, and in which were found large quantities of weapons as well as gold objects, from funerary masks to goblets and jewelry.

He also found evidence for the domesticated horse and the chariot – and, most important of all, there were found clay tablets with Linear B written on them, which would be deciphered as the earliest form of the Greek language.

All these discoveries led to an important question – where did the Greeks come from because their language ultimately is not native to the land now known as Greece.

If we examine the archaeological record of the time just before the Mycenaean age, we find massive destruction that lasted about a hundred years from 2200 B.C. to about 2100 B.C.

And the material remains of the people that established themselves after the destruction were markedly different from those that lived in these same areas before.

It is to this deep destruction that we can link the “coming of the Greeks,” a phrase much used by historians.

So, where did the Greeks come from?

The clues before us are two-fold: material and intellectual culture. The excavations at Mycenae yield several essential clues: chariot parts, horse tack, skeletal remains of horses, weapons and pottery; plus, there is also the fact that these people were speakers of early Greek, as demonstrated by the Linear B texts.

The recent discovery of the Griffin Warrior from the Mycenaean Age also points to the richness of the material remains from the era, and further offers hints as to the origin of Greek culture.

These clues points to one conclusion. The earliest Greeks, that is, the Mycenaeans, came as invaders, likely from the north, and they destroyed what they found and took control and began to build their own fortified towns.

And we know that they are invaders because of their language, which is Indo-European – and this tells us that these early Greeks came from elsewhere, since the origin of the Indo-European languages is in a place quite a bit distant from Greece.

In the latter years of the third millennium, there were massive Indo-European invasions throughout Eurasia. This is evidenced by the spread of Indo-European languages, and by DNA analysis.

The origin of the Indo-Europeans is likely in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, what historians call the “Kurgan culture.” “Kurgan” refers to the grave mounds under which these early Indo-Europeans buried their dead.

From this point of origin, the Indo-Europeans overran large parts of Europe and some parts of Asia. They were able to be do this because they had domesticated the horse, had invented the chariot, and perfected the composite bow.

The languages they spoke were closely related and to this day comprise the largest family group in the world.

Thus, the indo-European languages consist of the ancient languages (and their modern-day descendants) of northern India (Vedic and Sanskrit) and Persia (Avestan and modern Persian), the Slavic languages, the Baltic languages (Lithuanian and Latvian), Celtic and the Italic (Latin and its descendants, such as, French and Italian), the Germanic languages (such as, German and English), and of course Greek (interestingly, Greek did not create any descendant languages).

This affinity between languages extends further into intellectual culture, since language is the bearer of culture, thus there is a pronounced similarity, for example, among the myths of the various Indo-European peoples – these myths explain and stratify reality.

The Indo-Europeans who veered into Greece called themselves Achaeans, who spoke a very early form of Greek, a form that has some of the closest affinities to Vedic and Sanskrit.

The Achaeans subdued the various non-Indo-European peoples that were living in Greece (the Minoans) and set up suzerainty over them.

The outcome of this process was what we call the Mycenaean civilization, which Schliemann excavated, as noted earlier. The Mycenaeans were known for their warrior culture, in which the chariot and the horse were much valued.

By 1600 B.C. they were established and thrived not only in Greece but also in parts of what is now Turkey.

Around 1450 B.C. these Mycenaeans conquered Crete and destroyed the Minoan civilization.

But they were not above learning civilized ways from the people they had conquered – for they adapted the art of writing invented by the Minoans to their own language, since the Minoan alphabet was not suited for an Indo-European language which had many consonantal clusters, whereas the alphabet of the Minoans (Linear A) was syllablic (each letter represented a consonant and a vowel together).

It is for this reason that Sir Arthur Evans found texts written in both Linear A and Linear B at Knossos, since the Mycenaeans assumed control of this palace structure after their take-over of Crete; and in time they came to use the Linear A alphabet as their own.

The rule of the Mycenaeans in Greece and in Crete was fated. It was destroyed during a catastrophic period in Eurasian history known as “the Bronze Age Collapse,” in which a total of forty-seven important cities were attacked, their inhabitants either killed or enslaved, and the places burned to the ground.

The swath of burned down cities is large and covers Syria, the Levant, Anatolia, Cyprus, Crete and Greece. From 1200 B.C. to about 1150 B.C., there were destructive raids by newer groups of Indo-European peoples, who had developed an innovative method of warfare, which gave them a greater advantage over the armies that these doomed cities could muster.

We have to keep in mind that the first Indo-European invasions, which saw the establishment of the Mycenaeans in Greece and Crete, were the result of the chariot and the composite bow.

The invasions which put an end to the Bronze Age were also successful because of a new type of warfare – the use of infantry armed with a long lance and a broad sword.

The metal for these weapons was iron. Bronze weapons were no match for these iron lances and swords, and the chariots became useless, too, since the foot-soldiers could easily disable a charioteer with their long lances by spearing the warriors that rode inside. The Bronze Age was violently brought to an end by iron weapons.

Thus, the Iron Age begins with an enormous catastrophe – a total collapse of civilization.

Once the large cities and palaces were destroyed, they were replaced by small communities of a few individuals; and these were often located not in the plains, but high in the uplands.

The Iron Age is also known as the Ancient Dark Age, because civilization, or city life, disappeared.

The new group of Indo-Europeans, who invaded Greece in the twelfth century B.C. and put an end to the Mycenaeans, are known as the Dorians; their name likely derives from the early Greek word, doru, which was the long wooden lance that they carried.

It is from the various dialects of these new invaders, plus Linear B that the Greek language developed.

The invading people destroyed civilization and did not value living in palaces or large cities. Instead, they chose to live in smaller communities that had fewer luxuries and fineries which we usually associate with civilization.

There is also evidence of depopulation since the settlements that replace the burned cities and palaces tend to be small and few. Pottery is no longer finely and elaborately decorated but has simple geometric patterns.

The Dark Age lasted from 1200 B.C. to 800 B.C. and can be summarized as a period of petty tribalism.

However, we know a lot about this period because of two significant literary works that describe the people involved in these invasions.

They are the two poems by the legendary poet Homer, namely, The Iliad and The Odyssey. In fact, the story of the siege of Troy may be a memory of the Bronze Age Collapse.

It is with Homer that we enter into recorded Greek history, known as the Archaic period.

From 800 B.C. to 480 B.C., Greece underwent revolutionary changes and began to emerge from its tribal era. This period saw the growth of cities once more, which was fueled by an increase in population and the expansion of commercial trade.

The idea of people being ruled by kings vanished and was replaced by a new form of government, the city-state, in which people sought not to be warrior-heroes, but good citizens.

As a result, there was a focus on refining city life, which led to great achievements in architecture, sculpture, art, commercial relations and trade, politics, and intellectual and cultural life.

Because of larger population colonies were established outside of Greece: in Sicily, southern Italy, eastern parts of Spain, along the southern coastline of France, at Cyrenaica in North Africa, in the Hellespont, and along the Black Sea.

All this was possible because of the growth of technological knowledge, especially in the areas of shipbuilding and seafaring, as well as developments of a new form of government, the polis, or the city-state, which came about as a result of synoecism, or the gathering of various villages into single political entities or units.

It was because of advances in the archaic period that Greek city-states prepared themselves for the maturity and perfection that they would achieve in the fifth century B.C.

And the most important of these cities was Athens, whose citizens radically and permanently changed the world around them – so much so that the ideas implemented by these men and the structures established by them are the very ones in which we still live.

Civilization would never really look back, because of what was achieved in Athens in the fifth century B.C.

This is the origin of the West.

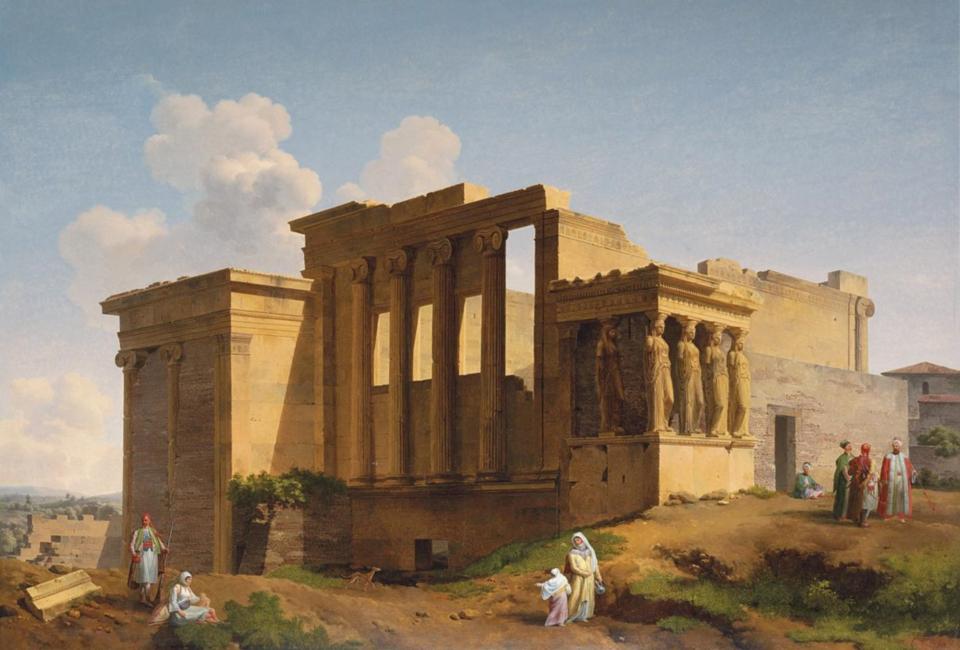

The photo shows, “The Erechtheion on the Acropolis,” by Lancelot-Theodore Turpin de Crisse, painted in 1805.