This excerpt is from Essays in Satire, by Ronald A. Knox, which was published in 1930. Monsignor Knox (888-1957) was a widely respected English Catholic theologian, writer, thinker, and radio broadcaster. Among his many contributions to knowledge and the world of ideas is his translation of the entire Bible (known as the Knox Bible). He also famously wrote crime fiction and began the Sherlockian tradition of the “Grand Game,” with the publication of, “Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes,” in 1911, when he was 23 years old and still a student at Oxford, and which we have also now published.

Famously, on January 16th, 1926, he presented Broadcasting the Barricades, which we have republished, which was a “live” radio coverage of a supposed a revolution in London, with an attack on the Houses of Parliament the destruction of Big Ben, and the hanging of the Minister of Traffic as well as other mayhe, m. It set off a nation-wide panic. This broadcast became the model for Orson Wells’ no-less famous “War of the Worlds.”

Whoever shall tum up in a modern encyclopaedia the article on hummingbirds—whether from a disinterested curiosity about these brightly-coloured creatures, or from the more commonplace motive of identifying a clue in a crossword—will find a curious surprise awaiting him at the end of it. He will find that the succeeding paragraph deals with the geological formation known as a humus; or if his encyclopaedia be somewhat more exhaustive, with the quaintly-named genius of Humperdinck. What will excite his speculation is, of course, the fact that no attempt is made by his author to deal with humour.

Humour, for the encyclopaedist, is non-existent; and that means that no book has ever been written on the subject of humour; else the ingenious Caledonian who retails culture to us at the rate of five guineas a column would inevitably have boiled it down for us ere this. The great history of Humour in three volumes, dedicated by permission to the Bishop of Much Wenlock, still remains to be written. And that fact, in its turn, is doubly significant. It means, in the first place, that humour, in our sense of the word, is a relatively modem phenomenon; the idea of submitting it to exhaustive analysis did not, for example, present itself to the patient genius of John Stuart Mill. And at the same time it is an uncommonly awkward and elusive subject to tackle, or why have we no up-to-date guide to it from the hand of Mr. Arnold Bennett?

Assuredly this neglect is not due to any want of intrinsic importance. For humour, frown upon it as you will, is nothing less than a fresh window of the soul. Through that window we see, not indeed a different world, but the familiar world of our experience distorted as if by the magic of some tricksy sprite. It is a plate-glass window, which turns all our earnest, toiling fellow-mortals into figures of fun. If a man awoke to it of a sudden, it would be an enlightenment of his vision no less real than if a man who had hitherto seen life only in black and grey should be suddenly gifted with the experience of colour. More, even, than this; the sense of humour is a man’s inseparable playmate, allowing him, for better or worse, no solitude anywhere. In crowded railway-carriages, in the lonely watches of a sleepless night, even in the dentist’s chair, the sense of humour is at your side, full of elfin suggestions. Do you go to Church? He will patter up the aisle alongside of you, never more at home, never more alert, than when the spacious silences of worship and the solemn purple of prelates enjoins reverence. I could become lyrical, if I had time, over the sense of humour, what it does for men and how it undoes them, what comfort lies in its companionship, and what menace. Enough to say that if I had the writing of an encyclopaedia the humming-birds should be made to look foolish.

Humour has been treated, perhaps, twice in literature; once in the preface to Meredith’s Egoist, and once in Mr. Chesterton’s book, The Napoleon of Netting Hill. What it is still remains a mystery. Easy enough to distinguish it from its neighbours in the scale of values: with wit, for example, it has nothing to do. For wit is first and last a matter of expression. Latin, of all languages, is the best vehicle of wit, the worst of humour. You cannot think a witty thought, even, without thinking in words. But humour can be wordless; there are thoughts that lie too deep for laughter itself.

In this essay I mean to treat humour as it compares with and contrasts with satire, a more delicate distinction. But first let us make an attempt, Aristotle-wise, to pin down the thing itself with some random stab of definition. Let us say that the sphere of humour is, predominantly, Man and his activities, considered in circumstances so incongruous, so unexpectedly incongruous, as to detract from their human dignity. Thus, the prime source of humour is a madman or a drunkard; either of these wears the semblance of a man without enjoying the full use of that rational faculty which is man’s definition. A foreigner, too, is always funny: he dresses, but does not dress right; makes sounds, but not the right sounds. A man falling down on a frosty day is funny, because he has unexpectedly abandoned that upright walk which is man’s glory as a biped. All these things are funny, of course, only from a certain angle; not, for example, from the angle of ninety degrees, which is described by the man who falls down. But amusement is habitually derived from such situations; and in each case it is a human victim that is demanded for the sacrifice.

It is possible, in the mythological manner to substitute an animal victim, but only if the animal be falsely invested with the attributes of humanity. There is nothing at all funny about a horse falling down. A monkey making faces, a cat at play, amuse us only because we feign to ourselves that the brute is rational; to that fiction we are accustomed from childhood. Only Man has dignity; only man, therefore, can be funny. Whether there could have been humour even in human fortunes but for the Fall of Adam is a problem which might profitably have been discussed by St. Thomas in his Summa Theologiae, but was omitted for lack of space.

The question is raised (as the same author would say) whether humour is in its origins indecent. And at first sight it would appear yes. For the philosopher says that the ludicrous is a division of the disgraceful. And the gods in Homer laugh at the predicament of Ares and Aphrodite in the recital of the bard Demodocus. But on second thoughts it is to be reflected that the song of Demodocus is, by common consent of the critics, a late interpolation in Homer; and the first mention of laughter in the classics is rather the occasion on which the gods laughed to see the lame Hephaestus panting as he limped up and down the hall. Once more, a lame man is funny because he enjoys, like the rest of us, powers of locomotion, but employs them wrong. His gait is incongruous—not unexpectedly so, indeed, for the gods had witnessed this farce daily for centuries; but the gods were children, and the simplest farces always have the best run.

No doubt the psycho-analysts will want us to believe that all humour has its origin in indecency, and, for aught I know, that whenever we laugh we are unconsciously thinking of something obscene. But, in fact, the obscene, as its name implies, is an illegitimate effect of humour. There is nothing incongruous in the existence of sex and the other animal functions; the incongruity lies merely in the fact of mentioning them. It is not human dignity that is infringed in such cases, but a human convention of secrecy. The Stock Exchange joke, like most operations on the Stock Exchange, is essentially artificial; it does not touch the real values of things at all. In all the generalizations which follow it must be understood that the humour of indecency is being left out of account.

Yet there is truth in the philosopher’s assertion that the ludicrous is a division of the disgraceful, in this sense, that in the long run every joke makes a fool, of somebody; it must have, as I say, a human victim. This fact is obscured by the frequency with which jokes, especially modern jokes, are directed against their own authors. The man who makes faces to amuse a child is, objectively, making a fool of himself; and that whole genre of literary humour of which Happy Thoughts, The Diary of a Nobody, and the Eliza books are the best-known examples, depends entirely on the fact that the author is making a fool of himself. In all humour there is loss of dignity somewhere, virtue has gone out of somebody. For there is no inherent humour in things; wherever there is a joke it is Man, the half-angel, the half-beast, who is somehow at the bottom of it. I am insisting upon this point because, on a careless analysis, one might be disposed to imagine that the essence of satire is to be a joke directed against somebody. That definition, clearly, will be inadequate, if our present analysis of humour in general be accepted.

I have said that humour is, for the most part, a modem phenomenon. It would involve a very long argument, and some very far-reaching considerations, if we attempted to prove this thesis of humour as a fact in life. Let us be more modest, and be content for the present to say that the humorous in literature is for the most part a modem phenomenon.

Let us go back to our starting-point, and imagine one pursuing his researches about humming-birds into the Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1797. He skims through a long article on Mr. David Hume, faced by an attractive but wholly unreliable portrait of the hippopotamus. Under “Humming-bird” he will only read the words “See Trochilus.” But immediately following, he will find the greater part of a column under the title “Humour.” Most of it deals with the jargon of a psychology now obsolete, and perhaps fanciful, though not more fanciful, I think, than the psychological jargon of our own day. But at the end he will find some valuable words on humour as it is contrasted with wit. “Wit expresses something that is more designed, concerted, regular, and artificial; humour, something that is more wild, loose, extravagant, and fantastical; something which comes upon a man by fits, which he can neither command nor restrain, and which is not perfectly consistent with true politeness. Humour, it has been said, is often more diverting than wit; yet a man of wit is as much above a man of humour, as a gentleman is above a buffoon; a buffoon, however, will often divert more than a gentleman. The Duke of Buckingham, however, makes humour to be all in all,” and so on.

“Not perfectly consistent with true politeness”—oh, admirable faith of the eighteenth century, even in its decline! “The Duke of Buckingham, however—a significant exception. It seems possible that the reign of the Merry Monarch saw a false dawn of the sense of humour. If so, it was smothered for a full century afterwards by an overpowering incubus of whiggery. The French Revolution had come and gone, and yet humour was for the age of Burke “not perfectly consistent with true politeness.”

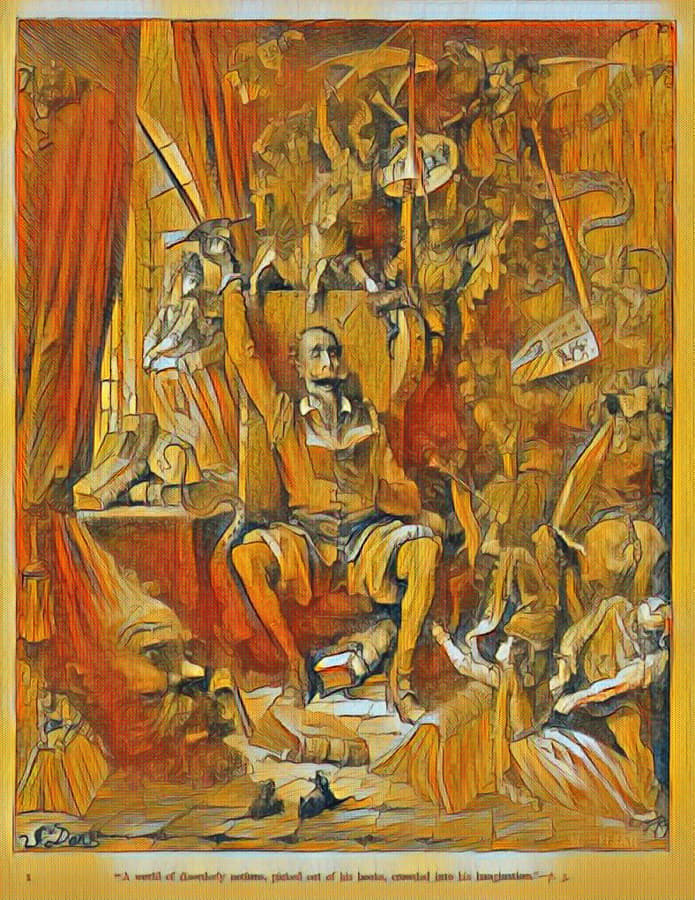

One is tempted, as I say, to maintain that the passing of the eighteenth century is an era in human history altogether, since with the nineteenth century humour, as an attitude towards life, begins. The tone of Disraeli about politics, the tone of Richard Hurrell Froude about all the external part of religion, seems to me quite inconceivable in any earlier age. But let us confine ourselves to literature, and say that humour as a force in literature is struggling towards its birth in Jane Austen, and hardly achieves its full stature till Calverley. I know that there are obvious exceptions. There is humour in Aristophanes and in Petronius; there is humour in Shakespeare, though not as much of it as one would expect; humour in Sterne, too, and in Sheridan. But if you set out to mention the great names of antiquity which are naturally connected with humorous writing, you will find that they are all the names of satirists. Aristophanes in great part, Lucian, Juvenal, Martial, Blessed Thomas More, Cervantes, Rabelais, Butler, Molière, La Fontaine, Swift—humour and satire are, before the nineteenth century, almost interchangeable terms. Humour in art had begun in the eighteenth century, but it had begun with Hogarth! Put a volume by Barrie or Milne into the hands of Edmund Burke—could he have begun to understand it?

You can corroborate the fact of this growth in humour by a complementary fact about our modem age, the decline of naïveté. If you come to think of it, the best laughs you will get out of the old classics are laughs which the author never meant to put there. Of all the ancients, none can be so amusing as Herodotus, but none, surely, had less sense of humour. It is a rare grace, like all the gratiae gratis datae, this humour of the naif. Yet it reaches its climax on the very threshold of the nineteenth century; next to Herodotus, surely, comes James Boswell. Since the dawn of nineteenth century humour, you will find unconscious humour only in bad writers, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, and the rest. Humour kills the naif, nor could any great writer of today recapture, if he would, Boswell’s splendid unselfconsciousness.

Under correction, then, I am maintaining that literature before the nineteenth century has no conscious humour apart from satire. I must now pass on to an impression which all of us have, but an impression so presumptuous that we seldom have the courage to put it into words. It is this, that humour, apart from satire, belongs to the English-speaking peoples alone. I say, the English-speaking peoples, a cumbrous and an unreal division of mankind. But, thank God, you cannot bring any preposterous ethnographical fictions in here. Not even Houston Stewart Chamberlain ever ventured to congratulate the Germans on their sense of humour; not even the Dean of St. Paul’s will dare to tell us that the sense of humour is Nordic. The facts speak for themselves. Satire still flourishes on the Continent; Anatole France was no unworthy citizen of the country of Voltaire. There is satire, too, among the Northern peoples; I believe that if I expressed my private opinion as to who was the world’s greatest satirist I should reply, Hans Andersen. Only in spots, of course; but the man who wrote the Ugly Duckling and the Darning Needle and the Story of the Emperor’s New Clothes seems to me to have a finer sense of the intrinsic ludicrousness of mankind than Swift himself.

Satire is international, as it is of all ages; but where shall humour be found, apart from satire, on the Continent of Europe? Who, unless he were a laugher at the malicious or the obscene, ever picked up the translation of a foreign book in search of a good laugh? Who ever found a good joke in a Continental illustrated paper? Cleverness of drawing abounds, but the captions beneath the drawings are infantile. I have seen a Swedish illustrated supplement, and I do not believe there was a single item in it which would have been accepted by Comic Cuts. I am told that the humorous drama of modem France forms a complete exception to this statement of the facts. I am content to believe it; there must, of course, be exceptions. I put forward the rule as a rule.

Some, no doubt, on a hasty analysis, would limit the field still further by saying that humour is purely English. And it would be easy to defend this contention by pointing to the fact that the English enjoy their joke very largely at the expense of their neighbours. Nothing belongs more decisively to the English-speaking world than the anecdote. We are for ever telling stories, and how many of those stories are about a Scot (we call it a Scotchman), an Irishman, a Jew, or an American? But this, if our definition of humour was a sound one, is in the nature of the case. A foreigner is funny, because he is like ourselves only different. A Scot or an Irishman is funny to the Englishman because he is almost exactly like himself, only slightly different. He talks English as his native tongue, only with an incorrect accent; what could possibly be funnier? A Scot is more funny than a Frenchman just as a monkey is more amusing than a dog; he is nearer the real thing.

But, in fact, all such judgments have been distorted beyond recognition by national hypocrisy. It is the English tradition that the Irish are a nation brimming over with humour, quite incapable of taking anything seriously. Irish people are in the habit of saying things which English people think funny. Irish people do not think them funny in the least. It follows, from the English point of view, that Ireland is a nation of incorrigible humorists, all quite incapable of governing themselves.

The Scot, on the other hand, has an unfortunate habit of governing the English, and the English, out of revenge, have invented the theory that the Scot has no sense of humour. The Scot cannot have any sense of humour, because he is very careful about money, and drinks whisky where ordinary people drink beer. All the stories told against the Scottish nation are, I am told, invented in Aberdeen, and I partly believe it. There is (if a denationalized Ulsterman like myself may make the criticism) a pawkiness about all the stories against Scotland which betrays their Caledonian origin. The fact is that the Scottish sense of humour differs slightly from the English sense of humour, but I am afraid I have no time to indicate the difference. There is humour in the country of Stevenson and Barrie; and if the joke is often against Scotland, what better proof could there be that it is humour, and not satire?

Whatever may be said of Americans in real life, it is certain that their literature has humour. Personally I do not think that the Americans are nearly as proud as they ought to be of this fact; Mark Twain ought to be to the American what Bums is to the Scot, and rather more. The hall-mark of American humour is its pose of illiteracy. All the American humorists spend their time making jokes against themselves. Artemus Ward pretended that he was unable even to spell. Mark Twain pretended that he had received no education beyond spelling, and most of his best remarks are based on this affectation of ignorance. “What is your bête noire?” asked the revelations-of-character book, and Mark Twain replied, “What is my which?” “He spelt it Vinci, but pronounced it Vinchy; foreigners always spell better than they pronounce”—that is perhaps one of the greatest jokes of literature, but the whole point of it lies in a man pretending to be worse educated than he really is.

Mr. Leacock, as a rule, amuses by laughing at himself. America, on the other hand, has very little to show in the way of satire. Lowell was satirical, in a rather heavy vein, and Mr. Leacock is satirical occasionally, in a way that seems to me purely English. I want to allude to that later on; for the present let it be enough to note that the Americans, like the English and the Scots, do possess a literary tradition of non-satirical humour.

Thus far, we have concluded that the humorous in literature is the preserve of that period which succeeds the French Revolution, and of those peoples which speak the English language under its several denominations; unless by the word humour you understand “satire.”

It is high time, obviously, that we attempted some definition of what ‘satire is, or at least of the marks by which it can be distinguished from non-satirical humour. It is clear from the outset that the author who laughs at himself, unless the self is a deliberately assumed one, is not writing satire. Happy Thoughts and The Diary of a Nobody may be what you will; they are not satire. The Tramp Abroad is not satire; My Lady Nicotine is not satire. For in all these instances the author, with a charity worthy of the Saints—and indeed, St. Philip Neri’s life is full of this kind of charity—makes a present of himself to his reader as a laughingstock.

In satire, on the contrary, the writer always leaves it to be assumed that he himself is immune from all the follies and the foibles which he pillories. To take an obvious instance, Dickens is no satirist when he introduces you to Mr. Winkle, because there is not the smallest reason to suppose that Dickens would have handled a gun better than Mr. Winkle. But when Dickens introduces you to Mr. Bumble he is a satirist at once, for it is perfectly obvious that Dickens would have handled a porridge-ladle better than Mr. Bumble did. The humorist runs with the hare; the satirist hunts with the hounds.

There is, indeed, less contempt in satire than in irony. Irony is content to describe men exactly as they are, to accept them professedly, at their own valuation, and then to laugh up its sleeve. It falls outside the limits of humorous literature altogether; there is Irony in Plato, there is irony in the Gospels; Mr. Galsworthy is an ironist, but few people have ever laughed over Mr. Galsworthy.

Satire, on the contrary, borrows its weapons from the humorist; the satirized figure must be made to leap through the hoops of improbable adventure and farcical situation. It is all the difference between The Egoist and Don Quixote. Yet the laughter which satire provokes has malice in it always; we want to dissociate ourselves from the victim ; to let the lash that curls round him leave our withers unwrung. It is not so with humour: not so (for instance) with the work of an author who should have been mentioned earlier, Mr. P. G. Woodhouse. To read the adventures of Bertie Wooster as if they were a satire on Bertie Wooster, or even on the class to which Bertie Wooster may be supposed to belong, is to misread them in a degree hardly possible to a German critic. The reader must make himself into Bertie Wooster in order to enjoy his Jeeves, just as he must make himself into Eliza’s husband in order to enjoy his Eliza. Nobody can appreciate the crackers of humour unless he is content to put on his fool’s cap with the rest of the party.

What, then, is the relation between humour and satire? Which is the parent, and which the child? Which is the normal organ, and which the morbid growth? I said just now that satire borrows its weapons from the humorist, and that is certainly the account most of us would be prepared to give of the matter off-hand. Most things in life, we reflect, have their comic side as well as their serious side; and the good-humoured man is he who is content to see the humorous side of things even when the joke is against himself. The comic author, by persistently abstracting from the serious side of things, contrives to build up a world of his own, whose figures are all grotesques, whose adventures are the happy adventures of farce. Men fight, but only with foils; men suffer, but only suffer indignities; it is all a pleasant nursery tale, a relief to be able to turn to it when your mind is jaded with the sour facts of real life. Such, we fancy, is the true province of the Comic Muse; and satire is an abuse of the function.

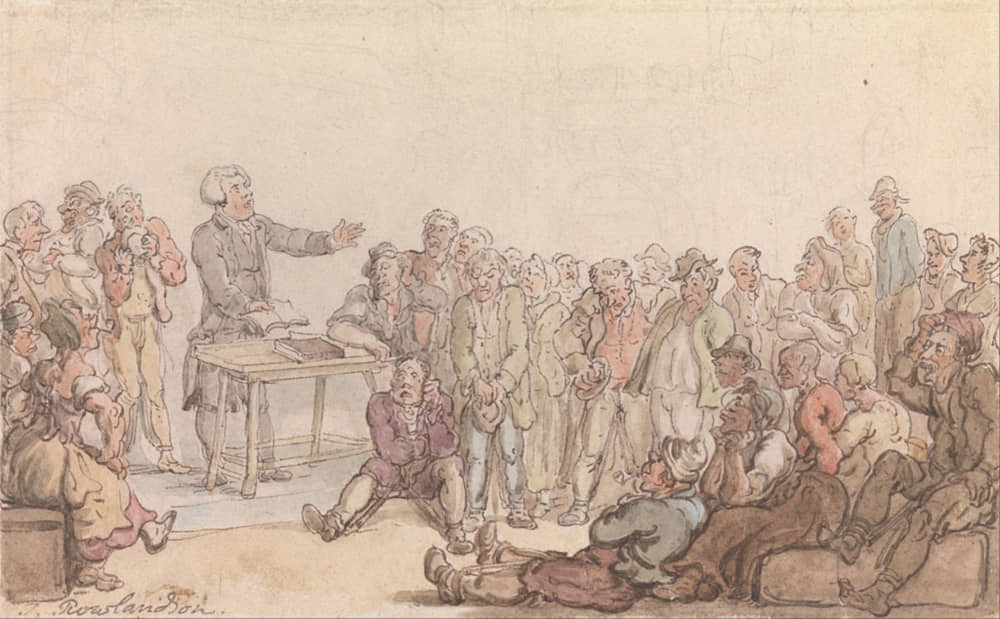

The satirist is like one who should steal his little boy’s water-pistol and load it with vitriol, and so walk abroad flourishing it in men’s faces. A treacherous fellow, your satirist. He will beguile the leisure of an Athenian audience, needing some rest, Heaven knows, from the myriad problems of a relentless war with powerful neighbours, by putting on a little play called The Birds. Capital; we shall enjoy that. Two citizens of Athens, so the plot runs, take wings to themselves and set out to build a bird city, remote from the daily instance of this subnubilar world. Excellent! That is just what we wanted, a relief for tired brains! And then, the fellow has tricked us, it proves, after all! His city in the clouds is, after all, only a parody of an Athenian colony, and the ceremonies which attend its inauguration are a burlesque, in the worst possible taste, of Athenian colonial policy. We came here for a holiday, and we are being treated to a sermon instead! No wonder the Athenian audiences often refused the first prize to Aristophanes.

Skip twenty-one centuries, and find yourself in the times of the early Georges. There has been a great vogue, of late, for descriptions of travel in strange countries; and now (they are saying in the coffee-houses) the Dean of St. Patrick’s, Dublin, has written a burlesque of these travel narratives, about countries that never existed at ail—the ingenious dog! And then, as we read, it dawns upon us suddenly that Lilliput and Brobdingnag are not, after all, so distant, so imaginary; in fact, we have never really got away from the England of the Georges at all. The spirit of satire has overlooked us, like a wicked fairy, and turned the milk of human kindness sour as we churned it.

My present thesis, not dogmatically asserted but rather thrown out as if for discussion, is that this way of viewing the relations between humour and satire is a perversion of history. To think of satire as a particular direction which humour may happen to take, a particular channel into which humour may be diverted, is to neglect, surely, the broad facts as we have stated them above. Humour is of an age, satire of all ages; humour is of one particular civilization, satire of all countries. Is it not, then, more reasonable to suppose that satire is a normal function of the human genius, and humour that has no satire in it a perversion of the function, a growth away from the normal? That our sense of the ridiculous is not, in its original application, a child’s toy at all, but a weapon, deadly in its efficacy, entrusted to us for exposing the shams and hypocrisies of the world? The tyrant may arm himself in triple mail, may surround himself with bodyguards, may sow his kingdom with a hedge of spies, so that free speech is crushed and criticism muzzled. Nay, worse, he may so debauch the consciences of his subjects with false history and with sophistical argument that they come to believe him the thing he gives himself out for, a creature half-divine, a heaven-sent deliverer. One thing there is that he still fears; one anxiety still bids him turn this way and that to scan the faces of his slaves. He is afraid of laughter. The satirist stands there, like the little child in the procession when the Emperor walked through the capital in his famous new clothes; his is the tiny voice that interprets the consciousness of a thousand onlookers: “But, Mother, he has no clothes on at all!”

Satire has a wider scope, too. It is born to scourge the persistent and ever-recurrent follies of the human creature as such. And, for anybody who has the humility to realize that it is aimed at him, and not merely at his neighbours, satire has an intensely remedial effect; it purifies the spiritual system of man as nothing else that is human can possibly do. Thus, every young man who is in love should certainly read The Egoist (there would be far less unhappiness in marriage if they all did), and no schoolmaster should ever begin the scholastic year without re-reading Mr. Bradby’s Lanchester Tradition, to remind him that he is but dust.

Satire is thus an excellent discipline for the satirized: whether it is a good thing for the satirist is more open to question. Facit indignatio versum; it is seldom that the impetus to write satire comes to a man except as the result of a disappointment. Since disappointment so often springs from love, it is not to be wondered at that satirists have ever dealt unkindly with woman, from the days of Simonides of Amorgos, who compared woman with more than thirty different kinds of animals, in every case to her disadvantage. A pinched, warped fellow, as a rule, your satirist. It is misery that drives men to laughter. It is bad humour that encourages men first to be humorous. And it is, I think, when good-humoured men pick up this weapon of laughter, and, having no vendettas to work off with it, begin tossing it idly at a mark, that humour without satire takes its origin.

In a word, humour without satire is, strictly speaking, a perversion, the misuse of a sense. Laughter is a deadly explosive which was meant to be wrapped up in the cartridge of satire, and so, aimed unerringly at its appointed target, deal its salutary wound humour without satire is a flash in the pan; it may be pretty to look at, but it is, in truth, a waste of ammunition. Or, if you will, humour is satire that has run to seed; trained no longer by an artificial process, it has lost the virility of its stock. It is port from the wood, without the depth and mystery of its vintage rivals. It is a burning-glass that has lost its focus; a passenger, pulling no weight in the up-stream journey of life; meat that has had the vitamins boiled out of it; a clock without hands. The humorist, in short, is a satirist out of a job; he does not fit into the scheme of things; the world passes him by.

The pure humorist is a man without a message. He can preach no gospel, unless it be the gospel that nothing matters; and that in itself is a foolish theme, for if nothing matters, what does it matter whether it matters or not? Mr. Wodehouse is an instance in point, Mr. Leacock nearly so, though there is a story in Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich about the amalgamation of two religious bodies on strictly commercial lines, which comes very close to pure satire. Barry Pain is a humorist who is seldom at his best when he attempts satire; the same fate dogged Mark Twain, though I think he would have liked to be a satirist. Mr. A. A. Milne is in a similar case, and so indeed are all the modem Punch writers by the terms (you might say) of their contract. No contrast is more surprising than the contrast in atmosphere between the letterpress of Punch before 1890 and its letterpress since. The old Punches are full of very bad satire; there is hardly anything else in them; it is all on the same sort of level as John Bull in its Bottomley days—anti-aristocratic, and-foreign, and-clerical, very much like some rag of the Boulevards. Today, it is the home of superbly finished humour—humour cultivated as a fine art. But satire is absent.

Some of the greatest humorists have halted between two destinies, and as a rule have been lost to satire. Sir W. S. Gilbert, a rather unsuccessful satirist in his early days, inherited the dilemma from his master, Aristophanes. Patience is supreme satire, and there is satire in all the operas; but in their general effect they do not tell: the author has given up to mankind what was meant for a party. Mr. Chesterton is in the same difficulty; he is like Johnson’s friend who tried to be a philosopher, but cheerfulness would keep on coming in. The net effect of his works is serious, as it is meant to be, but his fairy-like imagination is for ever defeating its own object in matters of detail. But indeed, Mr. Chesterton is beyond our present scope; for he is rash enough to combine humour not merely with satire but with serious writing ; and that, it is well known, is a thing the public will not stand.

A few modem authors have succeeded, in spite of our latter-day demand for pure humour, in being satirists first and last: Samuel Butler of Erewhon, and W. H. Mallock, and Mr. Belloc, I think, in his political novels. The very poor reception given to these last by the public proves that there is more vinegar in them than oil.

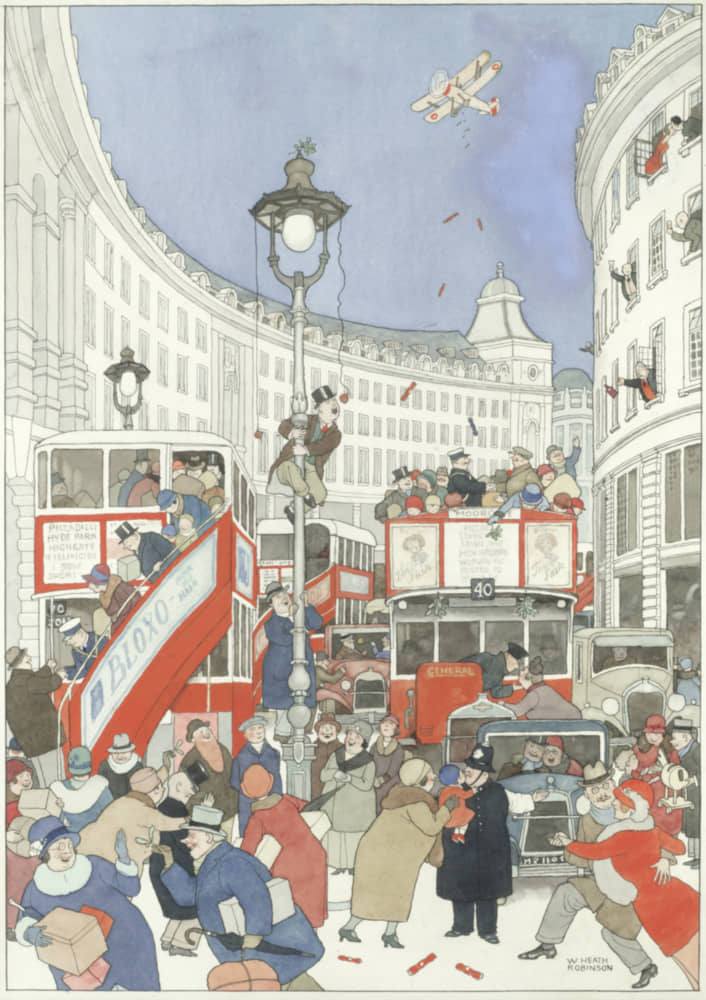

Humour, if we may adopt for a moment the loathsome phraseology of journalism, has “come to stay.” It is, if our analysis be true, a byproduct and in a sense a waste-product; that does not mean that it has no significance. A pearl is a by-product, and from the fishmonger’s point of view a waste-product; but it has value so long as people want it. And there is at present a public demand for humour which implies that humour should take its place among the arts, an art for the art’s sake, not depending on any fruits of practical utility for its estimation. There is art in O. Henry, though he does not scourge our vices like Juvenal; there is art in Heath Robinson, though he does not purge our consciences like Hogarth.

What rank humour is to take as compared with serious writing is, perhaps, an unanswerable problem; our histories of nineteenth century literature have not yet been bold enough to tackle it. It is probable, I think, that humour is relatively ephemeral; by force of words humour means caprice, and the caprice of yesterday is apt to leave us cold. There is a generation not yet quite dead which says that nothing was ever so funny as the Bongaultier Ballads. The popularity of the Ingoldsby Legends is now, to say the least, precarious; and I doubt if the modem youth smacks its lips as we did over the Bab Ballads themselves. Read a book of A. A. Milne’s, and then turn to an old volume of Voces Populi, and you will realize that even in our memory humour has progressed and become rarefied.

What reputations will be left unassailable when the tide has receded, it would be rash to prophesy. For myself, I like to believe that one name will be immortal at least, that of Mr. Max Beerbohm. Incomparably equipped for satire, as his cartoons and his parodies show, he has yet preferred in most of his work to give rein to a gloriously fantastic imagination, a humorist in satirist’s clothing. One is tempted to say with the prophet: May I die the death of the righteous, and may my last end be like his!

Meanwhile, a pertinent question may be raised. What will be the effect of all this modem vogue for pure humour upon the prospects of satiric writing? We are in danger, it seems to me, of debauching our sense of the ridiculous to such an extent as to leave no room for the disciplinary effect of satire. I remember seeing Mr. Shaw’s Press Cuttings first produced in Manchester. I remember a remark, in answer to the objection that women ought not to vote because they do not fight, that a woman risks her life every time a man is born, being received (in Manchester!) with shouts of happy laughter. In that laughter I read the tragedy of Mr. Bernard Shaw. He lashes us with virulent abuse, and we find it exquisitely amusing. Other ages have stoned the prophets; ours pelts them instead with the cauliflower bouquets of the heavy comedian.

No country, I suppose, has greater need of a satirist today than the United States of America; no country has a greater output of humour, good and bad, which is wholly devoid of any satirical quality. If a great American satirist should arise, would his voice be heard among the hearty guffaws which are dismally and eternally provoked by Mutt, Jeff, Felix, and other kindred abominations? And have we, on this side of the Atlantic, any organ in which pure satire could find a natural home?

I believe the danger which I am indicating to be a perfectly real one, however fantastic it may sound—the danger, I mean, that we have lost, or are losing, the power to take ridicule seriously. That our habituation to humorous reading has inoculated our systems against the beneficent poison of satire. Unhappy the Juvenal whom Rome greets with amusement; unhappier still the Rome, that can be amused by a Juvenal

I am not sure, in reading through this essay again, that there is any truth in its suggestions. But I do not see that there can be any harm in having said what I thought, even if I am no longer certain that I think it.

Featured image: “Satire on Tulip Mania,” by Jan Brueghel, ca. 1640.