Once again, the brilliant minds at University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, better known as OISE, has graced the world with another one of their hair-brained theories. It’s called Indigenous Ways of Knowing and it’s coming to schools near you.

OISE is rallying teachers to poison our children with these ludicrously pre– non-historical ways of thought.

CLICK HERE to be forwarded to the module on OISE’s website designed to educate teachers on what is and how to teach Indigenous Ways of Knowing.

What exactly is Indigenous Ways of Knowing? Well, buckle up because for anybody with half a brain it’s going to be a bumpy ride as we dive into the seven topics of this half-witted module.

TOPIC ONE “What is Indigenous Knowledge?”

So, what exactly is Indigenous Knowledge? Your guess seems to be as good as anybody else’s. Our mis-informed friends at OISE don’t even define what they’re talking about. Like many of the buzzwords taught at our universities, they’re about triggering certain emotions as opposed to thoughts.

To quote the module, “In this module, Indigenous knowledge is described rather than defined. There are sources and characteristics that are shared among diverse Indigenous peoples but a hesitance to define it in one limiting way.”

No worries, let’s just cut them some slack and carry on with the module. But wait! What is the reason they give for not being able to describe what they are talking about? Oh right…. it’s because of those rotten Westerners….

According to the module, “Indigenous knowledge definitions can be problematic because they often use the dominant knowledge system (Western knowledge) as a frame of reference.”

See what I mean about triggering emotions instead of thoughts? They even blame the West for not being able to articulate their own thoughts. Is Western guilt hitting rock bottom? Or is it as the Irish say, “if you think you’ve hit rock bottom, wait a while and you’ll hear a knock from bellow.”

Then, they quote Dr. Marie Battiste‘s description of Indigenous knowledge. She claims that “Indigenous knowledge compromises the complex set of technologies developed and sustained by Indigenous civilizations. Often oral and symbolic, it is transmitted through the structure of Indigenous languages and passes on to the next generation through modeling, practice, and animation, rather than through written word.”

The module then states “Indigenous knowledge is embedded in community practices, rituals, and relationships. As a living knowledge, it is holistic, contextual, and relational.”

In other words, Indigenous knowledge is comprised of stone aged tools, pre-historic oral traditions, and rituals.

TOPIC TWO “Characteristics of Indigenous Knowing”

Finally, it’s time to dive into the descriptions given about the characteristics of Indigenous knowing. The characteristics of indigenous knowing are that it is “personal, orally transmitted, experiential, holistic, and narrative.”

What do these folks mean when they say that Indigenous knowledge is personal?

They mean “no one person has the truth… With multiple perceptions at the core, indigenous knowledge actualizes itself in context….thus indigenous knowledge is highly dynamic.”

Translation: more of that Post-modern garbage juice which claims that there is no real truth and that “everything’s, like, your, like, opinion man.”

If there’s no “real” truth, and everybody knows just as much as everybody else, then why are we paying you to teach us this garbage? If the students know as much as the teacher, why should they show up to class (or take the time to study this absurd module)?

What do these folks mean when they say that Indigenous Ways of Knowing is orally transmitted?

To quote the module, “Oral tradition is not a precursor to literate traditions. They are simply different ways of knowledge keeping.”

I think that they might have put the wrong herb in the peace pipe on this one. Oral tradition is not a precursor to literate tradition? What are they talking about?!

Do they even know what history, the study of written records, means? Or what pre-historic societies are? Do they not understand that people spoke to each other before they invented script and started to write things down?

I feel obliged to remind you that these people are the teachers of your children’s teachers!

What do these folks mean when they say that “Indigenous Ways of Knowing” are experiential?

Well, the module claims, “The land is alive, the only way to know that is to be on the land. The senses can know more deeply and concretely than knowledge gained though reading or being told.”

I’m not going to lie, there is some truth in that claim. One only has to read a bit of Walt Whitman to sympathize with this position. But that being said, I severely question how deeply one can understand a blade of grass just by holding it, as opposed to learning about it in a botany text book. Furthermore, it is very questionable that holding it, seeing, and tasting it provides a “deeper” understanding.

What do these folks mean when they say that “Indigenous Ways of Knowing” are holistic?

The module defines Indigenous knowledge as holistic because it “brings together internal and external worlds, the physical and the spiritual.”

Hold up….

Last time I checked, The Canadian Public School Board was a secular board. Then why are we telling teachers to introduce Native Spirituality into the classroom? Isn’t the entire idea of secularism the right to be free of religious rule and religious teaching?

Is telling teachers to teach Native Spirituality fair to other spiritual denominations?

For example, The Orthodox Church of America claims to be holistic. Orthodox also believe their teachings are universal and unite the external and internal parts of ourselves. As strict monists, they believe in the existence of only one world (that the natural and supernatural are united as one in the same world).

Ironically, the OCA also has a disproportionately high number of aboriginals, particularly the Alaskan Kodiak naitives, in the hierarchy of their church.

Should teachers be allowed, or rather encouraged, to bring in American Orthodox priests to teach their children about the “wonders of creation” and the “Orthodox Ways of Knowing?”

If Indigenous Ways of Knowing are spiritual, then like other spiritual teachings it doesn’t belong in a secular classroom.

If Buddhists and Orthodox Christians have to leave lessons about their incense usage at home, Indigenous Ways of knowing should leave stories about the “sacred prayers” of the peace pipe at home as well.

What do these folks mean when they say Indigenous Ways of Knowing is narrative?

They claim that “Indigenous knowledge is conveyed using a narrative. Stories contain the knowledge that is needed to live in a good way. Transmitting vital teachings without preaching.”

That sounds like it’s OK, until you start to actually think about it. Hate to break to these guys, but telling moral stories is one of the oldest forms of preaching. It’s what that Jesus guy was doing when he spoke in parables.

All this shows is that they want to preach to children in everything but name.

TOPIC THREE “Sources of Indigenous Knowledge”

The module lists “1. Traditional knowledge, 2. Empirical Knowledge, 3. Revealed knowledge” as the sources of Indigenous knowledge.

First off, how do we know that what the Indigenous think is “traditional knowledge” actually is what the Indigenous pre-European contact actually believed?

If everything is passed down from word of mouth, then how do we know that pre-European-contact-indigenous groups actually believed the stories that we currently claim are “traditional” native stories? Isn’t it possible that some of these stories are post-contact historical retro-projections?

Second, they’re misusing the word “Empirical.” Empiricism is an epistemological philosophy invented by Europeans invented in the 17th and 18th century.

If all they mean by “Empirical Knowledge” is that the Indigenous saw, felt, smelt, heard, and tasted things then whop-tie-do. There’s nothing special about that.

Welcome to the human condition. It certainly doesn’t make the indigenous way of knowing anymore distinct from anybody else’s way of knowing.

Third, how are we going to teach our children the Indigenous Way of Knowing if it comes to us in dreams and revelations?

The module defines “Revealed Knowledge” as “dreams, visions, and intuitions.” all of which are un-teachable.

What happened to citations? Verifiable and falsifiable hypotheses? The scientific method? Can teachers consider knowledge credible simply because it came to them in a dream?

TOPIC FOUR “Indigenous Axiology, Values, and Ethics “

In this part of the module, the focus is on the values and ethics within Indigenous Ways of Knowing.

There is nothing here that Ancient Greek Virtue philosophers didn’t already propose. Above all else, at least when the ancient Greeks spoke about ethics, they could write their thoughts down and have future generations check their notes.

This way each generation wasn’t working from scratch and from the time torn tatters of broken miscommunications found in all oral traditions.

After all, to quote the module, “the way one one comes to know is as important as what one comes to know.”

TOPIC FIVE “Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science Side by Side”

Here comes the fun part.

The module is actually putting this Indigenous Ways of Knowing nonsense on par with Western Science.

The module starts by denouncing science as nothing more than a Eurocentric and Imperialist tool to push aside the ideas of other cultures.

“The modern Western World developed in tandem with the expansion of European colonial empires. With colonial imperialism came an emphasis on the centrality and superiority of European theories and ideas also known as Eurocentrism. Eurocentrism has used Western science to discredit and delegitimize and marginalize Indigenous knowledges … This process has also been described as Cognitive imperialism (Battiste, 1986)”

Let us concede that Europeans turned to tribal peoples and spoke out against superstition, regional folk lore, and mislead mysticism. Is that really so bad?

Let us further concede that Europeans were even quick to push aside useful knowledge possessed by the natives because of pompous and ignorant racism. Does that mean that suddenly the epistemology of Western Science is on par with Indigenous Ways of Knowing?

Is all epistemology, all ways of knowing things, equal? Of course not.

If not, how does Indigenous Ways of Knowing compare with Western Science. Luckily for us, the module measures them both against one another in a Venn diagram.

^Cited from the geniuses at OISE^

The module explains how the Venn diagram presents “characteristics of both systems side by side to illustrate the different emphases, assumptions and outcomes of knowing within each system.”

Notice how they didn’t put “holistic” in the middle. Are they claiming that Western science, which studies the universal laws that permeate everything from to quarks and galaxies, is not holistic? Do they even know what Western Science is?

Apparently not, considering how they put “practical experimentation” as exclusively indigenous. It’s not like Western Science conducts any practical experimentation … Oh wait! It does! That’s what laboratories are for!

Who do they think comes up with the vaccines, generates new space aged materials, and increases agricultural yields?!

I’m just glad that they recognized that Western Science, and not Traditional Naive Knowledge, possess “global verification; hypothesis falsification; quantitative written records; communication of procedures, evidence, and theory; mathematical models;” and most importantly “skepticism” because God knows belief in Indigenous Knowledge requires blind faith.

The fact that they didn’t put “limited to evidence and explanation within the physical world” in middle just goes to show that “Traditional Native Knowledge” is just more religious neo-paganism.

Does this belong in a secular school system?

TOPIC 6 & 7 “Indigenous Knowledge and Learning, Re-imagining Education” & “Suggested Activities”

In these parts of the module, they argue that educators should “Re-imagine Education” and conduct activities with their students on “Indigenous Ways of Knowing.”

This includes sharing “with your fellow learners this living representation of First Nations Holistic Life Long Learning model Created by the Canada Council on Learning and the Aboriginal Learning Centre.”

Remember that this module is designed for the teachers of your children.

Is anybody considering home school?

DISCLAIMER

The module, like any faulty product, comes with a disclaimer.

It states, “Remember that the boundaries between the two are not so hard and fast and that both kinds of knowledge can exhibit different aspects. Most importantly, there are instances where indigenous knowledge and Western Science overlap.”

Personally, I completely agree. But insomuch as they define describe what Indigenous Ways of Knowledge is in contrast to Western Science, the more I feel like I need chemotherapy to get rid of this mental cancer.

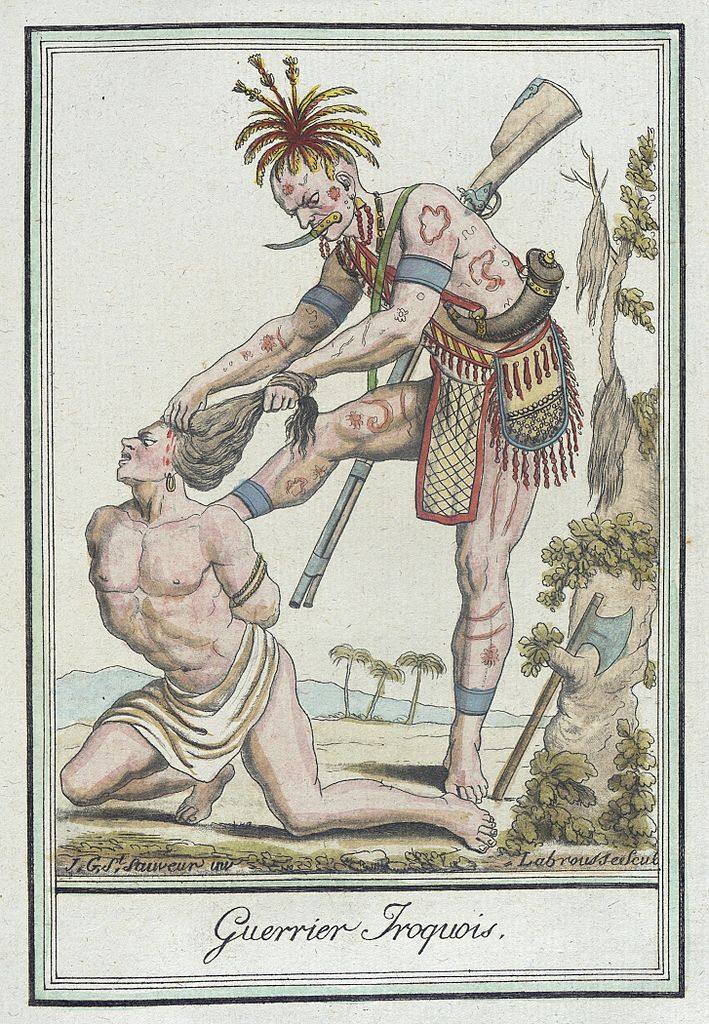

The photo shows, “Le guerrier Iroquois,” by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, hand-tinted etching, done in 1797.