Although it is puerile to try to predict the long-term effects of the Russian military operation in Ukraine, it seems reasonable to presume that we are at the doorstep of a different reality, which will transform international politics to extremes that we can barely intuit, but from which we cannot exclude an “every man for himself” in Europe, as soon as the shock waves of war reach the voter’s pocketbook.

All in all, the lack of unity of Western societies, and the disorientation and lack of purpose conveyed by their leaders contrast with the will to power and international affirmation shown by the new international players, so that, even if we are able to avoid a warlike conflagration that could well be the last, it makes it very difficult to shake off the suspicion that we are crossing the threshold of a new era, which is the second death of the world of yesterday.

Few things symbolized that world better than the dominance of the US dollar, which even in these days of change more than a currency, continues to be the axis around which US commercial, security and cultural affairs revolve at the global level, to the point that there has been a direct cardinality between the financial and military leadership of America at the global level over the last 100 years, but especially since the time of Richard Nixon’s presidency.

In order to understand this better, and at the same time to understand the incentives of the emerging powers to undermine this monetary hegemony, it is necessary to review the chronology that has led to the US dollar having a dominant role in the world economy, for which it is necessary to go back to the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system, agreed upon by the Allies, shortly before the end of the Second World War, whereby most Western and assimilated economies fixed their exchange rates to the value of the US dollar, whose value was backed by its parity with US gold reserves, thus putting an end to the Gold Standard, which had been in force since the 19th century, more or less as conceived by David Hume in 1752.

The Bretton Woods system was a transitional formula to allow a certain degree of financial openness at world level, providing greater accessibility and exchange rate certainty to the foreign exchange market, dominated by the large international banks. However, at the beginning of the 1970s, the system showed its limitations because of the fact that the economic expansion of the incipient globalization demanded more dollars than the US gold reserves could support.

Faced with this situation, the Smithsonian Agreement was put in place, under the umbrella of the OECD, creating a system in which currencies could operate freely, floating within a 2% tolerance margin, both up and down. In other words, the widespread adoption of fiat money took place, i.e., backed by faith in the stability and strength of the economy of the issuing bank’s country.

For decades, and by far the only one with the depth and liquidity of its capital markets, supported by the robustness of its political institutions and its economic weight, the US dollar became the safe haven currency for all purposes, which led to the enormous US capacity to finance itself through the placement of sovereign bonds—or, in other words, to borrow in a currency whose issue and exchange rate it controls: the US finances its astronomical deficit thanks to the demand for dollars by other countries—in which third countries deposit part of their foreign investment and the central banks their foreign exchange reserves. The US finances its astronomical deficit thanks to the demand for dollars by other countries, in which third countries deposit part of their foreign investment and central banks their foreign exchange reserves. No other nation has this capacity, which enables the US to use financial sanctions (e.g., seizure of dollar-denominated financial assets) against other states asymmetrically, i.e., without the slightest possibility of the affected country responding reciprocally to the punitive measures inflicted on it. Similarly, the United States has at its disposal tools such as the Foreign Assets Control Act of the Treasury Office, with which it imposes sanctions on individuals and legal entities that are not under US jurisdiction, something which, at the very least, calls into consideration questions of legitimacy, sovereignty and legal security.

These sanctions have a scope that goes beyond the mere direct damage caused to the sanctioned party, since their effect extends indirectly as a consequence of the reluctance of third parties to do business with sanctioned entities and countries for fear of being sanctioned or hindered in turn when dealing with US financial entities, which makes the US dollar a powerful instrument of international economic coercion. It is not surprising then that the emerging powers of the new order in the making are struggling to mitigate the US ability to use its monetary muscle as an instrument of foreign policy.

After all, the dominance of the US dollar as a reserve currency is ultimately more a symptom than a cause, since if the central banks of third countries had fewer US dollar assets, the differences in the exchange rate or interest rates of the US dollar would be marginal. Nevertheless, the percentage of national reserves in US dollars and their preponderance in foreign exchange trade has hardly shown any signs of erosion, despite the emergence of the euro and the substantial growth of China in this century, even in spite of the exorbitant US current account and fiscal deficit already mentioned, so that the coercive capacity of the US currency remains intact.

Although attempts by other economic powers to rid themselves of this sword of Damocles have yielded modest results to date (e.g., the creation by France, Germany and the United Kingdom of INSTEX, an alternative to SWIFT, the American electronic banking system; the launch by China of the Shanghai hydrocarbon futures market, the redenomination in euros of the intergovernmental contracts of the partners of the European Union, or the aforementioned purchase and sale agreement without dollars between Russia and India), the realities of the new polycentric world scenario make it inevitable that the relative weight of each of the emerging blocs will achieve strategic autonomy in the financial arena, so that a sustained increase in multilateral efforts to erode the hegemony of the US dollar, and with it, the monopoly of unarmed coercion, is to be expected. All this, in short, will be the epitaph of the prosperity that liberal democracies enjoyed since the end of World War II, being the fruit of the analysis carried out by Western political elites in the face of the communist threat, which concluded that the main threat to liberal democracy was unemployment.

This led to the promotion of common policies orchestrated to keep unemployment levels below 5%. In practice, this meant virtually full employment and a providential welfare state capable of combining Keynesian policies with the beneficial inclusion in the system of the remaining five percent of the population that could not be integrated into the labor market. And it is here that internal contradictions begin to develop.

As argued by Michał Kalecki in the 1940s, once a situation of full employment is reached, the incentives for workers to stay in the same job are drastically reduced, forcing the recruitment and retention of employees to be incentivized through wage increases.

This, in turn, leads companies to raise the prices of their products and services. In other words, creating inflation and contracting debt in order to grow. This is precisely the dynamic into which the advanced democracies entered—the higher the levels of employment, the higher the levels of inflation. This was evident in the 1950s and 1960s, a period in which a scenario was reached in which inequality levels were at historic lows, thanks to the containment of corporate profits and the cushioning of the burden of debt through inflation.

Of course, this induced inflation actually meant a tax on the returns of investors and lenders who saw their returns restricted and thus diminished. To all this, both companies and financial institutions reacted by promoting a new economic paradigm in which full employment took a back seat to the benefit of price stability, which inevitably led to the induction of unemployment as a corrective measure to the inflationary dynamics described above.

This led to strict wage control, resulting in the dominance of a creditor’s market, creating the fiction of inflationary stagnation, coupled with investment-stimulated, debt-based productivity growth that in real terms only benefited the providers of capital. Of course, this model was not sustainable, and so the 2008 crisis forced central banks to turn the printing presses on full blast to inject paper money into an economy that once again suffered from internal contradictions, accentuated by a lack of monetary liquidity. Once again, returns on capital were at rock bottom, but this time due to deflation caused by virtually negative interest rates, placing working people in an unsustainable situation in the face of a precarious and volatile labor market, disproportionate levels of incremental indebtedness and systemic wage restraint.

All this brings us to 2017, a time when citizens inadvertently discovered the power that the vote gives them to kick monetarism in the shin of liberal democracy, a symptom of the disaffection of large sectors of the working population, which suffers from a limited formal education and resents the effects of globalization on their way of life at work, forcing them into a de facto alienation that is easily exploited by populist movements which pick up on the loss of social dignity and respect that is perceived by those who do not benefit from globalization. For several decades, there was the illusion that such frameworks as Giddens’ Third Way could achieve a political equilibrium based on a mixed economy, and thus take the initiative to overcome the crisis into which Western social democracy was plunged by the implosion of the Soviet bloc.

In practice, this attempt ended up being the West’s swan song, embodied by Clinton and Blair’s devil’s bargain with the capital markets and financial products, such as subprime mortgages that catalyzed the collapse of the banking system in 2007, and served to incubate the popular response that emerged from the ideological collapse of the social democratic parties that should have known how to contain the desperation of the victims of the crisis by channeling, in a positive way, the disaffection with a system that they no longer found relevant beyond a welfare function that tends to paternalism and manipulation, thus eroding the dignity of workers who abhor not being useful to society. These social sectors end up, in the absence of suggestive alternatives, withdrawing from the labor market and from social life in general, subsisting on public aid that only succeeds in cementing their conviction of being a burden on a society that does without them. Few tears will be shed at the funeral of the American dollar.

Santiago Mondejar Flores is a consultant, lecturer and columnist on geopolitics and international political economy. This article appears courtesy of Posmodernia.

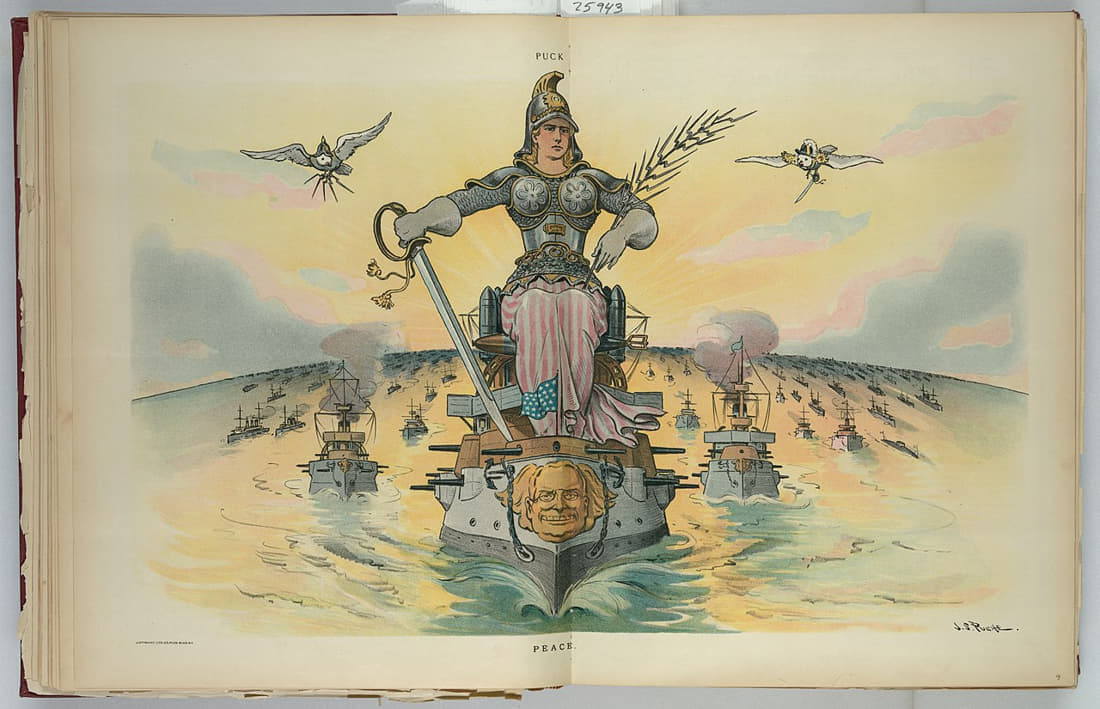

Featured: Peace, by J.S. Pughe, illustration published in Puck, v. 57, no. 1465 (March 29, 1905).