We are very pleased to provide this excerpt from Fulvio di Blasi’s forthcoming book, Vaccination as an Act of Love? which appears through the kind courtesy of Phronesis Editore.

The advent of the so-called “anti-Covid vaccines” was marked by the largest institutional fraud in history, to the detriment of informed consent: a fraud made easier and more disturbing by the power that finance and politics wield today in the world of global communication.

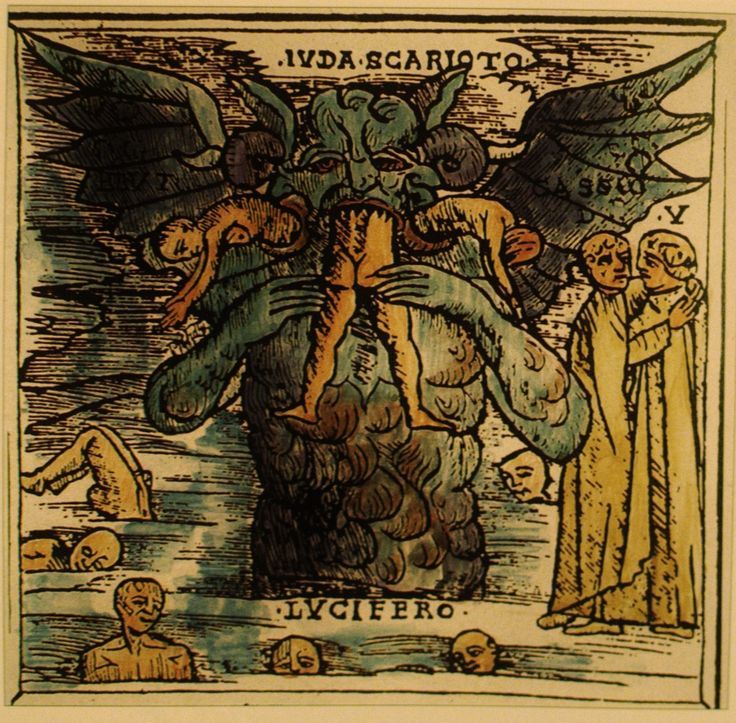

This fraud triggered a time of unprecedented violence, hatred, and persecution against all those who expressed doubts, sought the truth, and never tired of defending their freedom. The schizophrenic and almost demonic paradox of this campaign of hatred and violence is that it was carried out under the banner of terms, such as “love” or “civic duty,” now devoid of any meaning other than the demagogic use (typical of totalitarian systems) of the terminology of good to carry out evil policies. Transforming good into evil and evil into good is the most the Devil could wish for; it is his greater enjoyment. For those who believe, it is easy to see the Devil’s hand in these times.

Vaccination as an Act of Love? retraces the foundations of the analysis of the moral act to rediscover what it means to do good or evil, both in the Christian tradition and in that of Western thought. The ethical choice presupposes adequate knowledge of all the relevant factors of the action.

Fulvio Di Blasi is a practicing lawyer who holds a Ph.D. in the philosophy of law. He is an expert especially in Aristotelian Thomist thought and natural law theory. He has taught at several universities, including the University of Notre Dame (USA), The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (Poland), the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross (Rome), and the LUMSA (Libera Università Maria Ss. Assunta, Italy). He has more than 200 publications, including articles, editorials, books chapters, edited books, and translations.

****

From The Pandemic To This Book

Since the pandemic began, I have resigned myself like everyone else to everything we all had to resign ourselves to. The first lockdown, the second lockdown, curfews, masks, hand sanitizers, work and family difficulties, the rules for going to Mass and to the supermarket, the abolition of travel and holidays, the new waves, the hopes for vaccines that, perhaps, would save us; and, again, the economic crisis, the monopolization of existential and mass media news, focused every day on the bulletin of deaths and infections, on new outbreaks, on new yellow or red areas, on the latest rules to follow, on the reactions of individual states, but also on some new TV show personalities, especially virologists and epidemiologists or those presumed to be such.

I’ve become familiar with things that I almost didn’t know existed before, at least from an existential point of view, but which have forcefully entered my daily sources of interest and information. Things like drug agencies, the World Health Organization, their protocols and conflicts of interest, emergency approval procedures, journals, and university departments of medicine. I reluctantly agreed to read and discuss all these things every day in social networks. I have also lived through new experiences of which I have a positive or still uncertain balance.

My young children have had contact with their parents that few children have ever had in our busy world. My baby girl was born just before the first lockdown. Thank God, we had just managed to repair the house from serious mold problems and to return there between the end of January and February 2020. I and my wife, who is also a lawyer and scholar passionate about culture and everything else, had never imagined spending such long periods of monastic isolation, work, and intimacy.

We too, at home, have had our waves and regulatory changes. There was that of pizza and homemade desserts. There was that of sports played with children on the terrace (also to work off sweets and pizza). There was that of the camping on the terrace, where we set up a large family tent on an artificial lawn for Christmas 2020, surrounded by solar-powered Christmas lights (the holiday budget was spent in 2020, and with better results, in this way). There was that of the giant terrace nativity scene, with water pump and waterfalls and real ornamental plants, built at home with the children by carving and painting polystyrene and wooden boards for the stable. There have been attempts at homeschooling, also with the help of heroic grandparents who have come over as much as possible, despite the curfews and occasional swab tests, also to allow us to isolate ourselves from time to time in a room to get some work done. There have been such beautiful and genuine family experiences that, at times, with my wife, we even were thankful for the pandemic, roughly with that spirit with which, in the Easter Mass, since St. Augustine, we refer to original sin in terms of felix culpa.

Smart working and the development of new online work options are certainly among the positive aspects of the epidemic. Today we have learned more about how many things can be done remotely with the technologies we have available. Smart or remote working allows many people, in many ways, to better reconcile their professional life with their personal and family life. Let’s hope there is no turning back in this area, after the emergency is over.

I think back on all this, not without ardor, to say that, even in the worst moments of the pandemic, I had never thought of making a professional effort to talk about it. Even when, taking seriously some of my wife’s perplexities, I had a second thought about vaccines and government policies, and when I began to study relevant sources of information with greater professional attention and to listen to online lectures and specialized conferences on the subject, I didn’t think even for a moment of writing a book about it. Even when the witch hunt against the so-called anti-vaxxers began, when the mass media and politics started to treat me, my wife, and many of our friends and colleagues who had doubts about vaccines and about the decisions to be made about them as if we were fools and idiots to mock and publicly insult…. Even in this predicament I didn’t think about writing a book on the subject. In fact, my initial reaction was the opposite. I decided to stop reading many newspapers or watching television and instead to concentrate on other books I was writing. Unfortunately, hateful excerpts of pseudo-journalistic talk shows conducted in the name of ignorance, arrogance and insult still tormented me through the clips that inevitably populated social media. Still, not even this additional pressure incited me to the point of turning everything I had studied and found out about the pandemic into a book. Posting some occasional ironic, outraged, or staggered comments on social media was enough to distract me so I could let it out and go back to my regular work.

There was one thing that broke the camel’s back, though, and it was not about my professional life but about my life of faith. Political institutions had breached their fundamental duty to respect the truth and freedom of their citizens. They violated the right of every free person to receive correct and honest information. They had tried demagogically to bend and control people’s will, intelligence, and conduct. Physicians, after the first wave of heroism, so charged with magnanimity and exemplarity, had finally allowed themselves to be harnessed and standardized downwards by a political power that wanted them to be bureaucrats who stayed far away from patients, at least until hospitalizations. They had allowed themselves to be replaced by sloppy and generic directives from impersonal government agencies, reduced to paper pushing, thus mortifying the exercise of a profession that always begins and ends with care and attention for the patient. Scientists had also failed by letting a generic, magical, and mystical reference to a higher and nonexistent entity called “Science” take the place—in the common feeling and in the demagogy of ignorant and unscrupulous politicians and journalists—of serious and real discussion among scholars and of critical thinking. Journalism had died, replaced by the will to power of those who have the media in their hands and decide to use the media only and exclusively to convince everyone of their prejudices and to make the masses conform to the decisions of the political class. But shouldn’t journalism be the bulwark of investigation and real democracy precisely in times when politics risks having too much free rein and too much power?

Yet, despite everything, despite all these failures, it was still enough for me to turn off the TV, close the online pages of the new regime’s newspapers, and concentrate on my family, my research, and my books.

One thing, as I said, finally stopped me from simply closing the door and staying at home doing my own thing: the failure of the church. I am referring, of course, not to the true Church, that is, to the Mystical Body of Christ, which lives in the mystery of His People, and which walks in history assisted by the Spirit of Truth. The true Church is the humanity of Christ, God incarnate who becomes a sacrament, who becomes the mystery of God’s presence among us. When God becomes man, matter becomes direct contact with the supernatural: “Philip said to him, “Master, show us the Father, and that will be enough for us.” Jesus said to him, “Have I been with you for so long a time and you still do not know me, Philip? Whoever has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, ‘Show us the Father’?” (John 14: 9-10).

The Incarnation does not end with the ascension of Jesus into Heaven. The Incarnation remains until the end of time. It’s just that, after the Ascension, the sacramental mystery doubles. While two thousand years ago, we saw Jesus and, by touching His humanity, we really and mysteriously touched God, now we don’t see Him, but we really and mysteriously touch God by touching His sacramental humanity, which is truly present in His People. Whoever does not understand that the Church is the Body of Christ incarnate which continues to walk and act mysteriously in history with the legs and arms of His faithful has not understood anything significant about the Church. This Church, for a believer, can never fail. Men, however, are fallible and sinful. Even the righteous sins seven times a day, which is an important warning against any presumption and idolatry of personalities. Here on earth, no one is holy, and we all must always be very careful. Only the People of God as a whole are Holy, because they are the Body of Christ.

The church as a human institution is made up of men who are all fallible, starting with the Pope (except of course for those very rare times in history in which he speaks ex cathedra on matters of faith and morals). The Church as a militant People (that is, without considering those in Purgatory and Paradise) is made up of three types of faithful, all called to be saints in the same way and all cells of the Mystical Body of Christ: there are clerics (deacons, priests, and bishops), there are the religious (who make vows and who could also be clerics at the same time), and there are the lay faithful. Nobody is in the big-league team, and nobody is in little, or very little, leagues. The dignity of every believer is rooted in the call to communion with God and in letting Christ work in him to impact the history of the world. Clerics have an institutional responsibility, but if some or many clerics make a mistake, Christ will work more through other faithful, because the true, sacramental Church is never in the hands of any single person or group of mere men.

When I talk about the failure of the church in these times of pandemic, I am therefore referring to the failure of many clerics (not all, thank God), who should be talking about the saving message of the Gospel and the truths revealed by God and who instead talk about vaccines and of the green pass as if these things belonged to the depositum fidei. I speak of the failure of a church that generates ethical doubts about things that belong to the conscience and prudential reasoning of every faithful individual. I am speaking of a church that aligns and allies itself with political or economic power, mistaking its supernatural ministry for assistance to the dubious or questionable policies of the rulers of the moment. I speak of a church that remains silent in the face of demagogy and disinformation. I speak of a church indifferent to the persecution of so many righteous. I am speaking of a church that discriminates and generates conflicts among its own faithful for the benefit of the transitional policies of utilitarian rulers. I’m talking about a church that has turned its priorities and value hierarchies upside-down. Where are the atheists and anti-Catholics, who always scream at alleged medieval obscurantism, in these days when spiritual power and temporal power seem to inexplicably walk hand in hand?

When the “churchmen” praise politicians too much or rejoice too much in their attention or seek them too much or manifest too many inferiority complexes with respect to political institutions or no longer know how to distinguish the freedoms of the Church from the freedoms of politics, I become particularly worried. Clerics are no more intelligent than the lay faithful. It is often the other way around. And this is the reason why they make themselves so often ridiculous with the politicians and the powerful on duty. Many clerics have an inferiority complex because they do not feel equal to the world. Economics, politics, and science are too high for them, too unreachable, and, without realizing it, they end up kneeling facing the wrong way, no longer in the direction of the Altar. We lay people do not have these problems. We are the politicians, the scientists, and the economists. We cannot have any inferiority complex towards ourselves. And I am convinced that it is also for this reason that, in times like the present ones, in which the church of clerics is the victim of its own inferiority complexes and generates too much confusion and division among the faithful, the Mystical Body tends to inspire the laity more to the responsibility of distinguishing the boundaries of the depositum fidei, on the one hand, and of what belongs to Caesar, on the other.

The straw that broke the camel’s back, and that led me to this book, was hearing the greatest religious authority in the world say that getting vaccinated is an act of love, thus providing an assist to the political authorities who sought to proclaim that vaccination is a civic duty. At this point, the poor faithful Catholic who has doubts about the vaccine, and that he is also a good citizen, is surrounded. Is his doubt then an act of selfishness? Is it a temptation from the devil? Is it an act contrary to the common good? In addition to his own religious and political authority, he is at the same time discriminated against and persecuted by all with the complicity of the mainstream media. He has become the villain to be ridiculed as the selfish enemy of the common good, with the blessing of the Pope and the Presidents. All this is unacceptable and, in my own little way, it required me to at least put my professional skills to use in the service of the persecuted righteous.

Featured image: “Lucifer devouring Judas Iscariot, Brutus and Cassio.” Opere de Dante. Woodcut printed by Bernardino Stagnino, ca.1512.