The Crusades have long been a contentious topic, and over the years scholarship has largely fallen into two camps: those that view this enterprise as European aggression (Ur-colonialism) and those that view it as a response to relentless Muslim aggression. The former view tends to predominate, especially in popular culture, where films, television shows and novels favor the trendy explanation of the Levant falling victim to “European violence.” Given the wide reach of media, such simplistic views have become “settled history.” Various efforts are made to counter this ideological reading of the Crusades (and the Middle Ages in general), but with little effect. The mainstream narrative yet holds sway, and in the popular mind the Crusades are evidence of innate European belligerence unleashed upon the world. One of the major problems with this narrative approach is Presentism, which then poses the “East” and the “West” as two irreconcilable monoliths that can only but continually clash. Saner scholarship recognizes the silliness of such an approach and has slowly been trying to make a difference by showing that the medieval world was neither ignorant nor parochial, and in which violence was more controlled than in our own day. The most recent example of such scholarship is Helena P. Schrader’s latest book, The Holy Land in the Era of the Crusades: Kingdoms at the Crossroads of Civilization, 1100-1300.

This eloquent book is a comprehensive narrative history of a unique Christian civilization in Palestine—the Crusader States. It is also a noble and honest effort to “set the record straight,” by presenting the entirety of the crusading effort as one of interaction, in which the East and the West met and fashioned a unique civilization. In the words of Schrader:

“While historians of past centuries portrayed the Latin Christians living in these states as a tiny, urban elite afraid to venture into the countryside out of fear of their subjects, there is a growing consensus among the scholars of the twenty-first century that the majority of the population was Christian, not Muslim, and that the degree of intermingling and tolerance between Latin and Orthodox Christians was much higher than had been assumed” (xxxiv).

Towards this end, the book seeks to be as meticulous and well-researched as possible, in which it aptly succeeds. It begins with a 24-page chronology that details the history of the Levant within the context of Christianity (which brought Catholics, commonly known as the “Franks” or “Latins,” into the region, who then established various principalities, or “Crusader States,” which were politically linked with each other and with Europe) and Islam (which eventually gave the Turks enduring dominance in the Holy Land).

The book is divided into two parts, wherewith the analysis moves from the larger to the particular. Thus, Part I, “A Short History of the Crusader States,” describes the process through which the Franks came to the Levant and set up religious, political, cultural and military structures which would ensure that the Holy Land would remain territory essential and important to the Christian faith. This meant the establishment of permanent settlements, or what later became known as the “Crusader States,” or “Outremer” (“Overseas”), as the people of that time called this settlement. Schrader carefully traces the course that needed to be followed to ensure success in this undertaking, and as such follows the rise and fall of the Crusader States, from 1099 (when Jerusalem came under Frankish rule) to 1291 when Acre fell and Frankish influence contracted and eventually disappeared from the region.

The importance of Part I is that it gives the reader a thorough understanding of the complexity of the Crusades in their entirety, while never neglecting the dynamics at play in the Muslim world, where Mongol, Turk and Egyptian rivalries held sway. It is truly commendable that Schrader offers an all-inclusive review of the forces in contention in the Levant over a two-hundred-year period. What emerges is the real picture of the Crusades—that they were a massive investment of effort, talent, money and most of all of faith which allowed for a unique civilization to emerge and flourish, becoming an envy of the world in so many ways.

It is the quality and quantity of this “Crusader” or “Frankish” civilization that Schrader turns to in Part II of her book, which is sub-titled, “A Description of the Crusader States.” Here, Schrader really comes into her own as she takes the reader on a captivating “journey” into the world of Outremer. Each chapter presents facts and analysis, so that a lot of the popular myths about the Crusades are laid to rest. For example, we learn that the population of the Levant was predominantly Christian and not Muslim, as widely and mistakenly assumed. Indeed, the Christian population of what is now known as the Middle East and even Central Asia was heavily Christian. It was only in the fourteenth century that the Christians of the East were methodically annihilated, and the area became what it is today—the final chapter of this annihilation was the Armenian Genocide (which occurred in two parts: 1890-1909 and 1915-1917). Of course, this topic lies outside the scope of Schrader’s book.

Next, Schrader examines the complex polity that emerged in Outremer, the concept of the “nation-state,” which of course had a direct influence on the life of the West in the centuries ahead, down to our own time, where the nation-state is the prime form of civilization. In other words, Outremer was a two-hundred-year long success story—it was hardly colonial “occupation.” The reason for this success, as Schrader shows, is the stability of the institutions that were rather quickly established, such as the very effective judiciary, in which the Muslim peasantry prospered (unlike Muslim peasantry in Islamic-run jurisdictions), as well as the establishment of churches and monasteries which allowed culture, learning and the Christian faith to flourish, especially the ease of pilgrimage (which led to the rise of Holy Land “tourism,” and all of the support industries that tourists need).

Diplomacy was another key component of the success of Outremer, whereby a balance of power was effectively achieved and maintained between the various rivals, namely, Mamluk Egypt, the debilitated Byzantine rule, the many fiefdoms of the Turks, and the Mongol Empire. It was the Crusader States who “micro-managed” this balancing act, so that trade between the East and the West flourished, despite the ambitions of particular rulers: “The willingness… to treat with the religious and strategic enemy on a short-term tactical basis meant that de facto peace reigned in the crusader states far more frequently than war” (193) , because “the Franks maintained sophisticated and largely effective diplomatic relations with all the major players in the Eastern Mediterranean” (196).

As Schrader also points out, the Levant was a backwater before the Crusaders came—but because the land was holy to Christianity, it saw a massive input that transformed the region into a going concern: “Investment into infrastructure revitalised the rural economy and enabled the expansion of trading networks. Existing cities grew, and ancient cities such as Caesarea and Ramla, which had gone to ruin, were revived. Indeed, entire new settlements and villages were built. The larger cities, such as Acre, Tyre, Beirut, Tripoli and Antioch, became booming urban centres with larger populations than the capitals of the West. Not until the mid-thirteenth century did Western European cities start to compete in size with the cities of the Latin East” (197).

As well, this investment returned strategic importance: “Most importantly, the Franks connected the traditional oriental trade routes with the growing, increasingly prosperous and luxury-hungry markets of Western Europe” (198). The reason for this flourishing trade was the building of infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, and water management. Trade agreements were struck and banking practices introduced, which then led to manufacturing. Sugar, textiles (especially silk, samite and siqlatin), soap, wine, olive oil, leather goods, glass were all manufactured in the Crusader States.

Given this revitalization program, agriculture returned to this land long considered barren, so that cities began to flourish, and a distinct Outremer culture emerged, such as icon painting, book production, shrines and holy places where the faithful came in droves to receive blessing in the land trodden by God Himself, as the famous 13th century Palestinalied (Song of Palestine) relates: “Ich bin komen an die stat,/ dâ got menischlîchen trat (I am come to the city where God trod as a man).” This spiritual “currency” lay at the heart of this region, a “currency” that could never be depleted. And here the work of charity was paramount, which saw the building of hospitals, caravanserais, inns, as well as monasteries, churches and many chapels by confraternities and monastic orders.

The cities themselves were well-planned, with effective sewage systems, baths and even flushing toilets. Trade supplied the many open-air and enclosed markets. There were orchards and gardens surrounding each city, with aqueducts, pools and fountains to supply water. It is important to note that many of these cities were not fortified—that is, they did not lie inside protective walls—cities such as Nazareth, Hebron, Nablus and Ramla. This detail is important—for it points to the fact that life was, in fact, very peaceful, which flies in the face of the usual and popular trope of Crusader brutality.

But this not to say that the military aspect was not important, for defense was necessary, given the endless ambitions of the rulers of the time (Mongol, Mamluk and Turk). Thus, Frankish Levant saw the emergence of unique castle styles, chief and most impressive of which was the concentric castle, the best examples of which is Krak de Chevaliers and Belvoir which overlooks the Jordan valley (“Belvoir” in Old French means, “Good view”).

Frankish architecture was unique also because it did not destroy what originally existed: “Beyond their sheer scale and number, one of the most striking features of these various projects was the degree to which the Franks sensitively and respectfully incorporated the remains of earlier buildings into their renovation projects. In sharp contrast to the prevailing view of crusaders as bigoted barbarians, when it came to architecture, the crusaders sought to preserve rather than destroy. This was true of Muslim structures as well as Christian ones” (233).

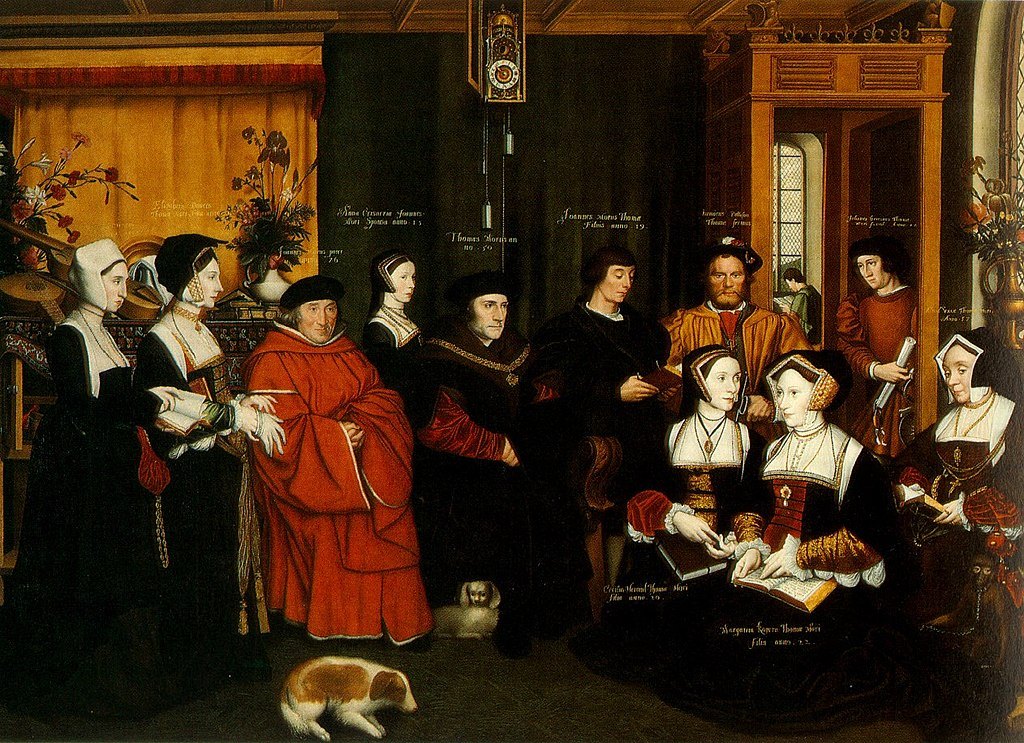

One of the greatest achievements of Outremer was its art and its literature, both little known and studied. There survives, for example, the exquisite Melisende Psalter, with its illustrations that perfectly combine Byzantine, Armenian, Syriac, Coptic and Latin elements to produce a style that is original to Outremer. And then there are the frescoes of the 12th century Church of St. Jeremiah at Abu-Ghosh (the biblical Emmaus), which are the finest expression of Crusader art (despite their Byzantine “look”), although they now survive in a much damaged condition.

This comprehensive book ends with the history of the Ibelin family who typify the kinds of people that came to Outremer and made it the splendorous civilization that it was: “…while the Ibelins were undoubtedly exceptionally successful, they were also in many ways typical. They embodied the overall experience, characteristics and ethos of the Franks in the Holy Land. They came from obscure, probably non-noble origins, and the dynasty’s founder can be classed as an ‘adventurer’ and ‘crusader’. They rapidly put down roots in the Near East, intermarrying with native Christian and Byzantine elites. They were hardened and cunning fighting men able to deploy arms and tactics unknown to the West and intellectuals who could win wars with words in the courts. They were multilingual, cosmopolitan and luxury-loving, as comfortable in baths as in battles” (267).

But why did this great civilization in the Holy Land end, after two hundred years of great success? The answers are as varied as the scholars who seek to give a response to this question. Schrader is accurate in her own conclusion—that Outremer was a victim of its own success. Because it was such a “shining city on the hill,” others fought to possess it. But more tragically, the bane of Frankish rule was the incessant in-fighting, where factions vied for power and where loyalty was circumscribed by personal ambition. As well, the latter rulers had divided loyalty—they were more interested in maintaining their holdings and influence in Europe than looking after what previous generations had built in the Holy Land. It is that old cycle of civilization—the generations that inherent wealth effectively waste it and lose it.

And the legacy of Outremer? This is how Schrader summarizes it: “… the crusader states in the Levant were the home to a rare flourishing of international trade, intellectual and technological exchange, innovation, hybrid art forms and unique architecture, advances in health care and evolution of the constitutional principles of the rule-of-law” (305).

For its scope, its depth and its variety of subject matter, this book truly succeeds as a work of exceptional narrative history. By glancing at the past, we may well learn something about the narrowness of our own age.

C.B. Forde confesses to being a closet history buff, that is whenever he can tear himself away from the demands of the little bit of land that he cultivates.

Featured: The Last Judgment, a fresco in the Church of St. Jeremiah (Emmaus), in Abu-Ghosh, Israel; painted in the latter parts of the 12th century.